15 The upper arm and elbow

Apart from injury, disorders of the upper arm and elbow region are generally straightforward and present few special problems. They conform to the general descriptions of bone and joint diseases that were given in Part 2. Thus the humerus is subject to the ordinary infections of bone, and occasionally to bone tumours – especially metastatic tumours. The elbow is liable to every type of arthritis, none is particularly common though rheumatoid arthritis is commoner than osteoarthritis. After the knee, it is the joint most often affected by osteochondritis dissecans and loose body formation. The ulnar nerve lies in a vulnerable position at the back of the medial epicondyle, and the possibility of impairment of nerve function complicating disease or injury of the joint should always be remembered. Replacement arthroplasty of the elbow is undertaken increasingly, but compared with those of hip and knee arthroplasty the results still leave much to be desired, especially from the point of view of the longevity of the new joint.

SPECIAL POINTS IN THE INVESTIGATION OF UPPER ARM AND ELBOW SYMPTOMS

History

The interrogation follows the usual lines suggested in Chapter 1. It is important to ascertain the exact site and distribution of the pain, and its nature. Pain arising locally in the humerus is easily confused with pain arising in the shoulder, which characteristically radiates to a point about half-way down the outer aspect of the upper arm. Elbow pain is localised fairly precisely to the joint, though a diffuse aching pain is often felt also in the forearm. When the ulnar nerve is interfered with behind the elbow the symptoms are mainly in the hand.

Steps in routine examination

A suggested plan for the routine clinical examination of the upper arm and elbow is summarised in Table 15.1.

Table 15.1 Routine clinical examination in suspected disorders of the upper arm and elbow

| 1. LOCAL EXAMINATION OF THE ARM AND ELBOW | |

| Inspection | Power |

| Bone contours and alignment | Flexors |

| Soft-tissue contours | Extensors |

| Colour and texture of skin | Supinators |

| Scars or sinuses | Pronators |

| Palpation | Stability |

| Skin temperature | Lateral ligament |

| Bone contours | Medial ligament |

| Soft-tissue contours | The median nerve |

| Local tenderness | Sensory function |

| Movements (active and passive) | Motor function (opponens action) |

| Humero-ulnar joint: | Sweating |

| Flexion | The radial nerve |

| Extension | Sensory function |

| Radio-ulnar joint: | Motor function (extension of wrist, thumb, and fingers) |

| Supination | The ulnar nerve |

| Pronation | Sensory function |

| ? Pain on movement | Motor function |

| ? Crepitation on movement | Sweating |

| 2. EXAMINATION OF POTENTIAL EXTRINSIC SOURCES OF ARM PAIN | |

Movements at the elbow

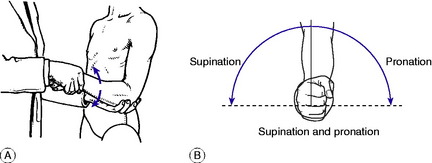

The elbow joint has two distinct components: the hinge joint between the humerus above and the ulna and radius below, allowing flexion–extension movement; and the pivot joint between the upper ends of the radius and ulna, allowing rotation of the forearm. It should be remembered that free rotation of the forearm is dependent not only upon an intact superior radio-ulnar joint: it demands also free mobility between the radius and ulna throughout their length, and distally at the inferior radio-ulnar joint. Flexion–extension: The normal range is from 0 to 155 ° (0 = anatomical position, with the arm straight). Supination–pronation: Rotation movements must be tested with the elbow flexed to a right angle, to eliminate rotation at the shoulder (Fig. 15.1A). The normal range is 90 ° of supination (palm up) and 90 ° of pronation (palm down) (Fig. 15.1B). If the range of rotation is restricted possible causes must be sought in the forearm and wrist as well as in the elbow.

The ulnar nerve

Because of the vulnerability of the ulnar nerve in its course behind the elbow, tests of ulnar nerve function should be carried out as part of the routine examination of the elbow. Examine for sensibility in the little finger and medial half of the ring finger, and test the ulnar-innervated small muscles of the hand for wasting or weakness: a simple test is to ask the patient to spread the fingers and to bring them together again forcibly, to prevent a card gripped between the middle and ring fingers from being withdrawn. Note whether the skin in the territory of the ulnar nerve sweats equally with the rest of the hand.

Extrinsic sources of pain in the upper arm

Pain in the upper arm is commonly referred from a lesion elsewhere—particularly from the shoulder, and from the neck when the brachial plexus or its roots are involved. Shoulder pain usually radiates from the tip of the acromion process to about the middle of the outer aspect of the arm, but it does not extend below the elbow. In contrast, nerve pain from interference with the brachial plexus often extends throughout the length of the arm and forearm into the hand and fingers; and frequently there is accompanying paraesthesiae in the form of tingling, numbness, or ‘pins and needles’.

DISORDERS OF THE UPPER ARM

ACUTE OSTEOMYELITIS (General description of acute osteomyelitis, p. 85)

Pathology. Except in time of war the humerus is seldom infected directly by organisms introduced from without, for compound fractures are rare. Infection is usually haematogenous, from a focus elsewhere in the body. This type of infection occurs mainly in children, and it usually begins in a metaphysis of the bone – more often the upper metaphysis than the lower. Since both the upper and the lower metaphyses are partly enclosed within the capsule of the shoulder and of the elbow respectively, a metaphysial infection is liable to spread directly to the adjacent joint, causing pyogenic arthritis (see Fig. 7.2).

Imaging. Radiographs do not show any abnormality at first. After about two weeks there are often localised rarefaction and subperiosteal new bone formation (Fig. 15.2), but these changes may be slight at first. Radioisotope scanning shows increased uptake in the affected area.

Investigations and treatment are the same as for acute osteomyelitis elsewhere (p. 89).

TUMOURS OF BONE

Benign tumours (General description of benign bone tumours, p. 106)

Giant-cell tumour is uncommon in the humerus, but when it does occur the usual site is at the upper end, where it often extends close up to the articular surface. The tumour occurs chiefly in young adults, and its general characteristics are like those of giant-cell tumour of bone at other sites (p. 109).

Malignant tumours (General description of malignant bone tumours, p. 112)

Metastatic tumours

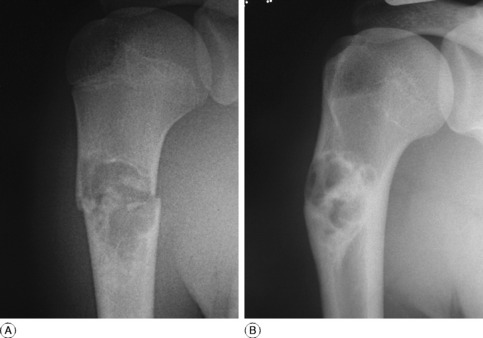

Metastatic tumours, by comparison, are common, especially in the proximal part of the humerus (Fig. 15.3). Carcinomatous deposits from tumours of the lung, breast, prostate, kidney, and thyroid are common and usually occur near the upper end of the shaft, where there is much vascular marrow. Such metastases are a common cause of pathological fracture and may require internal fixation as well as adjuvant treatment with radiotherapy.

BONE CYST

Both simple bone cysts and aneurysmal bone cysts can occur in the humerus and were described on page 126. The humerus is the commonest site of simple bone cyst, which occurs especially in children or adolescents, and at the upper end of the bone. The cyst replaces the normal bone structure and may lead to pathological fracture as the presenting symptom in over 50% of cases. (Fig. 15.4A). Small cysts may simply be kept under observation, since the majority heal spontaneously in adult life (Fig. 15.4B). A large cyst which might lead to fracture, should first be aspirated and injected with corticosteroid solution or autogenous bone marrow. Most fractures through cysts heal with conservative treatment and internal fixation is rarely required in the humerus.

DISORDERS OF THE ELBOW

CUBITUS VALGUS

The normal elbow, when fully extended, is in a position of slight valgus – usually 10 ° in men and 15 ° in women. This is known as the carrying angle. If the angle is increased, so that the forearm is abducted excessively in relation to the upper arm, the deformity is known as cubitus valgus (Fig. 15.5).

Fig. 15.5 Cubitus valgus (left elbow). The deformity predisposes to friction neuritis of the ulnar nerve.

Secondary effects. The most important sequel of cubitus valgus is interference with the function of the ulnar nerve. When valgus deformity is marked, the nerve is angled sharply round the prominent medial part of the joint, and repeated friction may lead to fibrosis of the nerve trunk. Symptoms develop insidiously over a long period: there are tingling and blunting of sensibility in the ulnar distribution in the hand, with weakness and wasting of the ulnar-innervated small hand muscles (p. 291).

PYOGENIC ARTHRITIS OF THE ELBOW (General description of pyogenic arthritis, p. 96)

The causation, pathology, clinical features and treatment of the condition are similar to other large joints and are described on page 97.

TUBERCULOUS ARTHRITIS OF THE ELBOW (General description of tuberculous arthritis, p. 98)

The pathological and clinical features of joint tuberculosis were described on page 98, and further description is not required here. Biopsy may be required to establish the diagnosis.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS OF THE ELBOW (General description of rheumatoid arthritis, p. 134)

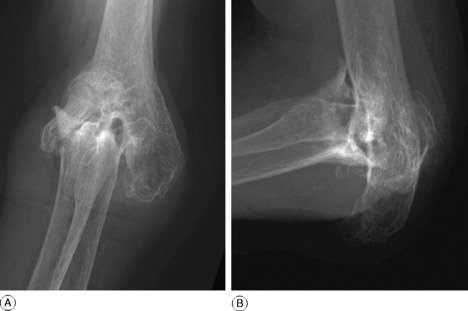

Imaging. Radiographic examination. At first there are no changes. Later, there is diffuse rarefaction in the area of the joint. In long-established cases the cartilage space is lost and there may be considerable erosion of the bone ends (Fig. 15.6).

Treatment. Primary treatment is along the lines suggested for rheumatoid arthritis in general (p. 137).

Operative treatment. If extensive destruction of the articular cartilage leads to persistent disabling pain with bone destruction and deformity, operation must be considered. If pain is largely at the lateral side of the joint the simple operation of excision of the head of the radius, with a limited synovectomy, often gives good relief. Replacement arthroplasty, by the fitting of a hinged prosthesis with long stems cemented into the humerus and ulna, has now been largely abandoned because of the risk of loosening and fracture. Improved results have been obtained by non-linked replacements of the articular surfaces with metal and plastic liners. The long’term functional results are not as good as with hip and knee replacements, but offer satisfactory pain relief.

OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE ELBOW (General description of osteoarthritis, p. 140)

Radiographs show narrowing of the cartilage space and pointed osteophytes at the joint margins (Fig. 15.7). Loose bodies (formed from detached osteophytes or from flakes of articular cartilage) may be present.

NEUROPATHIC ARTHRITIS OF THE ELBOW (General description of neuropathic arthritis, p. 147)

Cause. The usual underlying cause of the disease in the elbow is syringomyelia, but any other affection that leads to loss of sensibility (e.g. diabetic neuropathy) may be responsible.

OSTEOCHONDRITIS DISSECANS OF THE ELBOW (General description of osteochondritis dissecans, p. 153)

After the knee, the elbow is the most frequent site of osteochondritis dissecans. The disorder is characterised by necrosis of part of the articular cartilage and of the underlying bone, with eventual separation of the fragment to form an intra-articular loose body (Fig. 15.8).

Imaging. Plain radiographs in the early stages show an area of irregularity on the affected subchondral bone, usually of the capitulum. Later a shallow cavity, whose margins are demarcated clearly from the bone within it, is seen (Fig. 15.8). Eventually the bony fragment separates from the cavity and lies free within the joint, usually in the lateral compartment. MR scanning in the earlier stages of the disease may be valuable in determining the possibility of operative treatment prior to separation of the bony fragment.

Treatment. If the fragment is small, operation is delayed until the fragment of bone and cartilage is ripe for separation or has actually separated. The fragment is then removed. If the fragment is large and is identified prior to separation it may be fixed in place with a fine screw or pin until fixation to the underlying bone occurs.

PATHOLOGY AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Osteochondritis dissecans was described on page 153 and osteoarthritis on page 140.

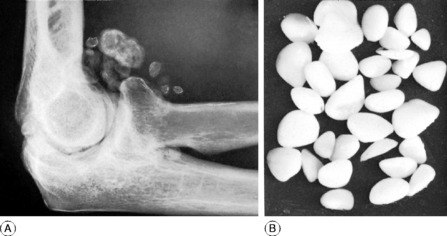

Synovial chondromatosis (osteochondromatosis). This is a rare disease of synovial membrane in which numerous synovial villi become pedunculated and transformed into cartilage; eventually they are detached to form a large number of loose bodies, many of which become calcified (Fig. 15.9).

The characteristic symptom of a freely movable loose body is sudden locking of the elbow during movement, with sharp pain. The joint is usually unlocked after an interval, either spontaneously or by the patient’s manoeuvres. Several hours later the joint swells because of effusion of fluid within it. The symptoms subside within a few days, but repeated attacks are to be expected.

Radiographs show the loose body or bodies (Fig. 15.9A) and usually indicate the nature of the primary condition.

TENNIS ELBOW (Lateral epicondylitis)

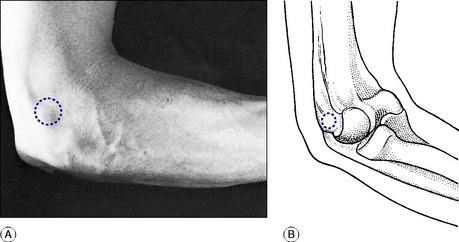

On examination there is tenderness precisely localised to the front of the lateral epicondyle of the humerus (Fig. 15.10). Pain is aggravated by putting the extensor muscles on the stretch—for example, by flexing the wrist and fingers with the forearm pronated. Movements of the elbow are full.

Conservative treatment. Where rest and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have failed to provide relief, injection of the muscle origin with local anaesthetic and hydrocortisone is frequently employed. Repeat injections may be required on one of two occasions, but usually give relief for up to 6 weeks. However, results from randomised trials with longer follow-up showed no greater improvement than achieved with other conservative measures. Orthotic devices, such as the proximal forearm band splint to reduce tension at the extensor origin are popular with those wishing to continue sporting activities, but their long-term benefit remains uncertain. Other local treatment modalities such as sonic shock wave therapy and eccentric strengthening exercises provide equally uncertain long-term results.

OLECRANON BURSITIS

The bursa behind the olecranon process is liable to traumatic bursitis, septic bursitis, and gout.

Traumatic bursitis. In traumatic bursitis (‘student’s elbow’) the bursa is distended with clear fluid (Fig. 15.11). Treatment at first should be by aspiration, followed by the injection of hydrocortisone into the bursa. If the swelling recurs the bursa should be excised.

FRICTION NEURITIS OF THE ULNAR NERVE

The ulnar nerve is vulnerable where it lies in the groove behind the medial epicondyle of the humerus. Its function may be interfered with either by constriction or by recurrent friction while in tension. Constriction is usually secondary to osteoarthritis, with encroachment of osteophytes upon the ulnar groove. Friction under tension occurs especially when the carrying angle of the elbow is increased (cubitus valgus, p. 282). This latter type is often a late sequel of a supracondylar fracture of the humerus sustained in childhood (‘tardy ulnar palsy’). In both cases the nerve undergoes fibrosis, and unless the mechanical fault is relieved without undue delay the changes may eventually become irreversible.