Chapter 113 Thoracic and Thoracolumbar Spinal Tumors

Regional Challenges

Primary Spinal Tumors

Primary spinal tumors are an uncommon subset of the tumors affecting the thoracic and lumbar spine. A review of data from the Leeds Tumor Registry shows that 2.8% of patients had tumors of the spine.1 In the United States, the incidence of primary tumors of the spine per 100,000 person years is estimated at 2.5 to 8.5.2 According to the series published by Weinstein and McLain, which reviewed 82 primary neoplasms of the spine over a 50-year period, nearly two thirds of all thoracic, lumbar, and sacral tumors were malignant.3 Rarely, these tumors present the possibility of a cure via surgical resection. A full description of primary spinal tumors is presented in Chapter 106.

Metastatic Spinal Tumors

Metastatic spinal tumors are the most common spinal tumors treated by the spine surgeon. At autopsy, 70% of patients who died of cancer have some form of vertebral metastasis.4 Spine surgeons, therefore, must have a clear understanding of the behavior of the primary tumor. Close consultation with medical oncologists and other specialists, however, is critical. Medical and adjunctive treatments have improved the quality of life and lengthened the survival of cancer patients.

Tumor type has been found to correlate with outcome. More aggressive primary tumors portend a worse long-term prognosis. Wise et al. reported that the longest mean survival times after the diagnosis of spinal metastasis were for myeloma (40.3 months), breast cancer (32.3 months), and prostate cancer (26.9 months), and shortest for lung cancer (12.3 months) and adenocarcinoma.5 The patient’s neurologic status, extent of disease, nutrition, overall health, and expected length of survival are other important considerations when deciding whether the patient is a candidate for extensive spine surgery. Most surgeons agree that metastatic spinal tumor surgery should be limited to patients who have an estimated life expectancy greater than 3 months. In an effort to better determine a patent’s life expectancy, Tokuhashi et al. presented a scoring system to be used in the preoperative evaluation of patients with metastatic spinal tumors.6 Scores of 0 to 2 points are assigned for each of six parameters (Table 113-1). The patient’s general health, the number of extraspinal skeletal metastases, the number of metastases to the spine, the status of metastases to internal organs, the site of the primary tumor, and the patient’s neurologic status are all weighted parameters in this scoring system. In addition to using this scoring system, spine surgeons are encouraged to consult with the patient’s medical and radiation oncologists, because multimodal treatment may offer the patient an even longer survival than otherwise predicted.

Table 113-1 Tokuhashi Scoring System for Preoperative Evaluation of Patients with Metastatic Spinal Tumors

| Parameter | Score |

|---|---|

| General Condition | |

| Poor | 0 |

| Moderate | 1 |

| Good | 2 |

| No. of Extraspinal Bone Metastases | |

| >3 | 0 |

| 1 or 2 | 1 |

| 0 | 2 |

| No. of Metastases in the Spine | |

| >3 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 |

| Metastases to Major Internal Organs | |

| Irremovable | 0 |

| Removable | 1 |

| None | 2 |

| Primary Site of Cancer | |

| Lung, stomach | 0 |

| Kidney, liver, uterus, other | 1 |

| Thyroid, prostate, breast, rectum | 2 |

| Myelopathy | |

| Complete | 0 |

| Incomplete | 1 |

| None | 2 |

Data from Tokuhashi Y, Matsuzaki H, Toriyama S, et al: Scoring system for the preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 15:1110-1113, 1990.

Surgical Margins

All discussions regarding the surgical resection of tumors, regardless of the surgical discipline, reference the type of margin that is achieved when the tumor is removed. Surgical resections may be defined as either intralesional or en bloc. An intralesional resection is, by definition, a surgical resection in which the tumor is removed in a piecemeal fashion. An en bloc resection is a tumor resection in which the capsule of the tumor itself is not violated. Intralesional resections rarely offer the possibility of complete eradication of the tumor. The reliability of an en bloc resection to relieve the patient of tumor burden depends on the margins that are obtained during the surgical resection. These margins may be described as intralesional (if the tumor capsule is violated), marginal, wide, and radical. Intralesional resections are self-explanatory. Marginal resections imply that the entirety of the tumor burden is removed, but little or no normal tissue is resected along with the tumor. Wide resection, by definition, includes a component of normal tissue that is removed along with the tumor. By taking a wide en bloc resection, the tumor tissue is not visualized at the time of the resection, as it is completely encapsulated by a margin of normal tissue. A radical resection, by definition, removes the entire organ along with the blood and lymph supply to the organ. In spine surgery, a true radical resection is rarely, if ever, possible. In the event that an en bloc resection can even be performed, a wide resection often is the only possibility.

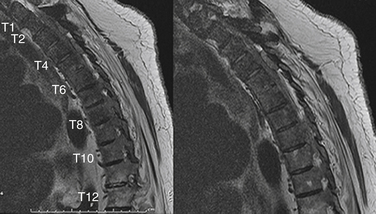

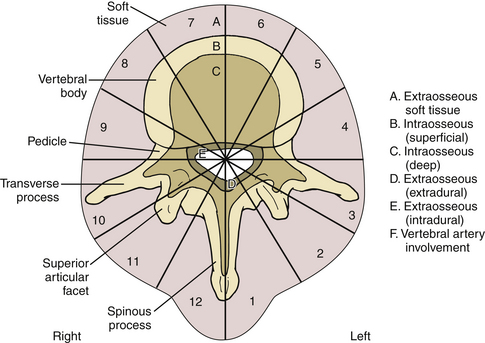

With respect to spinal tumor surgery, regional classification systems have been developed. Weinstein first popularized this type of classification system. In Weinstein’s classification system, tumors were defined as intraosseous (A), extraosseous (B), and distant spread (C).7 The zones were further subdivided with respect to the tumor’s location on the vertebrae. Other groups have attempted to define spinal tumor location in a similar manner. Most recently, the Spine Oncology Study Group examined observer reliability for two of these classification systems. They found that there was moderate interobserver reliability and substantial intraobserver reliability. The Spinal Oncology Study Group thought that changing the orientation of the diagram of the zones to fit the convention of MRI and CT axial cuts made the system more user friendly (Fig. 113-1). With respect to the classification system described by Weinstein, tumors that have extraosseous extension rarely are resectable in an en bloc manner due to the risks posed to the vascular and visceral structures present in the thoracic and thoracolumbar regions.8

FIGURE 113-1 This classification system divides tumors by vertebral location.

(From Chan P, Boriani S, Fourney DR, et al: An assessment of the reliability of the Enneking and Weinstein-Boriani-Biagini classifications for staging of primary spinal tumors by the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine [Phila Pa 1976] 34:384–391, 2009.)

For an isolated metastatic tumor, the extent of resection has been related to patient survival. Sundaresan et al. reported that gross total resection of spinal tumors leads to a median survival of more than 2 years, compared with a historic median survival of 6 months for less aggressive resections.9 Tomita et al. reported on 28 patients who had undergone en bloc vertebrectomy with a mean survival of 38.2 months.10 Babat and McLain recommend that isolated metastases from less eminently lethal tumors such as breast, prostate, and kidney tumors should be managed similarly to primary tumors of the spine.11

Spinal Stability

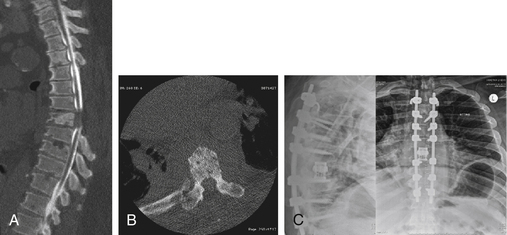

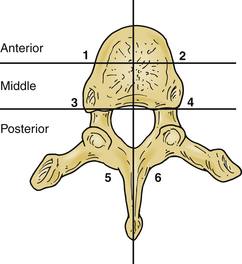

One of the primary indications for surgery for tumors in the thoracic or thoracolumbar spine is the preservation of spinal stability. Kostuik et al. developed a system to evaluate the stability of spinal tumors based on the three-column classification of Denis.12 Most spine surgeons are familiar with this model, which divides each vertebral segment into an anterior column, a middle column, and a posterior column. Unlike the Dennis classification system, these columns are further divided in half in the sagittal plane to create six zones (Fig. 113-2). Destruction of fewer than three of the six zones is considered to be stable. Further bony involvement, specifically three- and four-zone bone involvement, is considered relatively unstable. Five- to six-zone destruction is considered markedly unstable, potentially benefiting from surgical intervention (see Fig. 113-2). Other researchers have recommended that the destruction of more than 50% of the vertebral body warrants either prophylactic treatment or surgical stabilization.13 Other modalities have been reported in the literature to be potentially helpful in this region of the spine. Specifically, minimally invasive techniques such as kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty have been found to aid both pain relief and spinal stability in this region.14

FIGURE 113-2 Regions of bony destruction described by Kostuik and Errico.12 This classification system divides tumors by the extent of vertebral involvement. The more zones occupied by tumor, the less stable the vertebral segment.

Dimar et al.15 used a cadaveric model of bone destruction to examine pathologic thoracic vertebral fracture risk. This group found that the force required to cause a vertebral fracture correlated with a value they called the vertebral strength index, which is equivalent to the product of the remaining intact vertebral body and the bone mineral density. Despite these guidelines, there is no consensus with respect to the absolute amount of bony destruction that would compel a spine surgeon to stabilize a threatened thoracic or thoracolumbar spine. Surgeons are again reminded to consider the patient and his or her disease state as a whole.

Neurologic Stability

Few would argue that in the face of a progressive neurologic deficit, decompression surgery is necessary. Historically, surgery has involved a laminectomy despite the predominance of compressive tumors found anteriorly in the vertebral body. The results of these procedures were disappointing: only 35% of patients with an incomplete neurologic deficit experienced any appreciable improvement, and no patients with a complete neurologic deficit improved.16

The development of ventral surgical approaches to the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine has markedly improved patient outcomes for the surgical decompression of spinal tumors. Siegal et al. reported on 47 operative procedures performed in 40 patients with malignant epidural tumors. The indications for surgery in this group were a worsening neurologic status after previous radiation therapy in 18 procedures, the need for a tissue diagnosis in 16, a radioresistant tumor in 7, neurologic deterioration while receiving radiation therapy in 5, and a pathologic fracture-dislocation in 1 patient. Seventy percent of the procedures from this study were performed in the thoracic spine. Before surgery, all of the patients had some form of neurologic deficit. Patients were still able to walk before 12 (26%) of the procedures, were paraparetic prior to 23 procedures (49%), and were paraplegic prior to 12 procedures (26%). Bowel and bladder dysfunction was present before 25 procedures (53%). The outcome of only 44 procedures could be evaluated, because 3 patients died postoperatively. The patients were able to walk following 35 (80%) of the procedures, and were paraparetic after 8 (18%) of the procedures, and 1 patient was still paraplegic after the procedure. The patients regained normal sphincter control after 41 (93%) of the procedures. Three (6%) of the procedures were followed by the death of the patient, and complications occurred after 5 (11%) of the procedures. The authors felt that in view of the large number of patients who regained the ability to walk after ventral decompression, the role of surgical intervention as a primary treatment for epidural compression by a malignant tumor should be reconsidered.17 Before this study, oncologists had favored the use of radiation therapy and chemotherapy alone due to the high complication rate and poor outcomes for surgical patients.18

Kostuik et al.12 later compared the results of ventral and dorsal surgery for spinal tumors. They reported neurologic return in 40% of patients who underwent dorsal decompression and 71% in those with ventral decompression. Patients with ventral metastases isolated to one or two continuous segments were found to have substantially better outcomes when ventral reconstruction was performed. Weinstein and Kostuik19 later reviewed the literature and found far better outcomes for patients undergoing ventral decompression. A satisfactory outcome was achieved in 37% of patients after a dorsal decompression and 80% of patients after a ventral decompression. As a result, interest in surgical decompressions of spinal tumors was renewed.20

Onimus et al.21 reported on their series of 100 surgical decompressions of metastatic spinal tumors. Fifty-eight patients underwent a ventral approach, 33 patients underwent a dorsal decompression, and 9 patients underwent a combined approach. Mean follow-up was 13.5 months. By then, 89 patients had died in follow-up. The average survival was 10 months. The mean survival was 7 months for patients with lung metastasis, 12 months for those with breast metastasis, and 24 months for patients with prostate metastasis. Intractable pain was observed in all patients with lung cancer. All patients had been optimized on analgesic medication, with 57 patients receiving opioid-derived medications. Walking was not possible for 50 patients. Thirty-eight patients presented with at least some form of neurologic deficit. Surgical treatments included anterior surgery (58 patients), posterior surgery (33 patients), and a combined surgical approach (9 patients). The mean follow-up for this study was 13.5 months. Neurologic status was improved in 30 of 38 patients, and pain was improved in 62 patients. The authors concluded that pain depended on both the character of the bony lesion and the type of primary tumor. They also emphasized that the surgical approach should be dictated entirely by the tumor’s location. Although not critically analyzed in this paper, the authors believed that even though patient survival may be limited, the surgical treatment of vertebral metastasis was beneficial in terms of functional status, such as retained ambulatory ability and retained bladder and bowel function, which were found in more than 80% of their patients.

Surgical Considerations for Patients Undergoing Radiation Therapy

The role of radiation versus surgical decompression has been well debated in the literature.22,23 Early reports had touted the relative effectiveness of radiation in patients with spinal cancer. It is well known that radiation can interfere with wound healing, however, which is potentially disastrous in this patient population. Gilbert et al.18 reported no significant difference in the outcome of patients who underwent laminectomy and radiation compared with patients who received radiation alone. A large number of complications were noted in the laminectomy population, including an increased incidence of spinal instability and wound complications. This study did not examine patients who had undergone ventral decompression and fusion.

In 2002, Sundaresan et al.23 reported on the outcomes of 80 patients with solitary metastatic spinal lesions treated with a variety of surgical, medical, and radiation therapy approaches. Complete follow-up information was available on all patients. Clinical parameters, such as the neurologic grade, preoperative pain, and outcome measures, were available for analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed on all patients. Survival varied by tumor type, with the best prognosis noted in patients with either kidney or breast cancer. Although 48 patients (60%) had been ambulatory preoperatively, 78 (98%) were ambulatory after surgery, including 94% of those who initially had been nonambulatory. Although the patient population is heterogeneous, it was thought that a combined approach using radiation and surgery was beneficial for patients.

In 2005, a landmark article by Patchell et al. reported on the results of a randomized, multi-institutional, non-blinded trial that randomly assigned patients with spinal cord compression to either surgery followed by radiation therapy (n = 50) or to radiation therapy alone (n = 51).24 The primary end point of the study was the ability to walk, with secondary outcomes of urinary continence, muscle strength and functional status, the need for analgesic medication, the need for corticosteroids, and, finally, survival rates examined. After an interim analysis, the study was terminated early, because significantly more patients who underwent a surgical decompression—42 of 50 patients (84%)—were able to walk, compared with the 29 of 51 patients (57%) who were able to walk after radiation alone. Surgically treated patients also were able to walk significantly longer than those who underwent radiation alone (median, 122 days vs. 13 days, P = .003). The need for corticosteroids, as well as analgesics, also was significantly reduced for the surgical group. Since the publication of this landmark article, most spinal oncologists believe that surgical decompression for epidural disease is the most effective means of preserving neurologic function and retaining ambulatory status.

Technical Aspects of the Surgical Approach

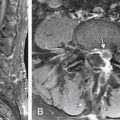

Dorsal Approach

As described earlier, dorsal approaches are indicated for patients who have spinal cord compression due to tumor in the dorsal elements. As also discussed earlier, one retrospective review demonstrated neurologic improvement in as few as 24% of patients undergoing a posterior decompression for a spinal tumor.25 This study specifically examined patients who underwent a simple laminectomy (Fig. 113-3). More recently, Bauer26 demonstrated significant neurologic improvement in patients undergoing a more aggressive dorsal approach that included pedicle resection and the removal of ventral compressive lesions, along with segmental stabilization. Seventy-six percent of patients had substantial improvement in their neurologic status, with most retaining this improvement until their deaths. Rigid segmental stabilization is thought to offer the best chance of a satisfactory outcome after an isolated dorsal decompression, because it prevents kyphosis. Familiarity with this approach is nearly universal. A midline incision is made, and the paraspinal muscles are elevated from the involved segments. A careful dorsal decompression may be completed as described in Chapter 53. In most cases, the only possible resection is an intralesional resection. However, there are occasions when a marginal resection is possible, depending on the location of the tumor in the vertebra.

Ventral Approach

In the 1980s, ventral approaches for the treatment of spinal metastasis gained popularity. Harrington believed that if the dorsal elements had minimal or no tumor involvement, their inherent tensile stability would remain intact, and a spine decompression could be accomplished entirely through the ventral approach.27 Patients are positioned in a full lateral decubitus position with an ancillary roll placed under the dependent arm. The side (right or left) of the approach usually is dictated by the area of tumor compression. If neither side is more involved, the spine often is approached from the right side at or above T5 to avoid the arch of the aorta. Below T5, the spine is approached from the left to minimize retraction on the liver. Surgeons typically select the intercostal space one or two segments above the vertebral body for their approach. After skin incision, a rib typically is dissected in a subperiosteal fashion and resected as far dorsal as possible. The pleura usually is entered at the level of the rib bed. The segmental vessels at the levels above and below the involved vertebral body are isolated and divided. After level verification, the intervertebral discs above and below the involved level are incised and removed with a combination of curets and rongeurs. It often is necessary to remove the rib head in order to identify the pedicle of the vertebral body. The pedicle is an important landmark, because it allows the surgeon to identify the posterior aspect of the vertebral body and the location of the spinal canal. After removal of the discs above and below, as well as the rib head, the vertebral body itself can be removed. Again, in most cases the only possible resection is an intralesional resection; however, there are occasions when a marginal resection is possible, depending on the location of the tumor in the vertebra. Behind the disc space, the posterior longitudinal ligament is rather thick and offers some protection for the spinal canal. Behind the vertebral body, however, the posterior longitudinal ligament is thin and narrow, and offers little resistance to central extrusion of tumor tissue or bone fragments against the spinal cord. As the surgeon approaches the dorsal third of the vertebral body and, therefore, the spinal canal, great care must be taken to remove debris of tumor and bone without in any way increasing the already existing impingement on the spinal canal. An angled curet, usually the most effective instrument, allows material to be pulled forward out of the canal and away from the dura mater.

The upper part of the thoracic spine from the first to the third thoracic vertebrae can be exposed using a thoracoplasty approach by mobilizing the scapula ventrally and resecting the second rib. As described by Harrington, the major advantage of the ventral approach is the surgeon’s ability to resect the tumor directly, decompress the neurologic structures from the side of their compromise, and “jack” open the collapsed vertebral space, thereby correcting the typical kyphotic deformity at its source.27,28

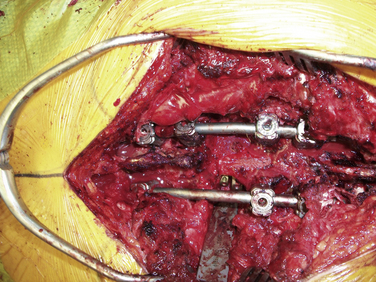

Dorsolateral Approach

A significant number of patients with spinal tumors require both ventral and dorsal decompression, as well as a ventral and dorsal stabilization. These patients often are poor candidates for a surgery that would involve two independent surgical approaches. To avoid this, a dorsolateral approach may be considered. The procedure can be performed from a single dorsolateral costotransversectomy approach, which enables a ventral and dorsal decompression, as well as segmental dorsal fixation, through a single incision. This dorsolateral approach is particularly useful for lesions in the upper thoracic spine, a difficult area to reach from a ventral thoracotomy or sternal splitting approach. The dorsolateral approach also is useful at the thoracolumbar junction, where a ventral approach necessitates taking down the diaphragm. This approach is particularly advantageous in the morbidly obese patient (see case example in Fig. 113-4).

The surgeon approaches the spine through a dorsal incision. The paraspinal muscles are elevated off of the dorsal elements. The spine itself is exposed out to the tips of the transverse process. The surgeon then identifies the rib as it passes deep to the transverse processes. The ribs at the level of interest as well as a level above and below are exposed through lateral retraction of the paraspinal musculature. Using electrocautery as well as a periosteal elevator, the rib at the level of interest is dissected free of the intercostal musculature and pleura. The rib is transected using a rongeur. The medial portion of the rib is followed in a subperiosteal fashion. Once the rib is believed to be adequately freed of its plural attachments, it is disarticulated from the transverse process and vertebral body. It sometimes is useful to resect the transverse process before removing the rib head. Bleeding may be encountered in this area, and should be controlled with electrocautery or an agent such as thrombin-soaked hemostatic gelatin (Gelfoam). The lateral aspect of the vertebral body may be further dissected using a periosteal elevator, such as a no. 1 Penfield dissector. A malleable retractor or a custom osteotomy retractor may be inserted to protect the underlying pleural and mediastinal structures. An exposure of this type typically allows the surgeon to approach half of the vertebral body. Bilateral exposures would facilitate the removal of the rest of the vertebral body. This approach may be combined with more extensive dorsal decompressions to perform a resection of the entire vertebra. This resection is, however, an intralesional resection and rarely is curative.

In addition, care should be taken during this approach to avoid injury to the underlying plural structures. If the pleura is violated, a chest tube may be placed at a remote site after the completion of the surgery or, more commonly, the chest tube may be placed into the pleural rent and wound bed during closure. To protect the spinal cord from ischemia, it is recommended that the patient’s mean arterial pressure be kept at greater than 65 mm. Conversely, for patients who have already failed radiation treatment, such a dorsal approach invites a high risk of wound dehiscence and infection. Because a significant amount of bone and ligament is removed, the patient is extremely unstable and would be unable to tolerate hardware removal. If an infection develops, antibiotic suppression is the most advisable form of treatment. Figures 113-4 and 113-5 show radiographic and clinical photographs of this technique.

Early results of dorsolateral approaches were reported by Dewald et al.,13 who found that only one of five patients regained ambulatory status and that patient survival was less than 6 months. Later, Bridwell et al. found that 60% of neurologically compromised patients improved postoperatively, although they were not satisfied with their ability to thoroughly decompress the spinal cord.29 More recently, Mülbauer et al.30 reported that 82% of patients improved neurologically and that 70% of previously nonambulatory patients were able to walk postoperatively.

Complications

Sundaresan et al. reported that complication rates may be as high as 48% following tumor resection.9 The complication rate was statistically higher for patients over the age of 65, those who had had prior treatment, and those with neurologic symptoms. Multiple series have found that the risk of complications is highest in previously radiated regions, because these tissues tend to be more susceptible to wound breakdown and infection.9,26 Previously radiated tissues tend to be more friable. Significantly higher blood loss may be noted in these regions. As stated earlier, many of these tumor resections are intralesional. It may be assumed that, were patients to survive long enough, a recurrence might occur. Construct failures are another significant concern, because these patients often are malnourished and have undergone radiation therapy. Despite this, the reported failure rates have been quite low, with Bridwell reporting hardware loosening in only 1 of 25 patients29 (4.0%) and Bauer reporting loosening in 3 of 67 patients (4.4%).26

Kostuik J.P., Errico T.J., Gleason T.F., Errico C.C. Spinal stabilization of vertebral column tumors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988;13(3):250-256.

Nicholls P.J., Jarecky T.W. The value of posterior decompression by laminectomy for malignant tumors of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;201:210-213.

Sundaresan N., Sachdev V.P., Holland J.F., et al. Surgical treatment of spinal cord compression from epidural metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(9):2330-2335.

Tokuhashi Y., Matsuzaki H., Toriyama S., et al. Scoring system for the preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990;15(11):1110-1113.

Weinstein J.N. Surgical approach to spine tumors. Orthopedics. 1989;12(6):897-905.

1. Dreghorn C.R., Newman R.J., Hardy G.J., Dickson R.A. Primary tumors of the axial skeleton. Experience of the Leeds Regional Bone Tumor Registry. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990;15(2):137-140.

2. Jaffe H.L. Tumors and tumorous conditions of the bones and joints. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1958.

3. Weinstein J.N., McLain R.F. Primary tumors of the spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1987;12(9):843-851.

4. White A.P., Kwon B.K., Lindskog D.M. Metastatic disease of the spine. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(11):587-598.

5. Wise J.J., Fischgrund J.S., Herkowitz H.N., et al. Complication, survival rates, and risk factors of surgery for metastatic disease of the spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24(18):1943-1951.

6. Tokuhashi Y., Matsuzaki H., Toriyama S., et al. Scoring system for the preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990;15(11):1110-1113.

7. Weinstein J.N. Surgical approach to spine tumors. Orthopedics. 1989;12(6):897-905.

8. Chan P., Boriani S., Fourney D.R., et al. An assessment of the reliability of the Enneking and Weinstein-Boriani-Biagini classifications for staging of primary spinal tumors by the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(4):384-391.

9. Sundaresan N., Sachdev V.P., Holland J.F., et al. Surgical treatment of spinal cord compression from epidural metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(9):2330-2335.

10. Tomita K., Kawahara N., Kobayashi T., et al. Surgical strategy for spinal metastases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(3):298-306.

11. Babat L.B., McLain R.F. Metastatic disease of the thoracolumbar spine. In: Mc Lain R.F., editor. Cancer in the spine. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2006:255-264.

12. Kostuik J.P., Errico T.J., Gleason T.F., Errico C.C. Spinal stabilization of vertebral column tumors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988;13(3):250-256.

13. DeWald R.L., Bridwell K.H., Prodromas C., Rodts M.F. Reconstructive spinal surgery as palliation for metastatic malignancies of the spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1985;10(1):21-26.

14. Murphy K.J., Deramond H. Percutaneous vertebroplasty in benign and malignant disease. Neuroimaging Clin North Am. 2000;10(3):535-545.

15. Dimar J.R.2nd, Voor M.J., Zhang Y.M., Glassman S.D. A human cadaver model for determination of pathologic fracture threshold resulting from tumorous destruction of the vertebral body. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23(11):1209-1214.

16. Hall A.J., Mackay N.N. The results of laminectomy for compression of the cord or cauda equina by extradural malignant tumour. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1973;55(3):497-505.

17. Siegal T., Tiqva P., Siegal T. Vertebral body resection for epidural compression by malignant tumors. Results of forty-seven consecutive operative procedures. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1985;67(3):375-382.

18. Gilbert R.W., Kim J.H., Posner J.B. Epidural spinal cord compression from metastatic tumor: diagnosis and treatment. Ann Neurol. 1978;3(1):40-51.

19. Weinstein J.N., Kostuik J.P. Differential diagnosis and surgical treatment of metastatic spine tumors. Frymoyer J.W., editor. The adult spine: principles and practice. New York: Raven Press. 1991;vol 2:861-888.

20. Riley L.H.3rd, Frassica D.A., Kostuik J.P., Frassica F.J. Metastatic disease to the spine: diagnosis and treatment. Instr Course Lect. 2000;49:471-477.

21. Onimus M., Papin P., Gangloff S. Results of surgical treatment of spinal thoracic and lumbar metastases. Eur Spine J. 1996;5(6):407-411.

22. Katagiri H., Takahashi M., Inagaki J., et al. Clinical results of nonsurgical treatment for spinal metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42(5):1127-1132.

23. Sundaresan N., Rothman A., Manhart K., Kelliher K. Surgery for solitary metastases of the spine: rationale and results of treatment. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(16):1802-1806.

24. Patchell R.A., Tibbs P.A., Regine W.F., et al. Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9486):643-648.

25. Nicholls P.J., Jarecky T.W. The value of posterior decompression by laminectomy for malignant tumors of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;201:210-213.

26. Bauer H.C. Posterior decompression and stabilization for spinal metastases. Analysis of sixty-seven consecutive patients. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1997;79(4):514-522.

27. Harrington K.D. Metastatic disease of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1986;68(7):1110-1115.

28. Harrington K.D. Anterior decompression and stabilization of the spine as a treatment for vertebral collapse and spinal cord compression from metastatic malignancy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;233:177-197.

29. Bridwell K.H., Jenny A.B., Saul T., et al. Posterior segmental spinal instrumentation (PSSI) with posterolateral decompression and debulking for metastatic thoracic and lumbar spine disease. Limitations of the technique. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988;13(12):1383-1394.

30. Mühlbauer M., Pfisterer W., Eyb R., Knosp E. Noncontiguous spinal metastases and plasmocytomas should be operated on through a single posterior midline approach, and circumferential decompression should be performed with individualized reconstruction. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000;142(11):1219-1230.