Chapter 8 The Thyroid

A. Generalities

The thyroid may not be the most important organ in a busy general practice, but in physical diagnosis it is second only to the heart in number of examination errors and lack of physician’s confidence. This is unfortunate, since better skills may guide a more intelligent use of costly scans and better assessment of the likelihood of hyperthyroidism in anxious young patients.

B. Anatomic Review And Thyroid Gland Inspection

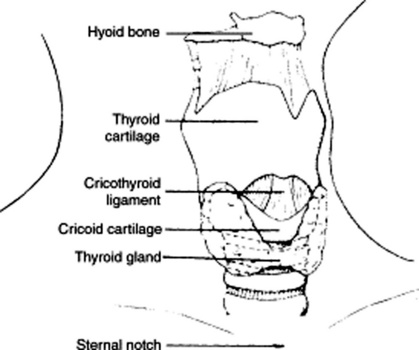

1 What are the thyroid’s landmarks?

They are the laryngeal prominence and cricoid cartilage. Start your exam by identifying the hyoid bone, a horseshoe mobile structure just under the mandible, so called because of its “upsilon” like shape. Immediately below it, you will find the thyroid cartilage, which can be readily identified by its V shape, the midline notch on the superior edge (laryngeal prominence), and its being the most prominent structure in the anterior neck (Adam’s apple). Just below it, separated by a little gap (the cricothyroid recess), is the horizontal ring of the cricoid cartilage. The thyroid isthmus lies immediately below, 4 cm from the laryngeal prominence. It connects the two lateral lobes of the gland by crossing the trachea over the second, third, and sometimes even the fourth ring. Note that while the distance between isthmus and landmarks (cricoid cartilage and laryngeal prominence) is constant in all individuals, the distance between laryngeal prominence and suprasternal notch is variable. This may result in glands that are either low lying or high lying in the neck (see Fig. 8-1).

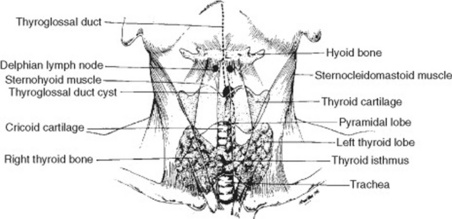

2 Where are the thyroid lobes in relation to other neck structures?

The lateral lobes fan out from the midline isthmus just below the cricoid cartilage, curve posteriorly around the sides of trachea and esophagus, and then ascend backwards and upward like the two branches of a V (Fig. 8-2). Each lobe is 3–5 cm long, so that the lower margin reaches down to 2 cm above the clavicle (and fifth to sixth tracheal ring), whereas the upper margin extends instead upward to the middle of the thyroid cartilage. Except for its isthmus, the thyroid is covered by thin, strap-like muscles, of which only the sternocleidomastoid muscles (SCMs) are visible. Since the fascial envelope of the gland is continuous with the pretracheal fascia of both the hyoid and cricoid, the isthmus will ascend and descend with the larynx upon swallowing. This is important because it helps in distinguishing the thyroid from other neck structures.

4 What is the best way to Inspect the thyroid?

It raises the trachea further up from the suprasternal notch, thus moving upward any low-lying thyroid, too.

It raises the trachea further up from the suprasternal notch, thus moving upward any low-lying thyroid, too.

It tightens the skin over the gland, thus enhancing visualization. Slight contralateral flexing of the neck also may accentuate a mass, nodule, or gland asymmetry.

It tightens the skin over the gland, thus enhancing visualization. Slight contralateral flexing of the neck also may accentuate a mass, nodule, or gland asymmetry.

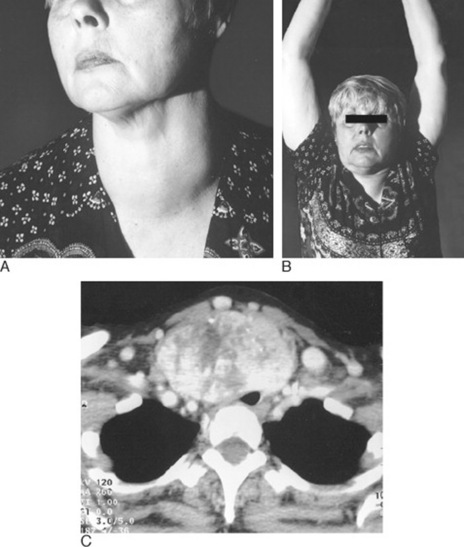

Once the patient is well positioned, inspect the midline, 2–3 cm above the clavicles. Look within the SCMs for the inferior margins of the thyroid lobes, and then locate the isthmus (just below the cricoid cartilage). Finally, inspect the superior margins of the lobes (which should barely touch the sides of the thyroid cartilage). Look also for any possible pyramidal lobe. Use cross-illumination with a penlight to better accentuate shadows and nodules. Observing the gland from the side also may help detect possible protrusions. Note that unless a goiter is present, there should be no bulging between cricoid cartilage and suprasternal notch. Hence, a goiter is effectively ruled out if the gland is not visible on lateral view of an extended neck. Once inspection is complete, assess the associated venous structures of the neck, and record any possible abnormality (Figs. 8-3 and 8-4).

5 How helpful is swallowing during inspection or palpation?

Swallowing modifies the shadows of thyroid irregularities or masses, thus enhancing their visual detection.

Swallowing modifies the shadows of thyroid irregularities or masses, thus enhancing their visual detection.

It raises the gland, thus making it more accessible to both inspection and palpation.

It raises the gland, thus making it more accessible to both inspection and palpation.

It slides the gland (or its irregularities) against the examiner’s hands, thus improving tactile discrimination and recognition.

It slides the gland (or its irregularities) against the examiner’s hands, thus improving tactile discrimination and recognition.

Most importantly, it allows the examiner to localize the abnormality because only the thyroid, lower trachea, and larynx move with swallowing. Deglutition lifts up both the trachea and thyroid by 1.5–3.5 cm. This movement culminates in a brief moment of hesitation, followed by a return of both the larynx and thyroid to their original location. Any mass that does not follow this triple sequence is not in the thyroid.

Most importantly, it allows the examiner to localize the abnormality because only the thyroid, lower trachea, and larynx move with swallowing. Deglutition lifts up both the trachea and thyroid by 1.5–3.5 cm. This movement culminates in a brief moment of hesitation, followed by a return of both the larynx and thyroid to their original location. Any mass that does not follow this triple sequence is not in the thyroid.

C. Thyroid Gland Palpation

13 How do you palpate a thyroid?

Start with proper positioning. In contrast to inspection, a slight ipsilateral flexion and rotation of the neck may allow you easier access to a mass, nodule, or gland asymmetry. Hence, to palpate the right lobe, ask the patient to flex and rotate the neck toward the right. Do the opposite for the left lobe. Yet, as for inspection, a slight neck extension (10 degrees) may help, too, by lifting the top of a substernal goiter into a more accessible position. Still, most experts recommend flexion over extension. Finally, ask the patient to swallow repeatedly while you palpate the moving gland.

Start with proper positioning. In contrast to inspection, a slight ipsilateral flexion and rotation of the neck may allow you easier access to a mass, nodule, or gland asymmetry. Hence, to palpate the right lobe, ask the patient to flex and rotate the neck toward the right. Do the opposite for the left lobe. Yet, as for inspection, a slight neck extension (10 degrees) may help, too, by lifting the top of a substernal goiter into a more accessible position. Still, most experts recommend flexion over extension. Finally, ask the patient to swallow repeatedly while you palpate the moving gland.

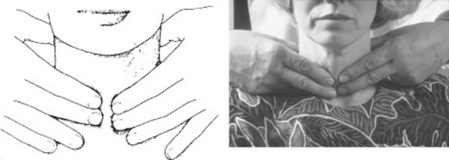

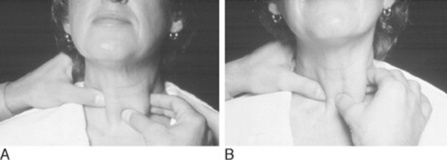

The posterior bimanual approach is the most commonly used. While standing behind the patient, place the index and middle fingers of both hands along the midline of the neck, just below the chin. These should be 2 cm above the suprasternal notch, and 0.5 cm inside the medial margin of the SCM. From that position, locate first the thyroid cartilage, then slide gently down to the horizontal groove that separates it from the cricoid cartilage. This is covered by the cricothyroid membrane, which overlies the first tracheal ring and represents the reference point for emergency tracheostomy (cricothyroidotomy) in upper airway obstruction. Continue sliding down until you reach the next well-defined tracheal ring. At this point, you are on the thyroid isthmus, which lies between the cricoid cartilage and suprasternal notch, and is almost never palpable. Slide your fingers laterally on the isthmus, and go around for approximately 2–3 cm along each side: you will be touching the two main lobes of the gland. Use a soft touch to minimize discomfort and maximize yield. If the gland is enlarged, evaluate its consistency. Then ask yourself whether the enlargement is asymmetric or bilateral, nodular or diffuse, with movable overlying layers associated with adenopathy. Use one hand to fix the trachea and the other to palpate one lobe at a time (Figs. 8-5 and 8-6). You can practice by placing the second and third fingers of both hands over your own sternal notch. Move them up 2 cm above the clavicles (toward the lower thyroid poles), then palpate each lobe in detail.

The posterior bimanual approach is the most commonly used. While standing behind the patient, place the index and middle fingers of both hands along the midline of the neck, just below the chin. These should be 2 cm above the suprasternal notch, and 0.5 cm inside the medial margin of the SCM. From that position, locate first the thyroid cartilage, then slide gently down to the horizontal groove that separates it from the cricoid cartilage. This is covered by the cricothyroid membrane, which overlies the first tracheal ring and represents the reference point for emergency tracheostomy (cricothyroidotomy) in upper airway obstruction. Continue sliding down until you reach the next well-defined tracheal ring. At this point, you are on the thyroid isthmus, which lies between the cricoid cartilage and suprasternal notch, and is almost never palpable. Slide your fingers laterally on the isthmus, and go around for approximately 2–3 cm along each side: you will be touching the two main lobes of the gland. Use a soft touch to minimize discomfort and maximize yield. If the gland is enlarged, evaluate its consistency. Then ask yourself whether the enlargement is asymmetric or bilateral, nodular or diffuse, with movable overlying layers associated with adenopathy. Use one hand to fix the trachea and the other to palpate one lobe at a time (Figs. 8-5 and 8-6). You can practice by placing the second and third fingers of both hands over your own sternal notch. Move them up 2 cm above the clavicles (toward the lower thyroid poles), then palpate each lobe in detail.

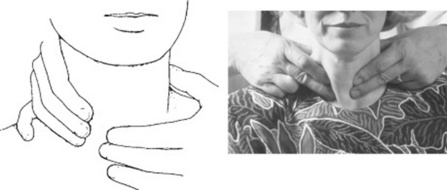

The anterior single-hand approach. Face the patient and use the thumb plus the index finger of one hand to palpate each lobe. Do this just inside the SCMs (Fig. 8-7).

The anterior single-hand approach. Face the patient and use the thumb plus the index finger of one hand to palpate each lobe. Do this just inside the SCMs (Fig. 8-7).

14 What are the normal variants in size and location?

Women have larger and more easily palpable glands.

Women have larger and more easily palpable glands.

In 1% of the population, the entire left lobe (or its lower half) is absent.

In 1% of the population, the entire left lobe (or its lower half) is absent.

The right lobe is often larger than the left.

The right lobe is often larger than the left.

A pyramidal lobe presents as a triangular projection, arising from the isthmus and extending up toward the hyoid. It feels like thyroid, and it moves with deglutition.

A pyramidal lobe presents as a triangular projection, arising from the isthmus and extending up toward the hyoid. It feels like thyroid, and it moves with deglutition.

Posterior, extracapsular, and ectopic tissue can occur in 5% of normal glands. This usually extends from the posterior aspect of the tongue toward the pyramidal lobe, and occasionally down into the mediastinum (see Chapter 6, Nose and Mouth, question 103).

Posterior, extracapsular, and ectopic tissue can occur in 5% of normal glands. This usually extends from the posterior aspect of the tongue toward the pyramidal lobe, and occasionally down into the mediastinum (see Chapter 6, Nose and Mouth, question 103).

D. Additional Components Of The Focused Thyroid Examination

17 What are the potential complications of a large goiter?

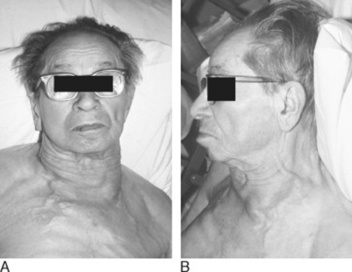

Mostly obstructive, with impaired venous return (facial plethora) and a compression of the esophagus and trachea that may result in dysphagia and dyspnea. Stridor occurs in 10% of substernal goiters; tracheal deviation in one third. Although Graves’ glands may be up to two times normal (i.e., 40 gm), multinodular goiters are usually the most prominent offenders. When a large mediastinal or substernal thyroid obstructs the superior vena cava, there will be venous engorgement over the anterior chest and neck and possible impairment of cerebral venous return (Fig. 8-8). If reversible, all these findings can be unmasked by the Pemberton’s maneuver.

18 What is the Pemberton’s maneuver?

A reversible superior vena cava (SVC) obstruction caused by a substernal goiter being “lifted” into the thoracic inlet as a result of arm raising. This makes the goiter behave like a “thyroid cork,” blocking the inlet and thus preventing venous return. To carry out the maneuver, ask the patient to elevate the arms above the level of the head, as if surrendering (“elevat[ing] both arms until they touch the sides of the head,” in Pemberton’s words). If the sign is present, “after a minute or so, congestion of the face, some cyanosis, and lastly distress become apparent.” In fact, the test is considered positive when the patient experiences either facial plethora (blue or pink suffusion of the neck and/or face due to venous stasis) or head congestion, dizziness, and stuffiness. If severe, the “thyroid cork” may even cause dyspnea and hypotension. The test is negative if nothing happens after 3 minutes of arm elevation (Fig. 8-9).

19 What is the significance of a positive Pemberton’s maneuver?

23 How do you distinguish a thyroid bruit from other neck sounds?

A venous hum is heard lower in the neck than a thyroid bruit. It is also suppressed by compression of the ipsilateral neck veins. Note that the continuous character of a “hum” cannot reliably differentiate it from a bruit, since 20–36% of all hyperthyroid patients have indeed a continuous bruit (due to arteriovenous communications within the hyperplastic gland). Compression of neck veins will help differentiate the two.

A venous hum is heard lower in the neck than a thyroid bruit. It is also suppressed by compression of the ipsilateral neck veins. Note that the continuous character of a “hum” cannot reliably differentiate it from a bruit, since 20–36% of all hyperthyroid patients have indeed a continuous bruit (due to arteriovenous communications within the hyperplastic gland). Compression of neck veins will help differentiate the two.

A carotid bruit is heard higher and lateral to the gland than a thyroid bruit.

A carotid bruit is heard higher and lateral to the gland than a thyroid bruit.

A thyroid bruit can be differentiated from the transmitted murmur of aortic stenosis or aortic sclerosis through a complete cardiac exam, very much like the stridor and hoarseness that often accompany thyromegaly.

A thyroid bruit can be differentiated from the transmitted murmur of aortic stenosis or aortic sclerosis through a complete cardiac exam, very much like the stridor and hoarseness that often accompany thyromegaly.

26 How can one categorize thyroid abnormalities?

By assessing both physical findings and endocrine function (Table 8–1).

| Thyroid Finding | Function | Disease Process |

|---|---|---|

| Diffuse Enlargement | ||

| Diffuse, smooth goiter | Normal | Simple goiter, endemic goiter |

| Multiple nodules | Normal/hyper/hypo | Multinodular goiter |

| Diffuse, bosselated goiter | Hyper | Graves’ disease |

| Firm, small, nontender goiter | Hypo | Chronic thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s) |

| Firm, diffuse tenderness | Hyper/hypo | Subacute thyroiditis |

| Firm, hard, fixed, unmovable gland | Normal | Malignancy |

| Firm, hard, with lymphadenopathy | Normal | Malignancy |

| Focal tenderness | Normal/hypo | Abscess |

| Focal Enlargement | ||

| Toxic with thyroid nodule | Hyper | Functional adenoma (Plummer’s) |

| Transilluminated nodule | Normal | Thyroid cyst |

| Nontoxic with thyroid nodule | Normal | Malignancy |

| Focal tenderness, hyperthyroid | Normal | Hemorrhage in functional adenoma |

E. Goiter

27 What is the normal thyroid size?

“Normal” depends on iodine supply in the local diet. In the not-too-distant past, for example, thyroids became progressively larger as one ascended from the sea to the mountains. In fact, euthyroid goiters were so common in the Swiss and Italian Alps that they became part of the local folklore. For example, one of the most colorful of the Commedia dell’Arte masks was Gioppino, an Alpine mountaineer whose trademark sign was a gigantic goiter (Fig. 8-10). The very word cretin (in reference to endemic and congenital hypothyroidism) also has something to do with mountaineers and goiters. Sapira reminds us that some early Christians ran to the Pyrenees to escape persecution. They escaped successfully, but also acquired hypothyroidism, and the mental slowing associated with it. When traveling to different villages, they were easily recognized and immediately referred to as cretins (Chretien is French for Christian). Huge goiters still occur, but only in mountainous regions (like the Himalayas), where iodinated salt is not routinely instituted.

28 Which physical examination techniques can help establish thyroid size?

30 Why is estimating size clinically important?

Because in patients with suspected or known disease, size can:

31 What is a goiter?

From the Latin guttur (throat), this is a chronic enlargement of the gland (Fig. 8-11). Goiters occur endemically in iodine-deficient areas and sporadically elsewhere. As Sapira reminds us, the Latin for goiter is struma, a term still occasionally used, even though originally it did not indicate an enlarged thyroid, but instead a scrofula (i.e., the widening of the neck that makes the patient resemble a sow [scrofula in Latin]). Although this was mostly due to tuberculous lymphadenopathy, it eventually became linked to the thyroid after the Struma river of Bulgaria, an area of endemic goiter.

33 Are goiters neoplastic?

No. Cancers are usually nodular, even though at times they may be goitrous.

40 So how can physical examination help identify a goiter?

Siminoski recommends the following strategy:

1. Examine the thyroid through inspection and palpation.

2. Categorize it as either normal or goitrous. If a goiter is present, subcategorize it as small (1–2 times normal) or large (>2 times normal).

3. If the goiter is small, consider the possibility of overestimation. Look for prominence in the neck profile and for visibility on frontal view while the neck is extended.

4. Finally, place the patient into one of the following three categories:

41 What may lead to false-positive and false-negative results of goiter detection?

(a) False-positive thyroid enlargement (pseudogoiter)

1. Accentuated prominence of a palpable but in reality normal gland:

Patients with long and curving neckline that makes the thyroid quite prominent in spite of its normal location and size. Such pseudogoiters have been dubbed the Modigliani syndrome, after the Italian artist’s penchant for long and lordotic necks. They are the most common cause of referral for possible goiter.

Patients with long and curving neckline that makes the thyroid quite prominent in spite of its normal location and size. Such pseudogoiters have been dubbed the Modigliani syndrome, after the Italian artist’s penchant for long and lordotic necks. They are the most common cause of referral for possible goiter. Patients whose thyroid is higher than usual in the neck. These account for 10% of all referrals. Important clues are a negative thumb sign and a laryngeal prominence that is more than 10 cm above the suprasternal notch.

Patients whose thyroid is higher than usual in the neck. These account for 10% of all referrals. Important clues are a negative thumb sign and a laryngeal prominence that is more than 10 cm above the suprasternal notch.2. The presence of a fat pad in the anterolateral neck (common in young women and obese patients). In contrast to the thyroid, the fat pad does not rise with swallowing.

3. Anterior neck masses. These can be easily differentiated from goiters by using swallowing. Branchial cleft cysts, cervical lymphadenopathy, and pharyngeal diverticula are all less likely to adhere to laryngeal structures, and thus will not rise with deglutition. Goiters instead will. One important exception is the thyroglossal duct cyst, which not only rises with swallowing, but also does so upon forced tongue protrusion (see Chapter 7, The Neck, questions 10–15).

(b) False-negative thyroid enlargement

1. Inadequate examination skills. The most common reason for a false-negative exam.

2. Short and thick-necked patients, especially if obese, elderly, or with COPD

3. Atypical or ectopic placement of the thyroid. Instead of being cervical, the goiter may be substernal or retroclavicular. Laterally placed lobes, obscured by the SCMs, also may yield false-negative results.

42 What is the overall accuracy of physical examination in detecting a goiter?

Good. Combining data from nine separate studies, sensitivity is 70% and specificity 82%.

44 What is the significance of a negative exam?

Negative inspection, palpation, or a combination thereof does argue against the presence of goiter (LR of 0.4). Yet, it does not exclude it (see question 41). In fact, as many as half of all ultrasonically proven thyromegalies will remain undetected on exam.

50 Are thyroid nodules necessarily neoplastic?

No, only 5% are malignant. The rest are degenerative or adenomatous. Most are euthyroid.

G. Graves’ Disease

52 What is hyperthyroidism?

A constellation of signs and symptoms due to increased blood levels of thyroid hormone.

55 How does hyperthyroidism present?

Hypermetabolism is evidenced by weight loss, preference for colder temperatures, diarrhea, and amenorrhea or scant flow.

Hypermetabolism is evidenced by weight loss, preference for colder temperatures, diarrhea, and amenorrhea or scant flow.

Goiter is present in 70–90% of all hyperthyroid patients—nodular and asymmetric in toxic nodular goiter, symmetric and diffuse in thyroiditis or Graves’ disease. Two thirds of Graves’ and one third of toxic nodular goiters may have a bruit on thyroid exam.

Goiter is present in 70–90% of all hyperthyroid patients—nodular and asymmetric in toxic nodular goiter, symmetric and diffuse in thyroiditis or Graves’ disease. Two thirds of Graves’ and one third of toxic nodular goiters may have a bruit on thyroid exam.

Skin. Some manifestations are specific (pretibial myxedema of Graves’ disease), whereas others relate instead to increased metabolism and thus are nonspecific (warm, moist, velvety skin; fine, silky hair; palmar erythema; hyperpigmentation at pressure points; thin, breakable nails; onycholysis).

Skin. Some manifestations are specific (pretibial myxedema of Graves’ disease), whereas others relate instead to increased metabolism and thus are nonspecific (warm, moist, velvety skin; fine, silky hair; palmar erythema; hyperpigmentation at pressure points; thin, breakable nails; onycholysis).

Changes in the eyes include lid lag, lid retraction (with widened palpebral fissures), and Graves’ ophthalmopathy.

Changes in the eyes include lid lag, lid retraction (with widened palpebral fissures), and Graves’ ophthalmopathy.

Cardiovascular effects include tachycardia, wide pulse pressure, palpitations, and systolic flow murmur.

Cardiovascular effects include tachycardia, wide pulse pressure, palpitations, and systolic flow murmur.

Neurologic symptoms include (1) anxious appearance, restlessness, fidgety behavior; (2) fine tremor on outstretched arms due to increased sympathetic tone; (3) neuromuscular weakness; (4) decreased exercise tolerance in two thirds of cases (as a result of both proximal muscle wasting and the inability of the cardiovascular system to adequately increase output); and (5) hyperreflexia in one fourth of patients.

Neurologic symptoms include (1) anxious appearance, restlessness, fidgety behavior; (2) fine tremor on outstretched arms due to increased sympathetic tone; (3) neuromuscular weakness; (4) decreased exercise tolerance in two thirds of cases (as a result of both proximal muscle wasting and the inability of the cardiovascular system to adequately increase output); and (5) hyperreflexia in one fourth of patients.

57 And so, how does hyperthyroidism present in the elderly?

Mostly with cardiac or neurologic manifestations, often subtle:

Cardiomyopathy or cardiomegaly with high-output failure

Cardiomyopathy or cardiomegaly with high-output failure

Means-Lerman scratch (high-pitched pulmonic sound similar to pericardial friction rub—see Chapter 11, Heart Sounds and Extra Sounds, question 52)

Means-Lerman scratch (high-pitched pulmonic sound similar to pericardial friction rub—see Chapter 11, Heart Sounds and Extra Sounds, question 52)

59 What is the frequency of Graves’ disease?

It depends on gender and age, being higher in women and in the third to fourth decade of life.

62 What does pretibial myxedema look like?

The most common presentation is a localized, nonpitting edema of the shins. The more classic examples are instead well-demarcated, raised, and bilateral pinkish/brownish nodules on the anterior aspects of the shins (Fig. 8-12). These lesions may progress into a plaque or be located elsewhere on the legs, although they rarely involve the feet. Finally, pretibial myxedema may be pruritic or hyperpigmented.

63 How do you distinguish pretibial myxedema from the myxedema of hypo-thyroidism?

Pretibial myxedema is localized, whereas the hypothyroid form is more generalized.

66 What are the ocular manifestations of Graves’?

In addition to the nonspecific sympathetic manifestations of lid lag and lid retraction, Graves’ disease is associated with a unique infiltrative disease of the eyes, characterized by edema and lymphocytic penetration of ocular fat, connective tissue, and extraocular muscles. This may manifest with discomfort, a tearing/gritty sensation in the eyes, and diplopia. Eventually, congestion of multiple layers of the eyeball will cause proptosis of the involved eye (i.e., an abnormal forward protrusion of the eyeball from the orbit—more than 18 mm in extent) and ophthalmoplegia (see Figs. 8-13 and 8-14).

68 How do you detect and assess the degree of proptosis?

The “poor man’s” test is to have the patient bend the head forward while you look down on the orbits and estimate the distance to the corneal surface. This usually allows you to assess whether the distance is indeed greater than normal. For a more accurate measurement, you can use a Hertel exophthalmometer (Fig. 8-15), a hand-held device designed to quantitate the distance between the lateral orbital rim and anterior corneal surface.

70 What are the characteristics of Graves’ congestive ophthalmopathy?

71 What is ophthalmoplegia?

It is the inflammation, infiltration, engorgement, and paralysis of extraocular muscles in patients with Graves’ disease (often referred to as exophthalmic or congestive ophthalmoplegia). It preferentially affects the medial and inferior recti but may result in many extraocular motion defects and impairments, including muscle weakness and amblyopia, impaired upward gaze, impaired convergence, strabismus, visual field defects, and restriction of gaze and visual acuity. Described mostly in the past century by various German and Austrian physicians (plus a couple of Frenchmen, two Britons, a Swiss, and a Russian), these signs carry a plethora of eponyms. Note that lid retraction and lid lag can occur in any hyperthyroid patient, since they are caused by the sympathetic hyperactivity of the Mueller’s muscle (the same responsible for ptosis in Horner’s syndrome). Rosenbach’s sign is also the result of sympathetic hyperactivity. All other signs are instead typical of Graves’ infiltrative ophthalmopathy, occurring in 25–50% of patients (see Table 8-2).

| Sign | Discoverer | Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Dalrymple’s* (lid retraction [i.e., “thyroid stare”]) | John Dalrymple (1803–1852). British ophthalmologist who also played a role in the identification of the Bence-Jones protein. Died at 49 of renal failure. | Abnormal widening of the palpebral fissure. Normally, the margin of the upper lid covers 1 mm of the iris, but in lid retraction the upper eyelid is pulled backward, thus displaying a bit of sclera and giving the patient a typical scared/staring look. May result in corneal exposure with ulceration. |

| Von Graefe’s* (lid lag) | Friedrich Wilhelm Ernst Albrecht von Graefe (1828–1870). German physician and founding father of modern ophthalmology. Died at 42 of tuberculosis. | On downward gaze, the globe moves briskly while the upper lid lags behind, thus disclosing the sclera between the corneal limbus and lid (Fig 8-17). |

| Rosenbach’s* | Ottomar Rosenbach (1851–1907). German physician and controversial promoter of the psychosomatic origin of many diseases. | Fine tremor of the gently closed eyelids. Especially the upper. |

| Möbius’ | Paul Julius Möbius (1853–1907). German neurologist and student of Von Strümpell. | Failure of ocular convergence following close accommodation at 5″. |

| Stellwag’s | Karl Stellwag von Carion (1823–1904). Austrian ophthalmologist. | Infrequent (and incomplete) blinking, plus proptosis. |

| Kocher’s | Emil Theodor Kocher (1841–1917). Swiss surgeon and strong promoter of antisepsis. Nobel laureate for his contribution on thyroid physiology, pathology, and surgery. | On upward gaze, the upper lid retracts briskly while the globe lags behind (counterpart to Von Graefe’s). |

| Joffroy’s | Alexis Joffroy (1844–1908). French neuropsychiatrist and student of Charcot. | Absent wrinkling of the forehead when the eyeballs are rolled upward. |

| Sainton’s | Paul Sainton (1868–1958). French physician and chair at the Hôtel-Dieu Hospital in Paris. | On upward gaze, the frontalis muscle contracts after the upper lid has completely retracted. |

| Jellinek’s | E. H. Jellinek. British neurologist of the 19th century. | Brownish pigmentation of eyelids, especially the upper. |

| Topolansky’s | Russian physician. | Pericorneal congestion in patients with Graves’, with conjunctival edema (chemosis) and hyperemia. |

* Nonspecific signs of hyperthyroidism. All others are typical of Graves’ ophthalmopathy.

72 What is onycholysis?

It is the partial separation of the nail plate from the nail bed at its more distal and lateral attachments (total separation is termed onychomadesis). Onycholysis is an uncommon finding of hyperthyroid states that typically involve the ring finger, wherein the free edge of the nail becomes undulated, upturned, and often so loose as to collect debris beneath it. Onycholysis can also involve all other fingernails. It is due to sympathetic overactivity and thus represents a nonspecific manifestation of hyperthyroidism. When associated with Graves’ disease, it is termed Plummer’s nails (Fig. 8-18). It can also occur with psoriasis, fungal nail infection (usually candidal), trauma, Raynaud’s disease, phototoxic reaction to tetracyclines, and constant wetting of the hands, as in dishwashers (see Chapter 3, The Skin, question 20).

73 Who was Plummer?

Henry Plummer was an American internist. Born in Hamilton, Minnesota, in 1874, he studied at Northwestern University and practiced at the Mayo Clinic from 1901 until his death in 1936. His creativity and innovation led him to redesign the medical records of Mayo and to develop the examination beds that are still commonly used throughout North America. Outside medicine, his interests included literature, music, and especially gardening. Plummer’s name also is linked to a thyroid nodule associated with hyperthyroidism but no ocular manifestations. The condition is sometimes called Plummer-Vinson adenoma in memory of Porter Vinson, a fellow in medicine at the Mayo Clinic and a junior associate of Plummer. This should not be confused with Plummer-Vinson syndrome (sideropenic dysphagia, iron deficiency anemia, dysphagia, esophageal web, and atrophic glossitis), which is not associated with onycholysis, but with the koilonychia of iron deficiency (see Chapter 3, The Skin, question 23).

H. Hypothyroidism

74 What is hypothyroidism?

A constellation of signs and symptoms due to inadequate levels of thyroid hormone.

78 What are the manifestations of hypothyroidism?

| Skin and Soft Tissues | Neurologic Manifestations |

|---|---|

Mostly due to accumulation of water-binding mucopolysaccharides (hence, the term myxedema) Mostly due to accumulation of water-binding mucopolysaccharides (hence, the term myxedema) |

Disinterested, complacent, lethargic Disinterested, complacent, lethargic |

Good muscle strength (but lethargic) Good muscle strength (but lethargic) |

|

Paresthesias Paresthesias |

|

Deafness Deafness |

|

Coarse, dry, scaling, and cool skin (dryness from reduced sebum production, coolness from diminished blood flow) Coarse, dry, scaling, and cool skin (dryness from reduced sebum production, coolness from diminished blood flow) |

Prolonged contraction and relaxation of the Achilles (“hung-up” reflex)—this can separate hypothyroid from euthyroid patients, but when assessed by the naked eye can be absent in three fourths of cases. Prolonged contraction and relaxation of the Achilles (“hung-up” reflex)—this can separate hypothyroid from euthyroid patients, but when assessed by the naked eye can be absent in three fourths of cases. |

Sallow and yellowish color due to accumulation of carotenoids; in contrast to jaundice, also involves palms and soles Sallow and yellowish color due to accumulation of carotenoids; in contrast to jaundice, also involves palms and soles |

Hypothyroid speech (low-pitched, slow, and deep voice that has been compared to a 45 RPM record playing at 33 RPM); it can occur in up to 40% of patients and is due to accumulation of polysaccharides in the vocal cords. Hypothyroid speech (low-pitched, slow, and deep voice that has been compared to a 45 RPM record playing at 33 RPM); it can occur in up to 40% of patients and is due to accumulation of polysaccharides in the vocal cords. |

Periorbital puffiness with facial edema Periorbital puffiness with facial edema |

|

Doughy, nonedematous swelling Doughy, nonedematous swelling |

|

Thick nails Thick nails |

|

Coarse hair that breaks easily Coarse hair that breaks easily |

|

Missing lateral eyebrow (Queen Anne’s sign). Present in one third of hypothyroid patients but also may occur in normal subjects; hence, of limited clinical value. Missing lateral eyebrow (Queen Anne’s sign). Present in one third of hypothyroid patients but also may occur in normal subjects; hence, of limited clinical value. |

|

| Cardiovascular Manifestations | Other Manifestations |

Bradycardia Bradycardia |

Goiter (more specific than sensitive: +LR, 2.8; −LR, 0.6) Goiter (more specific than sensitive: +LR, 2.8; −LR, 0.6) |

Weight gain—not as common as traditionally claimed, and in some studies not any more frequent in hypothyroid than euthyroid patients Weight gain—not as common as traditionally claimed, and in some studies not any more frequent in hypothyroid than euthyroid patients |

|

Constipation Constipation |

|

Menorrhagia Menorrhagia |

79 What is the clinical significance of hypothyroid findings?

They can only suggest the diagnosis, since confirmation of hypothyroidism depends exclusively on a highly sensitive thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) assay. Still, prevalence of symptoms and signs of overt hypothyroidism is remarkably different today from the old reports in the literature. To this end, Zulewski et al. have recently revisited the 1969 Billewicz index by quantifying each of its 14 signs and symptoms (Table 8–4) as +1 if present and 0 if absent. Using as gold standard modern thyroid function tests (absent in Billewicz’s time) they defined as hypothyroid patients with a cumulative score >5; as euthyroid those with score ≤2; and as intermediate (or borderline hypothyroid) those with scores 2–5. By doing so, they were able to identify 62% of overt hypothyroid and 24% of subclinical hypothyroid patients, as compared to 42% and 6%, respectively, when using Billewicz’s definition. As for hyperthyroidism, clinical scores of hypothyroidism may perform less well in the elderly. Overall, findings more strongly suggestive of hypothyroidism are: bradycardia (+LR = 3.88), abnormal ankle reflex (+LR = 3.41), and coarse skin (+LR = 2.3). Cool and dry skin also has high likelihood ratio. Still, no single finding, when absent, can effectively rule out hypothyroidism (−LR = 0.42–1.0). Even the combination of signs with the highest likelihood ratios (coarse skin, bradycardia, and delayed ankle reflex) is only modestly accurate (+LR = 3.75; −LR = 0.48).

Table 8-4 Frequency of Hypothyroid Signs and Symptoms in Patients and Controls

| Patients (%) | Controls (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sign/Symptom | (n = 50) | (n = 80) |

| Ankle reflex | 77 | 6.5 |

| Dry skin | 76 | 36.2 |

| Cold intolerance | 64 | 36 |

| Coarse skin | 60 | 18.3 |

| Puffiness | 60 | 3.7 |

| Pulse rate | 58 | 57.5 |

| Sweating | 54 | 13.8 |

| Weight | 54 | 22.5 |

| Paresthesia | 52 | 17.5 |

| Cold skin | 50 | 20 |

| Constipation | 48 | 15 |

| Movements | 36 | 1.3 |

| Hoarseness | 34 | 12.5 |

| Hearing | 22 | 2.5 |

(Data from Zulewski H, Muller B, Exer P, et al: Estimation of tissue hypothyroidism by a new clinical score: Evaluation of patients with various grades of hypothyroidism and controls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:771–776, 1997.)

1 Bahn RS, Heufelder AE. Pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1468-1475.

2 Bartley GB. The differential diagnosis and classification of eyelid retraction. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:168-176.

3 Bartley GB, Fatourechi V, Kadrmas EF, et al. Clinical features of Graves’ ophthalmopathy in an incidence cohort. Ant J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:284-290.

4 Basaria R. Pemberton’s sign. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1338.

5 Berghout A, Wiersinga WM, Smits NJ, et al. Determinants of thyroid volume as measured by ultrasonography in healthy adults in a non-iodine deficient area. Clin Endocrinol. 1987;26:273-280.

6 Berghout A, Wiersinga WM, Smits NJ, et al. The value of thyroid volume measured by ultrasonography in the diagnosis of goiter. Clin Endocrinol. 1988;28:409-414.

7 Bicknell PG. Mild hypothyroidism and its effects on the larynx. J Laryrngol Otol. 1973;87:123-127.

8 Billewicz WZ, Chapman RS, Crooks J, et al. Statistical methods applied to the diagnosis of hypothyroidism. Q J Med. 1969;38:255-265.

9 Blum M, Biller BJ, Bergman DA. The thyroid cork. Obstruction of the thoracic inlet due to retroclavicular goiter. JAMA. 1974;227:189-191.

10 Brander A, Viikinkoski P, Tuuhea J, et al. Clinical versus ultrasound examination of the thyroid gland in common clinical practice. J Clin Ultrasound. 1992;20:37-42.