The Yeasts

1. Explain the etiology and epidemiology of Candida, Cryptococcus, Trichosporon, and Malassezia spp.

2. Describe the macroscopic phenotypes and microscopic structures used to identify yeasts.

3. Differentiate yeast species based on microscopic, macroscopic, and biochemical test results.

4. Compare and contrast the methods used to identify yeasts, including staining, antigen testing, and biochemical and growth characteristics (i.e., morphology).

5. Diagram an algorithm for identifying the yeasts discussed in this chapter.

General Characteristics

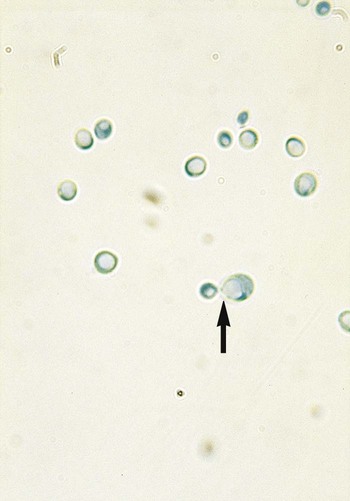

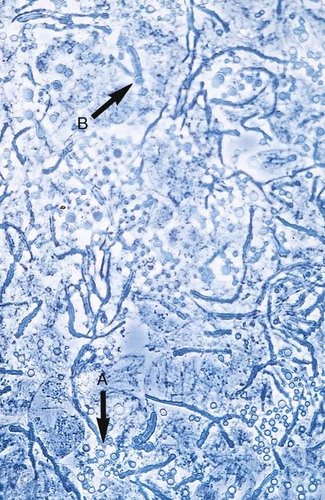

In general, the yeasts reproduce asexually by blastoconidia formation (budding) (Figure 63-1) and sexually by the production of ascospores or basidiospores. The process of budding begins with a weakening and subsequent outpouching of the yeast cell wall. This process continues until the bud, or daughter cell, is completely formed. The cytoplasm of the bud is contiguous with the cytoplasm for the original cell. Finally, a cell wall septum is created between mother and daughter yeast cells. The daughter cell often eventually detaches from the mother cell, and a residual defect occurs at the budding site (i.e., a bud scar).

With certain environmental stimuli, yeast can produce different morphologies. An outpouching of the cell wall that becomes tubular and does not have a constriction at its base is called a germ tube; it represents the initial stage of true hyphae formation (Figure 63-2). Alternatively, if buds elongate, fail to dissociate, and form subsequent buds, pseudohyphae are formed; to some, these resemble links of sausage (Figure 63-3). Pseudohyphae have cell wall constrictions rather than true intracellular septations delineating the fungal cell borders.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Specimen Collection, Transport, and Processing

Stains

Candida spp.

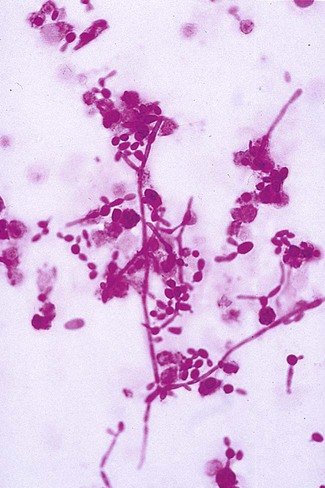

Direct microscopic examination of clinical specimens containing Candida organisms reveals budding yeast cells (blastoconidia) 2 to 4 μm in diameter and/or pseudohyphae (Figure 63-4) showing regular points of constriction, resembling links of sausage. True septate hyphae (filamentation) may also be produced by C. albicans and C. dubliniensis. The blastoconidia, hyphae, and pseudohyphae are strongly gram positive. The approximate number of such forms should be reported, because the presence of large numbers in a fresh clinical specimen may have diagnostic significance. Microscopically C. glabrata blastoconidia are notably smaller (at 1 to 4 µm) than those of other medically significant Candida spp.

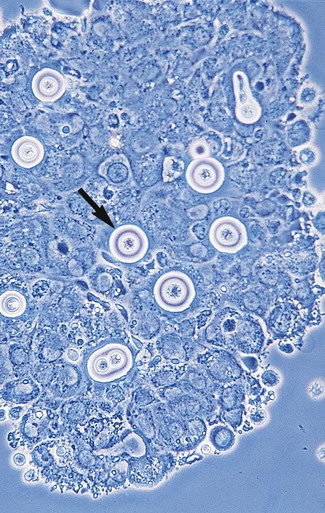

Cryptococcus spp.

Microscopic examination of other clinical specimens, including respiratory secretions, can be valuable for making a diagnosis of cryptococcosis. C. neoformans appears as a spherical, single or multiple budding, thick-walled yeast 2 to 15 μm in diameter. It usually is surrounded by a wide, refractile polysaccharide capsule (Figure 63-5). Perhaps the most important characteristic of C. neoformans is the extreme variation in the size of the yeast cells; this is unrelated to the amount of polysaccharide capsule present. It is important to remember that not all isolates of C. neoformans exhibit a discernible capsule.

Trichosporon spp.

Microscopic examination of clinical specimens that contain Trichosporon spp. reveals hyaline hyphae, numerous round to rectangular arthroconidia, and occasionally a few blastoconidia. Usually hyphae and arthroconidia predominate. In white piedra, white nodules are removed and observed using the potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation after light pressure is applied to the coverslip to crush the nodule. Hyaline hyphae 2 to 4 μm wide and arthroconidia are found in the preparation of the cementlike material that binds the hyphae together. The organism may be identified in culture by the presence of true hyphae, blastoconidia, and arthroconidia in conjunction with a positive urease (see Figure 60-40). Although Trichosporon asahii may be distinguished from other Trichosporon species by its biophysical profile (carbohydrate and substrate utilization), these organisms are likely best distinguished at the species level with molecular tools, such as DNA sequencing.

Malassezia spp.

M. furfur most often is detected through direct microscopic examination of skin scrapings. The organism is easily recognized as oval- or bottle-shaped cells that exhibit monopolar budding in the presence of a cell wall with a septum at the site of the bud scar. Small hyphal fragments also are observed (Figure 63-6); the morphology is commonly described as “spaghetti and meatballs.” In cases of fungemia, the morphologic form seen in direct examination of blood cultures is small yeasts without the presence of pseudohyphae.

Cultivation

Cryptococcus spp.

Colonies of C. neoformans usually appear on culture media within 1 to 5 days. The growth begins as a smooth, white to tan colony that may be mucoid to creamy (Figure 63-7). It is important to recognize the colonial morphology on different culture media, because variation does occur; for example, on inhibitory mold agar, C. neoformans appears as a golden yellow, nonmucoid colony. Textbooks typically characterize the colonial morphology as being Klebsiella-like because of the large amount of polysaccharide capsule material present. In reality, most isolates of C. neoformans do not have large capsules and may not have the typical mucoid appearance.

Approach to Identification

Candida spp.

C. albicans may be identified by the production of germ tubes or chlamydoconidia (Figure 63-8; also see Figure 63-2). Other Candida spp. are most commonly identified by the utilization of specific substrates and the fermentation or assimilation of particular carbohydrates. For instance, C. glabrata ferments and assimilates only glucose and trehalose, whereas C. tropicalis ferments and assimilates sucrose and maltose. Another method of identifying C. albicans and differentiating it from other Candida spp. is based on the presence of chlamydoconidia (see Figure 63-8) on cornmeal agar containing 1% Tween 80 and trypan blue incubated at room temperature for 24 to 48 hours. (Many of the finer points of yeast identification are discussed in The Yeasts: A Taxonomic Study, by Kreger-Van Rij.) The morphologic features of yeasts on cornmeal agar containing Tween 80 often allow for tentative identification of selected species and, an important benefit, may detect misidentifications by commercial systems (Table 63-1).

TABLE 63-1

Characteristic Microscopic Features of Commonly Encountered Yeasts on Cornmeal Tween 80 Agar

| Organism | Arthroconidia/Blastoconidia | Pseudohyphae or Hyphae |

| Candida albicans | Spherical clusters at regular intervals on pseudohyphae | Chlamydoconidia present on hyphae |

| Candida glabrata | Small, spherical, and tightly compacted | None produced |

| Candida krusei | Elongated; clusters occur at septa of pseudohyphae | Branched pseudohyphae |

| Candida parapsilosis | Present but not characteristic | Sagebrush or “shaggy star” appearance; large (giant) hyphae present |

| Candida kefyr (pseudotropicalis) | Elongated, lie parallel to pseudohyphae | Pseudohyphae present but not characteristic |

| Candida tropicalis | Produced randomly along hyphae or pseudohyphae | Pseudohyphae present but not characteristic |

| Cryptococcus spp. | Round to oval, vary in size, separated by a capsule | Rare; usually not seen |

| Saccharomyces spp. | Large and spherical | Rudimentary hyphae sometimes present |

| Trichosporon spp. | Numerous, resemble Geotrichum spp.; septate hyphae present | May be present but difficult to find |

Germ Tube Test

The germ tube test (see Procedure 63-1 on the Evolve site) is the most generally accepted and economical method used in the clinical laboratory to identify yeasts. Approximately 75% of the yeasts recovered from clinical specimens are C. albicans, and the germ tube test usually provides sufficient identification of this organism within 3 hours.

Germ tubes appear as early hyphal-like extensions of yeast cells that are produced without a constriction at the point of origin from the yeast cell (see Figure 63-2). Another Candida species, C. dubliniensis, has been shown to also produce true germ tubes. Although C. dubliniensis is infrequently encountered, supplemental biochemical or morphologic testing may be needed to differentiate it from C. albicans. C. tropicalis produces what has been called “pseudo-germ tubes,” which are constricted at the base or point of germ tube origin from the yeast cell. Unless this is recognized and the laboratorian has developed the skills to distinguish between true germ tubes and pseudo-germ tubes, C. tropicalis isolates will be misidentified as C. albicans.

Cryptococcus neoformans

Microscopic examination of colonies of C. neoformans may be helpful for providing a tentative identification of C. neoformans, because the cells are spherical and vary considerably in size. A presumptive identification of C. neoformans may be based on rapid urease production and failure to utilize an inorganic nitrate substrate. Final identification of C. neoformans usually is based on typical substrate utilization patterns and, in some laboratories, pigment production on niger seed (thistle or birdseed) agar (Figure 63-9). Immunocompromised patients suffering from infection die each year, with an estimated 500,000 in Africa alone. Diagnosis is typically made by identifying the encapsulated yeast in the spinal fluid using India ink. The use of serological techniques for the detection of the cryptococcal polysaccharide capsule glucuronoxylamannan (GXM) may be completed using latex agglutination or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). A recent study demonstrated that plasma and urine can be used to identify cryptococcal antigen, thereby eliminating the need for the invasive spinal tap. The use of alternate specimens has the potential to improve screening of patients infected with HIV and reduced CD4 lymphocyte counts before the exacerbation of symptoms, which may not be apparent early enough for successful treatment of the infection. Additional tests useful for identifying C. neoformans and other species of cryptococci are discussed later in the chapter.

Rapid Urease Test

The rapid urease test (see Procedure 63-2 on the Evolve site) is a most useful tool for screening for urease-producing yeasts recovered from respiratory secretions and other clinical specimens. Alternatives to this method include use of a heavy inoculum of the tip of a slant of Christensen’s urea agar and subsequent incubation at 35° to 37°C. In many instances, a positive reaction occurs within several hours; however, 1 to 2 days of incubation may be required. Interestingly, strains of Rhodotorula spp., some Candida spp., and Trichosporon spp. hydrolyze urea with time, so a distinction should be made between a traditional urease test, which takes hours, and the rapid urease test.

The microscopic morphologic features of the yeast in question are helpful for interpreting the usefulness of the traditional urease test. An alternative to traditional urease testing is the rapid selective urease test (see Procedure 63-3 on the Evolve site). This method appears to be useful for rapidly detecting C. neoformans. These screening tests are helpful for making a presumptive identification of C. neoformans. When inoculum is limited, the laboratorian must use tests that can be performed and then prepare a subculture so that additional tests can be performed later. Often, inoculating the organism onto the surface of a plate of niger seed agar is just as fast, and results may be obtained during the same day of incubation at 25°C (this is discussed later in this section).

Commercially Available Yeast Identification Systems

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-Flight (MALDI-TOF)

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) is emerging as a potential rapid technique for the identification of yeast and fungal isolates within the microbiology laboratory. See Chapter 7 for more information. MALDI-TOF requires that isolates be cultured overnight and then processed using a standardized extraction procedure. Several studies report the correct identification of yeast to the species level up to approximately 98% in comparison to traditional culture methods. In addition, some laboratories have required the direct isolation of organisms from blood culture systems without subculturing to another medium to facilitate identification. Evidence suggests that MALDI-TOF is able to resolve species discrepancies more accurately than traditional culture methods and will reduce the time needed to identify an organism significantly.

Conventional Yeast Identification Methods

Cornmeal Agar Morphology

The second major step in this practical identification schema is to use cornmeal agar morphology as a means to determine whether the yeast produces blastoconidia, arthroconidia, pseudohyphae, true hyphae, and/or chlamydoconidia (see Procedure 63-4 on the Evolve site). Cornmeal agar morphology can be used to detect characteristic chlamydoconidia produced by C. albicans. This method currently is satisfactory for definitive identification of C. albicans when the germ tube test is negative. In other instances, microscopic morphologic features on cornmeal agar help differentiate the genera Cryptococcus, Saccharomyces, Candida, Geotrichum, and Trichosporon. Previously, it was believed that the morphologic features of the common Candida spp. were distinct enough to provide a presumptive identification. This can be accomplished for C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and C. kefyr, keeping in mind that numerous other species, uncommonly recovered in the clinical laboratory, might resemble microscopically any of the previously mentioned species. In general, this method performs well, because the previously mentioned genera and species are more commonly seen in clinical laboratories.

Carbohydrate Utilization

Carbohydrate utilization patterns are the most commonly used conventional methods for definitive identification of yeasts recovered in a clinical laboratory. Various methods have been advocated for use in determining carbohydrate utilization patterns by clinically important yeasts, and all work equally well. Procedure 63-5, which can be found on the Evolve site, outlines the method previously found to be most useful by the Mayo Clinic Mycology Laboratory; however, this method is not commonly used in clinical laboratories. Most use commercially available methods.

Phenoloxidase Detection Using Niger Seed Agar

Use of a simplified Guizotia abyssinica (niger seed) medium is a definitive method for detecting phenoloxidase production by yeasts (see Procedure 63-6 on the Evolve site). Most isolates of C. neoformans readily produce phenoloxidase; however, some do not. In addition, in some instances, cultures of C. neoformans have been shown to contain both phenoloxidase-producing and phenoloxidase-deficient colonies in the same culture.

1. Which of the following is not a virulence factor of Candida spp.?

2. Which method has improved the isolation of Candida spp. from positive blood cultures?

3. The specimen needed to isolate Trichosporon spp. is:

4. Germ tube formation is seen with which two yeasts?

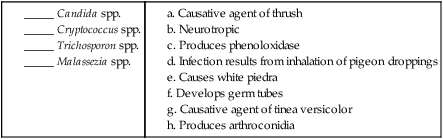

5. Matching: Match each description in the right-hand column with the correct organism in the left-hand column. More than one answer may be correct.

-inch apart at a 45-degree angle to the culture medium. A sterile coverslip may be added to one area.

-inch apart at a 45-degree angle to the culture medium. A sterile coverslip may be added to one area.