CHAPTER 32 The Ulnar-Shortening Osteotomy

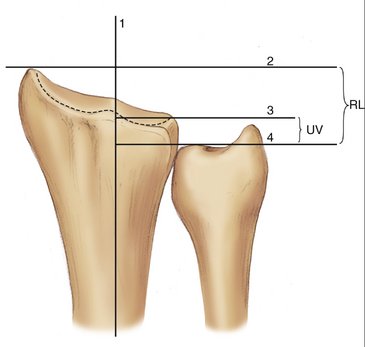

Vague complaints of pain stemming from seemingly innocuous events often make the diagnosis and treatment of ulnar-sided wrist ailments an exercise in frustration for both physicians and patients. Fortunately, widespread interest in the pathological conditions of the ulnar wrist has helped elucidate some of the more common conditions affecting this area. One such condition, often referred to as ulnocarpal abutment or the ulnocarpal impaction syndrome, occurs when excessive loads exist between the distal ulna and ulnar carpus. This overloading stems from the distal ulnar articular surface projecting more distal than the ulnar articular surface of the distal radius. This situation has been termed “ulnar-positive variance” with “ulnar variance” being defined as the difference in length between the distal ulnar corner of the radius and distalmost aspect of the dome of the ulnar head (Fig. 32-1). Ultimately, ulnar-positive variance combined with a lunotriquetral tear and a triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) tear make up the triad of ulnar impaction syndrome. Many procedures have been developed to alleviate this degenerative, often debilitating, condition, but the gold standard for correcting ulnar-positive variance is the ulnar-shortening osteotomy. The goals of the shortening procedure are to relieve pain and prevent arthritis by reestablishing a neutral or slightly negative ulnar variance.

Biomechanics of Ulnar Impaction Syndrome

Ulnar impaction syndrome is characterized by pain and swelling that typically develop in patients with excessive loading across the distal ulna. Generally, the radius receives 82% of the load borne through the wrist while the ulna receives 18% of the force. However, Palmer and Werner showed that loads through the distal ulna can change and are directly related to ulnar variance.1 Increasing ulnar length by 2.5 mm raises ulnar loads to 42%, whereas a decrease in length of 2.5 mm lowers the force seen at the distal ulna to 4.3%. Furthermore, these investigators reported that 73% of wrists with tears of the TFCC had either an ulnar-positive or ulnar-neutral variance, indicating that overloading of the ulnar wrist can ultimately lead to injury and degeneration of the TFCC.

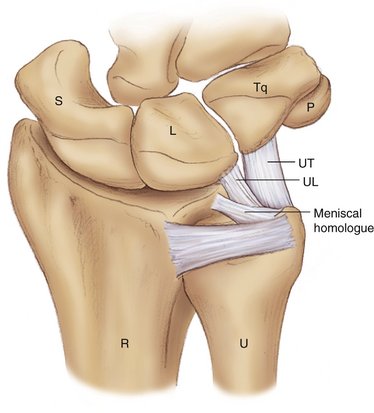

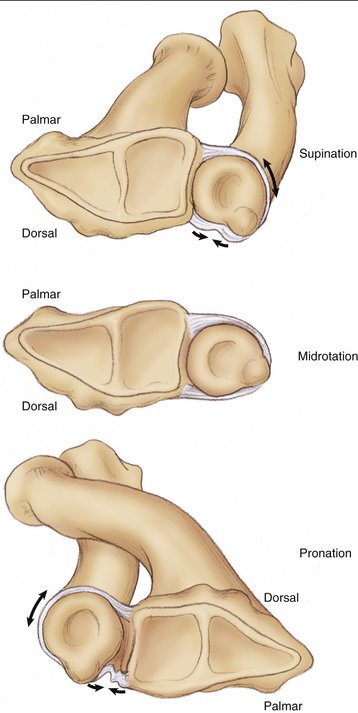

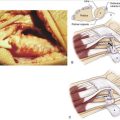

The “TFCC,” a term coined by Palmer and Werner in 1981,2 is a ligamentous and cartilaginous structure found between the distal ulna and ulnar carpus that, along with the bony architecture in this region, helps maintain the relationship of the distal ulna to the distal radius (Figs. 32-2 and 32-3). Strong volar and dorsal ligaments, termed the “dorsal and palmar radioulnar ligaments,” serve as a capsule surrounding the DRUJ. These ligaments continue onto the horizontal surface of the distal ulna, where they become thickened and serve as limbi for the TFCC. Ultimately, these ligaments go on to attach to the base of the ulnar styloid. Biomechanical studies have revealed a complex interplay between these ligaments and the motion that occurs at the DRUJ. DiTano and coworkers showed that the palmar radioulnar ligament becomes taut in supination, whereas the dorsal radioulnar ligament tightens with pronation (Fig. 32-4).3 This holds importance for different instability patterns that can occur at the DRUJ.

Historical Results of the Procedure

The first ulnar-shortening osteotomy was described by Milch in 1941.4 He elected to utilize the procedure on a 17-year-old patient who developed a painful ulnar-positive wrist from a distal radius malunion. Milch’s technique entailed resection of a portion of the ulnar shaft with wire fixation at the osteotomy site. Since this initial description, numerous authors have described various osteotomy types, including transverse,5,6 oblique (of varying degrees),6–10 sliding (long oblique),11 and step cut.12 Several commercially available systems have been developed to facilitate bony contact, compression, and rigid fixation at the osteotomy site.6,10,11

Attempting to elucidate which osteotomy provides both stability and rapid healing potential, while remaining easy to perform, can be an arduous task. Many authors have reported good results with any of the osteotomy methods just mentioned. In 1995, Wehbé and colleagues reported on their results for ulnar shortening utilizing a transverse osteotomy and the AO small distractor.5 In their 24 patients with ulnar impaction syndrome, they had no nonunions and an average time to healing of 9.7 weeks. They did have three delayed unions, but these reportedly healed without incident by 28, 34, and 36 weeks. It should be noted that their criteria for bony healing were quite stringent and if they had used criteria utilized by previous authors their delayed unions would have coalesced by 12, 16, and 20 weeks.

In 2005, Darlis and associates reported their results on 29 patients who underwent a step-cut osteotomy of the ulna for various pathological conditions.12 Average time to union was 8.3 weeks, and they had no delayed unions or nonunions. Although these authors deem this a simple technique, it does require more cuts than transverse or oblique osteotomies.

Many surgeons today prefer an oblique osteotomy based in large part on a 1993 study by Rayhack and associates.6 In that study, 23 transverse osteotomies in which a specialized external compression device was utilized were compared with 17 oblique osteotomies in which a cutting guide designed by the lead author was implemented. Average healing times for the transverse osteotomies was 21 weeks compared with 11 weeks for the group with the oblique osteotomies. Furthermore, one nonunion was noted for the transverse group. Importantly, Rayhack and associates also reported on the biomechanical differences between the two constructs. Cadaveric data revealed no significant difference between the oblique or transverse cuts in regard to anteroposterior or lateral bending strength. The oblique osteotomy was found, however, to be significantly stiffer in torsion.

Several authors utilizing different systems for performing oblique osteotomies have corroborated the excellent results demonstrated by Rayhack and associates. Reporting on 27 patients (30 osteotomies), Chun and Palmer described their results for the oblique osteotomy utilizing a freehand technique.7 The wrists were graded both preoperatively and postoperatively with a modified Gartland and Werley system.13 Preoperatively, 28 wrists were graded poor and 2 as fair. Postoperatively, 24 wrists were graded excellent with 4 good results, 1 fair result, and 1 poor result. There were no nonunions. Chen and Wolfe also reported good results for the oblique osteotomy utilizing a freehand technique and an AO compression device.8 Preoperatively, 14 wrists were graded fair and 4 poor whereas, postoperatively, 13 were graded excellent, 3 good, and 2 fair. They also had no nonunions. Most recently, Mizuseki and colleagues reported their results for 24 oblique osteotomies created by their own device.10 Healing time averaged 8.1 weeks, and they had no nonunions.

Trumble and colleagues combined arthroscopic repairs of the TFCC with ulnar-shortening osteotomies.14 Their patients regained 83% of their total range of motion and 81% of their grip strength when compared with the contralateral side. In 19 of 21 patients, pain symptoms improved from complaints of pain even with routine activities to having complete relief of pain with all activities postoperatively. The other two patients had decreased levels of pain after surgery but continued to have occasional discomfort with some heavy activities.

Surgical Technique

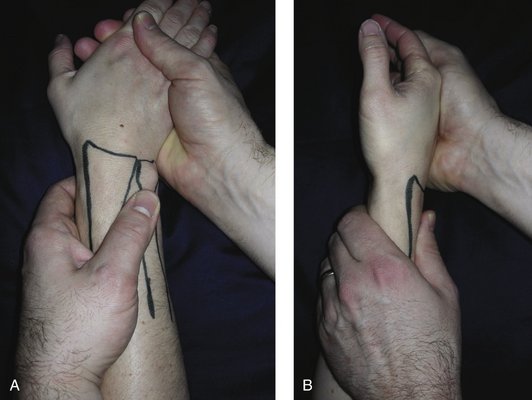

The typical patient who benefits from an ulnar-shortening osteotomy relates a history of ulnar-sided wrist pain that is exacerbated by pronation/supination activities and forceful grip. On examination many patients will have swelling and tenderness localized to the TFCC and distal ulna (Fig. 32-5). The ulnar impaction maneuver, performed by moving the distal ulna in a volar and dorsal direction with the wrist in ulnar deviation, can help elicit pain that stems from the TFCC and ulnar impaction (Fig. 32-6). Another valuable examination maneuver is the ulnar stress test as described by Nakamura and colleagues.15 This test is considered positive when pain is elicited by axially loading, flexing, and extending a patient’s pronated and ulnarly deviated wrist. The “fovea test” is performed by asking the patient to flex the wrist. This allows palpation of the FCU, which facilitates locating the fovea of the TFCC—between the flexor carpi ulnaris and ulnar styloid process. Exclusion of other sources of discomfort, such as pisotriquetral arthritis, DRUJ instability or arthritis, or extensor carpi ulnaris tendinitis or hypermobility heightens the suspicion for a pathological process of the TFCC. Plain radiographs, including posteroanterior and lateral views, should be obtained on every patient. Not only do these help determine the amount of shortening that will be required, but they also help determine if there are any other conditions (i.e., lunotriquetral instability/degeneration) that may need to be addressed. Importantly, one must obtain a true posteroanterior view of the wrist with the shoulder abducted to 90 degrees, elbow flexed to 90 degrees, and wrist in neutral rotation. The significance of a true posteroanterior view stems from the fact that rotation at the wrist can increase (pronation) or decrease (supination) ulnar variance. With this in mind, a posteroanterior view of a pronated wrist can be helpful in patients who develop pain during activities that require pronation (i.e., hammering, typing). These patients may not be experiencing symptoms until their ulnar variance becomes positive with pronation.16 Plain radiographs of the contralateral wrist may be helpful for determining the amount one wants to shorten the ulna. Contralateral views are not as useful, however, when that wrist is also ulnar positive. Magnetic resonance imaging or arthrography may be a reasonable adjunct to the radiographic evaluation when the surgeon suspects an acute tear of the TFCC that possibly can be repaired.

Whenever possible the plate should be applied to the volar surface of the ulna (Fig. 32-7). Not only is there more soft tissue padding, but this side also tends to be the flattest surface of the ulna, allowing for the best plate-to-bone contact. If the volar surface is not practical, then the surgeon should choose the flattest side that is still amenable to adequate soft tissue coverage. Occasionally, it is necessary to utilize plate benders to contour the plate to account for variations in ulnar shape. Plates can also be bent to overcompensate for the normal curvature of the ulna. This will help prevent gapping at the osteotomy site at the time compression is applied.

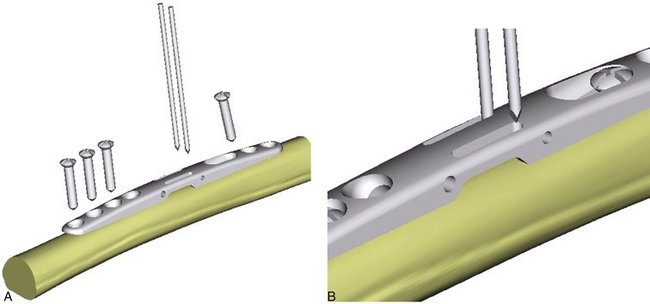

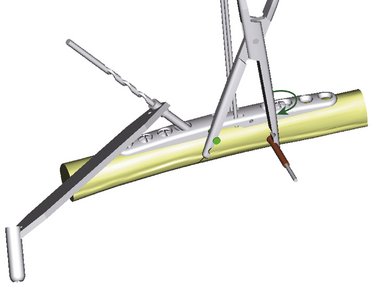

The plate is provisionally secured to the ulna with the help of the ulnar plate clamp. Using the 2.3-mm drill bit, 3.2-mm diameter self-tapping screws are used to fix the plate to the ulna on the same side as the lag screw. When dealing with brittle bone, the 2.3-mm drill holes can be tapped to precut screw threads. A fourth screw is placed in the slotted screw hole to affix the plate both proximal and distal to the planned osteotomy site. This screw should be placed at the end of the slot farthest from the lag screw. This allows for compression after the osteotomy is completed. At this point the combination pin/drill guide is applied. Two 0.062-inch Kirschner wires (K-wires) are placed in the slots of the guide that are away from the lag screw hole (Fig. 32-8). The shorter (50 mm) K-wire is placed first, followed by the longer (100 mm) wire. The differing K-wire lengths and the guide ensure the pins will remain parallel during insertion. The pin/drill guide is now removed.

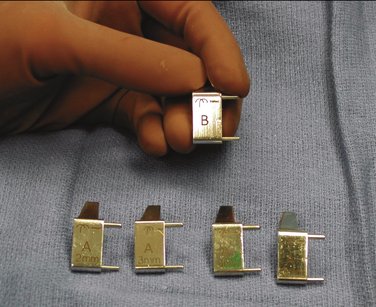

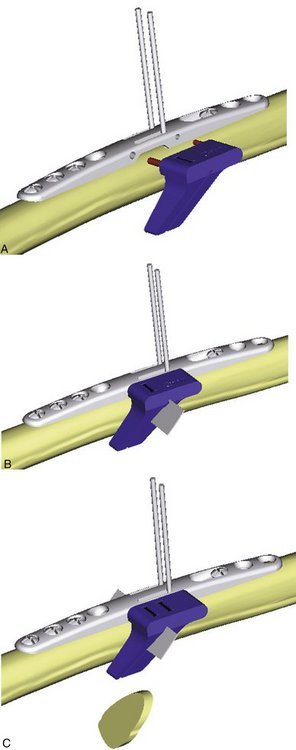

Correlating to measurements made from preoperative radiographs for ulnar variance, a cutting guide is selected for the intended amount of resection (2 to 5 mm). Marked “A” and “B,” these cutting guides are designed with pegs that can only be inserted so that the osteotomy cuts are made perpendicular to the path of the planned lag screw. Guide A is placed first. This guide defines the width of the osteotomy and is marked as either A-2, 3, 4, or 5 mm (Fig. 32-9). Five millimeters is usually the maximum correction required, but it can be more in certain trauma situations. After placing baby Hohmann retractors around the ulna to protect the adjacent soft tissues, the osteotomy is completed. Use of saline irrigation is recommend to cool the saw blade and prevent thermal injury. Guide A is then replaced with the finish cutting guide B. Once the sequential osteotomies have been completed the bone wafer is detached from its soft tissue attachments and excised (Fig. 32-10). Of paramount importance for the procedure is to keep the plate firmly fixed to the ulna to ensure parallel osteotomy cuts. Therefore, screws should be checked during the osteotomy and retightened as necessary to prevent plate slippage.

The peg of the bone compression clamp is inserted into the side of the plate. The cannulated portion of the clamp is then used as a drill guide to place a third 0.062-inch K-wire low on the bone between the slotted hole and the two parallel K-wires previously inserted. The position of this third wire creates compression forces perpendicular to the osteotomy. The screw in the slotted hole is then loosened to allow compression at the osteotomy using the bone compression clamp (Fig. 32-11). Once compression has been achieved, the slot screw should be retightened. At this time radiographs should be obtained to determine if the ulnar variance has been corrected to neutral or slightly negative. It is important to check that plate contact has not changed due to a changing radius of curvature of the ulna from shortening. If this does occur, the plate may need to be bent a second time to afford better conformity and plate contact.

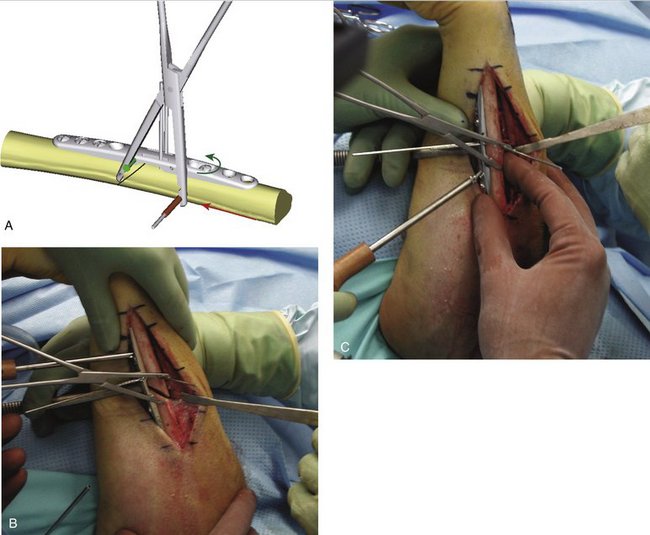

To insert the lag screw the pin/drill guide can be reapplied or the surgeon can choose to drill the hole freehand. A 3.2-mm drill bit is used first for the near cortex (Fig. 32-12). This is followed by the 2.3-mm drill bit, which is sent through the far cortex. The lag screw should be tapped to guarantee good purchase of the screw threads. A lag screw of appropriate length (normally 18 to 20 mm) is inserted. The final two screws adjacent to the slotted hole are inserted, followed by removal of the drill guide, compression clamp, and three K-wires. Final radiographs should be obtained to ensure proper screw lengths (Fig. 32-13).

FIGURE 32-13 A, Preoperative radiographs show ulnar-positive variance in a patient with a long-standing history of ulnar-sided wrist pain. Postoperative anteroposterior (B) and lateral (C) views illustrating a healed osteotomy and ulnar-negative variance.

Patients are seen at 2 weeks for their first postoperative visit when sutures are removed. Compliant patients are fitted with a removable long arm splint fabricated by one of our hand therapists. This allows for removal during showers and commencement of elbow flexion and extension exercises. Noncompliant patients are placed into a long arm cast. At 6 weeks, radiographs are obtained and gentle wrist range of motion exercises are started if there are early signs of bony consolidation. If there are more signs of bony union at 9 weeks, then the patients are instructed to begin gentle strengthening exercises.

Complications

In a properly performed osteotomy the complications are minimal. The most commonly reported adverse outcome is hardware prominence and tenderness.8,10,12 In our series of 17 osteotomies we found that four patients ultimately required plate removal owing to ongoing problems with hardware prominence. Other possible complications include infection, delayed union, nonunion, and nerve palsies. In our patients we did not experience any of these situations. The risk of delayed or nonunions can be minimized by avoiding thermal injury during the osteotomy and ensuring good apposition and compression when securing the plate. Nerve palsies can be avoided by the careful placement of retractors during the osteotomy and plate placement. Furthermore, when incisions are made distal to the ulnar styloid, extreme care should be taken to identify and protect the dorsal sensory branch of the ulnar nerve as it courses from volar to dorsal.

Results

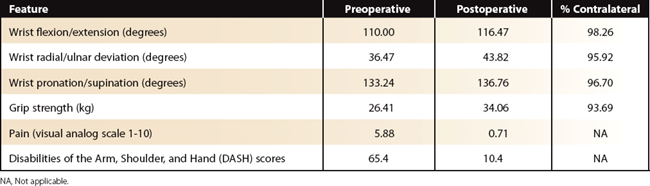

Seventeen patients were followed for a minimum of 12 months after undergoing shortening osteotomies with the Trimed system. Overall, the results were quite good, comparing favorably with other studies utilizing similar systems. Preoperative and postoperative range of motion, grip strength, pain, and Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) scores are tallied in Table 32-1. Bony union, defined as bridging of the trabecular bone and cortical margin blurring, was achieved at an average of 7.41 weeks. The average shortening was 4.12 mm.

1. Palmer AK, Werner FW. Biomechanics of the distal radioulnar joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 1984;187:26-35.

2. Palmer AK, Werner FW. The triangular fibrocartilage complex of the wrist—anatomy and function. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1981;6:153-162.

3. DiTano O, Trumble TE, Tencer AF. Biomechanical function of the distal radioulnar and ulnocarpal wrist ligaments. J Hand Surg [Am].. 2003;28:622-627.

4. Milch H. Cuff resection of the ulna for malunited Colles’ fracture. J Bone Joint Surg [Am].. 1941;23:311-313.

5. Wehbé MA, Mawr B, Cautilli DA. Ulnar shortening using the AO small distractor. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1995;20:959-963.

6. Rayhack JM, Gasser SI, Latta LL, et al. Precision oblique osteotomy for shortening of the ulna. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1993;18:908-918.

7. Chun S, Palmer AK. The ulnar impaction syndrome: follow-up of the ulnar shortening osteotomy. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1993;18:46-53.

8. Chen NC, Wolfe SW. Ulna shortening osteotomy using a compression device. J Hand Surg [Am].. 2003;28:88-93.

9. Labosky DA, Waggy CA. Oblique ulnar shortening osteotomy by a single saw cut. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1996;21:48-59.

10. Mizuseki T, Tsuge K, Ikuta Y. Precise ulna-shortening osteotomy with a new device. J Hand Surg [Am].. 2001;26:931-939.

11. Horn PC. Long ulnar sliding osteotomy. J Hand Surg [Am].. 2004;29:871-876.

12. Darlis NA, Ferraz IC, Kaufmann RW, et al. Step-cut ulnar-shortening osteotomy. J Hand Surg [Am].. 2005;30:943-948.

13. Gartland JJJr, Werley CW. Evaluation of healed Colles’ fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am.. 1981;63:895-907.

14. Trumble TE, Gilbert M, Vedder N. Ulnar shortening combined with arthroscopic repairs in the delayed management of triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1997;22:807-813.

15. Nakamura R, Horii E, Imaeda T, et al. The ulnocarpal stress test in the diagnosis of ulnar-sided wrist pain. J Hand Surg [Br].. 1997;22:719-723.

16. Minami K, Kato H. Ulnar shortening for triangular fibrocartilage complex tears associated with ulnar positive variance. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1998;23:904-908.