THORACIC SPINE

SPECIAL TEST FOR NEUROLOGICAL DYSFUNCTION

Relevant Special Test

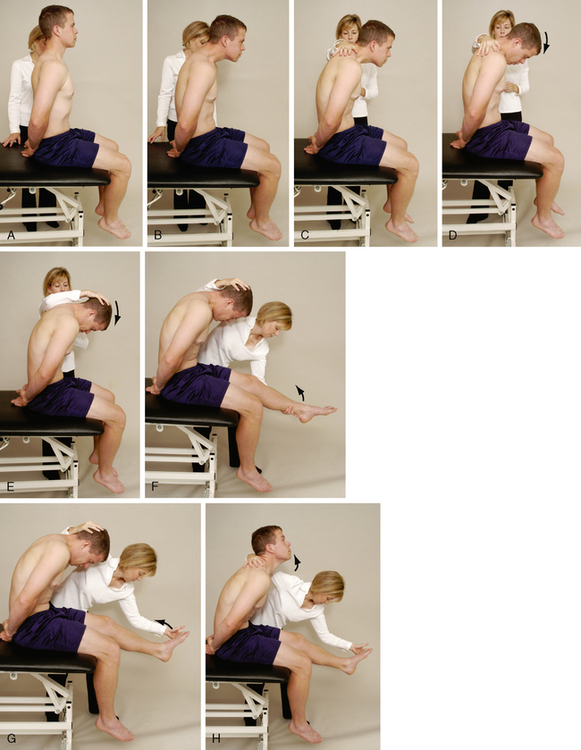

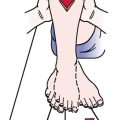

Slump test (sitting dural stretch test)

Epidemiology and Demographics

Thoracic disc herniation. The thoracic spine is reported to be the spinal region least likely to experience a disc herniation. The thoracic spine has been reported to account for 0.25% to 5% of intervertebral disc herniations. One in 1 million patients experiences symptoms of thoracic disc herniation every year. Of these patients, 2% have herniation at the lower thoracic spine (T11-T12), and 70% have herniation in a posterolateral direction. The age range for thoracic disc herniation has been reported to be 11 to 82 years, with a peak age of 40 to 50 years. The condition appears to occur more often in men than in women.6–9

Thoracic compression fracture. Spinal compression fractures occur in more than 750,000 people a year in the United States. About two thirds of spinal compression fractures are never diagnosed, because many patients and families think that back pain is merely a sign of aging and arthritis. Compression fractures are more prevalent in two groups of patients: the elderly, because of osteoporosis and an increased risk of falls; and young adults, as a result of trauma, such as motor vehicle accidents or a fall from a great height.10,11

T4 syndrome. The prevalence of this pathological condition is unknown. Those most prone to development of the syndrome are individuals over 35 years of age. The gender and cultural prevalence also are unknown.12–14

Relevant Signs and Symptoms

Thoracic disc herniation. Disc herniations in the thoracic spine may be asymptomatic. However, patients may complain of intermittent backache, thoracic root pain and paresthesia, and/or spinal cord compression symptoms.

Thoracic compression fracture. A patient with a thoracic compression fracture may complain of pain in the thoracic region over the affected vertebra. The symptoms may be described as severe, sharp, and exacerbated by motion. Pain is noted when the person lifts and carries objects or with breathing. The patient may or may not have signs of cord compression, depending on the magnitude of injury.

T4 syndrome. Patients with T4 syndrome complain of unilateral or bilateral paresthesia in all five hand digits, or in the whole hand, or in the forearm and hand (i.e., glove type [long/short]). The hands may feel hot or cold, swelling may be present, and the patient may complain that the arms feel heavy. Aches and pains may be present in a nondermatomal pattern. The patient may complain that the pain feels like a tight band around the arms. The person also may complain of a combination of neck, upper thoracic, and cranial pain, without abnormal neurological signs.