121 Third Trimester Pregnancy Emergencies

• Preeclampsia, a disease of the third trimester of pregnancy, is characterized by a sustained elevation in blood pressure and proteinuria. Edema is common in patients with preeclampsia but is no longer considered to be necessary for the diagnosis.

• HELLP syndrome is a particularly severe form of preeclampsia associated with high maternal morbidity and characterized by hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet counts.

• Eclampsia is defined by seizures, usually in the setting of preeclampsia.

• In patients with severe preeclampsia and eclampsia, basic management involves support of maternal vital signs, control of hypertension, prevention and treatment of seizure activity, and close consultation with obstetrics colleagues to determine the appropriate disposition.

• Placental abruption and placenta previa are the most serious causes of vaginal bleeding in late pregnancy.

• Painful bleeding in late pregnancy is probably due to placental abruption. In contrast, when the vaginal bleeding is painless, the cause is more likely to be placenta previa.

• Ultrasound evaluation of third trimester bleeding is diagnostic for placenta previa, but placental abruption is diagnosed clinically because ultrasound detects only 25% to 50% of abruptions.

• Treatment of third trimester bleeding includes stabilization of the patient, assessment of fetal status with ultrasound and fetal monitoring, and consultation with obstetrics colleagues to determine the need for delivery.

Preeclampsia and Eclampsia

Epidemiology

First pregnancies are at greatest risk. Other risk factors include extremes of reproductive age, more than 10 years between pregnancies, multiple gestations, molar pregnancies, previous or family history of preeclampsia, underlying diseases (hypertension, diabetes, autoimmune or renal diseases, obesity), and thrombophilia (e.g., antiphospholipid syndrome, factor V Leiden deficiency, activated protein C resistance).1

Pathophysiology

Preeclampsia is a multisystem disorder of gestation. Its exact cause is unclear and several mechanisms have been implicated. The disease is thought to originate within the placenta, which for reasons that remain obscure, has inappropriately decreased perfusion. Hypoperfusion and multiorgan effects ensue in some patients as a result of decreased intravascular volume and endothelial vascular leakage causing increased interstitial volume, interstitial protein leakage, and vasoconstriction.2 Preeclampsia affects nearly every organ system.

Preeclampsia has long-term implications for the health of these patients. After delivery, women with preeclampsia are at increased risk for the development of chronic hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and psychosomatic disorders.3

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Patients with severe preeclampsia may have additional symptoms of organ involvement (Box 121.1),4 including significant edema, especially facial edema, and documented weight gain of more than 5 pounds per week. Findings ominous for severe preeclampsia include a blood pressure of 160 mm Hg systolic and 110 mm Hg diastolic or greater, visual disturbances (blurred vision or scotomata), severe headache, altered mental status, seizures (which defines eclampsia), hyperreflexia with clonus, severe epigastric or right upper quadrant pain on examination, retinal hemorrhage with exudates and papilledema (which is rare and more commonly indicates underlying chronic hypertension), bibasilar rales and evidence of frank pulmonary edema, oliguria, and petechiae and bleeding from puncture sites.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The current classification of hypertension in pregnancy is divided into four categories: preeclampsia, gestational or transient hypertension, chronic hypertension, and preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension (Box 121.2).5 In addition, occult renal disease can be manifested as proteinuria and associated hypertension.

Box 121.2 Classification of Hypertension in Pregnancy

The differential diagnosis of severe preeclampsia is broad and distinction may be difficult, particularly with concomitant HELLP syndrome.6 Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and preeclampsia can have identical findings of thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, renal disease, and neurologic abnormalities. In patients with preeclampsia, the hypertension, proteinuria, and edema tend to precede the hematologic findings. In patients with TTP, they generally follow and are a result of the hematologic abnormalities. However, by the time that the patient arrives in the ED, these subtle distinctions may be almost impossible to delineate.

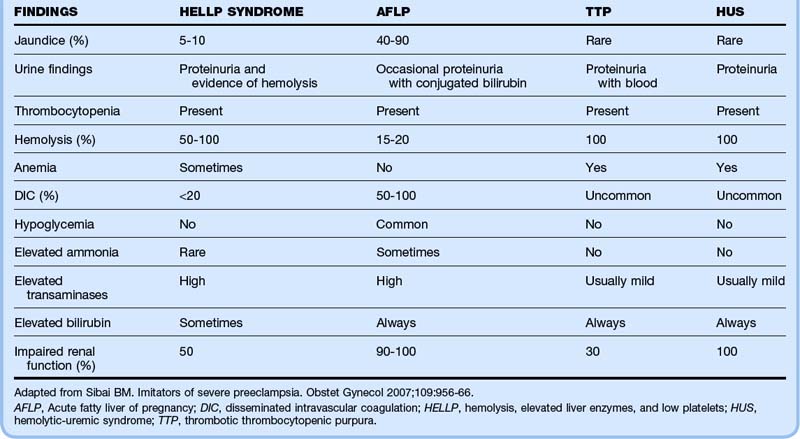

HELLP syndrome is characterized by peripheral smears showing schistocytes and burr cells, elevated LDH levels (>600 U/L), elevated liver enzymes (bilirubin >1.2 and aspartate transaminase >70 U/L), and low platelet count (<100,000).7 In addition, the abnormal laboratory test results in patients with HELLP syndrome can be seen in the other diseases noted in Box 121.3.

Box 121.3 Differential Diagnosis of Severe Preeclampsia with HELLP Syndrome

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura

HELLP, Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets.

Table 121.1 shows the frequency of certain signs and laboratory values that may help distinguish between several of the key conditions that mimic severe preeclampsia with HELLP syndrome.6

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Preeclampsia and Eclampsia

Pain with a firm painful uterus suggests placental abruption, which is a complication in up to 10% of preeclamptic pregnancies.

Diagnosing preeclampsia may be difficult in patients with chronic hypertension complicated by chronic renal disease.

Seizures in pregnant patients do not always herald eclampsia, and other structural, toxic, and metabolic causes should be considered.

Both thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and preeclampsia can have the identical findings of thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, renal disease, and neurologic abnormalities. In patients with preeclampsia, the hypertension, proteinuria, and edema tend to precede the hematologic findings, and in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, they generally follow and are a result of the hematologic abnormalities.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Preeclampsia and Eclampsia

Pregnant women being evaluated should have their blood pressure documented; any elevation needs to be addressed. A complete history should include symptomatic clues (e.g., headache, vision changes, abdominal pain) identifying causes of the elevation.

Review of records may indicate that the elevation is chronic and that the patient is being monitored for this finding.

If the blood pressure is not dangerously high and no other evidence of preeclampsia is present, it may be addressed by making arrangements for close outpatient follow-up.

Documentation should include completion of appropriate laboratory testing.

Patients with severe preeclampsia and eclampsia require documentation of all actions taken, interventions given, consultations requested, and the time at which all were ordered.

Treatment

It is important to differentiate between mild and severe preeclampsia8 (Table 121.2) when discussing the patient with the obstetrics consultant because acute management depends on the severity of disease, as well as fetal maturity. Recent research favors delivery over observation for gestational age older than 36 weeks.9

Table 121.2 Comparison of Symptoms of Severe and Mild Preeclampsia

| MILD | SEVERE | |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 140-150/90-100 mm Hg | >160/110 mm Hg |

| Proteinuria | 1+ | >3+ |

| Oliguria | Absent | Present |

| Visual disturbances, particularly scotomata | Absent | Present |

| Epigastric pain | Absent | Present |

| Headache | Absent | Present |

| Pulmonary edema or cyanosis | Absent | Present |

| Seizures (eclampsia) | Absent | Present |

| Laboratory test abnormalities (elevated creatinine and liver enzymes; thrombocytopenia) | Absent | Present |

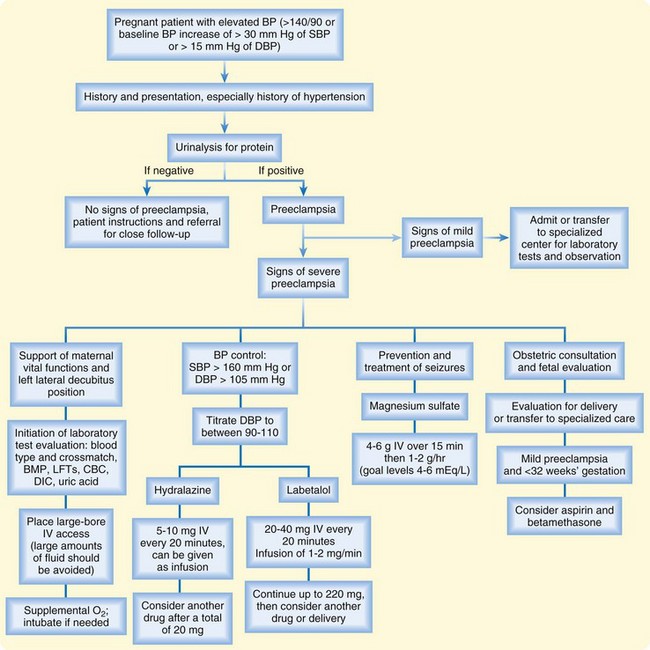

In patients with severe preeclampsia and eclampsia, basic management involves the following measures: (1) support of maternal vital functions and initiation of laboratory test evaluation, (2) control of severe hypertension, (3) prevention and treatment of seizures, and (4) early consultation for determination of final treatment (capability of the hospital to deliver material and fetal care, decision regarding immediate delivery).10

In preeclamptic patients, the mainstay of treatment is administration of magnesium for seizure prophylaxis when diastolic blood pressure exceeds 100 mm Hg. Magnesium is superior to phenytoin (Dilantin) or diazepam for prevention of eclamptic seizures.11 The recommended dosage is 4 to 6 g of magnesium administered intravenously over a 15-minute period, followed by a maintenance infusion of 1 to 2 g/hr, with a goal of serum levels of 4 to 6 mEq/L. The maintenance dosing should be started only if the patient still has patellar reflexes and an adequate respiratory rate. Magnesium should be used cautiously in patients with renal insufficiency or oliguria.

When systolic blood pressure reaches 160 mm Hg or diastolic pressure reaches 105 mm Hg, most experts recommend the use of an antihypertensive agent. The ideal antihypertensive agent for preeclampsia is one that reduces blood pressure in a controlled manner and has minimal side effects (Table 121.3).12,13 The exact degree of reduction is controversial, but it is reasonable to maintain diastolic blood pressure between 90 and 110 mm Hg.

Table 121.3 Priority Medications for Preeclampsia: Antihypertensive Agents

| DRUG | DOSAGE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Hydralazine | 5-10 mg IV q20min; consider another drug after a total of 20 mg; can be given as infusion | Side effects include tachycardia, nausea, vomiting, headache, epigastric pain |

| Labetalol | 20-40 mg IV q20min; continue up to 220 mg; give 1-2 mg/min as an infusion or repeat IV doses q3h | Side effects include flushing, orthostatic hypotension, tremulousness; do not use in patients with asthma or heart failure |

| Nifedipine | 10 mg sublingually; response time is 10 min, with maximum effect at 30 min; if no response after 20 mg, consider alternatives | Third-line treatment; avoid in older patients or those with a family or personal history of coronary disease, especially if smokers; may cause a precipitous decrease in blood pressure, especially when used with magnesium |

| Clonidine | 0.1 mg PO in 30 min, then 0.1 mg every hour | Third-line treatment; no parenteral form; not good for initial management |

Labetalol, a combination α- and β-adrenergic blocking agent, is another commonly used medication, and some authors prefer this agent over hydralazine.14 The dose is 20 to 40 mg administered as a slow IV push every 20 to 30 minutes. This can be followed by 1 to 2 mg/min given by continuous infusion or by IV dosing every 3 hours after the blood pressure has been controlled. Side effects include flushing, orthostatic hypotension, and tremulousness. Labetalol should not be used in patients with asthma or evidence of heart failure.

Other antihypertensive agents to avoid include sodium nitroprusside and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Sodium nitroprusside should be used only as a last resort because fetal cyanide poisoning has been reported in animal studies.15 However, if the blood pressure is not responding to other agents, use of this medication is appropriate. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors have been shown to cause fetal death in animals and possibly renal failure in neonates and thus should not be used in pregnancy. Clonidine and α-methyldopa are not administered parenterally and are therefore rarely used in initial management of preeclampsia.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

In pregnant women evaluated in the ED for any complaint, blood pressure should be considered carefully. Mild preeclampsia may progress rapidly to severe preeclampsia with little warning. If a pregnant patient is found to have elevated blood pressure, the initial assessment should include a complete history and physical examination with attempts to determine whether the elevated blood pressure is new or old and whether other evidence of preeclampsia is present (Fig. 121.1). If there is concern that the elevated blood pressure indicates preeclampsia, the patient will usually need admission for close monitoring and therapy.

Third Trimester Bleeding

Epidemiology

Vaginal bleeding occurs in about 3% to 4% of second and third trimester pregnancies. It can herald catastrophic problems for both the mother and fetus.16 Placental abruption and placenta previa are the most serious causes of vaginal bleeding in late pregnancy. In 20% of women the bleeding is due to placenta previa, and in 33% it is due to placental abruption. Placental abruption is estimated to occur in about 1% of all pregnancies. Of these pregnancies, 20% to 40% will be associated with perinatal morbidity or mortality involving the mother or fetus. Maternal death, though diminishing in incidence (0.03% of pregnant women), remains significant.17 Additionally, women who sustain trauma in pregnancy are at risk for abruption, even when the trauma appears to be minimal.

Pathophysiology

Placental Abruption

Risk factors for placental abruption include previous placental abruption, cocaine use, smoking, hypertension in pregnancy (preeclampsia, gestational or chronic hypertension), trauma, advanced maternal age, multiparity, and multiple gestation. Other risk factors are fetal malformation, premature rupture of membranes, uterine leiomyomas, previous cesarean section, and malnutrition.17

Major trauma, as well as seemingly insignificant trauma, is an important cause of placental abruption. Because pregnant trauma patients are initially managed in the ED, the emergency physician should be vigilant for signs of placental abruption. Abruption may be seen in up to 30% of patients with severe abdominal trauma and in up to 3% with minor trauma in late pregnancy.18,19

Placenta Previa

Painful bleeding in late pregnancy is probably due to placental abruption; however, when the vaginal bleeding is painless, the cause is more likely to be placenta previa, with the placenta being located either partially or completely over the cervical os.16,20 In preparation for labor, softening of the lower uterine segment and effacement of the cervix tear the implanted placenta previa, which results in painless vaginal bleeding. Only 10% of women have contractions or uterine tenderness coincident with the initial vaginal bleeding. Many women have brief painless bleeding initially, which is a warning that placenta previa is present. As the cervix dilates further, the bleeding can become rapid and life-threatening.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

In contrast to placental abruption, the classic finding in patients with placenta previa is painless bleeding.16 The bleeding varies from mild to massive and from intermittent to continuous. Bleeding usually occurs after the 28th week of gestation.

Tips and Tricks

Third Trimester Bleeding

Do not perform a speculum examination in patients with third trimester bleeding.

Major trauma, as well as seemingly insignificant trauma, is an important cause of placental abruption.

All vaginal bleeding during the third trimester should be considered serious; investigation for other causes of the vaginal bleeding should be delayed until the diagnosis of placenta previa or placental abruption is ruled out.

Focus on maternal stabilization—when mom does well, the fetus has a better chance to do well.

Diagnosis of placental abruption is based on clinical signs; the diagnosis should always be considered in pregnant women seen in the ED with significant uterine contractions and fetal distress.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Following clinical examination, ultrasound imaging may be performed, which may result in another diagnosis in 25% to 50% of cases (Box 121.4). About 10% of pregnant patients with abdominal pain and bleeding may have preterm labor, heavy bloody show with the onset of labor, or marginal placental or subchorionic bleeding. These patients should be admitted for monitoring. Other causes of vaginal bleeding are vaginal or cervical polyps, cervical lacerations or erosions, cervical carcinoma, and vulvar injury.

Diagnostic Testing

In patients with third trimester bleeding, ultrasonography may be performed to rule out placenta previa, to determine fetal age and viability, and to look for placental abruption. However, only 25% to 50% of placental abruptions are identified on ultrasound, and the appearance may be unimpressive because the clot looks similar to the placenta. When abruption is seen on ultrasound, its specificity is 95%.21 The diagnosis of placental abruption is clinical, and the emergency physician should suspect placental abruption in a pregnant woman with significant uterine contractions and fetal distress. Monitoring of the fetal heart rate and uterine contraction (tocography) should be initiated early. The diagnosis is confirmed by examination of the placenta after delivery.

In trauma patients with abdominal pain in late pregnancy, other injuries must be considered and are best managed by a multispecialty team consisting of emergency medicine, trauma, and obstetrics. Early evaluation with focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST), as well as assessment of fetal size (for dates) and fetal heart rate, is key. Chest and pelvis radiographs, as well as computed tomography (CT) scans, may be necessary. Though not the test of choice for abruption, abdominal CT scans have a sensitivity of 50% to 100%, depending on the expertise of the radiologist.22 During the evaluation it is important that the fetus be monitored continuously as early as possible. Resuscitation of the mother is the best treatment for the fetus. If the mother has loss of vital signs, perimortem cesarean section should be considered. See Chapter 11, Resuscitation in Pregnancy, Chapter 79, Blunt Abdominal Trauma, and Chapter 122, Emergency Delivery and Peripartum Emergencies, for further details.

Laboratory evaluation includes a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic profile, PT and PTT, DIC panel (fibrinogen, fibrin split products), urinalysis, and blood type and crossmatch. Anemia is a concern with both placental abruption and placenta previa. Because DIC can complicate placental abruption, it is important to perform the relevant tests. The Kleihauer-Betke test, which confirms the presence of fetal blood cells in the maternal circulation, may be performed if fetal-maternal transfusion is suspected. It is neither sensitive nor specific for abruption but quantifies that volume of fetal-to-maternal transfusion if positive.17–19

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Third Trimester Bleeding

Vital signs of the patient, as well as fetal monitoring

Size of the gravid uterus and the degree of uterine spasm as determined during the physical examination

Presence or absence of vaginal bleeding and its onset, quantity, and duration

Events before the onset of bleeding

Type and time of interventions, as well the time when consultation was requested

Personal and family history with a focus on risk for placental abruption

Medical (including obstetric) history, especially in regard to cesarean section

Treatment

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Third Trimester Bleeding

Hypertension not only increases the risk for placental abruption but also predisposes to more severe placental abruption and increased fetal mortality.

Although vaginal bleeding occurs in 80% of cases of placental abruption, some abruptions are concealed, with no evidence of overt bleeding.

Placental abruption in patients seen in the emergency department may be the result of abuse.

Many women with vaginal bleeding will have brief painless bleeding initially; this is a sign of placenta previa.

Oxford CM, Ludmir J. Trauma in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52:611–629.

Shah DM. Preeclampsia: new insights. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2007;16:213–220.

Sibai BM. Imitators of severe preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:956–966.

Sinha P, Kuruba N. Ante-partum haemorrhage: an update. J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;28:377–381.

Vidaeff AC, Carroll MA, Ramin SM. Acute hypertensive emergencies in pregnancy. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(10 Suppl):S307–S312.

1 Duckitt K, Harrington D. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia at antenatal booking: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ. 2005;330:565.

2 Shah DM. Preeclampsia: new insights. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2007;16:213–220.

3 Van Pampus MG. Long-term outcomes after preeclampsia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48:489–494.

4 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group Report on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1691–1712.

5 Norwitz ER, Hsu CD, Repke JT. Acute complications of preeclampsia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:308–329.

6 Sibai BM. Imitators of severe preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:956–966.

7 Baxter JK, Weinstein L. HELLP syndrome: the state of the art. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59:838–845.

8 O’Brien JM, Barton JR. Controversies with the diagnosis and management of HELLP syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48:460–477.

9 Kooopmans CM, Bijlenga D, Groen H, et al. Induction of labour versus expectant monitoring for gestational hypertension or mild pre-eclampsia after 36 weeks’ gestation (HYPITAT): a multicentre, open label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:979–988.

10 Duley L, Meher EA. Management of pre-eclampsia. BMJ. 2006;332:463–468.

11 Euser AG, Cipolla MJ. Magnesium sulfate for the treatment of eclampsia. Stroke. 2009;40:1169–1175.

12 Roberts JM, Gammill HS. Preeclampsia: recent insights. Hypertension. 2005;46:1243–1249.

13 Vidaeff AC, Carroll MA, Ramin SM. Acute hypertensive emergencies in pregnancy. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(10 Suppl):S307–S312.

14 Aagaard-Tillery KM, Belfort MA. Eclampsia: morbidity, mortality, and management. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48:12–23.

15 Briggs GG. Drug effects on the fetus and breast-fed infant. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:6–21.

16 Sinha P, Kuruba N. Ante-partum haemorrhage: an update. J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;28:377–381.

17 Oyelese Y, Ananth CV. Placental abruption. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1005–1016.

18 Brown HL. Trauma in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:147–160.

19 Oxford CM, Ludmir J. Trauma in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52:611–629.

20 Oyelese Y, Smulian JC. Placenta previa, placenta accreta, and vasa previa. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:927–941.

21 Glantz C, Purnell L. Clinical utility of sonography in the diagnosis and treatment of placental abruption. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:837–840.

22 Wei SH, Helmy M, Cohen AJ. CT evaluation of placental abruption in pregnant trauma patients. Emerg Radiol. 2009;16:365–373.