189 Thermal Burns

• Many patients who initially appear to have a mild airway burn injury still require early intubation because critical edema will develop. Intubate; do not observe.

• Extremely high doses of narcotics (three to five times normal) are usually required to control pain in patients with severe burns.

• Patients with severe burns have large fluid requirements, which are best determined initially by standard calculations.

• The best measure of adequate fluid replacement is urine output.

• Cold water can help relieve the pain of first- and second-degree burns, but patients with significant burns involving more than 9% of their total body surface area should not have cold applied.

• Burn centers have improved mortality rates, so transfer to a burn center should be considered early in the patient’s management.

• Empiric oral or intravenous antibiotic administration is not indicated, but topical antibiotics are.

Epidemiology

Approximately 500,000 patients sustain nonfatal burn injuries in the United States each year.1 Only 6% of these patients require hospitalization, so most are treated as outpatients.

Pathophysiology

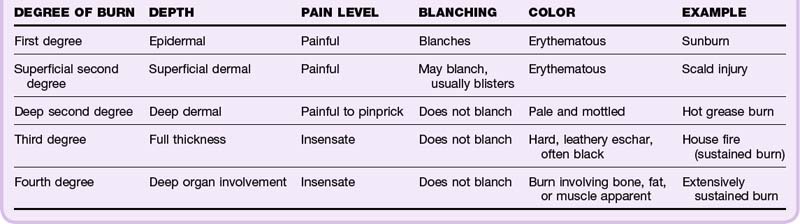

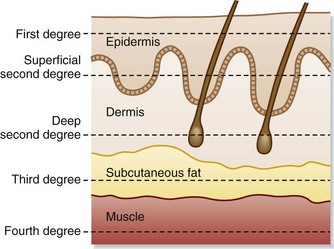

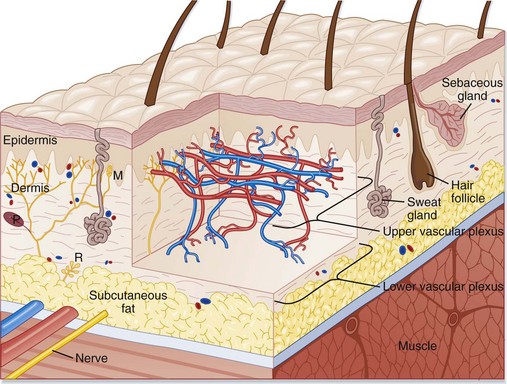

Knowing the anatomy of the skin is essential to understanding burn pathophysiology (Fig. 189.1). Burns are classified according to the depth of injury (Table 189.1 and Fig. 189.2). First- and second-degree burns are partial-thickness burns and have a better prognosis. Full-thickness burns (third and fourth degree) are insensate and require skin grafts (unless <1 cm) or reconstruction because of destruction of the epidermis and dermis. Based on the depth of the burn, the ability to heal can be predicted. Because the dermis itself is the living tissue, the depth of burn into the dermis determines how likely wounds are to heal and what degree of scarring can be expected.

Fig. 189.1 Schematic representation of a cross section of human skin.

(From Adkinson NF, Yunginger JW, Busse WW, et al, editors. Middleton’s allergy: principles and practice. 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2003.)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Frequently, occupational exposure causes burns. Direct contact with flame, scalds, injuries caused by heated equipment or arc welding, gasoline fires, and cooking accidents are all common. In children or elderly patients with burn injuries, the concern for abuse is always present (see the “Red Flags” box).

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Burns inconsistent with the mechanism: concerning for nonaccidental trauma or abuse

Circular burns consistent with cigarette butt burns

Burns on the lower extremities without burns on the soles: consistent with forced immersion scald burns

Any perineal burn (area not exposed during normal activities)

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

In each patient with a burn, the airway is still the most important component. Burn victims are often also subject to smoke inhalation or thermal injury to respiratory tissue from superheated air, and these injuries take priority over any others. Carbon monoxide, cyanide, and other inhaled toxins should be considered. The most threatening injuries are deep burns, burns covering a significant proportion of body surface area, and respiratory burns (Box 189.1).

Box 189.1

Criteria of the American Burn Association for Referral to a Burn Unit

Partial-thickness burns involving greater than 10% total body surface area

Burns that involve the hands, face, feet, genitalia, perineum, or major joints

Third-degree (full-thickness) burns in any age group

Electrical burns, including lightning injury

Burn injury in patients with preexisting medical disorders that could complicate management or recovery or could affect mortality

Patients with concomitant burn injury and trauma in which the burn injury poses the greatest risk for morbidity or mortality

Burned children in hospitals without qualified personnel or equipment for the care of children

Burn injury in patients who require special social, emotional, or long-term rehabilitative intervention

Adapted from American Burn Association. Burn unit criteria. Available at http://www.ameriburn.org.

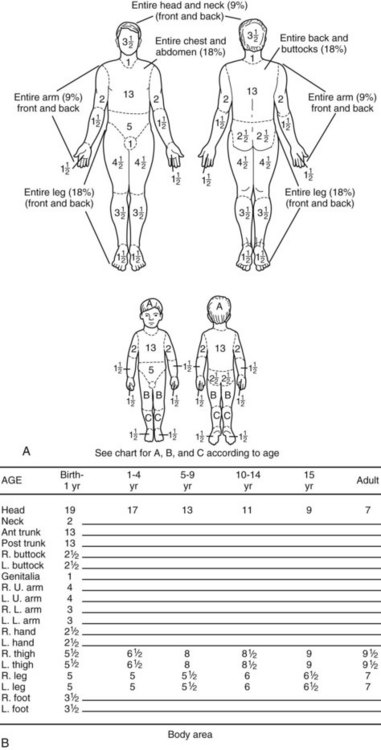

Aside from the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation), the most important aspect of burn assessment is estimation of burn depth and burn surface area. Burn depth can be assessed by evaluating the degree of blanching, noting the presence of blistering of the skin, and checking for the presence of pain. Total burn surface area is best assessed by using a Lund and Browder chart (Fig. 189.3). Alternatively, a patient’s palmar surface (not including the fingers) can be used as a crude measure of 1% of the patient’s body surface area.

Treatment

The first intervention for burn victims is assessment of the airway. Smoke inhalation is a common issue, so all patients who do not need immediate intubation should be given 100% humidified oxygen via a nonrebreather mask. Because edema can progress in minutes to hours and the full extent of respiratory damage may not become evident until 12 hours after the initial injury, patients with evidence of airway damage should be intubated prophylactically, before the airway becomes edematous (see the “Priority Actions” box).

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Address the patient’s respiratory status, with high suspicion for airway injury that will worsen; intubate if necessary, and supply supplemental oxygen otherwise.

Assess the size and depth of the burn injury.

Provide anesthesia and pain management. Patients may require extremely high doses of narcotics (three to five times normal).

Start appropriate fluid management and consider placement of a Foley catheter for assessment of fluid status.

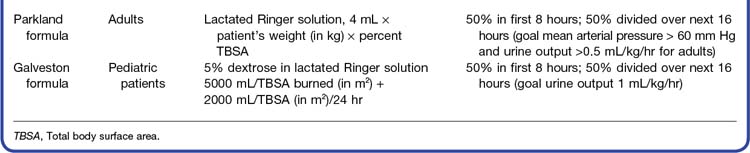

Fluid requirements are a key facet in the management of a burn patient. Two specific formulas are most commonly used. The Parkland formula is used to estimate fluid replacement in adults. This formula gives suggested fluid replacement in addition to maintenance fluid amounts over a 24-hour period; half of this fluid should be given over the first 8 hours, with the remaining half administered over the following 16 hours. The original Parkland formula used lactated Ringer solution as the fluid of choice.2

For children, the Galveston formula is recommended for calculation of fluid repletion. The Galveston formula suggests that lactated Ringer solution with 5% dextrose should be used as the fluid of choice because of the lack of glycogen stores in the pediatric population. Again, half of the total amount should be given in the first 8 hours, with the remainder administered within the next 16 hours. Maintenance fluid should be also added, and particular attention should be paid to maintaining body temperature (see the “Facts and Formulas” box).

Despite these formulas, fluid resuscitation is more accurately based on appropriate urine output, which is 0.5 mL/kg/hr in adults and up to 1 mL/kg/hr in children. When one is uncertain about the patient’s fluid status, as may occur with congestive heart failure or pulmonary edema, a Swan-Ganz catheter may be necessary to provide guidance. Some controversy exists about the optimal fluid to use in burn patients. Although current guidelines specify crystalloid only initially, more recent studies suggest a probable role for colloid solutions.3,4

All burns should be gently cleansed of debris with normal saline solution. Superficial burns (superficial second- and first-degree burns) should be dressed with topical antimicrobial dressings, with frequent dressing changes planned (every 6 hours). A degree of controversy exists about the best antimicrobial dressing. No clearly superior agent has been reported in the literature.5 One commonly used agent, silver sulfadiazine, should not be applied to the face because of concerns about staining. A good option, particularly for the face, is a simple, over-the-counter antibiotic ointment. For mild burns, aloe vera cream is also acceptable. Biosynthetic dressings are another option, but because of cost and availability, these dressings are usually limited to inpatient burn management. A recent study showed a combination of hyaluronic acid plus silver sulfadiazine to be superior to just silver sulfadiazine alone.5

Occasionally, a burn covers such a large area that it poses a risk for respiratory or vascular compromise. For example, a circumferential burn on an extremity can compromise the vascular supply to that extremity, whereas a nearly circumferential full-thickness burn on the chest can prevent chest movement and result in an inability to ventilate. Through escharotomies these constricting bands of tissue can be released (Table 189.2). The basic method of performing an escharotomy is to incise the constricting band of tissue down to subcutaneous fat. Fasciotomies for compartment syndrome may also be required with thermal burns that cause edema and subsequent increased compartmental pressure.

| TYPE OF ESCHAR | RECOGNITION | APPROACH |

|---|---|---|

| Chest eschar | Burn across the chest with difficulty expanding the chest, possible increased peak pressures if on a ventilator | Anesthetize and cut to subcutaneous fat on the chest in the anterior axillary lines from the clavicles to the inferior costal margins; connect these incisions superiorly and inferiorly, with possible other transverse incisions needed if ventilation is still not possible. |

| Extremity eschar | Burn of the extremity with vascular compromise in the extremity | Anesthetize and cut to subcutaneous fat on the medial and lateral sides of the extremity from 1 cm proximal to the eschar to 1 cm distal to the eschar, with care taken at sites where vascular or neurologic injury may occur. |

| Neck eschar | Circumferential burn of the neck | Anesthetize and cut to subcutaneous fat on the lateral and posterior aspects of the neck; avoid the carotid or jugular venous structures. |

| Penile eschar | Circumferential burn of the penis | Anesthetize and cut to subcutaneous fat on the midlateral portions of the penis; avoid the dorsal penile vein. |

| Hand eschar | Circumferential burn of the hand with evidence of vascular compromise | Anesthetize and cut to subcutaneous fat on the lateral side of each finger, the palmar crease, and between the metacarpals on the dorsum of the palm. |

| Abdominal wall eschar | Burn of the abdominal wall with evidence of increasing intraabdominal pressure (elevated bladder pressure) | Anesthetize and cut to subcutaneous fat on the lateral sides of the abdominal wall. |

Much discussion has centered around empiric antibiotic administration. No data support the empiric use of antibiotics for acute burn wounds, except in topical form, as recommended for superficial burn wounds.6

Tips and Tricks

Dressings

First, ensure adequate anesthesia.

Gently clean the wound with normal saline solution.

Assess the depth of each wound individually.

For superficial wounds, dress with a topical antibiotic and cover with gauze.

For deep wounds, consider burn unit referral, surgical débridement, or application of a dry dressing.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Patients with major burns should receive care in a specialized burn center (see Box 189.1). Minor burns can be cared for on an outpatient basis with close follow-up and instructions for assessing for infection. Patients should be informed of what to expect over the days and weeks following their burn (see the “Patient Teaching Tips” box). All patients with concern for possible nonaccidental burns should be evaluated by both social services and law enforcement, and patients with self-inflicted injuries should be referred for psychiatric care. Any pediatric patient suspected of suffering abuse should be admitted to the hospital, even if the burn itself does not meet admission criteria, so that social services can ensure the child’s safety (see the “Red Flags” box).

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Inform all burn patients about the remote possibility that the burn may worsen over the next 24 hours, with tissue death possibly requiring grafts.

After the first couple of days, a normal wound should exhibit consistently gradual improvement in pain, swelling, size, and tissue color.

Inform patients that a burn may result in a scar and probably will; the size and shape of the scar can be addressed by a plastic surgeon, who may need to perform a scar revision to obtain the desired cosmetic result.

If any of the foregoing situations develop, the patient should know to return to the emergency department or to follow up with specialty referral.

Assure patients that if they follow these instructions, additional steps can then be taken to optimize recovery.

Care of a partial-thickness burn: Check the burn every day for signs of infection, such as increased pain, redness, swelling, or pus. If you see any of these signs, go to your doctor right away. To prevent infection, avoid breaking blisters. Change the dressing every day. First, wash your hands with soap and water. Then gently wash the burn and put antibiotic ointment on it. If the burn area is small, a dressing may not be needed during the day.

Burned skin itches as it heals. Keep your fingernails cut short and do not scratch the burned skin. The burned area will be sensitive to sunlight for up to 1 year. Sunscreen has been shown to decrease how severe scars appear and should be used regularly.

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. Available at www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars

2 Pham T, Gibran N. Thermal and electrical injuries. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:185–206. vii-viii

3 Fodor L, Fodor A, Ramon Y, et al. Controversies in fluid resuscitation of burn management: literature review and our experience. Injury. 2006;37:374–379.

4 Cooper AB, Cohn SM, Zhang HS, et al. Five percent albumin for adult burn shock resuscitation: lack of effect on daily multiple organ dysfunction score. Transfusion. 2006;46:80–89.

5 Costagliola M, Agrosi M. Second degree burns: a comparative, multicenter, randomized trial of hyaluronic acid plus silver sulfadiazine vs. silver sulfadiazine alone. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1235–1240.

6 American College of Surgeons, Committee on Trauma. Resources for the optimal care of the injured patient. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 1999.