CHAPTER 2 Theoretical Foundations of Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics

What is the role of “theory” in the field of developmental-behavioral pediatrics? To answer this question, it is useful to imagine how clinical work and research endeavors would be affected if there were no theoretical or conceptual models to explain observed phenomena in practice or in research. Without conceptual models, practitioners would have no basis for suggesting specific interventions or understanding why some interventions are successful and why others fail. More to the point, practitioners would not be able to explain to families why certain recommendations are indicated or why the suggested interventions are likely to be helpful. In discussing nonadherence to treatments for chronic illness, Riekert and Drotar1 argued that conceptual models serve several purposes for the practitioner. Specifically, these models (1) guide the practitioner in the information gathering process, (2) guide communications between patients and practitioners, (3) aid the practitioner in determining the goals and targets of interventions, and (4) help the practitioner anticipate potential barriers to treatment success.

In the absence of theory, pediatricians may be inclined to develop new interventions for each specific physical condition and may assume that mechanisms that underlie certain difficulties are unique for each illness group. For example, without a general guiding theory, medical adherence issues for asthma may be treated entirely differently from medical adherence issues for type 1 diabetes. Alternatively, available developmentally oriented, family-based theories of medical adherence would indicate that similar processes underlie medical adherence across populations and that an intervention that works well for one illness may also work well for a different population. For example, on the basis of theory, a developmental-behavioral pediatrician may suggest that families make developmentally gauged changes in how responsibilities for adherence to aspects of the medical regimen are shared between parent and child, particularly as the child begins to transition into early adolescence.2

With theoretical frameworks, researchers would be more able to generate testable hypotheses or determine which variables are critical and should be examined in the context of their research programs. Indeed, a conceptual model facilitates the development of a program of research (as opposed to a set of unrelated studies), and it drives all aspects of the research endeavor, including participant selection, the design of the study, specification of independent and dependent variables, specification of relationships between variables, data-analytic strategies, and potential recommendations for clinical practice.1,3

The goal of this chapter is to demonstrate the importance of theory development and the role of conceptual models in the field of developmental-behavioral pediatrics. Throughout, we take the “developmental” aspect of developmental-behavioral pediatrics very seriously. Indeed, an exciting but also challenging aspect of studying and providing clinical services to children is that they are developmental “moving targets.” Moreover, the course of developmental change varies across individuals, so that two children who are the same age may differ dramatically with regard to neurological, physical, cognitive, emotional, and social functioning.4 For example, two 12-year-old boys may differ dramatically with regard to pubertal status, one boy being prepubertal and the other experiencing the latter stages of pubertal development; such interindividual differences have significant effects on their physical and social functioning. Similarly, consider two 9-year-old girls, one of whom is functioning at a lower level of cognitive ability. The child with more cognitive impairment may misinterpret social cues from her peers and fail to express her emotions verbally, which results in aggression with peers. The other 9-year-old child may respond to challenging social situations by questioning her peer and verbally expressing her feelings in a socially appropriate manner. It is also the case that the same behaviors that are developmentally normative at a younger age are often developmentally atypical at a later age.5 For example, temper tantrums may be an expected outcome when a young child lacks the language abilities to express his or her frustration. In older children, and after language skills develop, tantrums are expected to be less likely. Frequent tantrums in an older child would be considered atypical.

In attempting to understand better such developmental variation and change, theories have been advanced to explain both the general rules of development, as well as individual variation.6 In general, developmental-behavioral pediatricians may have the opportunity to educate primary care pediatricians, who would benefit greatly from attention to and extensive knowledge of the theory and research focused on these developmental issues. In their work, developmental-behavioral pediatricians have opportunities to observe the same children frequently and repeatedly over the course of individual development. Thus, if pediatricians are equipped with the proper knowledge, they are in a unique position to identify early risk factors that portend later, more serious difficulties. Moreover, they can intervene early while the difficulties are still manageable. They also have opportunities to follow up with these same children to determine whether a particular early intervention had a sustained and positive impact.

Since the appearance of a similar volume on developmental-behavioral pediatrics in the late 1990s,7 the field of developmental-behavioral pediatrics has witnessed extensive progress in theory development across several areas (e.g., biological bases of behavior, behavioral genetics and gene-environment interactions, developmental psychopathology). Concurrent with these developments, both the quantity and quality of research focused on such issues have increased as well. The purpose of this chapter is to review current theories relevant to the field of developmental-behavioral pediatrics. We begin with a discussion of “What makes a good theory?” in which we discuss features of theories that have had a major influence on the field. Second, we provide an historical perspective on theories in the field of developmental-behavioral pediatrics, followed by a discussion of more contemporary theoretical and empirical work. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of directions for future theory development.

WHAT MAKES A GOOD THEORY?

Before a discussion of components of useful theories, it is important to define our use of the term theory and to note similarities between our use of this term and other related terms, such as framework and model. A strict (but also ideal) definition of theory is as follows:8–10 “[A theory is] a set of interconnected statements-definitions, axioms, postulates, hypothetical constructs, intervening variables, laws, hypotheses… usually expressed in verbal or mathematical terms.…[The theory] should be internally consistent… testable and parsimonious… [and] not contradicted by scientific observations” (Miller, 1983, pp 3-4).11 In general, most scientific theories fall short of this ideal definition. For this book, we have chosen a “soft” definition of theory. In our view, a theory is a model or framework that guides clinical work or research endeavors. It could be considered a metaphor for how two or more variables are related or how a causal process is likely to unfold over time (e.g., a camera is a metaphor for how the human eye functions; such a metaphor could serve as a guide for future investigations of the eye). Despite their limitations, “soft” theories provide more guidance than if there were no theories. In the absence of theory, physicians would be forced to rely on past experience and common sense. However, as noted by Lilienfeld, the more widely held the belief is and the more that a belief is based on common sense (e.g., parents have more influence on children than children have on parents), the more crucial it is that such beliefs be carefully scrutinized and subjected to empirical evaluation.12

Clarity of Focus

Useful conceptual models are often focused on a phenomenon that is important to professionals working in the field and are very specific in their focus, rather than overly general. For example, suppose an investigator wanted to develop a model of communication between practitioner and patient. It would be tempting to include all possible variables in this model. With regard to the patient, the investigator could include variables such as past medical experiences, type of condition, temperament, communication style variables, personality variables, historical and family system variables, and variables that focus on beliefs and expectations. With regard to the practitioner, the investigator could include a similar number of variables. Although all of these variables may be relevant to the phenomenon of interest, inclusion of all relevant variables would make for a very unwieldy conceptual model. From the perspective of a practitioner, there would be too many variables to integrate, making it difficult to consider any one of them during an actual interaction with a patient. From a research perspective, the model would likely be highly exploratory and require “everything but the kitchen sink” data-analytic strategies. Findings based on such strategies would not necessarily be validated across research programs. Thus, a more focused model would be needed. Such a model would explain a smaller aspect of the phenomenon of interest, but it would probably have more clinical and research usefulness. Continuing with the example just given, the investigator might develop a model that proposes a typology of practitioner and patient communication styles that delineates the best fitting matches between different practitioner and patient communication styles.1

Developmental Emphasis

A developmental emphasis is crucial for the work of the developmental-behavioral pediatrician and should, therefore, be an integral part of any theoretical or conceptual model. At the most general level, a model is developmentally oriented if (1) it includes developmentally relevant constructs (which could be biological, cognitive, emotional, or social), (2) the constructs are tied to the age group under consideration, and (3) it emphasizes changes in the proposed constructs.11 Such a model also takes into account the critical developmental tasks and milestones relevant to a particular child’s or adolescent’s presenting problems (e.g., level of self-control, ability to regulate emotions, the development of autonomy, a child’s ability to share responsibilities for medical treatments with parents).

The Model Addresses Limitations of Previous Models and Research

A useful theory-driven model seeks to move the field forward by addressing gaps in prior theorizing.3 The process by which conceptual models are derived is often a cumulative process by which older conceptual models are integrated with new empirical findings to generate new conceptual models. For example, Thompson and Gustafson reviewed prior models of psychological adaptation to chronic illness.3 Older models13 specified important constructs of interest (e.g., stress, coping style, response to illness), but later models14,15 were more focused on identifying particular components of these constructs that were relevant (for an example involving palliative vs. adaptive coping and specific cognitive processes concerning illness appraisal and expectations, see Thompson and colleagues15). Later, these more focused models were refined in response to research findings and critiques16 (see Wallander et al for revised versions of these models17).

Specification of Independent Variables and Dependent Variables

Conceptual models rarely account completely for a medical phenomenon; thus, there is usually variance in the outcome that the predictors do not adequately explain. For example, in attempting to understand causes of spina bifida (a congenital birth defect that produces profound effects on neurological, orthopedic, urinary, cognitive/academic, and social functioning), investigators have recently determined that low levels of maternal folic acid before conception are causally related to the occurrence of spina bifida. Unfortunately, this single variable does not account for all cases of spina bifida. Thus, comprehensive models of causation for this condition often include other variables as well, including genetic and behavioral factors.

Articulation of Links between Independent Variables and Dependent Variables

Perhaps the most important aspect of a conceptual model is the articulation of links between the predictors and outcomes. Models vary considerably in their levels of sophistication; at the simplest level, main (or direct) effects of predictor on outcome (e.g., parenting behaviors→child adjustment) are proposed. As the number of predictors increases, scholars often seek to test multiple pathways between predictors and outcomes. Researchers who study pediatric populations have begun to posit more complex theoretical models to explain phenomena of interest. These models include longitudinal developmental pathways, mediational and moderational effects, genetic × environment interaction effects, risk and protective processes, and intervening cognitive variables (e.g., cognitive appraisal3). This enhancement of the theoretical base has necessitated an increase in terminological and data-analytic sophistication. Research focused on mediational and moderational models (and particularly the definitions of risk and protective factors) has emerged as a crucial method for testing competing theories about developmental pathways and other concepts central to developmental-behavioral pediatrics (see Rose et al for a more in-depth discussion18).

MEDIATOR

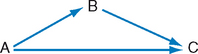

A mediator is an explanatory link in the relationship between two other variables (Fig. 2-1). Often a mediator variable is conceptualized as the mechanism through which one variable (i.e., the predictor) influences another variable (i.e., the criterion).17,19,20 Suppose, hypothetically, that a researcher finds that parental intrusive behavior is negatively associated with child adherence to a medical regimen. Given these findings, a researcher could explore whether a third variable (e.g., child independence) might account for or explain the relationship between these variables. Continuing with the example, suppose that child independence mediates the relationship between intrusiveness and adherence (more intrusive parenting→less child independence→less medical adherence). In this case, parental intrusiveness would have a negative effect on level of child independence, which in turn would contribute to poor medical adherence.21

FIGURE 2-1 Mediated relationship among variables. A, Predictor; B, mediator; C, criterion/outcome.

(From Rose BM, Holmbeck GN, Coakley RM, et al: Mediator and moderator effects in developmental and behavioral pediatric research. J Dev Behav Pediatr 25:1-10, 2004. Copyright 2004 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Reprinted with permission.)

MODERATOR

A moderator, unlike a mediator, is a variable that influences the strength or the direction of a relationship between a predictor variable and a criterion variable (Fig. 2-2). Suppose a researcher is interested in examining whether familial stress (e.g., in the context of a child’s chronic illness) is associated with the child’s psychological adjustment and, more specifically, whether this effect becomes more or less robust in the presence of other contextual variables. For example, the strength or the direction of the relationship between stress and adjustment may depend on the level of uncertainty that characterizes the child’s condition; that is, a significant association between stress and adjustment may emerge only when there is considerable uncertainty regarding the child’s illness status. By testing “level of uncertainty” as a moderator of the relationship between stress and outcome, the researcher can specify certain conditions under which family stress is predictive of the child’s adjustment.

FIGURE 2-2 Moderated relationship among variables. A, Predictor; B, moderator; C, criterion/outcome.

(From Rose BM, Holmbeck GN, Coakley RM, et al: Mediator and moderator effects in developmental and behavioral pediatric research. J Dev Behav Pediatr 25:1-10, 2004. Copyright 2004 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Reprinted with permission.)

Developmental-behavioral pediatric researchers often posit mediational and moderational processes when conducting studies of risk and protective factors. In general, research on risk and protective factors is focused on understanding the adjustment of children who are exposed to varying levels of adversity. There is evidence that both contextual factors (e.g., socioeconomic status, family level functioning, peer relationships) and developmental variables (e.g., cognitive skills, autonomy development) can significantly influence outcomes for individuals living under adverse conditions and thus serve a moderational role.21–24 Risk and protective processes have been explored in the study of “resilience,” a term used with increasing frequency in developmental and pediatric research (see later section on resilience). Resilience refers to the process by which children successfully navigate stressful situations or adversity and attain developmentally relevant competencies.25 More generally, appropriate application of these terms (i.e., resilience, risk factors, protective factors) is necessary for promoting terminological consistency.

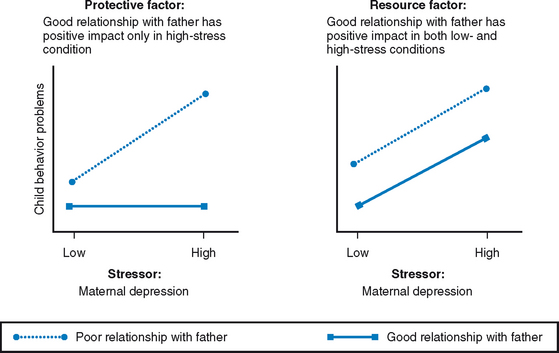

PROTECTIVE VERSUS RESOURCE FACTORS

Protective factors are contrasted with resource factors. Specifically, a factor that has a positive effect on the sample regardless of the presence or absence of a stressor is a resource factor24 (sometimes referred to as a promotive factor26). For example, if a positive father-child relationship reduces behavior problems only in children of depressed mothers but has no effect on children of nondepressed mothers, then the father-child relationship would be conceptualized as a protective factor (Fig. 2-3).18 However, if the positive father-child relationship reduces behavior problems in all children, regardless of the mother’s level of depression, then it would be conceptualized as a resource factor (see Fig. 2-3).18,24 A model may also identify a positive father-child relationship as both a protective and resource factor if it reduces behavior problems in children who have depressed mothers more than in children who have nondepressed mothers but if it also produces a significant reduction in behavior problems for all children, regardless of level of maternal depression. It is also important to note that a protective factor represents a moderational effect (see the statistically significant interaction effect in Fig. 2-3, left), whereas a resource factor represents an additive effect (i.e., two main effects; see Fig. 2-3, right).18

FIGURE 2-3 Protective factors (left) and resource factors (right).

(From Rose BM, Holmbeck GN, Coakley RM, et al: Mediator and moderator effects in developmental and behavioral pediatric research. J Dev Behav Pediatr 25:1-10, 2004. Copyright 2004 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Reprinted with permission.)

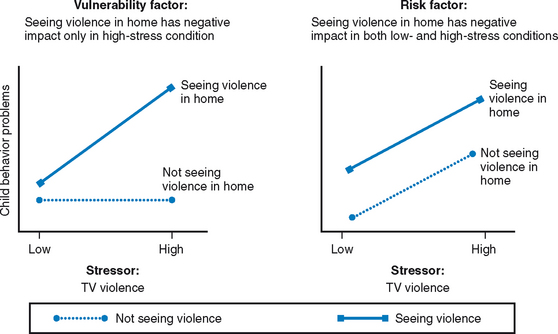

RISK VERSUS VULNERABILITY FACTORS

Risk and vulnerability factors operate in much the same way as resource and protective factors but in the opposite direction (Fig. 2-4).18 A vulnerability factor is a moderator that increases the chances for maladaptive outcomes in the presence of adversity.24 Like a protective factor, a vulnerability factor operates only in the context of adversity. In contrast, a variable that negatively influences outcome regardless of the presence or absence of adversity is a risk factor.24 For example, witnessing violence in the home environment is conceptualized as a vulnerability factor if it increases behavior problems only in children who are also exposed to a stressor, such as viewing extreme violence on television (see Fig. 2-4, left).18 A vulnerability factor is a moderator and is demonstrated statistically with a significant interaction effect. Witnessing violence in the home can be conceptualized as a risk factor if it results in an increase in child behavior problems for all children, regardless of the amount of television violence witnessed. As with resource factors, a risk factor represents an additive effect (i.e., two main effects; see Fig. 2-4, right).18 A model may also identify a factor as being both a risk and vulnerability factor if it increases the chance of a maladaptive outcome in samples with and without exposure to a stressor but also if it increases the chances for maladaptive functioning significantly more in the sample with the stressor.

FIGURE 2-4 Vulnerability factors (left) and risk factors (right).

(From Rose BM, Holmbeck GN, Coakley RM, et al: Mediator and moderator effects in developmental and behavioral pediatric research. J Dev Behav Pediatr 25:1-10, 2004. Copyright 2004 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Reprinted with permission.)

In sum, if a factor significantly promotes or impairs the chances of attaining adaptive outcomes in the presence of a stressor, then it operates through protective or vulnerability mechanisms, respectively. In these cases, the factor serves a moderational role. However, if a factor significantly promotes or impairs the chance of attaining adaptive outcomes without differentiating between the presence or absence of a stressor, then it is conceptualized as operating through resource or risk mechanisms, respectively. Many examples of these types of effects have appeared in the literature. For example, in their study of maltreatment and adolescent behavior problems, McGee and associates found that the association between severity of physical abuse and internalizing symptoms was moderated by gender.27 Specifically, the association was positive and significant for girls but not for boys. In other words, being male could be considered a protective factor against the development of internalizing symptoms when a person is exposed to high levels of physical abuse. Similarly, Gorman-Smith and Tolan found that associations between exposure to violence and anxiety/depression symptoms in young adolescents were moderated by level of family cohesion.28 The effect was significant (and positive) only at low levels of cohesion. At high levels of cohesion, the effect was nonsignificant, which suggests that family cohesion buffers (or protects against) the negative effects of exposure to violence on adolescent mental health.

Some investigators have sought to examine risk factors as mediational causal chains over time. For example, Tolan and colleagues examined a causal chain as a predictor of violent behaviors in adolescence, which included the following variables (in temporal order): community structure characteristics, neighborliness, parenting practices, gang membership, and peer violence.29 Woodward and Fergusson examined predictors of increased rates of teen pregnancy and found a causal chain that began with early conduct problems; such problems were associated with subsequent risk-taking behaviors in adolescence, which placed girls at risk for teen pregnancy.30

Clear Implications for Interventions

Perhaps, of most importance, a theory should have clear implications for interventions. Although many variables have potential intervention implications, some are clearly more relevant to practice than are others. For example, suppose a researcher is examining predictors of medical adherence during adolescence in children with type 1 diabetes. The researcher could examine parent and child adherence-relevant problem-solving ability as a predictor of subsequent levels of adherence, or the researcher could examine adolescent personality variables (e.g., neuroticism) as predictors of adherence. Clearly, it would be easier to imagine developing an intervention that targets problem-solving ability than one that targets a personality variable. Moreover, the researcher would speculate that problem-solving ability is also more likely to be responsive to an intervention than is a personality variable. Interestingly, some variables may not appear to be intervention-relevant at first glance but may become so on further examination. For example, demographic variables (e.g., gender, social class) would obviously not be targets of an intervention, but they may be important markers for risk. For example, the researcher may find that individuals from the lower end of the socioeconomic distribution are at increased risk for medical adherence difficulties; thus, this subpopulation could be targeted as an at-risk group and receive a more intense intervention.

Not only do predictor-outcome studies have implications for intervention work but also intervention studies themselves can be very instructive. Specifically, a research design that includes random assignment to intervention condition provides a particularly powerful design for drawing conclusions about causal mediational relationships.31,32 These types of models have three important strengths. First, significant mediational models of intervention effects provide information about mechanisms through which treatments have their effects.33–35 Simply put, with such models, researchers are able to ask how and why an intervention works.33 Second, as noted by Collins and associates, if a manipulated variable (i.e., the randomly assigned intervention) is associated with change in the mediator, which is in turn associated with change in the outcome, there is significant support for the hypothesis that the mediator is a causal mechanism.36 Researchers are more justified in invoking causal language when examining mediational models in which the predictor is manipulated (i.e., random assignment to intervention vs. no intervention) than in mediational models in which no variables are directly manipulated. With random assignment, many alternative interpretations for a researcher’s findings can be ruled out, and thus it is more certain that changes in the outcomes (e.g., symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]) result from the intervention instead of from some other factor.

Third, when a researcher isolates a significant mediational process, the researcher has learned that the mediator may play a role in the maintenance of the outcome (e.g., problem behavior). In this way, knowledge about mediational processes in the context of randomized clinical trials informs investigators about etiological theories of disorders.33,37 As an example of this strategy, Forgatch and DeGarmo examined the effectiveness of a parenting-training program for a large sample of divorcing mothers with sons.38 They also examined several parenting practices as mediators of the intervention→child outcome association. In comparison with mothers in the control sample, mothers in the intervention sample showed improvements in parenting practices. Improvements in parenting practices were linked with improvements in child adjustment. Thus, this study provides important evidence that certain types of maladaptive parenting behavior maintain certain maladaptive child outcomes.

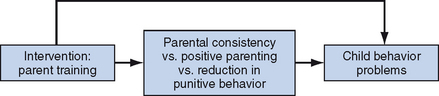

Such intervention/mediation models not only allow researchers to test potential mediators within an experimental design but also allow researchers to examine the differential utility of several mediational variables. In other words, a researcher can determine which mediator best accounts for the effectiveness of a given treatment. For example, if researchers examined the effectiveness of parenting training for decreasing child behavior problems (as in the preceding example), they might target three areas of parenting with this intervention: parental consistency, positive parenting, and harsh/punitive parenting. By testing mediational models within the context of an intervention study, they could determine which of these three parenting targets accounts for the significant intervention effect. It may be, for example, that the intervention’s effect on parental consistency is the mechanism through which the treatment has an effect on child outcome. This component of the treatment could then be emphasized and enhanced in future versions of the intervention (Fig. 2-5).18

This overview of features shared by the most influential theories provides the basis for a focused review of theories relevant to the field of developmental-behavioral pediatrics.

THEORETICAL MODELS IN DEVELOPMENTAL-BEHAVIORAL PEDIATRICS

It would, of course, be impossible to provide an overview of all relevant theories in the field of developmental-behavioral pediatrics. Thus, we have chosen theories from five areas that are of primary concern to developmental-behavioral pediatricians: (1) theories that take into account biological, genetic, and neurological bases for behavior; (2) transactional models of development; (3) theoretical principles from the field of developmental psychopathology (a relatively new discipline through which investigators seek to understand how problem behaviors develop and are maintained across the lifespan); (4) theories of adjustment to chronic illness; and (5) models relevant to medical adherence. Some important models are not covered because they are highlighted in other chapters in this volume (e.g., for a review of family systems theory and models of cultural influence, see Chapter 5).

A Brief Historical Perspective on Child Development

Modern theories of developmental-behavioral pediatrics have their roots in early theories of child development. The purpose of this section is to trace the history of some of the important constructs that are now taken for granted in more recent theorizing. In an earlier review for a volume on developmental-behavioral pediatrics, Kessen provided a comprehensive overview of past theories and research on human behavioral development (beginning with work conducted as early as 1850).6 Moreover, in the four-volume fifth edition of the Handbook of Child Psychology, an entire volume (more than 1200 pages) is devoted to “theoretical models of human development.” Thus, a complete overview of this area is well beyond the scope of this chapter.

The study of human development is a field devoted to identifying and explaining changes in behavior, abilities, and attributes that individuals experience throughout their lives. Because infants and young children change so dramatically over a relatively short time, they received intense empirical scrutiny in past research. However, in more recent years, research has been focused on developmental issues of relevance over the entire lifespan.39 Although the field of developmental psychology has undergone many changes since its advent in the late 1800s, several themes have been revisited throughout the past century.40 These include (1) the nature/nurture issue (i.e., what is the relative importance of biological and environmental factors in human development?), (2) the active/passive issue (i.e., are children active contributors to their own development, or are they passive objects, acted on by the environment?), and (3) the continuous/discontinuous issue (i.e., are developmental changes better seen as discontinuous or continuous?).6,41 These themes emerge throughout the following discussion of some of the most influential early theorists.

Charles Darwin’s A Biological Sketch of an Infant was the most influential of the “baby biographies” and is often cited as the impetus for the child study movement.42 His theory of evolution could be considered the underlying theoretical force behind the entire discipline of developmental psychology, and its influence continues to inspire present-day thought in the field. For example, Boyce and Ellis’s theory of biological stress reactivity (as discussed in a later section) is one example of a modern idea that is largely inspired by evolutionary theory.43 However, before Boyce and Ellis’s notion of biological stress reactivity, Darwinian theory influenced many other notable contributors, including one who would come to be known as the founder of American developmental psychology: G. Stanley Hall (1844–1924). Hall believed that human development follows a course similar to that of the evolution of the species.44,45 He acknowledged the scientific shortcomings of the baby biographies (which were based on potentially biased observations of small numbers of children) and attempted to collect more objective data on larger samples. In 1891, he began a program of questionnaire studies at Clark University in what is often considered the first large-scale scientific investigation of developing youth. Although research has since cast doubt on his “storm and stress model” as described in Adolescence, Hall was instrumental in bringing recognition to this period as a distinct and defining time of growth and transition.44

Hall is also recognized for his role as a mentor and administrator. In 1909, he invited Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) to Clark University, thereby generating international recognition for psychoanalytic theory. Originally trained as a neurologist, Freud observed that many of the physical symptoms seen in his patients appeared to be emotional in origin.46 Through a methodology much different from that employed by Hall, Freud used free association, dream interpretation, and hypnosis to analyze the histories of his emotionally disturbed adult patients. On the basis of his analyses, Freud proposed that development occurs through the resolution of conflict between what a person wants to do versus what the person should do. He suggested that everyone has basic biological impulses that must be indulged but that society dictates the restraint of these impulses. This notion formed the basis of Freud’s theory of psychosexual development. Although many of Freud’s ideas have not been supported by empirical evidence, no one would refute that his contributions changed clinicians’ thinking within the field. For instance, he was the first to popularize the notion that childhood experiences affect adult lives, as well as the first to introduce the idea of a subconscious motivation. In addition, Freud advanced the field by addressing the emotional side of human experience, which previous theorists had neglected.46

Freud was also the first prominent theorist to endorse an interactionist perspective, which acknowledged both biological and environmental factors that influence human development (although he emphasized the impact of environmental factors, such as parenting). Insofar as most theorists today consider both genetic and environmental factors that contribute to a person’s development (e.g., diathesis-stress model of psychopathology), Freud’s influence continues. In contrast to Freud’s interactionist viewpoint, the maturational theory of Arnold Gesell (1880–1961) represents a prominent biological theory of child development.47 In Gesell’s view, development is a naturally unfolding progression that occurs according to some internal biological timetable, and learning and teaching cannot override this timetable.48 He maintained that children are “self-regulating” and develop only as they are ready to do so. Gesell is noteworthy for the detailed studies of children’s physical and behavioral changes that were carried out under his supervision throughout his tenure at the Yale Clinic of Child Development. The results of Gesell’s observational studies revealed a high degree of uniformity in children’s development. Although developmental milestones may not have occurred at the same age for all children, the pattern of development was largely uniform (e.g., children walk before they run and run before they skip). Gesell used his data to establish statistical norms to describe the usual order in which children display various early behaviors, as well as the age range within which each behavior normally appears. Interestingly, physicians still use updated versions of these norms as general guidelines for normative development. Gesell also made important contributions to methodology in the field of psychology. He was the first to capture children’s observations on film, thereby preserving their behavior for later frame-by-frame study, and he also developed the first one-way viewing screens.

Although Gesell was influential in terms of his contributions to methodology and his establishment of developmental norms, his purely biological theory was deemed an oversimplication of the complex process of human development insofar as it neglected to account for the importance of children’s experiences. However, his emphasis on similarities across children’s development and his focus on patterns of behavior set the stage for Jean Piaget (1896–1980), who is often credited for having the greatest influence on present-day developmental psychology.49 Unlike the theorists previously discussed, many of Piaget’s general theoretical hypotheses are still widely accepted by developmental psychologists. One reason his theories are appealing is that they complement other theories well. For instance, more recent thinkers in developmental psychology combine aspects of Piagetian theory with information processing and contextualist perspectives to more thoroughly understand the process of cognitive development.

Piaget became interested in child cognitive development through the administration of intelligence tests. He was interested less in the answers that children provided to test questions than in the reasoning behind the answers they gave. He soon realized that the way children think is qualitatively different from how adults think. Piaget became immersed in the study of the nature of knowledge in young children, as well as how it changes as they grow older.50–52 He termed this area of study genetic epistemology. Unlike Gesell’s method, in which the researcher stood apart from his objects of study, Piaget developed a research technique known as the clinical method. This involved presenting children with various tasks and verbal problems that would tap into children’s reasoning. Although he would begin with a set of standardized questions, he would then probe children’s responses with follow-up questions to reveal the reasoning behind their responses. According to Piaget’s cognitive-developmental theory, children universally progress through a series of stages: the sensorimotor stage (birth to age 2 years), the preoperational stage (ages 2 to 7 years), the concrete operational stage (ages 7 to 11 years), and the formal operational stage (ages 11 years and beyond). Piaget’s theory is extremely complex, and a discussion of the processes by which children progress from stage to stage is beyond the scope of this chapter.50

Although Piaget’s ideas about children are still widely accepted today, his theory has not gone without criticism. One major criticism of his theory concerns its lack of emphasis on cross-cultural factors that may play a role in development. Although Piaget acknowledged that culture may influence the rate of cognitive growth, he did not address ways in which culture can affect how children grow and develop. He is also criticized for overlooking the role of social interactions in cognitive development. This latter idea is the hallmark of Lev Vygotsky’s (1896–1934) sociocultural perspective.53,54 According to Vygotsky, cognitive development occurs when children take part in dialogs with skilled tutors (e.g., parents and teachers).55 It is through the process of social interaction that children incorporate and internalize feedback from these skilled tutors. As social speech is translated into private speech and then inner speech, the culture’s method of thinking is incorporated into the child’s thought processes. Vygotsky is also noteworthy for his consideration of the way cognitive development varies across cultures. Unlike Piaget, who maintained that cognitive development is largely universal across cultures, Vygotsky argued that variability in cognitive development that reflects the child’s cultural experiences should be expected. As such, Vygotsky played a role in the movement toward cross-cultural and contextually oriented studies in developmental psychology. His influence can also be seen in the more recent literature on child and adolescent development, in which various contexts (e.g., family, peers, school, work) are considered with regard to their unique influences on development.

Current Theories in Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics

MODELS THAT FOCUS ON BIOLOGICAL, GENETIC, AND NEUROLOGICAL BASES FOR BEHAVIOR

Several models of child functioning that focus on biological, genetic, and neurological bases for behavior have been proposed. It is believed that biologically based vulnerabilities can account, at least in part, for the emergence of certain psychosocial difficulties (e.g., depression, anxiety). In this section, models in the areas of biological stress reactivity and behavioral genetics (including a discussion of shared and nonshared environmental effects) are emphasized. Neurodevelopmental factors relevant to developmental-behavioral pediatricians are discussed thoroughly in Chapter 4.

BIOLOGICAL STRESS REACTIVITY

Stress reactivity is an individual differences variable that refers to an individual’s physical neuroendocrine response to stressful events and adversity.43 Researchers measure such reactivity with a host of physiological assessment techniques, including measures of heart rate, blood pressure, salivary cortisol, and respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Early research and theorizing on stress reactivity suggested that heightened or prolonged reactivity in response to stressors is maladaptive and places the individual at risk for adjustment difficulties (including affective disorder, anxiety disorders, and externalizing symptoms) and medical illness (e.g., heart disease). On the other hand, such reactivity may be adaptive in the short term by preparing the individual to confront external threats. Moreover, when significant stressors occur early in an individual’s life, such individuals appear to be at risk for heightened levels of stress reactivity.

In 2005, Boyce and Ellis proposed a complex and intriguing theory of biological stress reactivity.43 On the basis of a comprehensive review of research findings (including anomalous findings) in this literature, they concluded that the relationship between reactivity and outcome is not so straightforward. Rather, they proposed, according to an evolutionary-developmental theory, that high reactivity can result from exposure to highly stressful environments or from exposure to highly supportive/protective environments. As in previous theorizing, they maintained that early exposure to highly stressful environments can cause heightened reactivity (such individuals are more prepared for future occurrences of highly stressful events). But they also proposed that environments with very low stress can also produce children with heightened reactivity because such reactivity levels enable such children to experience more completely the beneficial characteristics of a protective environment. They argued further that this curvilinear relationship between early stress and reactivity is a process that has evolved through natural selection and one that affords advantages to both of these highly reactive groups. They concluded, “Highly reactive children sustain disproportionate rates of morbidity when raised in adverse environments but unusually low (emphasis added) rates when raised in low-stress, highly supportive settings.” Interestingly, in a empirical investigation that was a companion to their theoretical paper, Ellis and associates found support for many of their propositions.56 Empirical support for this viewpoint has also emerged in studies of primates.57

Another intriguing theory of stress reactivity was proposed by Grossman and colleagues, who discussed longitudinal changes in stress reactivity in depressed individuals.58 They argued that the interplay between stressful environmental events and genetic expression can produce “potentiated stress reactivity” over time.58 They suggested that early stressful events may alter genetic expression, whereby depressive episodes are triggered by increasingly less intense environmental and psychological stressors over time. The term kindling is used to explain this process in which life experiences produce subtle changes in brain functioning, genetic expression, and stress reactivity. They also invoke Waddington’s compelling concept of “canalization.”59 The argument here is that development progresses in a “canal” of normative development that increases in “depth” with age. Psychopathology (e.g., depression) is likely to result if the individual is pushed up the sides of the canal beyond a genetically determined threshold (i.e., the threshold is higher in the canal for some individuals than for other individuals). In typically developing individuals, and because of the increasing depth of the canal, early stressors are more likely to move the individual beyond the pathology threshold than are stressors that occur later in life. With regard to depression, a severe stressor early in childhood can produce a depressive episode. After recovery from this episode, the individual can experience a second episode (moving above the threshold in the canal) as a result of another, less intense stressor. Genetics may influence the severity of the stressor that is necessary for the initial episode and the pace at which the kindling process takes hold.58 The following case example illustrates how such a process may unfold:

BEHAVIORAL GENETICS

Two important areas of behavioral genetics are discussed in this section. First, a number of investigators have examined ways in which there are gene × environment interactions, whereby the effect of certain environmental conditions may be exacerbated (or buffered) depending on the level of genetic vulnerability. Second, the field of behavioral genetics has attempted to shed light on how behavioral variation observed among children and adolescents can be ascribed to either genetic or environmental processes or to both. Researchers in this area have contributed to the field by investigating how both “nature” and “nurture” are the precursors of normal as well as abnormal behavior.60,61 We begin with a discussion of gene × environment interactions and later discuss how investigators have attempted to partition variance into genetic and environmental effects.

Whether an individual is more a product of his or her genetic makeup versus his or her environment has been long debated. However, research in the fields of medicine and psychology has indicated that these influences are rarely distinct from one another and that their effects are probabilistic rather than determinative.62 For example, modifications in lifestyle can decrease the risk of heart disease in an individual who is genetically prone to this illness.

Investigators who study joint effects of genes and environment on psychopathology distinguish between gene-environment interactions and gene-environment correlations.63 Gene-environment interactions represent the diathesis-stress model of psychopathology. According to this model, certain environmental stressors contribute to the emergence of psychopathology in individuals who have a genetic vulnerability (i.e., diathesis). In this way, associations between stress and outcome are moderated by genetic vulnerability. In a set of intriguing studies, Caspi and colleagues identified polymorphisms in specific genes that moderate the effects of negative life experiences on the emergence of both antisocial behavior and depression.64,65

Unlike gene-environment interactions, gene-environment correlations refer to significant associations between genetic vulnerabilities and environmental risk, whereby individuals with higher levels of genetic vulnerability are more likely to be exposed to higher levels of environmental risk.63 Hypothesized mechanisms for gene-environment correlations include (1) a passive process, whereby environmental risk is beyond the individual’s control; (2) an evocative process, whereby an individual with a certain genetic vulnerability elicits certain toxic characteristics from the environment; and (3) an active process, whereby an individual with a certain genetic vulnerability actively alters or promotes a specific type of environment. To illustrate these hypothesized mechanisms, consider the example of a child with a genetic vulnerability to ADHD:

Studies of depression, anxiety, and antisocial behavior have supported the role of both gene-environment interactions and gene-environment correlations.62,64–67

The degree to which there is interplay between genetic and environmental factors may also be dependent on developmental timing and contextual influences. For example, studies of the roles of genes and environment on depressive symptoms have suggested that environmental factors are associated with depressive symptoms in childhood. However, during adolescence and adulthood, genes appear to play a more salient role.68 In addition, in terms of gene-environment correlations, passive processes, such as family influences, may be more prominent during early childhood. Evocative and active gene-environment correlations may play a greater role later in development.69 Finally, the strength of genetic influence may be dependent on environmental context. For example, genetic factors appear to play a weaker role in the intellectual development of children raised in impoverished environments than in those raised in more affluent environments.70

Grossman and colleagues noted that the manifestation of many pathological conditions that may, at first glance, appear to be produced entirely by genetic factors or environmental factors may, in fact, be produced by a combination of genetic and environmental factors.58 Fetal alcohol syndrome is an example of a disorder that is caused environmentally (by fetal exposure to alcohol). Clinical outcomes associated with fetal alcohol syndrome result from disruption of several neurodevelopmental processes. On the other hand, the developmental processes that are affected depend on several factors. For example, large single-episode quantities of alcohol are more detrimental to fetal brain development than are several exposures to low levels of alcohol. Moreover, effects are greater in the later stages of pregnancy. Thus, although fetal alcohol syndrome is clearly caused by environmental factors, it is also true that environmental factors are interacting with “genetically determined developmental time courses” to produce varying detrimental effects on brain development.58 Unlike fetal alcohol syndrome, fragile X syndrome is an example of how a genetically caused disorder can be influenced by environmental factors, inasmuch as individuals with fragile X syndrome vary widely in their presentation. Environmental factors, such as the quality of the home environment, can interact with genetic effects to lead to significant variability in outcomes for individuals afflicted with fragile X syndrome.58

With regard to the partitioning of individual variation (e.g., variation in childhood problem behaviors) into environmental and genetic effects, classic behavioral genetics research methods include family, twin, and adoption study designs. Adoption and twin studies, in which the family members of varying genetic relatedness are compared, are needed to disaggregate genetic and environmental sources of variance. For example, if heredity affects a behavioral trait, then it follows that monozygotic twins will be more similar to each other with regard to that trait than will dizygotic twins. A stepfamily design is also used in which monozygotic twins and dizygotic twins are compared, along with full siblings, half-siblings, and unrelated siblings living in the same household.60,61,71

Most of the work in behavior genetics has employed an additive statistical model. One basic assumption of the additive model is that genetic and environmental influences are independent factors that sum to account for the total amount of individual variation. This model partitions the variance of the characteristic being studied among three components: genetic factors, shared environmental influences, and nonshared environmental influences. A heritability estimate, which ascribes an effect size to genetic influence, is calculated. The variance left over is then ascribed to environmental influences.36,60,61,71

Environmental influences are then further subdivided into shared and nonshared types. The term shared environment refers to environmental factors that produce similarities in developmental outcomes among siblings in the same family. If siblings are more similar than would be expected from their shared genetics alone, then this implies an effect of the environment that is shared by both siblings, such as being exposed to marital conflict or poverty or being parented in a similar manner. Shared environmental influence is estimated indirectly from correlations among twins by subtracting the heritability estimate from the monozygotic twin correlation. Nonshared environment, which refers to environmental factors that produce behavioral differences among siblings in the same family, can then be estimated. Nonshared environmental influence is calculated by subtracting the monozygotic twin correlation from 1.0.60,61,71 In the stepfamily design described previously, shared environmental influence is implicated when correlations among siblings are large across all types of sibling pairs, including those that are not related. On the other hand, nonshared environmental influence is implicated when sibling correlations are low across all pairs of siblings of varying genetic relatedness, including monozygotic twins.72

Results of multiple studies with genetically sensitive designs suggest that many aspects of child and adolescent psychopathology show evidence of genetic influence.60,61,71 Autism and Tourette syndrome in particular have been demonstrated to be mostly genetically determined.61,71 Genetic factors have also been found to strongly influence externalizing behaviors, including aggression.73 Although the results are less clear, genetic influence has been associated with the development of internalizing problems as well.74 However, genetic influence does not account for all of the variance in psychopathological disorders.60,61,71 For example, the environmental conditions under which children and adolescents are socialized play an important role. Interestingly, however, it is the environmental factors that are not shared—those that create differences among siblings and not shared environmental factors—that seem to contribute to a large portion of the variation. Environmental factors that have been postulated to be nonshared include differential treatment by parents, peer influences, and school environment.60,61,71

Nonshared environmental factors have been implicated in hyperactivity, anorexia nervosa, aggression, and internalizing symptoms.71 In addition, the combination of nonshared and genetic influences may influence the adolescent’s choice of peer group.75 Juvenile delinquency appears to be one exception to the rule in that shared environmental factors have been shown to be more influential than nonshared environmental or genetic factors.71

Behavior genetics research has gone beyond the partitioning of variance into genetic and environmental components. For example, researchers have examined how differential parenting practices may produce differing developmental outcomes among siblings. One study revealed that more than 50% of the variance in antisocial behavior and 37% of the variance in depressive symptoms were associated with conflictive and negative parenting behavior that was directed specifically at the child.76 However, research has also suggested that longitudinal associations between both parenting behavior and child adjustment may be explained partly by genetic factors,77 which suggests that genetically influenced characteristics of the child may elicit specific types of parenting behavior. In this way, nonshared experiences of siblings may in fact reflect genetic differences, such as differences in temperament.78 One adoption study demonstrated that those who were at genetic risk for the development of antisocial behavior, by virtue of having a biological parent with a disorder, were more likely than children without this risk to be exposed to coercive parenting by their adoptive parents.79

Another important question examined in behavioral genetics research is whether genetic influences are more prominent at the extreme range of a psychopathological condition. By examining the full range of symptoms rather than specific diagnoses, behavior genetics research may highlight the continuity or discontinuity between normal and abnormal development.61 One study showed that although variation in subclinical depressive symptoms is influenced mostly by genetics, adolescent depressive disorder appears to be influenced mostly by shared environmental factors.74 Behavior genetic research has also demonstrated that genetic influences may partly explain comorbidity among disorders.60 One study demonstrated that half of the correlation between externalizing and internalizing behaviors can be explained by common genetic liability.72

Researchers have pointed to the many limitations of behavior genetics research that need to be considered when these findings are evaluated.34,36,80,81 In particular, the additive statistical model, the assumption that lies at the heart of behavior genetics methodology, has been criticized as neglecting to consider the potentially important contribution of gene-environment interactions (see earlier discussion). As noted previously, genetic and environmental influences may also be correlated.34,36,80–82 Stable heritability estimates are also difficult to calculate. These estimates are highly influenced by the range of genetic and environmental variations within the sample and also tend to be influenced by reporter. For example, parent reports of child characteristics tend to show lower heritability estimates than when the same characteristics are reported on by children or teachers or when observational measures are used.81 If heritability estimates are unstable, then estimates of environmental influences, derived from heritability estimates, are also unstable.81 Critics have suggested that environmental influences cannot be estimated without being measured directly. However, the methods used in studies of environmental factors, such as differential parenting, may also be difficult to interpret. For example, genetic similarity may be confounded with family structure in that full siblings are likely to have more congruent parenting experiences than are half-siblings or step-siblings.80,81 Also, shared events, such as those found in similar family environments, may contribute to nonshared variance in that different siblings may be affected differently by the same experiences.60

TRANSACTIONAL MODELS OF DEVELOPMENT

Transactional models have been crucial in highlighting how children can have an effect on their environment (e.g., their parents). For example, parents may not be aware that their children can have significant effects on their parenting and that children are not merely passive recipients of their parenting behaviors and values. As one example, it is known that a child’s temperament (i.e., adaptability, reactivity, emotionality, activity level, sociability) has a significant effect over time on the nature and quality of a parent’s behaviors toward the child.83

Studies of temperament and attachment provided early support for a transactional model of development.84,85 Theories that postulated that negative temperament was simply a result of poor parenting behaviors were replaced by the idea that specific child characteristics elicited maladaptive parenting, which later resulted in child behavioral difficulties.86 Similarly, increasing emphasis has been given to the child’s role in the development of attachment style, as illustrated in the following case example:

Consistent with Bronfenbrenner’s biopsychosocial model,87 various levels of context can interact with one another and either directly or indirectly affect child development. For example, in the context of poor maternal social support, irritable infants may elicit unresponsive mothering, leading to insecure attachment.88 However, when provided with adequate social support, mothers may be able to respond to their children in a more positive manner, thereby promoting secure attachment.

In addition, the relative importance of various contexts on development is dependent on developmental timing. Whereas the family context is primary during infancy and early childhood, interactions with teachers and peers take on increasing importance in late childhood and adolescence.89,90 Research on conduct problems has supported this notion. In early childhood, children who exhibit difficult temperament and noncompliant behavior often elicit punitive and inadequate parenting practices, which may actually serve to reinforce noncompliant behaviors.91,92 Over time, parents and child may engage in interactions in which parenting becomes increasingly harsh and child behavior more noncompliant and aggressive. This transactional pattern appears to be especially salient in the context of poverty, as inherent parental stress and lack of access to resources may compromise parenting ability.89 In the school environment, the child’s aggressive behavior may lead to negative teacher-child interactions, contributing to poor academic achievement and negative peer interactions, resulting in peer rejection and poor self-esteem.89 Indeed, phenomena such as peer rejection have been found to both predict and be predicted by conduct problems.89 Additional research has supported the role of transactional processes in disrupting parent-child interactions and peer functioning in other types of psychopathology, such as depression and ADHD.66,93

Transactional processes contribute to the understanding of continuity, or maintenance, of psychopathology and personality characteristics, over time, through these cyclical interaction processes between the individual and the environment.94 Hence, lack of healthy adaptation over time is probably a reflection of continued dysfunctional interaction between an individual and his or her environment.95,96 Some studies of depression have differentiated between dependent and independent negative life events, occurrences that are within versus beyond an individual’s control, respectively. This research has demonstrated that whereas the onset of depression may result from the occurrence of independent negative life events, depressive symptoms may be maintained by dependent negative life events.66

The exacerbation and emergence of new psychosocial difficulties also can be understood through transactional processes. For example, aggressive individuals may be prone to peer rejection as a result of their aggressive behaviors. This “self-generated” peer rejection may create negative life events linked to depression.66 In addition, these individuals may hold cognitive biases that lead them to expect and misperceive others’ actions as rejecting, thereby further contributing to the negative cycle of aggression and depression.66

Transactional models of development are also suggestive of targets for interventions. Indeed, efforts to change perceptions, expectations, and child-environment interactions, through parent training, have proved successful in terms of promoting healthy attachment and reducing conduct problems in infants and children, respectively.97–99

DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

Developmental psychopathology could be considered a metatheory, or a macroparadigm that integrates knowledge from many fields, including lifespan developmental psychology, clinical child psychology, family systems, neuroscience, and behavioral genetics, to name just a few.100,101 As such, this section is the longest and most detailed of the “current theory” sections. Developmental-behavioral pediatricians can benefit greatly from knowledge of this field because of its emphasis on tracing the evolution of problems in development. In this way, informed pediatricians can play a key role in identifying children who are manifesting the beginnings of maladaptive developmental trajectories and who are probabilistically at risk for eventually developing more severe levels of pathological behavior. In view of the young ages of their patients, they also have the first opportunity to recommend or provide interventions designed to reduce risk.

Assumptions and Tenets of the Developmental Psychopathology Perspective

The goal of developmental psychopathology is to understand the unfolding of psychopathology over the lifespan and how the processes that lead to psychopathology interact with normative developmental milestones and contextual factors.101,102 Some of the assumptions and tenets of this field are as follows:101,102

Developmental Trajectories during Childhood and Adolescence: Multifinality and Equifinality

As implied previously, proponents of the developmental psychopathology perspective attempt to understand how pathology unfolds over time, rather than examining symptoms at a single time point. As a consequence, developmental psychopathologists have found the notion of “developmental trajectories” very useful.101 For example, researchers could examine alcohol use and isolate different developmental trajectories of such use over time (e.g., some youth may show rapid increases in alcohol use over time, some may show gradual increases, and others may show increases followed by decreases109).

It is also assumed that some developmental trajectories are indicative of a developmental failure that probabilistically increases the chances that a psychopathological disorder will develop at a later point in time.101 Thus, there is an interest in isolating early-onset trajectories that portend later problems. As an example, Dodge and Pettit pointed out that children who have early difficult temperaments (i.e., an early trajectory) who are also rejected by their peers for 2 or more years by grade 2 have a 60% chance of developing a serious conduct problem during adolescence.89 Again, this confluence of trajectory (i.e., difficult temperament) and risk factor (i.e., chronic peer rejection) does not automatically produce a conduct-disordered adolescent; rather, it merely increases the odds that the child will develop such a disorder.

In view of the vast individual differences in trajectories in any given domain of functioning, developmental psychopathologists have also been interested in the concepts of multifinality and equifinality.110 Multifinality occurs when there are multiple outcomes in those who have been exposed to the same antecedent risk factor (e.g., maternal depression). After equivalent exposure to a parent who is depressed, not all children so exposed will develop along identical pathways. In a study of multifinality, Marsh and colleagues examined outcomes of adolescents with insecure preoccupied attachment orientations (i.e., they all had the same starting point).111 Those adolescents with mothers who displayed low levels of autonomy in observed interactions were more likely to display internalizing symptoms. Conversely, those with mothers who displayed very high levels of autonomy were more likely to exhibit risky behaviors. Thus, multiple outcomes (i.e., multifinality) occur in those who all have the same initial risk factor (i.e., insecure preoccupied attachment orientation).

Equifinality occurs when individuals with the same level of psychopathology achieved such pathological outcomes through different pathways. Evidence for equifinality has emerged in research. For example, Harrington and associates found that suicidal behavior can be reached through different paths, one involving depression and another involving conduct disorder.112 Similarly, in girls, it appears that several of the same outcomes (e.g., anxiety disorders, substance use, school dropout, pregnancy) emerge in those with depression or conduct disorder.113 Finally, Gjerde and Block suggested that depressed adult women and men progress along very different developmental pathways before developing depression.114 It is worth noting, from an intervention perspective, that the presence of equifinality suggests that different versions of a given treatment for a given problem may be needed, depending on the pathway by which an individual progressed toward a psychopathological outcome.

Interestingly, the existence of such diverse types of trajectories has been supported by past research. For example, Lacourse and colleagues were able to isolate different trajectories of delinquent group membership in boys and their association with subsequent violent behaviors115 (see Zucker et al116 for a similar example involving a typology of alcoholics or Broidy et al117 for an example involving outcomes of typologies of childhood aggression). Such approaches have been termed person-oriented approaches (as opposed to variable-oriented), insofar as people are clustered into groups on the basis of the similarity of their characteristics or patterns of trajectories over time.118 Trajectory groups are differentiated on the basis of their patterning or profile of scores on antecedent or outcome variables of interest (e.g., maladaptive parenting, school failure). Moreover, such trajectories can assume quadratic forms (i.e., U-shaped functions).119

The Onset versus Maintenance of Psychopathology

It appears that factors that lead to the onset or initiation of a developmental trajectory are often different from those that maintain an individual on a developmental trajectory.108 This distinction has considerable clinical relevance. For example, a professional may be able to prevent the onset of sleep problems in young children by instructing parents on how to institute various behavioral plans early in development. Once a maladaptive sleep pattern emerges, other types of interventions may be needed.

With regard to maintenance of problem behaviors, an individual who has begun on a particular pathway may continue on the pathway or may be steered from the pathway.105 Factors that steer an individual from a maladaptive trajectory may be chance events, developmental successes, or protective processes that serve an adaptive function.102 In an analogous manner, other factors may steer individuals from adaptive trajectories onto maladaptive trajectories. It is an assumption of developmental psychopathology that maintenance on a pathway is more likely than steering away, particularly when an individual has moved through several developmental transitions on the same pathway.108

What do we know about factors that lead to the onset of maladaptive paths versus those that serve to maintain individuals on such pathways? Steinberg and Avenevoli argued that researchers have tended to confuse factors that lead to the onset of psychopathology versus those that lead to its maintenance and that this confusion has hampered progress in the field of developmental psychopathology.108 With regard to “onset,” Steinberg and Avenevoli argued (from a “diathesis-stress” perspective) that biological predispositions (e.g., temperament, level of autonomic arousal) can exacerbate or decrease the degree to which individuals are vulnerable to the effect of subsequent environmental stressors.108 Thus, two individuals exposed to the same stressor may begin on different pathways (e.g., anxiety vs. depression vs. aggression vs. no pathology), depending on the specific nature of each individual’s biological predispositions. Put another way, stressors appear to have nonspecific effects on the onset of pathology as a result of the moderating effect of particular biological vulnerabilities.108 These authors argued that future research on the elicitation of psychopathology needs to begin to isolate particular combinations of biological vulnerabilities and environmental threats that precede engagement with maladaptive developmental pathways. Indeed, such evidence is beginning to emerge; Brennan and associates found that early-onset and persistent aggression are predicted by interactions of biological and social risks (see later discussion of early- vs. late-onset psychopathology).120 Similarly, as noted earlier, Caspi and colleagues found support for a gene × environmental stress interaction effect in predicting depressive symptoms.65

With regard to “maintenance,” Steinberg and Avenevoli argued that environmental stressors have specific effects on the course of psychopathology.108 Thus, it is possible that two individuals may begin on the same pathway (as a result of having the same biological predispositions and same level of exposure to early stressors) but may have very different long-term outcomes if their environments differ. For example, two young children who have started on an early aggression pathway may diverge from each other over time because one of them is exposed to incompetent parenting, lack of structure, and deviant peers and the other is not (also see Dodge and Pettit89). Those who begin on an “early aggression” trajectory are probabilistically more likely to associate with deviant peers and “choose” maladaptive environments, but this is clearly not always the case for every affected child. Steinberg and Avenevoli also provided evidence that those who continue on certain paths and select certain environments are also more likely to strengthen the synaptic weights or connections of the original biological predisposition (e.g., the nature of the child’s arousal regulation capacities), which makes it even less likely that the individual will desist from this behavior or be steered from the maladaptive developmental trajectory.108 Put another way, psychopathology is likely to be maintained in individuals in whom the symptoms or the antecedents of the symptoms are repeated.108 In the preceding example, “lack of structure” in the family environment may not be a factor in the onset of conduct problems, but it may help maintain these problems because it permits more exposure to deviant peers and permits the pathological process to become more ingrained and entrenched.108

Researchers in several areas have begun to distinguish between onset and maintenance in their research designs (e.g., in the area of substance use, see Brook et al121; in the area of antisocial behavior, see Patterson et al122). For example, Dodge and Pettit89 provided a model of chronic conduct problems that is consistent with the notions advanced by Steinberg and Avenevoli.108 Dodge and Pettit argued that the bulk of research on conduct problems in childhood and adolescence suggests that children with certain neural or psychophysiological predispositions are more likely than others to begin a trajectory leading to conduct problems in adolescence. Such children are more likely to be parented harshly or neglected, because of their early difficult temperament. Outside the family, such children are more likely to be aggressive and to engage in conflict with peers during early childhood. According to Dodge and Pettit, such children enter elementary school in an at-risk state (although this transition is also an opportunity for steering away from this trajectory).89 Most often, such children experience peer rejection and have difficult relations with teachers. This combination of harsh parenting and peer rejection serves to stabilize the negative trajectory, which makes it less likely that steering away will occur. Although adolescence is another transitional opportunity, such children are at risk for affiliation with deviant peers. In fact, Dodge and Pettit provided evidence that such children react psychophysiologically in ways that make it uncomfortable for them to interact with typical peers.89 At this point, other cognitive strategies also play a role (e.g., the greater likelihood of hostile attributions). Movement toward a diagnosis of conduct disorder is overdetermined in such adolescents; the probability of such an outcome increases rapidly with age because of a confluence of multiple contributing factors.

In describing a developmental psychopathology model of depression, Hammen argued that cognitive vulnerabilities (e.g., negative view of self and negative self-schema) may be developed over time as a consequence of problematic relations and attachments with parents. Such cognitions make affected individuals more vulnerable to subsequent stressors, depression being the eventual outcome.123 Interestingly, Hammen provided evidence that depression-prone individuals are also more likely to generate new stressors or exacerbate existing ones, thus fueling the cycle123 (see Petersen et al for a similar perspective on adolescent depression124).

From a clinical perspective, understanding factors that contribute to the onset and/or maintenance of psychopathology informs preventive interventions, as well as the need to involve families in the implementation of these interventions. Research has demonstrated that, beginning in infancy, children with difficult temperaments are at risk for negative or harsh parenting. Early identification of difficult temperament then becomes a critical time point for clinician intervention. At this stage, pediatricians have the opportunity to intervene and provide support to parents in order to prevent the onset of conduct problems. Suppose that this early opportunity is missed. The transition into elementary school can then become stressful for the child and lead to difficulties with peer interactions. However, the clinician can act to prevent the maintenance of psychopathological behavior by engaging the family in the process of intervention. The earlier a clinician can identify risk for pathological behavior, the sooner the opportunity for prevention or intervention occurs, which in turn, provides the child with the most opportunities to master developmental transitions successfully.