18 The thigh and knee

The knee depends for its stability upon its four main ligaments and upon the quadriceps muscle. The importance of the quadriceps cannot be overemphasised. So efficiently can a powerful quadriceps control the knee that it can maintain stability despite considerable laxity of the ligaments. In many injuries and diseases of the knee the quadriceps wastes strikingly, and to some extent the condition of the muscle is an index of the state of the knee: if it is wasted it is probable that there is a significant abnormality within the joint.

The knee is, in fact, a region where nearly every kind of orthopaedic disorder may be represented.

SPECIAL POINTS IN THE INVESTIGATION OF THIGH AND KNEE COMPLAINTS

History

The history is of particular importance in the diagnosis of disorders of the knee. In a case of torn meniscus, for instance, the history is often the most important factor in the clinical diagnosis. When there has been a previous injury to the knee, the exact sequence of events at the time of the injury and afterwards must be ascertained. Enquiry is made into the mechanism of the injury; what the patient was doing at the time; whether he was able to carry on afterwards. Was he able to finish the game? If not, was he carried from the field or was he able to walk? How soon after the injury did the knee swell? Was he able to straighten the knee fully? If not, how did he eventually get it straight? Was he able to bend it? These and many other details must be elicited by careful questioning because they are so important in building up a picture of what exactly happened to the knee. Caution is necessary in accepting the patient’s story of ‘locking’ at its face value. Many patients speak of ‘locking’ when the knee simply feels stiff and painful, or when it causes momentary jabs of pain on movement. Locking from a torn meniscus means simply that the knee cannot be straightened fully; it can usually be flexed freely. In locking from a loose body within the joint the knee may be jammed so that it will neither flex nor extend, but this is rather uncommon and the knee usually unlocks itself after an interval, or can be freed by judicious manoeuvring.

Steps in clinical examination

A suggested routine for clinical examination of the thigh and knee is summarised in Table 18.1.

Table 18.1 Routine clinical examination in suspected disorders of the thigh and knee

| 1. LOCAL EXAMINATION OF THE THIGH AND KNEE | |

| Inspection | Power (tested against resistance of bone contours and alignment examiner) |

| Soft-tissue contours | Flexion |

| Colour and texture of skin | Extension |

| Scars or sinuses | |

| Palpation | Stability |

| Skin temperature | Medial ligament |

| Bone contours | Lateral ligament |

| Soft-tissue contours | Anterior cruciate ligament: anterior draw test; Lachman test; pivot shift test |

| Local tenderness | Posterior cruciate ligament |

| Measurements of thigh girth | Rotation tests (McMurray) |

| Comparative measurements at precisely the same level in each limb give an indication of the relative bulk of the thigh muscles, and in particular of the quadriceps | (Of value mainly when a torn meniscus is suspected) |

| Movements (active and passive, against normal knee for comparison) | Stance and gait |

| Flexion | |

| Extension | |

| ? Pain on movement | |

| ? Crepitation on movement | |

| 2. EXAMINATION OF POTENTIAL EXTRINSIC SOURCES OF THIGH OR KNEE SYMPTOMS | |

Determining the cause of a diffuse joint swelling

A diffuse swelling of the knee can arise only from three fundamental causes:

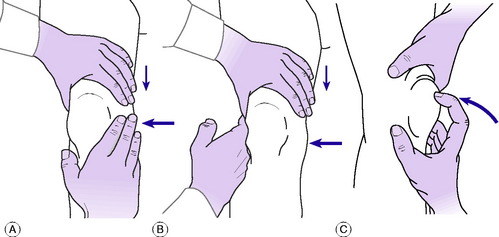

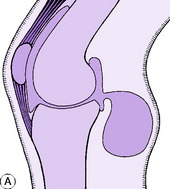

Fluid within the joint. A fluid effusion is best detected by the fluctuation test. The palm of one hand is placed upon the thigh immediately above the patella – that is, over the suprapatellar pouch. The other hand is placed over the front of the joint, with the thumb and index finger just beyond the margins of the patella (Fig. 18.1A). Pressure of the upper hand upon the suprapatellar pouch drives fluid from the pouch into the main joint cavity, where it bulges the capsule at each side of the patella and imparts an easily detectable hydraulic impulse to the finger and thumb of the lower hand (Fig. 18.1B). Conversely, by pressure of this finger and thumb the fluid can be driven back into the suprapatellar pouch, the hydraulic impulse being clearly received by the upper hand. In this way an unmistakable sense of fluctuation can be elicited between the two hands. With practice it is easy to detect even a small effusion in this way. The ‘patellar tap’ test (Fig. 18.1C), in which the patella is tapped backwards sharply so that it strikes the femur and rebounds, though still used, is less reliable. The test is negative in the presence of fluid in two circumstances: first, when there is insufficient fluid to raise the patella away from the femur; and secondly, when there is a tense effusion. If used at all, the ‘patellar tap’ test should be used only as a supplementary method.

Thickening of synovial membrane. A thickened synovial membrane is always a prominent feature of chronic inflammatory arthritis. The thickening is often most obvious above the patella, where the reduplicated membrane forms the suprapatellar pouch. It has a characteristic boggy feel on palpation, rather as if a sheet of warm sponge-rubber had been placed between the skin and the underlying bone. It is worth emphasising that since it is highly vascular, a thickened synovial membrane is always associated with increased warmth of the overlying skin.

Tests for stability

The integrity of each of the four major ligaments is tested in turn.

Testing the medial and lateral ligaments. For this test the joint must be in a position just short of full extension, so that the posterior part of the joint capsule is relaxed: with the knee fully extended even marked laxity of the collateral ligaments can be masked by the intact posterior capsule, held taut. It must be remembered, however, that with the knee slightly flexed the medial and lateral ligaments are normally somewhat slack and allow a little side-to-side wobble. Technique: Support the limb by a hand gripping the ankle region and by the other hand behind the knee, flexing it slightly. Instruct the patient to relax the muscles. Using the more proximal hand as a fulcrum on the appropriate side of the knee, apply first an abduction force to test the medial ligament (Fig. 18.2A) and then an adduction force to test the lateral ligament. If the ligament is torn, the joint will open out more than in the normal knee when stress is applied.

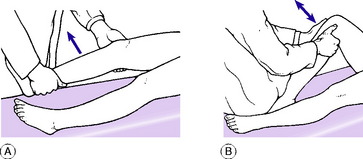

Testing the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments. The anterior cruciate ligament prevents anterior glide of the tibia on the femur; the posterior cruciate ligament prevents posterior glide. First the ligaments are tested with the knee flexed 90 °. Technique: The patient’s knee being flexed to a right angle and the foot placed firmly on the couch, sit lightly on the foot to prevent it from sliding (Fig. 18.2B). With the interlocked fingers of the two hands form a sling behind the upper end of the tibia, and clasp the sides of the leg between the thenar eminences. Place the tips of the thumbs one upon each femoral condyle. Ensure that the patient has relaxed the thigh muscles. Alternately pull and push the upper end of the tibia to determine the amount of antero-posterior movement. Normally there is an antero-posterior glide of up to half a centimetre; but since the normal is variable it is wise to use the patient’s sound limb for comparison. Excessive glide in one or other direction indicates damage to the corresponding cruciate ligament.

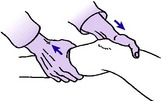

In a second test the ligaments are examined with the knee flexed only 15 ° or 20 ° (Lachman test). One hand supports the thigh just above the knee, gripping the femoral condyles, while the other hand grasps the upper end of the tibia (Fig. 18.3). While the patient relaxes the muscles the extent of any anterior or posterior glide of the tibial condyles upon the femur is determined by push-and-pull movements of the tibia.

Lateral pivot shift. The test for lateral pivot shift is supplementary to the tests described above for deficiency of the anterior cruciate ligament: it may be positive when the foregoing test is equivocal. The test depends on the fact that when the anterior cruciate ligament and the lateral ligament are deficient or lax the pivot between the lateral condyle of the femur and that of the tibia may be unstable. In that event the lateral tibial condylar surface may be displaced forwards in relation to the femoral condyle when the tibia is rotated medially with the knee straight. When the knee is then flexed the subluxation is spontaneously reduced with a visible or palpable ‘jerk’. The test is thus an indication of antero-lateral instability.

Technique. The leg on the affected side is lifted by the examiner’s corresponding hand (the right foot is lifted by the right hand; the left leg by the left hand) so that the knee drops into full extension with the muscles relaxed. The limb is supported under the arm, and with the other hand the examiner then presses against the outer aspect of the limb just below the knee, imparting a valgus strain (Fig. 18.4). At the same time the tibia is rotated medially upon the femur. The knee is now flexed slowly from the straight position. If the test is positive the lateral tibial condyle becomes spontaneously relocated on the femoral condyle when the knee reaches 30 ° or 35 ° of flexion. The relocation is evidenced by a visible or palpable jerk (hence the term ‘jerk test’ sometimes used for the manoeuvre).

Arthroscopy

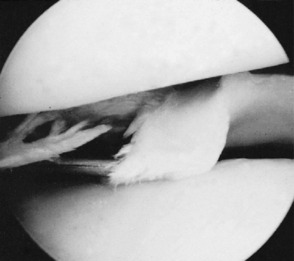

Arthroscopy can be a useful adjunct to clinical and radiographic examination in the diagnosis of knee complaints (Fig. 18.5). Its use for diagnostic purposes has been largely replaced by MRI, but it is a well’established method of treating a number of intra-articular disorders by minimally invasive operation.

Arthroscopy is usually carried out with the patient anaesthetised, the joint cavity is filled with saline through a hollow needle, and a cannula and telescope are entered at the appropriate site – usually antero-laterally or antero-medially, depending upon whether the surgeon is concerned to inspect mainly the medial or the lateral compartment. By correctly manoeuvring and rotating the arthroscope, and if necessary by the use of alternative sites of entry, almost the whole extent of the interior of the joint can be brought into view with the possible exception of the postero-lateral recess. The information gained can be enhanced by probing the menisci and other intra-articular structures with an instrument introduced at a site away from the arthroscope.

DISORDERS OF THE THIGH

ACUTE OSTEOMYELITIS (General description of acute osteomyelitis, p. 85)

The femur is one of the bones most commonly affected by pyogenic osteomyelitis. The infection is carried to the femur either through the blood stream (haematogenous osteomyelitis), when it usually affects the lower metaphysis; or it is introduced through an external wound, especially in cases of compound fracture. The clinical features and treatment are the same as those of osteomyelitis elsewhere (p. 89).

CHRONIC OSTEOMYELITIS (General description of chronic osteomyelitis, p. 90)

Chronic pyogenic osteomyelitis is nearly always a sequel to acute infection that has been neglected or has responded poorly to treatment. As with the acute disease, the lower end of the femur is affected more often than the upper; but in many cases the infection spreads to involve a large part of the femoral shaft. Clinical features and treatment are like those of chronic osteomyelitis elsewhere (p. 91).

BONE TUMOURS IN THE THIGH

The femur is one of the commonest sites of the important bone tumours.

Benign tumours (General description of benign bone tumours, p. 106)

Giant-cell tumour (osteoclastoma)

The lower end of the femur is a particularly frequent site for this uncommon tumour. The upper end of the femur is affected much less often. The tumour usually arises in young adults. It begins in what was the metaphysial region, but since the epiphysis is fused there is no obstacle to its spread into the articular end of the bone (see Fig. 8.10A&B). The bone is gradually expanded, the cortex becoming very thin and pathological fracture may sometimes occur.

Malignant tumours (General description of malignant bone tumours, p. 112)

Osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma)

This is usually a tumour of childhood or early adult life: when it occurs in patients beyond middle age it is usually a complication of Paget’s disease. Typically it arises in the metaphysis of a long bone, and the lower metaphysis of the femur is the favourite site. The tumour is highly malignant, with a mortality still in the region of 40% or more despite recent advances in treatment. Treatment is discussed on page 117.

Ewing’s tumour

This also occurs mainly in children or adolescents. Unlike most bone tumours, it usually affects the shaft of the bone, which it expands in a fusiform manner. Over it, layer upon layer of new bone is laid down, giving a typical ‘onion-peel’ appearance as seen in the radiographs. Although the tumour responds dramatically to chemotherapy, usually in combination with radiotherapy or surgical excision, the prognosis remains poor, with a mortality in the region of 50 per cent from blood-borne metastases. Treatment is discussed on page 121.

Metastatic (secondary) tumours

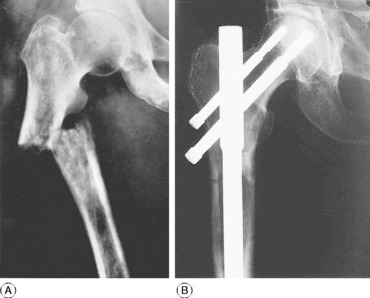

The femur is commonly invaded by metastatic tumours, especially in its proximal half (Fig. 18.6).

Pathology. The tumours that metastasise most readily to bone are carcinomas of the lung, breast, prostate, kidney, and thyroid. The bone structure is usually destroyed by the tumour and pathological fracture is common (Fig. 18.6A).

Treatment. The principles of treatment of metastatic tumours in bone were described on page 126. Most pathological fractures of the femur lend themselves well to internal fixation with a long modified intramedullary nail, though sometimes this requires the addition of acrylic bone cement to achieve stability (Fig. 18.6B). Where massive bone destruction has occurred in the proximal or distal femur, it may be necessary to replace this with a custom prosthesis. This facilitates nursing and greatly increases the quality of life because external splintage can be dispensed with and the patient mobilised.

ARTICULAR DISORDERS OF THE KNEE

PYOGENIC ARTHRITIS OF THE KNEE (General description of pyogenic arthritis, p. 96)

Treatment. Appropriate antibiotic therapy must be started immediately (see p. 98). Local treatment: The joint is rested in a plaster splint in a position of 20 ° of flexion. The purulent effusion is removed daily by aspiration so long as it re-forms or by arthrotomy. Rest is continued until the infection has been overcome; thereafter active movements are encouraged.

TUBERCULOUS ARTHRITIS OF THE KNEE (General description of tuberculous arthritis, p. 98)

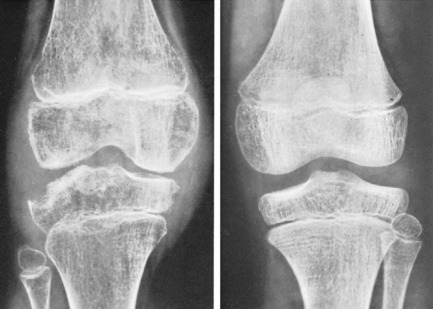

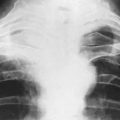

Radiographic features. The earliest change is diffuse rarefaction throughout the area of the knee (Fig. 18.7). Later, unless the disease is arrested, there is narrowing of the cartilage space and erosion of the underlying bone.

Treatment. Constitutional treatment, by antituberculous drugs, is the same as that for other tuberculous joints (p. 102). Local treatment is at first by rest in a splint or plaster, generally for two to three months in the first instance, depending on severity and progress. Subsequent management depends upon the response to treatment and the state of the joint at the end of this period of immobilisation. If the articular cartilage and bone are still intact, if the general health is good and the local signs have subsided, and if the erythrocyte sedimentation rate has steadily improved, it is likely that the disease has been aborted. In that event active joint movements are encouraged and walking is gradually resumed.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS OF THE KNEE (General description of rheumatoid arthritis, p. 134)

The knees are among the joints most frequently affected by rheumatoid arthritis, and they often suffer severe permanent disability. Both knees are often affected simultaneously with several other joints.

Imaging. Radiographs do not show any abnormality at first. Later there is diffuse rarefaction of the bone in the area of the joint. In long-established cases destruction of articular cartilage leads to narrowing of the joint space (Fig. 18.8), and there may be clear-cut erosions of bone, characteristically at the articular margins. Radioisotope bone scanning shows increased uptake of isotope in the region of the joint.

Treatment. In the active stage the treatment is that for rheumatoid arthritis in general and requires coordinated care by a multi-disciplinary team (p. 137). Local treatment for the knees depends upon the severity of the inflammatory reaction. If it is severe, rest in bed or even temporary immobilisation with moulded plaster or polythene splints is advisable. When it is moderate or slight, activity within the limits of pain is encouraged. Physical treatment is worth a trial. The most effective methods are exercises to preserve muscle power and joint movement, and local heat in the form of short-wave diathermy. Injections of hydrocortisone into the joint have sometimes given relief, but repeated injections are inadvisable because they may accelerate the destructive process.

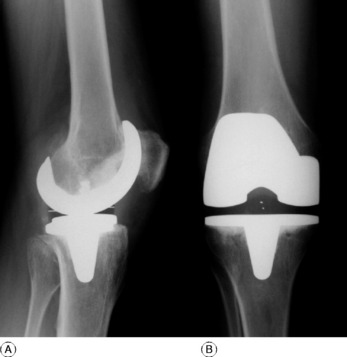

Replacement arthroplasty. Replacement arthroplasty of the knee now gives as good results as have been achieved at the hip. Excellent and durable results are now being achieved in over 90 per cent of patients after ten years. In a favourable case pain is well relieved and good function is restored, with perhaps 90 ° or more of flexion movement. Replacement arthroplasty of the knee is particularly valuable for patients with severe disorganisation of the joint, and especially for elderly patients with involvement of several other joints.

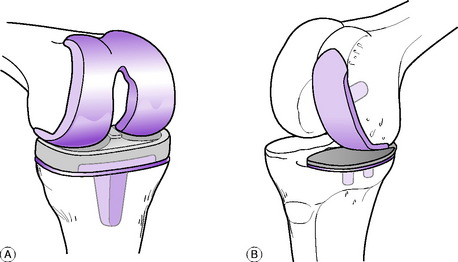

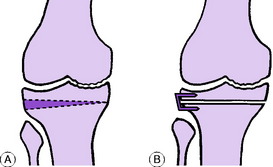

The present trend is to provide gliding articular surfaces rather than a pivoted hinge. Thus the femoral condyles may be replaced by a metal prosthesis cemented in place, and the tibial condyles by a matching polyethylene prosthesis, usually with a metal backing (total condylar replacement, Fig. 18.9A). When badly damaged, the patella may also be resurfaced with a matching polyethylene bearing. In unicompartmental arthritis, the medial or the lateral femoral condyle may be replaced alone (Fig. 18.9B). However, this is only suitable for osteoarthritis and in most cases of inflammatory arthritis, bicondylar replacement is preferred (Fig. 18.10). Many different types of total knee prosthesis are now available, including designs that incorporate artificial menisci, but medium’term results show no obvious advantages over the excellent results obtained with the original condylar replacements.

OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE KNEE (General description of osteoarthritis, p. 140)

The knee is affected by osteoarthritis more often than any other joint. The condition is particularly common in elderly, obese women.

Clinical features. The patient is commonly an elderly, heavy woman, in whom both knees may be affected. In another group, mostly in men, there is a history of previous mechanical derangement from a sports injury. There is slowly increasing aching pain in the joint, worse after unusual activity, and ‘grating’ may be felt or heard on movement. The symptoms are often exacerbated by a slight strain or twist. There is usually evidence of one of the predisposing factors mentioned above.

Radiographic features. Narrowing of the cartilage space, which is the first sign of osteoarthritis in most joints, is often not discernible until a later stage in the case of the knee. An earlier sign in many cases is sharpening or ‘spiking’ of the joint margins, especially of the patella (Fig. 18.11) and tibia. Later, narrowing of the cartilage space is obvious, osteophytes form at the joint margins, and the subchondral bone may become sclerotic (Fig. 18.12). Opacities that appear to be loose bodies are often seen; most are not in fact loose but are attached to the synovial membrane.

Operative treatment. In advanced arthritis, with severe persistent pain, especially when associated with deformity and stiffness, operation may be advisable. Its nature will depend upon the circumstances of each case. The following are the operations most used:

Upper tibial osteotomy. Tibial osteotomy aims to relieve pain and to correct deformity. It is especially valuable when wear of articular cartilage and bone has affected one half of the tibio-femoral joint more than the other. Commonly the medial half of the joint is markedly narrowed whereas the lateral compartment remains relatively healthy. There will be obvious bow-leg deformity and pain is likely to be prominent in the degenerate medial compartment, which is forced by the mal-alignment to take most of the weight (Fig. 18.13A). Correction of the mal-alignment by removal of a wedge of bone based laterally (Fig. 18.13B) transfers the weight-bearing thrust towards the more healthy lateral compartment and is often effective in relieving pain. Likewise if the lateral compartment is worn more than the medial, with consequent genu valgum, a medially based wedge may be excised. The osteotomy is done about 1.5 cm below the upper articular surface of the tibia, and to permit early walking the fragments are usually fixed together at operation by metal staples (Fig. 18.13B).

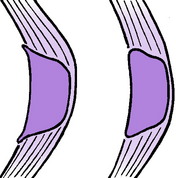

Arthroplasty (see Fig. 18.10). This has now become established as the surgical treatment of choice for advanced osteoarthritis of the knee. It will correct deformity, relieve pain, and restore mobility in over 90% of patients, with results extending out for 10–15 years. Methods of replacement arthroplasty were outlined for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis on page 392. Most commonly the same techniques of total replacement arthroplasty of both the tibio-femoral and patello-femoral joints are used in osteoarthritis. However, unicompartmental tibio-femoral arthroplasty is now being increasingly used as an alternative to upper tibial osteotomy in younger active patients to restore more movement when the arthritis is at an early stage and confined to one compartment. A curved metal prosthetic replacement is fixed to the affected femoral condyle and articulates with a polyethylene tibial component, either directly, or through a gliding polyethylene meniscal bearing to provide more physiological movement (Fig. 18.14). The results in appropriately selected cases are as good as those from total joint replacement and still allow later revision to the full procedure if required at a later stage.

HAEMOPHILIC ARTHRITIS OF THE KNEE (General description of haemophilic arthritis, p. 145)

Investigations. The clotting time of the blood is increased.

Diagnosis. Because of the synovial thickening, increased warmth of the skin and restriction of knee movements, haemophilic arthritis is easily mistaken for chronic inflammatory arthritis. A history of previous bleeding incidents and the increased clotting time of the blood are the important distinguishing features. Biopsy should be avoided because it may cause further bleeding. A history of haemophilia in other male family members also provides a clue.

The chronic degenerative arthritis that results from multiple repeated haemarthroses may have to be controlled by the permanent use of a polythene knee splint. Operative treatment to reduce this risk – such as arthroscopic synovectomy – is practicable, but only under the cover of adequate doses of antihaemophilic factor. When joint contractures or deformities develop, they may require tendon release or lengthening, or even corrective osteotomies. Advanced haemophiliac arthropathy (see Fig. 9.7, p. 147) may necessitate replacement arthroplasty of the joint to restore mobility. This is now possible under factor VIII cover, which needs to be continued for 2–3 weeks after surgery. The majority of patients get good results, but there is a greater risk of complications, particularly infection as many patients have acquired HIV from contaminated blood transfusions.

ANTERIOR KNEE PAIN (Including chondromalacia of the patella)

Anterior knee pain is a generic term that almost certainly includes more than a single clinical entity. The non-specific nature of the label implies, correctly, that the pathogenesis of the pain is not always well understood. The clinical syndrome characteristically occurs in adolescents, especially girls, though it also affects athletes, particularly runners. The description that follows relates to one well-recognised type of lesion, namely chondromalacia of the patella. Similar symptoms may occur in the absence of demonstrable patellar changes, and their causation is often conjectural. Chondromalacia may represent part of a spectrum of conditions associated with patellar instability or malalignment. These also include the more severe disorders of recurrent or habitual dislocation (see p. 409).

TEARS OF THE MENISCI

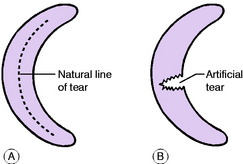

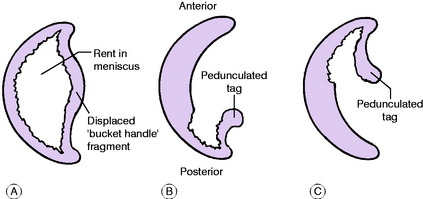

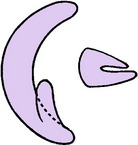

Pathology. In patients of athletic age there are three types of meniscus tear, but all begin as a longitudinal split (Fig. 18.15A) which must be distinguished from the iatrogenic transverse tear resulting from operative trauma (Fig. 18.15B). If the split extends throughout the length of the meniscus it becomes a bucket-handle tear, in which the fragments remain attached at both ends (Fig. 18.16A). This is much the commonest type. The ‘bucket handle’ (that is, the central fragment) is displaced towards the middle of the joint, so that the condyle of the femur rolls upon the tibia through the rent in the meniscus (Fig. 18.16A). Since the femoral condyle is so shaped that it requires most space when the knee is straight, the chief effect of a displaced ‘bucket-handle’ fragment is that it limits full extension (= ‘locking’).

If the initial longitudinal tear emerges at the concave border of the meniscus a pedunculated tag is formed. In posterior horn tear the fragment remains attached at its posterior horn (Fig. 18.16B); in anterior horn tear it remains attached at its anterior horn (Fig. 18.16C). The peripheral part of the meniscus is vascular and tears in the peripheral third can sometimes be sutured as they have some capacity for healing. The inner part is avascular and does not heal, tears in the inner third therefore need to be excised.

As the inner parts of the meniscus are almost avascular, when they are torn there is not an effusion of blood into the joint. Instead there is an effusion of clear synovial fluid, secreted in response to the injury.

In the ‘silent’ phase between attacks there are often no signs other than wasting of the quadriceps.

Imaging. Plain radiographs are usually normal, whether the tear be of the medial or of the lateral meniscus, but in untreated cases of long duration signs of early degenerative arthritis may be noted in the affected compartment. Arthrography will often demonstrate meniscal tears, but it is now seldom undertaken because MRI is even more reliable in demonstrating the various types of tear and is non-invasive (Fig. 18.17).

Arthroscopy. On arthroscopic examination a meniscal tear can be seen whatever its site, except sometimes at the posterior end of the lateral meniscus (Fig. 18.18).

Treatment. Once the diagnosis is established the standard treatment is to excise either the whole meniscus or, more appropriately in most cases, the displaced ‘bucket-handle’ fragment alone. This operation is usually best carried out by the arthroscopic technique without formal opening of the joint – though of course the joint may be opened by incision if difficulty arises during the course of arthroscopic surgery. In selected cases of peripheral tear, repair by suture is sometimes undertaken using a semi-closed arthroscopic technique.

HORIZONTAL TEAR OF DEGENERATE MEDIAL MENISCUS

The meniscal tears described above are uncommon in patients over the age of 50, when the menisci begin to show degenerative changes. But a degenerate meniscus is liable to suffer a different type of lesion. The medial meniscus in particular may split horizontally at a point often near the middle of its convexity (Fig. 18.19). Such a split is usually of small dimensions, and since there is no separation of the fragments natural healing can occur.

CYSTS OF THE MENISCI

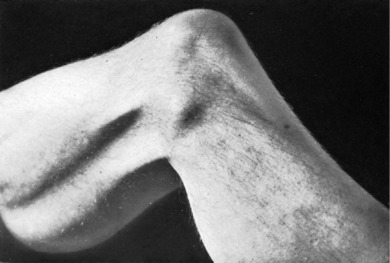

Clinical features. The lateral meniscus is affected much more often than the medial. There is visible swelling, most obvious when the knee is held slightly flexed, at the level of the joint and usually anterior to the lateral (or medial) ligament (Fig. 18.20). The swelling tends to be painful at night and it is usually tender on firm pressure. The swelling is so tense that fluctuation can seldom be elicited – indeed it is sometimes mistaken for bone.

Imaging. Radiographs may show an indentation of the side of the tibial condyle where the cyst has been in contact with it. MRI scanning will confirm the origin of the cyst from the meniscus (Fig. 18.21) and exclude more serious soft’tissue tumours.

Treatment. If the disability justifies operation the cyst should be excised together with the meniscus from which it arises. Very occasionally, it may be practicable to excise the cyst arthroscopically while leaving the meniscus intact.

OSTEOCHONDRITIS DISSECANS OF THE KNEE (General description of osteochondritis dissecans, p. 153)

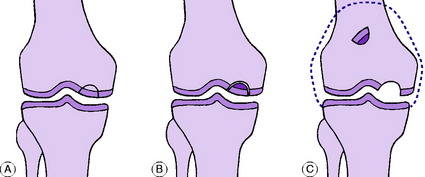

Pathology. The lesion nearly always affects the articular surface of the medial condyle of the femur (Fig. 18.22). The size of the affected segment varies – it is often about 2 cm in diameter. Within the area of the lesion the subchondral bone is avascular and the overlying cartilage softens. A clear line of demarcation forms between the avascular segment and the surrounding normal bone and cartilage (Fig. 18.22A). After many months the fragment separates as a loose body (sometimes two or three), leaving a shallow cavity in the articular surface which is ultimately filled with fibrocartilage (Fig. 18.22B&C). The damage to the joint surface predisposes to the later development of osteoarthritis, especially when the fragment is large.

Imaging. Radiographs show a clear-cut defect of the bone at the articular surface of the medial femoral condyle (Fig. 18.23). At first the cavity is occupied by the separating fragment of bone; but later the cavity may be empty, and a loose body will then be seen elsewhere in the joint. The lesion is shown best in tangential postero-anterior projections with the knee semiflexed (Fig. 18.23B). The advent of MRI has provided more valuable information on the state of the overlying articular cartilage and whether this is healing or liable to separate (Fig. 18.24).

Treatment. In the developing stage treatment should be expectant: the knee is supported with a crepe bandage and strenuous activities are curtailed. Sometimes in these early cases the lesion will heal spontaneously, especially in young adolescents, and can be monitored by repeat MRI.

LOOSE BODIES IN THE KNEE

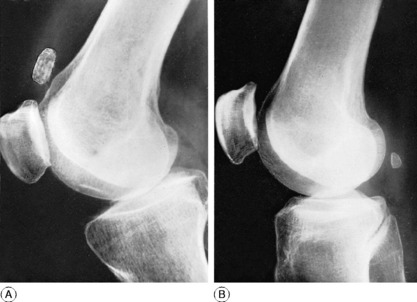

Pathology. Osteochondritis dissecans was described on page 153. A loose body may be formed by spontaneous separation of a fragment of bone and cartilage from the articular surface of the medial femoral condyle. The loose body lies free in the joint, and a shallow cavity remains in the condyle.

Osteoarthritis was described on page 393. Some of the loose bodies that may be found in osteoarthritis are probably formed by detachment of marginal osteophytes. Most separated osteophytes, however, retain a synovial attachment and do not cause trouble: although they appear loose in radiographs they should not be regarded as such unless symptoms of locking indicate that they are moving freely within the joint. True loose bodies may possibly form from flakes of articular cartilage shed into the joint that gradually enlarge, nourished by synovial fluid.

Synovial chondromatosis (osteochondromatosis) is a rare disease of the synovial membrane (p. 152). It is characterised by the formation of numerous small villous processes, which become pedunculated. Later their bulbous extremities become cartilaginous and they are detached to lie free in the joint. Finally, some or all of the numerous loose bodies become calcified.

Radiographic features. With few exceptions, loose bodies are shown radiographically. They often lie in the suprapatellar pouch (Fig. 18.25A). Care should be taken not to mistake the fabella (a seasmoid bone in the lateral head of the gastrocnemius) (Fig. 18.25B) for a loose body. The position of the fabella is constant: it lies slightly above the level of the joint well behind the femur and towards the lateral side, and it is always oval in shape with its long axis vertical.

RECURRENT DISLOCATION OF THE PATELLA

The patello-femoral joint is one of the three joints that are most liable to recurrent displacement, the others being the shoulder and the ankle. In the case of the patello-femoral joint, unlike the other two, the instability is often caused by congenital factors rather than by an initial violent injury.

This last factor is seldom an important one.

Clinical features. Recurrent dislocation of the patella is more common in girls than in boys. Often both knees are affected. Trouble usually begins during adolescence. Dislocation occurs while the patient is engaged in some activity that entails flexing the knees – not necessarily a violent exertion. Suddenly, while the knee is flexed or semiflexed, there is severe pain in the front of the knee, and the patient is unable to straighten it. Often the displacement of the patella is recognised and reduced on the spot, either by the patient herself or by an onlooker.

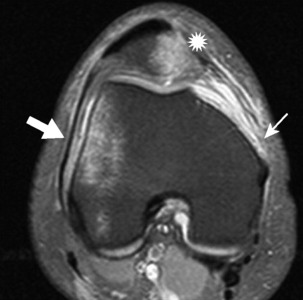

MRI scans may be more informative and may demonstrate damage to the articular surface of the patella and any defects or tears in the medial soft’tissue structures (Fig. 18.26).

Course. Dislocation of the patella does not always become recurrent: some patients have no further trouble after an initial dislocation. But in most cases dislocations recur with ever-increasing ease and frequency, so that the patient may become seriously handicapped. Oft-repeated dislocations predispose to the later development of osteoarthritis.

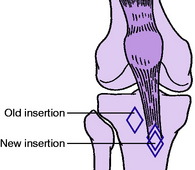

If the dislocations recur with such frequency that the patient is seriously disabled, operation should be advised. The method often recommended is to detach the bony insertion of the patellar tendon and transpose it to a new bed in the tibia, medial and distal to the original insertion (Fig. 18.27). In this way the patella is drawn lower into the deeper part of the intercondylar groove of the femur, and the line of pull of the quadriceps mechanism is transferred more to the medial side. This operation is often criticised on the grounds that it may be followed, after an interval of many years, by the development of degenerative arthritis. But such arthritis is an in-built complication of recurrent dislocation of the patella and cannot be ascribed solely to the operation. Other operations include release of tight soft tissues at the lateral side of the joint, reefing of the quadriceps expansion, and repair of the soft tissues on the medial side.

EXTRA-ARTICULAR DISORDERS IN THE REGION OF THE KNEE

GENU VARUM AND GENU VALGUM

Genu varum (bow leg) and genu valgum (knock knee) occur commonly in childhood. In the vast majority of instances there is no underlying disease, and the deformity need not cause anxiety because it is gradually corrected spontaneously as the child grows.

Benign genu varum of toddlers

The knee and leg are bowed outwards (Fig. 18.28A). A mild degree of this deformity is so common as to be almost normal in children aged 1 to 3 years. It does not require treatment unless it persists into later childhood. Care should be taken to exclude the possibility of rickets or other underlying bone disease.

Benign genu valgum of childhood

The knee is angled inwards, the tibia being abducted in relation to the femur. With the knees straight, the medial malleoli cannot be brought into contact (Fig. 18.28B). The ‘knock-knee’ deformity is common in children aged 3 to 5 years. In the absence of underlying bone disease it usually corrects itself spontaneously in the course of years.

Treatment. In early childhood treatment is unnecessary, but it is common practice (albeit of doubtful relevance) to fit a wedge, base medially and 3–5 millimetres deep, to the heel of the shoe. In theory this tends to shift the line of weight-bearing medially, which in turn favours correction of the deformity (see Fig. 19.20).

Severe genu valgum persisting after the age of 10 requires active treatment. In growing children two methods of correction are available. One is to retard the growth at the medial side of the epiphysial cartilage of the femur or tibia by bridging the epiphysis to the diaphysis with metal staples (epiphysiodesis). The other and more certain method is by supracondylar osteotomy of the femur – or of the upper end of the tibia if the fault lies there – with excision of a suitable wedge from the medial side. After the cessation of epiphysial growth genu valgum can be corrected only by osteotomy.

RUPTURE OF THE QUADRICEPS APPARATUS

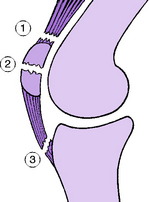

The quadriceps muscle gains insertion into the tibia through the medium of the patella (enclosed within the quadriceps expansion) and the patellar tendon. Complete rupture may occur at three points (Fig. 18.29):

Avulsion from patella

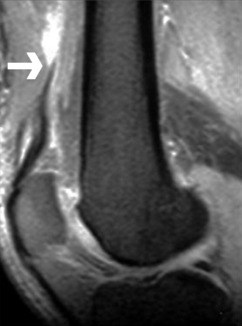

Avulsion of the quadriceps tendon from the upper pole of the patella occurs mainly in elderly men, in whom the quadriceps tendon is often degenerate. It is not a common injury. The clinical diagnosis is seldom in doubt, but can be confirmed by ultrasound or MR scanning (Fig. 18.30). The tendon should be re-attached to the bone by strong non-absorbable sutures passed through drill holes near the upper border of the patella.

Disruption through patella

This is the usual site of rupture, and it forms a common variety of fractured patella. The injury occurs mainly in adults of middle age. If the patella is cleanly broken into two pieces the fragments should be fixed together by a screw or cerclage wiring, with reinforcing sutures through the torn soft tissues on either side of the patella. If there are multiple patellar fragments, these should be excised and the quadriceps expansion repaired by sutures.

1 Robert Osgood (1873–1956) was a famous American orthopaedic surgeon, but was working as a radiologist in Boston Children’s Hospital when he described the condition in 1903. He worked with Robert Jones in England during the First World War and helped him found the British Orthopaedic Association.

Apophysitis of the tibial tubercle is a childhood affection in which the tibial tubercle becomes enlarged and temporarily painful. Often known as Osgood–Schlatter’s disease, it was formerly regarded as an example of osteochondritis juvenilis (p. 130), but it is now generally agreed that it is nothing more than a strain of the developing tibial tubercle, from the pull of the patellar tendon.

Radiographs show enlargement and sometimes fragmentation of the tibial tubercle (Fig. 18.31).

PREPATELLAR BURSITIS

Types. There are two types of prepatellar bursitis:

Irritative prepatellar bursitis

Clinical features. There is a softly fluctuant swelling in front of the lower part of the patella, which is clearly demarcated. It is manifestly confined to a plane in front of the joint, and the joint itself is unaffected.

POPLITEAL CYSTS

Baker’s cyst1

A Baker’s cyst is simply a herniation of the synovial cavity of the knee, with the formation of a fluid-filled sac extending backwards and downwards (Fig. 18.32A). It is not a primary condition but is always secondary to a disorder of the knee with persistent synovial effusion, such as rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. In long-standing cases the hernial sac is much elongated, and may extend a considerable distance down the calf. Occasionally this may rupture and the resultant pain and local tenderness may be mistaken for a deep vein thrombosis.

Imaging. Where there is any uncertainty as to the diagnosis, it may be necessary to use ultrasound or MRI scanning to establish the nature and extent of the lesion (Fig. 18.32B).

1 Augusto Pellegrini (1877–1958), who was Professor of Surgery in Florence and later Perugia, described post-traumatic ossification of knee ligaments in 1905. He was also a pioneer in the development of powered prostheses for the upper limb.

Pellegrini–Stieda’s disease is the name sometimes used to describe ossification in the subligamentous haematoma after partial avulsion of the medial ligament from the medial condyle of the femur. Clinically there is persistent discomfort at the medial side of the knee after an injury to the medial ligament. There are thickening and slight tenderness over the site of attachment of the ligament to the medial femoral condyle. Radiographs show a thin plaque of new bone close to the medial condyle.

Treatment is by active mobilising and muscle-strengthening exercises.

Calcified deposit in medial ligament

It is probable that some supposed cases of Pellegrini–Stieda’s disease are in fact examples of calcified deposit within the medial ligament. A similar deposit may occur in the lateral ligament. These lesions are homologous with the calcified deposit that occurs more commonly in the supraspinatus tendon at the shoulder (p. 269). If the symptoms are acute the calcified material should be removed by aspiration or by operation. A steroid injection may also be of benefit in some patients.

EXTRINSIC DISORDERS WITH REFERRED SYMPTOMS IN THE KNEE

From time to time patients are seen whose main complaint is of pain in the knee, but local examination reveals no satisfactory explanation for it. In such cases the possibility that the pain is referred from a disorder distant from the knee should always be considered. The commonest source of such referred pain is a disorder of the hip, particularly a slipped capital femoral epiphysis in children or osteoarthritis in the adult. Much less often a disorder of the spine is responsible, though referred pain to the leg from pressure of prolapsed disc material on lumbo-sacral nerve roots may sometimes cause confusion.