78 Thoracic Trauma

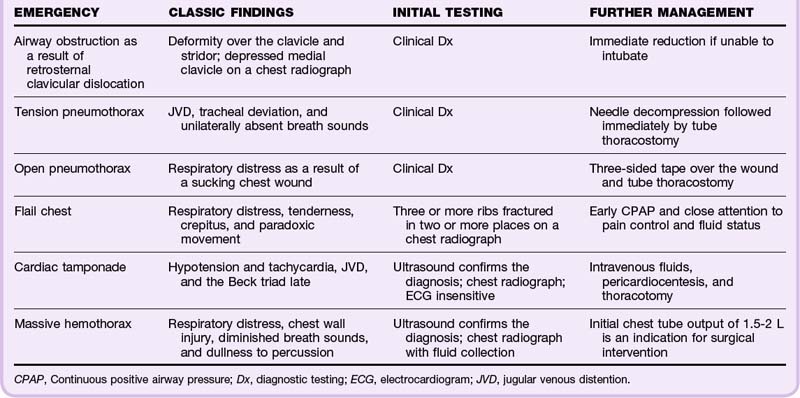

• Emergency life-threatening conditions that need to be detected during the primary survey include airway obstruction, tension pneumothorax, open pneumothorax, massive hemothorax, flail chest, and pericardial tamponade (Table 78.1).

• Urgent life-threatening conditions to detect during the secondary survey include simple pneumothorax, hemothorax, pulmonary contusion, tracheobronchial injury, blunt cardiac injury, traumatic aortic injury, diaphragmatic injury, and esophageal injury.

• Common thoracic cage injuries are not always associated with serious injury, but some individuals, especially pediatric and elderly patients, may require admission for associated injuries and respiratory therapy.

Epidemiology

Head and thoracic injuries from moving vehicle collisions (MVCs) and firearms account for the majority of the more than 160,000 injury-related deaths in the United States each year. Most fatalities occur immediately as a result of massive cardiac or vascular injury. Rib fractures are the most common thoracic cage injury following blunt thoracic trauma. Isolated first and second rib, sternum, and scapula fractures are no longer considered markers of traumatic aortic injury.1 However, rib fractures must still be considered markers of significant injury. Most patients seen in trauma centers with rib fractures will have hemothorax, pneumothorax, or a pulmonary contusion. Three or more rib fractures at any anatomic site dramatically increases the risk for spleen and liver injury. Likewise, scapula fractures are uncommon yet signify a high-energy mechanism of injury, almost always with important associated injuries.

Seat belts have increased the incidence of sternum fractures while reducing the number of lives lost in MVCs. Isolated nondisplaced sternum fractures are no longer considered markers of blunt cardiac injury.2 More complicated fracture patterns predict associated injuries. Fractures of the manubrium, manubrium-sternum synchondrosis, and proximal part of the sternum and severely displaced sternum fractures are associated with an increased incidence of spinal fractures. Displaced fractures of the body of the sternum are associated with a higher incidence of intrapulmonary and cardiac injuries.3

Thoracic Cage Injuries: Rib, Sternum, and Scapula Fractures

All thoracic cage injuries result in significant pain, splinting, atelectasis, and increased risk for pneumonia. Multiple rib fractures interfere directly with the mechanics of ventilation. Fracture fragments may penetrate the pleura and lungs and result in pneumothorax and hemothorax. Traditionally, fractures of the 6th to 12th rib on the right suggest liver injury and on the left suggest splenic injury. However, any fracture, especially multiple fractures, increases the risk for liver and splenic injuries.4

Because children have more elastic chest walls, more energy is transmitted to the underlying lung, and greater force is required for fractures. Excluding other major trauma, 71% of rib fractures in children younger than 2 years result from abuse.5

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Sternum fractures are best detected on the lateral chest radiograph. Associated rib fractures and mediastinal abnormalities may be evident on the PA view. In experienced hands, bedside ultrasound may be more sensitive than radiographs for detection of both rib and sternum fractures, as well as associated hemothorax or pneumothorax.6,7 The electrocardiogram (ECG) should be examined for evidence of cardiac injury. Scapula fractures are often missed on the initial chest radiograph unless the scapular outline is specifically inspected. Shoulder radiographs can confirm suspected fractures (Fig. 78.1).

Helical computed tomographic (CT) angiography should be performed on hemodynamically stable patients when clinically significant underlying injury is suspected. An abdominal CT scan can rule out intraabdominal injury in patients with tenderness or fracture of the sixth rib or below, three or more rib fractures, hypotension noted in the field or emergency department (ED), abdominal or flank tenderness, pelvic or femoral fractures, or gross hematuria.8

Flail Chest

Flail chest occurs when three or more ribs are fractured in two or more places and a discontinuous segment of the thoracic wall is produced and moves paradoxically with respiration. Flail chest is diagnosed in approximately 5% of thoracic trauma patients seen in level I trauma centers, typically in the setting of multisystem trauma. Mechanisms include MVCs, crush injuries, assault, falls, and even minimal trauma in elderly patients. Respiratory insufficiency results primarily from the underlying pulmonary contusion. Pneumothorax occurs in 50% of cases and pulmonary contusion in 75%.9

Treatment

Immediate chest tube placement is required for assessment and management of other injuries, including pneumothorax and hemothorax. Continuous positive airway pressure is the first-line treatment in awake and cooperative patients with worsening oxygenation or ventilation.10 Criteria for intubation include airway obstruction, respiratory distress, shock, closed head injury, and need for surgery. Endotracheal intubation should be performed only when necessary to avoid the increased mortality associated with nosocomial pneumonia.

Fluid replacement should be managed carefully to avoid overhydration and worsening of lung injury. Analgesia is titrated so that patients are more willing to make sufficient inspiratory effort, but excessive sedation should be avoided. Intercostal nerve blocks, epidural anesthesia, or even surgical fixation of the flail segment may be beneficial.11 Stabilization of the flail segment in the ED or prehospital setting has not been shown to be helpful, and aggressive stabilizing efforts impede overall thoracic mechanics.

Pneumothorax and Hemothorax

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Patients with a simple pneumothorax classically have chest pain, diminished breath sounds, crepitus, hyperresonance, and mild to moderate respiratory distress. Patients with tension pneumothorax are classically seen in extremis and exhibit jugular venous distention, tracheal deviation, unilaterally absent breath sounds, or tachycardia followed by hypotension immediately before death (or any combination thereof).12 Patients with open pneumothorax have chest wall wounds that produce sonorous sounds and are in severe respiratory distress. Typical symptoms of hemothorax are respiratory distress, chest pain, and diminished breath sounds with dullness to percussion.

Atypical manifestations are more common than classic ones. Respiratory distress may occur as a result of multiple other causes. Patients can have severe pain from distracting injuries. Breath sounds may be difficult to hear in a noisy environment. Physical examination in patients with penetrating thoracic trauma is unreliable for the detection of pneumothorax or hemothorax.13 Patients with simple pneumothorax may be minimally symptomatic or may be cyanotic and in severe respiratory distress. Tension pneumothorax most commonly occurs in intubated patients as a result of positive pressure ventilation, sometimes after overzealous bagging.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

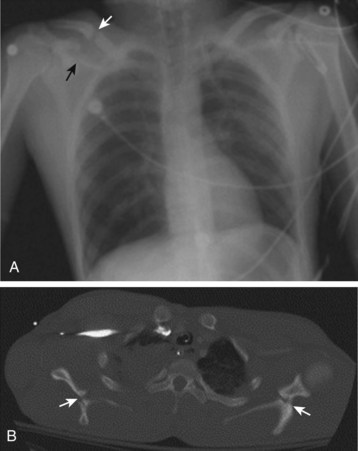

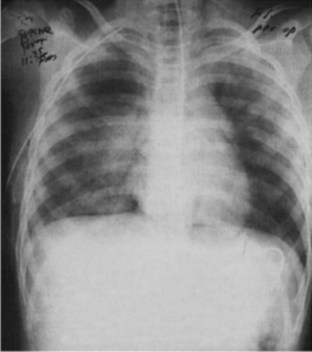

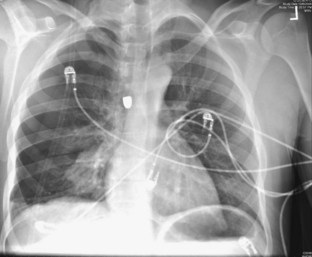

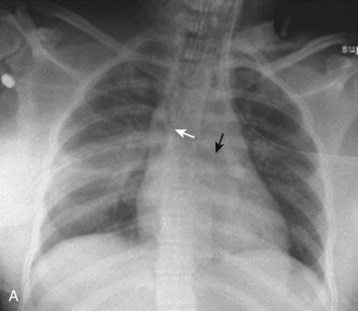

In an upright patient, a hemothorax appears as a fluid layer in the affected hemithorax. Early collections are noted to blunt the costophrenic angles on the AP and lateral radiographic views. Hemothorax often appears as only a diffuse hazy infiltrate in a supine trauma patient. Hemopneumothorax has a fluid layer with a flat superior border, in contrast to the round meniscus of an isolated hemothorax (Figs. 78.2 and 78.3). Decubitus views better demonstrate a small hemothorax.

Fig. 78.2 Chest radiograph showing obvious left-sided tension pneumothorax with mediastinal shift.

(From Ullman EA, Donley LP, Brady WJ. Pulmonary trauma emergency department evaluation and management. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2003;21:291-313.)

Fig. 78.3 Chest radiograph showing right hemopneumothorax along with a bullet.

(Image courtesy Dave Andreski, MD.)

An extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) scan can diagnose pneumothorax and hemothorax with higher sensitivity than portable chest radiography can in experienced hands. An extended FAST scan is especially helpful when chest radiography is not immediately available and in mass casualty situations.14

Treatment

Tension pneumothorax and open pneumothorax are both clinical diagnoses that require immediate treatment with needle thoracostomy followed by tube thoracostomy, even when based on clinical evaluation, before radiographic confirmation. All suspicious open chest wounds should be covered with petrolatum gauze secured on three sides to prevent the entry of air during inspiration and allow the exit of air during expiration. Postprocedure radiographs should be obtained to confirm placement, drainage of air and blood, and reexpansion of lung. Prophylactic antibiotics with chest tube insertion do not reduce the risk for empyema or pneumonia.15

Follow-up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Occult traumatic pneumothorax detected on a CT scan requires only close observation for respiratory distress, progression, and the development of complications. Tube thoracostomy must be immediately available but is not required even with positive pressure ventilation.16 Any prolonged surgery, diagnostic testing, or transport preventing immediate tube thoracostomy requires prophylactic placement.

In patients with penetrating injuries and a negative initial chest radiograph, upright PA and lateral chest radiographs should be repeated in 3 to 4 hours.17 Patients with normal findings on repeated radiographs and no significant associated injuries are discharged with wound care and follow-up instructions. Patients with asymptomatic blunt chest trauma and normal findings on the initial chest radiographs do not require repeated films before discharge. All patients with chest tubes are admitted to the trauma, cardiothoracic, or general surgery service in the care of personnel experienced in managing chest tube equipment.

Pulmonary Contusion

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The patchy or diffuse air space opacification above the site of injury with pulmonary contusion is often present on the initial chest radiograph and typically progresses over the first 6 hours (Fig. 78.4). Initial CT scanning is more sensitive than chest radiography but seldom changes the initial management of pulmonary contusion. Pulse oximetry is essential to detect early clinical deterioration.

Follow-up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Patients with pulmonary contusion require admission to the intensive care unit for oxygen administration, chest physical therapy, incentive spirometry, suctioning, analgesia, and close monitoring. Overhydration must be avoided to prevent iatrogenic worsening of capillary leak and lung function. Prophylactic steroids and antibiotics are not recommended.18 Isolated pulmonary contusions typically resolve within 14 days without long-term complications. Disability and mortality rates are higher in patients with larger areas of contusion, flail chest, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and pneumonia.

Tracheobronchial Injury

Blunt injuries to the thoracic trachea are typically caused by high-energy MVCs, crush injuries, and falls. Rapid deceleration produces a shearing force with injury typically within 2 cm of the fixed carina. Injuries to the esophagus and spine are the most common associated injuries. Head, vascular, nerve, and intrathoracic injuries also occur frequently with both blunt and penetrating tracheobronchial injuries (Box 78.1).

Box 78.1 Approach to Thoracic Trauma*

Blunt Trauma

High-energy mechanisms: Falls greater than 3 m or motor vehicle collisions at more than 30 mph

All injuries: CXR and pulse oximetry. If pneumothorax or hemothorax, insert a chest tube

Traumatic aortic injury: A mechanism with chest wall tenderness or abnormal CXR evidence requires helical CT angiography; if negative, evaluate for traumatic aortic injury; if findings indeterminate, obtain an aortogram; if positive, transfer the patient to the operating room

Blunt cardiac injury: With abnormal ECG, hypotension, or dysrhythmia, cardiac monitoring and hospitalization for 24 hours with repeated ECGs every 8 hours; with hypotension or symptomatic dysrhythmia, formal echocardiography

Penetrating Injuries

All injuries: Continuous pulse oximetry and PA and lateral CXR at 0 and 6 hours

Anterior cardiac box: FAST examination to evaluate for pericardial fluid

Posterior box and transmediastinal gunshot wounds: Angiography for great-vessel injury; with signs and symptoms of injury, esophagography or esophagoscopy and bronchoscopy

Posterior box stab wounds: If abnormal mediastinum on CXR, angiography for great-vessel injury; with signs and symptoms of injury, esophagography or esophagoscopy and bronchoscopy

Thoracoabdominal: DPL with a red blood cell count of 10,000 cells/µL, laparoscopy/thoracoscopy or laparotomy to evaluate for diaphragmatic injury

Treatment

During orotracheal intubation, a smaller-size endotracheal tube should be inserted and placed past the injury if possible. To prevent worsening of the injury, force should be avoided during placement of the endotracheal tube. When orotracheal intubation is not possible, the endotracheal tube should be placed through the anterior neck wound into the trachea. The EP must be careful to avoid pushing a transected trachea deeper into the thorax. In patients with complete transection and retraction of the trachea, major intervention is required. A right-sided thoracotomy should be performed (to avoid the aortic arch on the left), and the EP should attempt to visualize the injured trachea, support it, and establish an airway. Extension to a left-sided thoracotomy may be needed for complex distal injuries.19 Tube thoracostomy is required, often with multiple tubes to drain the resulting pneumothorax and reexpand the affected lung.

Blunt Cardiac Injury

Cardiac concussion, or commotio cordis, occurs when a blow to the chest briefly “stuns” the heart; it results in dysrhythmia, hypotension, syncope, and often sudden death but without permanent cellular damage. Commotio cordis may result from an anterior chest wall impact at a moment when the myocardium is refractory to depolarization and can result in fatal arrhythmia, also known as the R-on-T phenomenon.20

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Blunt cardiac injury typically occurs in patients with multiple blunt trauma injuries. Patients with commotio cordis generally experience immediate dysrhythmia and loss of consciousness. Though usually fatal, the survival rate is increasing as a result of increased public awareness, immediate cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and increased availability of automatic external defibrillators.21

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

An ECG should be recorded in all patients with suspected blunt cardiac injury. Traditionally, stable patients with normal results on the initial ECG were considered to be at low risk for complications and safe for discharge. However, more recent literature suggests that patents may still be at risk for complications of blunt cardiac injury, including lethal dysrhythmias up to 12 hours after trauma and non–life-threatening dysrhythmias up to 72 hours later.22 New findings on the ECG suggestive of myocardial contusion include unexplained tachycardia, ST- and T-wave changes, conduction abnormalities, and dysrhythmias.

Evaluation of cardiac markers is not routinely indicated in patients with blunt cardiac injury. The exception is serial troponin I measurement in patients with an ischemic pattern on the initial ECG and in patients in whom cardiac ischemia may have precipitated the trauma. However, a recent metaanalysis supports the use of troponin I as a sensitive test for myocardial contusion when determined at admission and 4 to 6 hours later.23

Penetrating Cardiac Injury, Cardiac Tamponade, and Emergency Department Thoracotomy

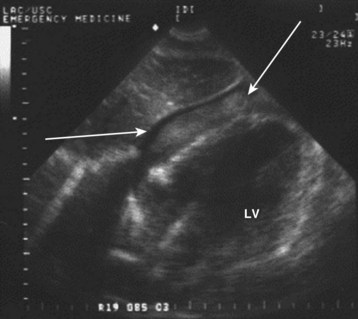

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

An ultrasonographic subxiphoid view (Fig. 78.5) may detect pericardial fluid in patients with suspected cardiac injury. Pericardial fluid with diastolic collapse of the right atrium and ventricle is diagnostic of pericardial tamponade. Any pericardial effusion in unstable trauma patients with equal bilateral breath sounds signals tamponade requiring immediate operative intervention. Although the sensitivity of FAST scans approaches 100% for hemopericardium, false-negative results may occur when blood drains rapidly into the thorax. The possibility should be considered in patients with small anterior stab wounds and persistent left hemothorax despite tube thoracostomy.24

Treatment

Thoracotomy is reserved for patients with cardiac tamponade who are in cardiac arrest or impending arrest. The likelihood of functional survival after ED thoracotomy is greatest for victims of stab wounds with isolated cardiac injury who have signs of life on ED arrival. At the trauma center, thoracotomy is performed on victims of penetrating trauma who experienced cardiac arrest in the ED or within 10 minutes of arrival at the ED and on blunt trauma patients who experienced cardiac arrest in the ED. In the ED without surgical support, thoracotomy is best performed by a skilled EP only on patients with thoracic stab wounds or isolated gunshot wounds who lost signs of life in the ED or within 10 minutes of arrival in the ED. In all other cases, ED thoracotomy should be performed only if a qualified surgeon is present or immediately available (Table 78.2).25–28

| SETTING | PENETRATING INJURIES | BLUNT TRAUMA |

|---|---|---|

| Trauma center | Cardiac arrest in the ED or within 10 min of ED arrival | Cardiac arrest in the ED |

| Community ED without emergency surgical backup | Patients with thoracic stab wounds or isolated gunshot wounds who lose signs of life in the ED or within 10 min of ED arrival | All other ED thoracotomies should be performed only when a surgeon is available within 10 min |

ED, Emergency department.

Great Vessel Injury

Great vessel injury is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality with both blunt and penetrating thoracic trauma. Traumatic aortic injury is the second most common cause of blunt traumatic death. Eighty percent of victims of traumatic aortic injury die immediately. The majority of survivors can be saved with prompt ED diagnosis, blood pressure control, and operative repair. Five percent of patients will be unstable on arrival and have a mortality rate of up to 98%. The remaining 15% will be hemodynamically stable, which often contributes to a delay in diagnosis and a mortality rate as high as 25%.29

The descending aorta is fixed within the thorax by the ligamentum arteriosum and the intercostal arteries. Sudden deceleration causes the aortic arch to swing forward and produces a shearing force with resultant injury just distal to the takeoff of the left subclavian artery. Traditionally, traumatic aortic injuries have been considered only in patients with “major mechanisms of injury,” including high-speed MVCs with frontal or side impact and motorcycle crashes. However, the injury has been reported with less impressive mechanisms such as pedestrian-versus-auto collisions, falls, and crush injuries. Use of restraint systems does not protect persons from traumatic aortic injuries.30,31 Penetrating injuries to the great vessels typically result from both gunshot penetration and stabbing.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

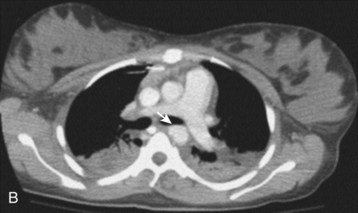

The initial chest radiograph should show evidence of traumatic aortic injury (Fig. 78.6, A). The most sensitive criterion is mediastinal widening, usually larger than 8 cm on an AP view; however, a subjective interpretation of mediastinal widening is more reliable. Other mediastinal abnormalities suggesting mediastinal hematoma secondary to traumatic aortic injury are an obscured aortic knob, loss of the AP window, a displaced nasogastric tube, widened paratracheal stripe, widened paraspinal interface, depression of the left mainstem bronchus, left hemothorax, left apical pleural cap, deviation of the trachea to the right, and multiple rib fractures. The more abnormalities seen on the chest radiograph, the higher the sensitivity in identifying an aortic injury. A normal chest radiograph, however, does not rule out a traumatic aortic injury.

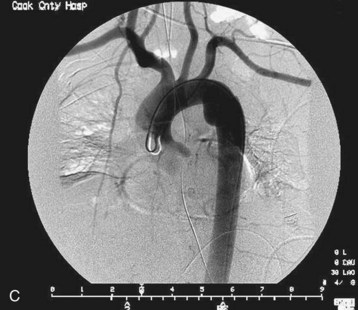

Fig. 78.6 Chest radiographs showing traumatic aortic injury.

C, Traumatic pseudoaneurysm seen on an aortogram.

(B, from Westra SJ, Wallace EC. Imaging of pediatric chest trauma. Radiol Clin North Am 2005;43:267-81; C, image courtesy Scott Sherman, MD.)

With sensitivity near 100%, a normal CT scan rules out traumatic aortic injury.32 If the results are indeterminate, aortography should be performed. Rarely, a positive helical CT angiogram in a stable patient is followed by aortography for further localization of the injury and identification of other injuries, such as a pseudoaneurysm (see Fig. 78.6, B). Advantages of helical CT angiography over aortography are that it is faster, is noninvasive, requires a smaller volume of contrast agent, and provides information about other thoracic injuries. A high index of suspicion and low threshold for performing screening helical CT angiography are required to save patients with traumatic aortic injury who survive to arrive at the ED.

Aortography remains the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of traumatic aortic injury. False-positive and false-negative results are rare but do occur. Better sensitivity with helical CT angiography has been reported. Aortography offers improved localization of injury before surgical repair. Newer techniques such as intravenous digital subtraction angiography have improved the speed while reducing the cost of aortography (see Fig. 78.6, C).

A chest radiograph should be obtained in all patients with suspected penetrating great vessel injury, and all wounds should be noted and marked. The examination should be focused specifically on evidence of mediastinal hematoma, hemothorax, foreign bodies near vessels or in the trajectory of a missile, “fuzzy” missiles created by arterial pulsations, and the absence of a missile in patients with a gunshot wound to the chest, which suggests distal embolization. An angiogram should be obtained to further assess the injuries and plan an operative approach in the rare stable patient. With the added benefit of evaluating nearby structures, helical CT angiography will probably replace aortography in the evaluation of stable patients with transmediastinal penetrating injury.33

Esophageal Injury

Follow-up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Management can be operative or nonoperative. Small, minimally symptomatic or chronic perforations, particularly those involving the cervical esophagus secondary to instrumentation, are most amenable to a nonsurgical approach.34 Consultation with trauma or general surgery specialists for primary surgical repair dramatically improves outcomes.

Diaphragmatic Injuries

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

In the last, or obstructive, phase, incarceration, strangulation, and ischemia develop.35 Additionally, the compressive effects of the intrathoracic bowel on the heart and lung can result in tension enterothorax or viscerothorax.36 In this phase, symptoms of visceral obstruction, ischemia, and ultimately visceral infarction develop. Rarely, tension viscerothorax also develops. Herniation should be considered in any patient with vague complaints of chest or abdominal pain and a history of thoracoabdominal trauma.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The initial chest radiograph should be inspected for the classic diagnostic finding, which is a nasogastric tube or viscera in the left hemithorax. Other important but more subtle signs include an indistinct or elevated left hemidiaphragm and left lower lobe atelectasis. Hemopneumothorax is present in 50% of patients with penetrating injury. Up to 25% of patients with penetrating diaphragmatic injuries have normal chest radiographic findings and no abdominal tenderness. CT scanning is 100% specific but only 66% sensitive for the diagnosis of blunt diaphragmatic injury.37

In the latent phase of injury, the chest radiograph is typically abnormal. Findings can be subtle, such as a unilaterally elevated hemidiaphragm, unilateral pleural thickening, or basilar atelectasis, or can be significant, such as a shift of the mediastinum or viscera evident above the diaphragm. In cases of delayed herniation, upper or lower gastrointestinal contrast-enhanced studies may be needed to demonstrate herniation (Fig. 78.7).

FAST can also be used in the diagnosis of diaphragmatic rupture. The sonographic features of a ruptured diaphragm include nonvisualization of the spleen or heart, poor diaphragmatic movement, elevated diaphragm, liver sliding sign, pleural effusion, subphrenic effusion, or viscera visualized in the thorax.38,39 Traditionally, a diagnostic peritoneal lavage count of less than 10,000 red blood cells/µL is used to rule out a diaphragmatic injury in patients with penetrating thoracoabdominal trauma. Lavage fluid draining from the chest tube is diagnostic. However, diagnostic peritoneal lavage misses up to 25% of diaphragmatic injuries because of bleeding into the chest. Laparoscopy or thoracoscopy is the diagnostic study of choice in patients with high clinical suspicion for diaphragmatic injury not otherwise needing surgery.

Follow-up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Subtle Life-Threatening Emergencies in the Secondary Survey

Traumatic Aortic Injury

Patients may have no external sign of trauma. Never say “she looks too good to have a traumatic aortic injury,” “it was only a lateral impact,” or “he was wearing a belt and the airbag went off.” The patient will look good until the aorta ruptures; with lateral impact in a moving vehicle collision, there may be increased risk for traumatic aortic injury, and restraints alone do not reduce the risk for traumatic aortic injury.

. EAST management of pulmonary contusion and flail chest practice guidelines 2006. Available at http://www.east.org/

Eroglu A, Turkyilmaz A, Aydin Y, et al. Current management of esophageal perforation: 20 years experience. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:374–380.

Holmes JF, Ngyuen H, Jacoby RC, et al. Do all patients with left costal margin injuries require radiographic evaluation for intraabdominal injury? Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:232–236.

2001 Practice management guidelines for emergency department thoracotomy: Working Group, Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Outcomes, American College of Surgeons–Committee on Trauma. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:303–309.

Soreide E, Deakin CD. Pre–hospital fluid therapy in the critically injured patient—a clinical update. Injury. 2005;36:1001–1010.

1 Lee J, Harris JH, Jr., Duke JH, Jr., et al. Noncorrelation between thoracic skeletal injuries and acute traumatic aortic tear. J Trauma. 1997;43:400–404.

2 Gouldman JW, Miller RS. Sternal fracture: a benign entity? Am Surg. 1997;63:17–19.

3 von Garrel T, Ince A, Junge A, et al. The sternal fracture: radiographic analysis of 200 fractures with special reference to concomitant injuries. J Trauma. 2004;57:837–844.

4 Shweiki E, Klena J, Wood GC, et al. Assessing the true risk of abdominal solid organ injury in hospitalized rib fracture patients. J Trauma. 2001;50:684–688.

5 Kemp AM, Dunstan F, Harrison S, et al. Patterns of skeletal fractures in child abuse: systematic review. BMJ. 2008:337. a1518

6 Rainer TH, Griffith JF, Lam E, et al. Comparison of thoracic ultrasound, clinical acumen, and radiography in patients with minor chest injury. J Trauma. 2004;56:1211–1213.

7 Jin W, Yang DM, Kim HC, et al. Diagnostic values of sonography for assessment of sternal fractures compared with conventional radiography and bone scans. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:1263–1268. quiz 1269–70

8 Holmes JF, Ngyuen H, Jacoby RC, et al. Do all patients with left costal margin injuries require radiographic evaluation for intraabdominal injury? Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:232–236.

9 Ullman EA, Donley LP, Brady WJ. Pulmonary trauma emergency department evaluation and management. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:291–313.

10 Gunduz M, Unlugenc H, Ozalevli M, et al. A comparative study of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV) in patients with flail chest. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:325–329.

11 EAST management of pulmonary contusion and flail chest practice guidelines. http://www.east.org/, 2006. Available at

12 Barton ED. Tension pneumothorax. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1999;5:269–274.

13 Bokhari F, Brakenridge S, Nagy K, et al. Prospective evaluation of the sensitivity of physical examination in chest trauma. J Trauma. 2002;53:1135–1138.

14 Kirkpatrick AW, Sirois M, Laupland KB, et al. Hand–held thoracic sonography for detecting post–traumatic pneumothoraces: the extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (EFAST). J Trauma. 2004;57:288–295.

15 Maxwell RA, Campbell DJ, Fabian TC, et al. Use of presumptive antibiotics following tube thoracostomy for traumatic hemopneumothorax in the prevention of empyema and pneumonia—a multi–center trial. J Trauma. 2004;57:742–748.

16 Brasel KJ, Stafford RE, Weigelt JA, et al. Treatment of occult pneumothoraces from blunt trauma. J Trauma. 1999;46:987–990.

17 Seamon MJ, Medina CR, Pieri PG, et al. Follow–up after asymptomatic penetrating thoracic injury: 3 hours is enough. J Trauma. 2008;65:549–553.

18 Wanek S, Mayberry JC. Blunt thoracic trauma: flail chest, pulmonary contusion, and blast injury. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20:71–81.

19 Huh J, Milliken JC, Chen JC. Management of tracheobronchial injuries following blunt and penetrating trauma. Am Surg. 1997;63:896–899.

20 Maron BJ, Estes NAM. Commotio cordis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:917–927.

21 . EAST trauma practice guidelines, EAST blunt cardiac injury guidelines. Available at http://www.east.org/tpg/archive/html/chap2body.html

22 Ismailov RM, Ness RB, Redmond CK, et al. Trauma associated with cardiac dysrhythmias: results from a large matched case–control study. J Trauma. 2007;62:1186–1191.

23 Jackson L, Stewart A. Best evidence topic report. Use of troponin for the diagnosis of myocardial contusion after blunt chest trauma. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:193–195.

24 Ball CG, Williams BH, Wyrzykowski AD, et al. A caveat to the performance of pericardial ultrasound in patients with penetrating cardiac wounds. J Trauma. 2009;67:1123–1124.

25 Rhee PM, Acosta J, Bridgeman A, et al. Survival after emergency department thoracotomy: review of published data from the past 25 years. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:288–298.

26 Branney SW, Moore EE, Feldhaus KM, et al. Critical analysis of two decades of experience with postinjury emergency department thoracotomy in a regional trauma center. J Trauma. 1998;45:87–94.

27 Practice management guidelines for emergency department thoracotomy: Working Group, Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Outcomes, American College of Surgeons–Committee on Trauma. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:303–309.

28 Wise D, Davies G, Coats T, et al. Emergency thoracotomy: “how to do it.”. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:22–24.

29 Cook CC, Gleason TG. Great vessel and cardiac trauma. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89:797–820. viii

30 Horton TG, Cohn SM, Heid MP, et al. Identification of trauma patients at risk of thoracic aortic tear by mechanism of injury. J Trauma. 2000;48:1008–1013.

31 Nagy K, Fabian T, Rodman G, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of blunt aortic injury: an EAST Practice Management Guidelines Work Group. J Trauma. 2000;48:1128–1143.

32 Dyer DS, Moore EE, Ilke DN, et al. Thoracic aortic injury: how predictive is mechanism and is chest computed tomography a reliable screening tool? A prospective study of 1,561 patients. J Trauma. 2000;48:673–682.

33 Stassen NA, Lukan JK, Spain D, et al. Reevaluation of diagnostic procedures for transmediastinal gunshot wounds. J Trauma. 2002;53:635–638.

34 Eroglu A, Turkyilmaz A, Aydin Y, et al. Current management of esophageal perforation: 20 years experience. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:374–380.

35 Reber PU, Schmied B, Seiler CA, et al. Missed diaphragmatic injuries and their long–term sequelae. J Trauma. 1998;44:183–188.

36 Wong P, Vendargon SJ. Tension enterothorax. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2003;11:375.

37 Allen TL, Cummins BF, Bonk RT, et al. Computed tomography without oral contrast solution for blunt diaphragmatic injuries in abdominal trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:253–258.

38 Gangahar R, Doshi D. FAST scan in the diagnosis of acute diaphragmatic rupture. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:387.e1–387.e3.

39 Blaivas M, Brannam L, Hawkins M, et al. Bedside emergency ultrasonographic diagnosis of diaphragmatic rupture in blunt abdominal trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:601–604.