48 Thoracic Spinal Stenosis

KEY POINTS

Introduction

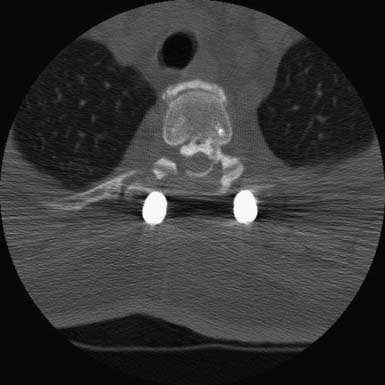

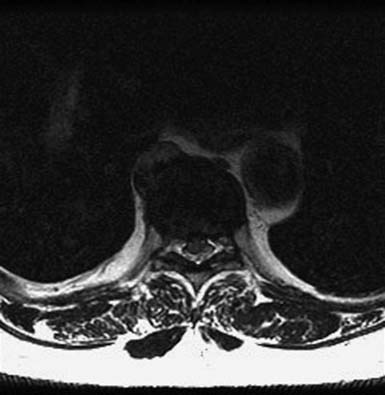

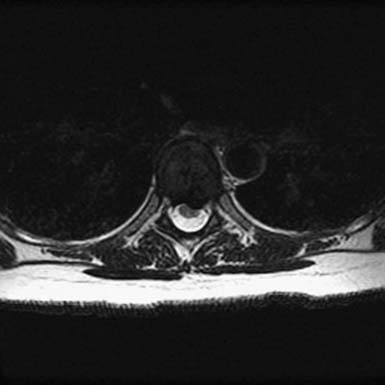

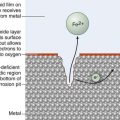

Stenosis of the thoracic spine is a relatively rare condition when compared to stenosis of the cervical or lumbar spine. Because it is unusual, a full understanding of the condition’s epidemiology and clinical presentation is limited, yet like stenosis in other spinal regions, its causes are numerous. These include ossification of the ligamentum flavum (OLF) (Figure 48-1) or posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) (Figures 48-2 and 48-3), herniation of intervertebral discs (Figures 48-4 and 48-5), and spondylosis. Other causes include neoplastic lesions, facet cysts, vascular malformations, and fracture. Stenosis of the thoracic spine typically presents with a variable combination of three main symptoms: back pain, radiculopathy, and myelopathy.

FIGURE 48-4 Thoracic disc herniation, T8-9, with symptomatic cord compression and T2 signal change of the cord.

Much of what is known about thoracic stenosis has been derived from the experience of Japanese practitioners. OLF is cited as the most common cause of thoracic spinal stenosis. Although case reports of OLF with thoracic myelopathy in whites and North Americans have been published,12 patients of Asian descent are most frequently affected. Up to 20% of Asians older than 65 years of age have some degree of thoracic stenosis due to OLF.3 Aizawa et al, in a retrospective study of 265 Japanese patients, found OLF to account for more than half of all cases of thoracic myelopathy.4 Middle-aged men had the condition more frequently than women. It is not yet clear why this condition has a gender discrepancy and why it tends to occur in younger patients than those with cervical or lumbar stenosis.

Because OLF and OPLL are unusual among Westerners, much of the European and North American literature focuses on thoracic intervertebral disc disease as the primary etiology of thoracic spinal stenosis. As with OLF and OPLL, thoracic disc herniation is overall an unusual cause of thoracic back pain, radiculopathy, and myelopathy. Studies suggest than it affects males most frequently and tends to occur between the fourth and sixth decades.4

Pathology

OLF occurs as a normal part of the aging process and rarely leads to stenosis. Histologically, the normal ligamentum flavum is composed of significant amounts of elastin that, with aging and degeneration, is progressively replaced by collagen, fragments of bone, cartilage, and fibrous tissue.5 Pathologic ossification is characterized by extreme progression of these processes leading to overgrowth and, ultimately, canal and foraminal stenosis. The precise mechanisms of pathologic OLF have not yet been clearly determined. It has been suggested that high mechanical stress of the thoracolumbar junction leads to degeneration of the facets and intervertebral discs, initiating progressive injury of the ligamentum flavum in this region.6 Ossification then proceeds in response to repetitive injury. This may explain why OLF occurs more frequently in the lower thoracic spine. Although plausible, this theory has been questioned because the cervical and lumbar spinal regions are more mobile than the thoracic spine, yet ossification in these locations is less common.7 It is also rare for OLF lesions to extend across multiple levels. Medical comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, abnormalities in calcium metabolism, hypoparathyroidism, and Paget disease may play a significant role and have been associated with pathologic OLF.8,9 The higher incidence of OLF in the Japanese population clearly suggests a genetic etiology.

OLF associated with thoracic myelopathy most typically occurs in the lower thoracic spine.10 In their epidemiologic study, Aizawa et al found that T11-12 was the most common site of compression, followed by T10-11 and T9-10. When OPLL was the cause, T1-2 was affected most commonly, followed by T2-3 and T3-4.11

As with OLF and OPLL, isolated traumatic injury to thoracic intervertebral discs is rare. The splinting effect of the rib cage as well as the vertical orientation of the thoracic facets serves to reduce the forces on thoracic discs compared to those in the lumbar spine. This is thought to decrease the incidence of discal injury in the thoracic area. Degeneration of thoracic discs due to aging can occur as well, being most common in the fourth through the sixth decades of life, with males affected more frequently than females. Thoracic disc herniation tends to occur in the midline or just lateral to the midline, and predominates in the lower thoracic levels (Figures 48-6 and 48-7).12 Wood et al reviewed 90 MRI scans of asymptomatic patients and demonstrated that, often, thoracic disc herniations exist without symptoms.13 An additional study by Wood et al showed that these herniations do not frequently progress.14

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of thoracic stenosis ranges from simple back pain to frank myelopathy. Thoracic back pain is the most common presentation of a disc herniation, with patients describing the pain as “passing through their chest.” When lower thoracic discs are affected, the pain may radiate to the abdomen, flank, or groin. Paresthesias, numbness, intercostal neuralgias, unsteady gait, and fatigue while walking may also be present. When myelopathy occurs, it often presents itself as trunk and lower extremity weakness (especially of proximal musculature), spasticity, and sensory loss. The upper extremities should be spared. Alterations in bladder control can occur. Because of the similarities in presentation, and the infrequency of thoracic spinal stenosis, thoracic myelopathy can often be confused with lumbar and/or cervical stenosis, leading to delays in diagnosis.

Diagnosis

Physical findings of patients with thoracic myelopathy are similar to those seen in lumbar and cervical stenosis. Lower extremity weakness, hyperreflexia, decreased sensation, sphincter malfunction, loss of abdominal reflexes, and gait instability can be present. In addition, patients may localize their pain and hypesthesia in a thoracic distribution. Complete paraplegia due to thoracic spinal cord compression has also been documented.15

Patients with symptoms of thoracic spinal stenosis often may have findings on plain x-rays that suggest the etiology of the condition. Destructive lesions such as tumors and vascular malformations may be directly visualized, as can some fractures. When there is OLF, beak-like bony densities are characteristically seen projecting into the posterior aspect of the spinal canal on the lateral x-ray.16 Asymptomatic disc herniations are poorly visualized with plain x-ray, unless there is a significant amount of ossification.17 Unless there is an underlying metabolic abnormality, laboratory studies are typically normal.

Studies have compared the utility of CT and MRI in the diagnosis of thoracic spinal cord compression due to ossification of spinal ligaments.18 Both CT and MRI scanning may play a role in the diagnosis of thoracic spinal cord compression. Plain CT provides detailed information regarding the bony anatomy and degree of ossification of the spinal ligaments, as well as ossification of intervertebral discs and facet hypertrophy. MRI, on the other hand, helps to define the extent of spinal cord injury and identify facet cysts. In the setting of OLF, CT myelography is unnecessary, as it adds little to the data collected by MRI, and the contrast injection occasionally exacerbates symptoms of stenosis. If MRI is contraindicated in a patient, such as with a pacemaker, CT myelography is the study of choice.

Treatment

Thoracic myelopathy due to OLF or OPLL is not well treated by conservative methods such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications and physical therapy. Surgical decompression is often required when stenosis results in myelopathy or debilitating radiculopathy. The best mode of surgical treatment for stenosing OLF is not well defined in the literature. Depending on the extent of compression, laminoplasty, partial or total laminectomy, circumferential decompression, and decompression with fusion have been proposed. The proponents of laminoplasty suggest that this procedure may produce less instability than other modes of decompression.19 Prognosis after surgery depends on the extent of compression and neurological deficit. Recurrent stenosis has been documented, making routine follow-up necessary.20

For thoracic stenosis due to OPLL, multiple treatment options have been described, including laminectomy, laminoplasty, resection of the PLL, anterior decompression and fusion via thoracotomy, and posterior decompression and fusion.21,22 Anterior decompression with fusion has been supported by a recent long-term study.23Fujimura et al reviewed the data of 33 patients followed for more than 5 years after anterior decompression and fusion was performed for myelopathy in the thoracic spine due to ossification of the PLL. Their results suggested that anterior decompression with fusion can lead to favorable long-term results. They indicated, however, that patients with OPLL that affects multiple levels and those with concurrent OLF may not do as well in long-term follow-up.

Posterior surgical approaches provide an alternative treatment option for myelopathy due to OPLL, particularly when there is also OLF. It is suggested that, for OPLL, posterior decompression alone may not be sufficient due to draping of the spinal cord over the kyphotic thoracic spine. Some advocate a circumferential decompression through an isolated posterior approach.24 High complication rates have been documented with this treatment, however, particularly when more than five levels are decompressed. In a study by Masahiko et al, as many as 33% of patients had deterioration in their neurological status following surgery. Both the relatively avascular nature of the thoracic spinal cord and adhesion of dural sac to the PLL are thought to contribute to these complications. Even higher rates of neurological deterioration have been seen with laminectomy alone, while lower rates have been reported with posterior decompression and fusion.25 In theory, performing a laminectomy without fusion further destabilizes the spine and subjects the injured spinal cord to additional stresses that lead to a further decline in neurological function. Masashi et al suggested that in the neurologically intact patient, resection of the PLL is an acceptable treatment, but for patients with preoperative spinal cord injury, removal of the PLL increases the risk of paralysis.26

Many patients with thoracic disc herniations are asymptomatic. When symptoms do exist, unlike patients with OPLL and OLF, conservative treatment and time can be sufficient to treat the majority of herniations. Modification of activities, physical therapy, and the careful use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs are the mainstays of conservative care. The literature suggests that less than 2% of thoracic discs require surgical treatment.27 When conservative care fails to alleviate symptoms after 4 to 6 weeks, a neurological deficit progresses, or there is evidence of worsening myelopathy, surgical treatment is warranted.

Operative care of patients with thoracic disc herniations requires assessing several factors to determine operative risk and approach. Depending on the location and nature of the disc herniation, anterior, thoracoscopic, lateral, or posterior approaches may be used, the details of which are largely beyond the scope of this chapter. In general, anteriorlyoriented lesions require a direct ventral approach such as a transthoracic, thoracoscopic, or posterolateral (e.g., costotransversectomy, extracavitary) technique for safe resection that avoids cord manipulation, with bony reconstruction as necessary. Pulmonary function tests should be performed on patients with questionable pulmonary reserve if thoracotomy is considered. Discal calcifications, which are more common in the thoracic spine,28 are associated with a greater degree of dural adhesion or associated dural calcification. Such information is important for the treating surgeon in deciding how much disc to remove from the dura, and whether concomitant dural resection needs to be considered. Once in the operating room, it is essential to identify the correct disc for resection. Sagittal CT reconstructions or MR images are essential to determine the appropriate level, and plain radiography or fluoroscopy in the operating room is standard practice for localization.

For most lateral soft disc herniations, the preferred approach is posterior and usually involves a pediculofacetectomy, typically perfomed by transpedicular or transfacet technique rather than laminectomy. Significant complications have been reported with posterior laminectomy alone,29 including cord contusion and lack of improvement of symptoms. The need for fusion following thoracic disc removal remains controversial but generally depends on the assessed degree of stability of the region following decompression. It may be beneficial to resect a significant amount of vertebral body in cases of multilevel disc disease, or when the disc is in the lower thoracic spine, which may render the spine unstable and require secondary fusion.

Other Causes For Thoracic Spinal Stenosis

Neoplasms

Both intramedullary and extramedullary spinal cord tumors can lead to thoracic myelopathy and must be considered as a possible etiology in every older patient with thoracic spinal stenosis. In their experience treating 78 patients with intramedullary spinal cord tumors, Sandalcioglu et al found that 32% of the tumors were located in the thoracic spine. Low-grade neuroepithelial tumors, ependymomas, astrocytomas, vascular tumors, and metastatic lesions were identified. The most important predictor of postoperative neurological status was a patient’s preoperative neurological function.30 Compared to patients with intramedullary tumors in the cervical or lumbar spine, these authors found that those with thoracic lesions had a higher surgical morbidity. This most likely reflects the regional vulnerability of the thoracic cord due to tenuous blood supply, constricted canal anatomy, and kyphosis. When intramedullary spinal cord tumors are identified, decompression and tumor removal can be performed by laminectomy or laminoplasty.

Metastatic disease to the thoracic spine is more common than metastasis to the cervical or lumbar spine, due to the greater relative size and bony blood supply of the thoracic region. Lesions from lung, breast, prostate, and gastrointestinal carcinomas, as well as other tumor types, are known to metastasize to the thoracic spine. Until recently, many authors could not define the best mode of treatment for extramedullary spinal cord tumors with cord compression causing neurological symptoms. Earlier studies looking at laminectomy alone or laminectomy in combination with radiotherapy did not show surgery to be beneficial.31–33 The importance of surgical decompression, however, was shown in a randomized multicenter trial by Patchell et al, who compared the outcomes of 101 patients treated with either radiotherapy alone or a combination of radiotherapy and decompressive surgery.34 All but 13 of the patients had tumors in the thoracic spine. The median age of their study group was 60. The authors found that patients treated with a combination of postoperative radiotherapy and decompressive surgery were significantly better in terms of ambulatory status, functionality, maintenance of urinary continence, strength, and overall survival than those treated with radiation alone. Their data also suggested that laminectomy may not always be the best mode of treatment. Rather, approaching the lesion directly: anterior tumors anteriorly, posterior tumors posteriorly, and lateral tumors laterally may offer the best results for decompression (see Figure 48-6).

Synovial Cysts

Rare cases of synovial cysts leading to thoracic myelopathy have been reported. Graham et al outlined a case in which a 54-year-old woman developed right lower extremity weakness secondary to a cyst at T11-12.35 The cyst was successfully excised via a laminectomy and the patient had a full recovery. Aspiration has been used as a treatment for synovial cysts in the lumbar spine and might prove to be a useful treatment option in the thoracic spine.

PROGNOSIS

An understanding of the long-term results of surgical treatment of thoracic spinal stenosis due to OLF is limited due to the lack of sufficient study. The literature suggests that a number of factors may make surgical outcomes less favorable. These include a longer duration of symptoms prior to decompression,36 the presence of a proximal stenotic lesion,37 and a greater degree of stenosis.38 Another study looking at OLF did not show an association between preoperative symptom duration and results of surgery, although only 24 patients were evaluated.39 As with the importance of the duration of symptoms, the data are also not clear on how preoperative neurological status affects surgical outcome. A meta-analysis by J. Anamasu et al suggests that the larger, more recent studies indicate a positive association between preoperative neurological function and surgical outcomes.40 Other studies have highlighted some of the long-term complications of thoracic decompressive surgery, including the development of late kyphotic deformities and spondylosis.41,42

1. Van Oostenbrugge R. Spinal cord compression caused by unusual location and extension of ossified ligamenta flava in a Caucasian male: a case report and literature review. Spine. 1999;24:486-488.

2. Kruse J. Ossification of the ligamentum flavum as a cause of myelopathy in North America: report of three cases. J. Spinal Disord. 2009;13(1):22-25.

3. T. Shiraishi. Thoracic myelopathy due to isolated ossification of the ligamentum flavum. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br.. 1995;77:131-133.

4. Aizawa T. Thoracic myelopathy in Japan: epidemiological retrospective study in Miyagi prefecture during 15 years. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2006;210(3):199-208.

5. Ho P.S.P. Ligamentum flavum: appearance on sagittal and coronal MR images. Radiology. 1988;168:469-472.

6. Payer M. Thoracic myelopathy due to enlarged ossified yellow ligaments. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2000;92(1):105-108.

7. Epstein N.E. Ossification of the yellow ligament and spondylosis and/or ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the thoracic and lumbar spine. J. Spinal Disord.. 1999;12:250-256.

8. Vera C.L. Paraplegia due to ossification of the ligamenta flava in x-linked hypophosphatemia: a case report. Spine. 1997;22:710-715.

9. Resnick D. Calcification and ossification of the posterior spinal ligaments and tissues. In Resnick D., Niwayama D., editors: Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders, ed 2, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1988.

10. Yonenobu K., et al. Thoracic myelopathy secondary to ossification of the spinal ligament. J. Neurosurg. 1987;66:511-518.

11. T. Aizawa, Thoracic myelopathy in Japan: epidemiological retrospective study in Miyagi prefecture during 15 years.

12. Rogers M.A. Surgical treatment of the symptomatic herniated thoracic disc. Clin. Orthop.. 1994;300:70-78.

13. Wood K.B. Magnetic resonance imaging of the thoracic spine: evaluation of asymptomatic individuals. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am.. 1995;77:1631-1638.

14. Wood K.B. The natural history of asymptomatic thoracic disc herniations. Spine. 1997;22:525-530.

15. Takahata M. Clinical results and complications of circumferential spinal cord decompression through a single posterior approach for thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine. 2008;33(11):1199-1208.

16. Xiong, et al. CT and MRI characteristics of ossification of the ligamenta flava in the thoracic spine. Eur. Radiol.. 2001;11:1798-1802.

17. Rogers M.A. Surgical treatment of the symptomatic herniated thoracic disc. Clin. Orthop.. 1994;300:70-78.

18. Xiong, et al. CT and MRI characteristics of ossification of the ligamenta flava in the thoracic spine. Eur. Radiol.. 2001;11:1798-1802.

19. Okadak O.S. Thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the ligamentum flavum: clinicopathologic study and surgical treatment. Spine. 1991;16:280-287.

20. K. Yonenobu. Thoracic myelopathy secondary to ossification of the spinal ligament. J. Neurosurg.. 1987;66:511-518.

21. Y. Fujimura. Long-term follow-up study of anterior decompression and fusion for thoracic myelopathy resulting from ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine. 1997;22(3):305-311.

22. Yamazaki M. Clinical results of surgery for thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: operative indication of posterior decompression with instrumented fusion. Spine. 2006;31(13):1452-1460.

23. M. Takahata, Clinical results and complications of circumfrential spinal cord decompression through a single posterior approach for thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament, Spine 33 (11): 1199–1208

24. Yamazaki M. Clinical results of surgery for thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: operative indication of posterior decompression with instrumented fusion. Spine. 2006;31(13):1452-1460.

25. Masashi. Clinical results of surgery for thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, operative indication of posterior decompression with instrumented fusion. Spine. 2006;31(13):1452-1460.

26. Stillman C.B. Management of thoracic disc disease. Clin. Neurosurg.. 1992;38:325-352.

27. Severi P. Multiple calcified thoracic disc herniations: a case report. Spine. 1992;17(4):449-451.

28. C.A. Arce. Thoracic disc herniation: improved diagnosis with computed tomographic scanning and a review of the literature. Surg. Neurol.. 1985;23:356-361.

29. Sandalcioglu I.E., Gasser T., Asgari S. Functional outcome after surgical treatment of intramedullary spinal cord tumors: Experience with 78 patients. Spinal Cord. 2005;43:34-41.

30. Sorensen P.S. Metastatic epidural spinal cord compression: results of treatment and survival. Cancer. 1990;65:1502-1508.

31. Young R.F. Treatment of spinal epidural metastases: randomized prospective comparison of laminectomy and radiotherapy. J. Neurosurg.. 1980;53:741-748.

32. Findley G.F.G. Adverse effects of the management of malignant spinal cord compression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psych.. 1984;47:761-768.

33. Patchell R.A. Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2005;366:643-648.

34. E. Graham, Myelopathy induced by a thoracic intraspinal synovial cyst: case report and review of the literature, Spine 26(17): E392–394.

35. Miyakoshi N. Factors related to long-term outcome after decompressive surgery for ossification of the ligamentum flavum of the thoracic spine. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2003;99:251-256.

36. Chen C.J. Intramedullary high signal intensity on T2-weighted MR images in cervical spondylitic myelopathy: prediction of prognosis with type of intensity. Radiology. 2001;221:789-794.

37. K. Shiokawa. Clinical analysis and prognostic study of ossified ligamentum flavum of the thoracic spine. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2001;94:221-226.

38. Cheng-Chin L. Surgical experience with symptomatic thoracic ossification of the ligamentum flavum. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2005;2:34-39.

39. J. Inamasu. A review of factors predictive of surgical outcome for ossification of the ligamentum flavum of the thoracic spine. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2006;5:133-139.

40. Cheng-Chin L. Surgical experience with symptomatic thoracic ossification of the ligamentum flavum. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2005;2:34-39.

41. Palumbo M.A. Surgical treatment of thoracic spinal stenosis: a 2- to 9- year follow-up. Spine. 2001;26(5):558-566.

42. Palumbo M.A. Surgical treatment of thoracic spinal stenosis: a 2- to 9- year follow-up. Spine 5. 2001;26:558-566.