The Therapist-Driven Protocol Program and the Role of the Respiratory Care Practitioner

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• Describe the Therapist-Driven Protocol (TDP) program and the role of the respiratory care practitioner.

• Discuss the knowledge base required for a successful TDP program.

• Explain the assessment process skills required for a successful TDP program, and include the following:

• The clinical manifestations, assessments, and treatment selections made by the respiratory care practitioner

• The frequency at which a respiratory therapy modality can be determined in response to a severity assessment

• Describe the following essential cornerstone respiratory protocols for a successful TDP program:

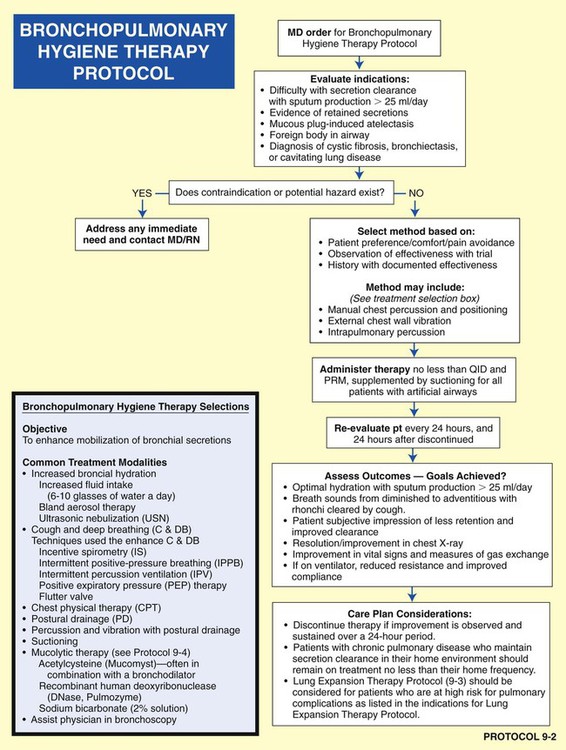

• Bronchopulmonary hygiene therapy protocol

• Lung expansion therapy protocol

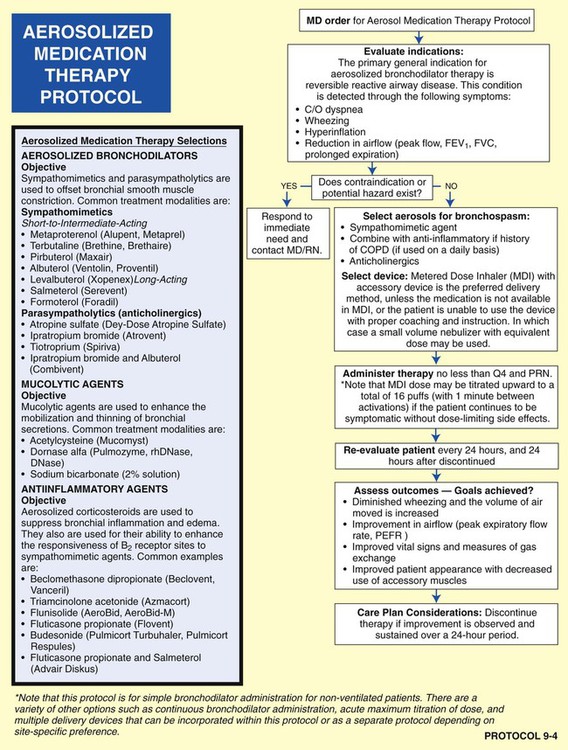

• Aerosolized medication therapy protocol

• Mechanical ventilation protocol

• Mechanical ventilation weaning protocol

• Describe ventilatory management in catastrophes.

• List the following common anatomic alterations of the lungs:

• Increased alveolar-capillary membrane thickness

• Excessive bronchial secretions

• Distal airway and alveolar weakening

• Analyze the clinical scenarios—chain of events—activated by the common anatomic alterations of the lungs, and include the following:

• Anatomic alterations of the lungs

• Pathophysiologic mechanisms activated

• Treatment protocols used to correct the problem

• Identify the most common anatomic alterations associated with the respiratory disorders presented in this textbook.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

Introduction

• Deliver individualized diagnostic and therapeutic respiratory care to patients

• Assist the physician with evaluating patients’ respiratory care needs and optimize the allocation of respiratory care services

• Determine the indications for respiratory therapy and the appropriate modalities for providing high-quality, cost-effective care that improves patient outcomes and decreases length of stay

• Empower respiratory care practitioners to allocate care using sign- and symptom-based algorithms for respiratory treatment

Unfortunately, the implementation of TDPs throughout the United States has been slow. In 2008 the AARC Protocol Implementation Committee conducted a survey to evaluate the barriers to protocol implementation. Over 450 respiratory managers responded to the survey. Despite the overwhelming evidence that protocols clearly improve outcomes and reduce cost, the survey showed that less than 50% of respiratory care was provided by protocols. About 75% of the respondents had at least one protocol in operation. The majority of the hospitals did not have a comprehensive program in place. According to the managers, the medical directors, managers of the department, nurses, and administrators were not perceived as barriers. The biggest barrier to the implementation of protocols was perceived to be the medical staff. The primary reason for the medical staff’s resistance was perceived to be that “staff therapists did not have the skills (e.g., assessment skills) to function under protocols.” The AARC Protocol Implementation Committee states that “[this] perception must change… .”*

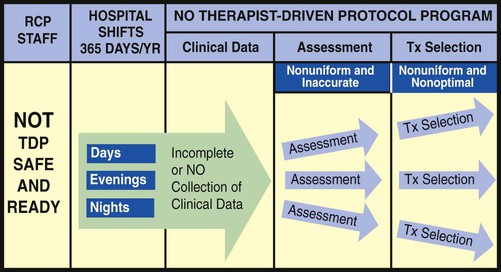

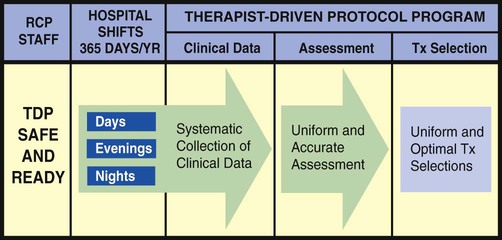

The essential components of a good TDP program do not come easy. This is because a strong TDP program promises that the respiratory care practitioner, who is identified as “TDP safe and ready,” be qualified to (1) systematically collect the appropriate clinical data, (2) formulate a uniform and accurate assessment, and (3) select a uniform and optimal treatment within the limits set by the protocol (Figure 9-1). The converse, however, is also true: When the respiratory care practitioner is not “TDP safe and ready,” the collection of clinical data is not done at all or is incomplete. As a result, nonuniform or inaccurate assessments are made, resulting in nonuniform or inaccurate treatment selections (Figure 9-2). This inappropriate and ineffective type of respiratory therapy leads to the misallocation of care, the administration of unneeded care, and—most important—the nonprovision of needed patient care. The bottom line is poor-quality patient care and unnecessary costs. To be sure, the development and implementation of a strong TDP program require some fundamental knowledge, training, and practice, but the benefits are worth the price. The essential components of a good TDP program are discussed in the following paragraphs.

The “Knowledge Base” Required for a Successful Therapist-Driven Protocol Program

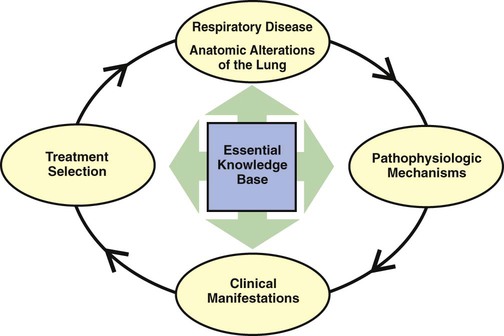

As shown in Figure 9-3, the essential knowledge base for a successful TDP program includes (1) the anatomic alterations of the lungs caused by common respiratory disorders, (2) the major pathophysiologic mechanisms activated throughout the respiratory and cardiac systems as a result of the anatomic alterations, (3) the common clinical manifestations that develop as a result of the activated pathophysiologic mechanisms, and (4) the treatment modalities used to correct them. In other words, the clinical manifestations demonstrated by the patient do not arbitrarily appear but are the result of anatomic lung alterations and pathophysiologic events.

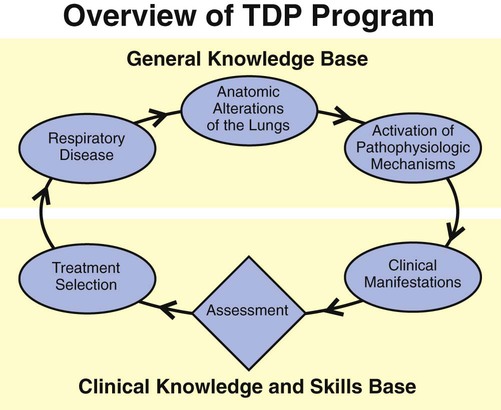

The “Assessment Process Skills” Required for a Successful Therapist-Driven Protocol Program

Using the knowledge base described above, the respiratory care practitioner must also be competent in performing the actual assessment process. This means that the practitioner can (1) quickly and systematically gather the clinical information demonstrated by the patient, (2) formulate an accurate assessment of the clinical data (i.e., identify the cause and severity of the problem), (3) select an optimal treatment modality, and (4) document this process quickly, clearly, and precisely. In the clinical setting, the practice—and mastery—of the assessment process is absolutely central and essential to the success of a good TDP program (Figure 9-4). In other words, immediately after the respiratory care practitioner identifies the appropriate clinical manifestations (clinical indicators), an assessment of the data must be performed, and a treatment plan must be formulated. For the most part the assessment is primarily directed at the anatomic alterations of the lungs that are causing the clinical indicators (e.g., bronchospasm) and the severity of the clinical indicators.

For example, an appropriate assessment for the clinical indicator of wheezing might be bronchospasm—the anatomic alteration of the lungs. If the practitioner assesses the cause of the wheezing correctly as bronchospasm, then the correct treatment selection would be a bronchodilator treatment from the Aerosolized Medication Therapy Protocol (see Protocol 9-4, page 122). If, however, the cause of the wheezing is correctly assessed to be excessive airway secretions, then the appropriate treatment plan would entail a specific treatment modality under the Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol, such as cough and deep breathing or chest physical therapy (see Protocol 9-2, page 120).

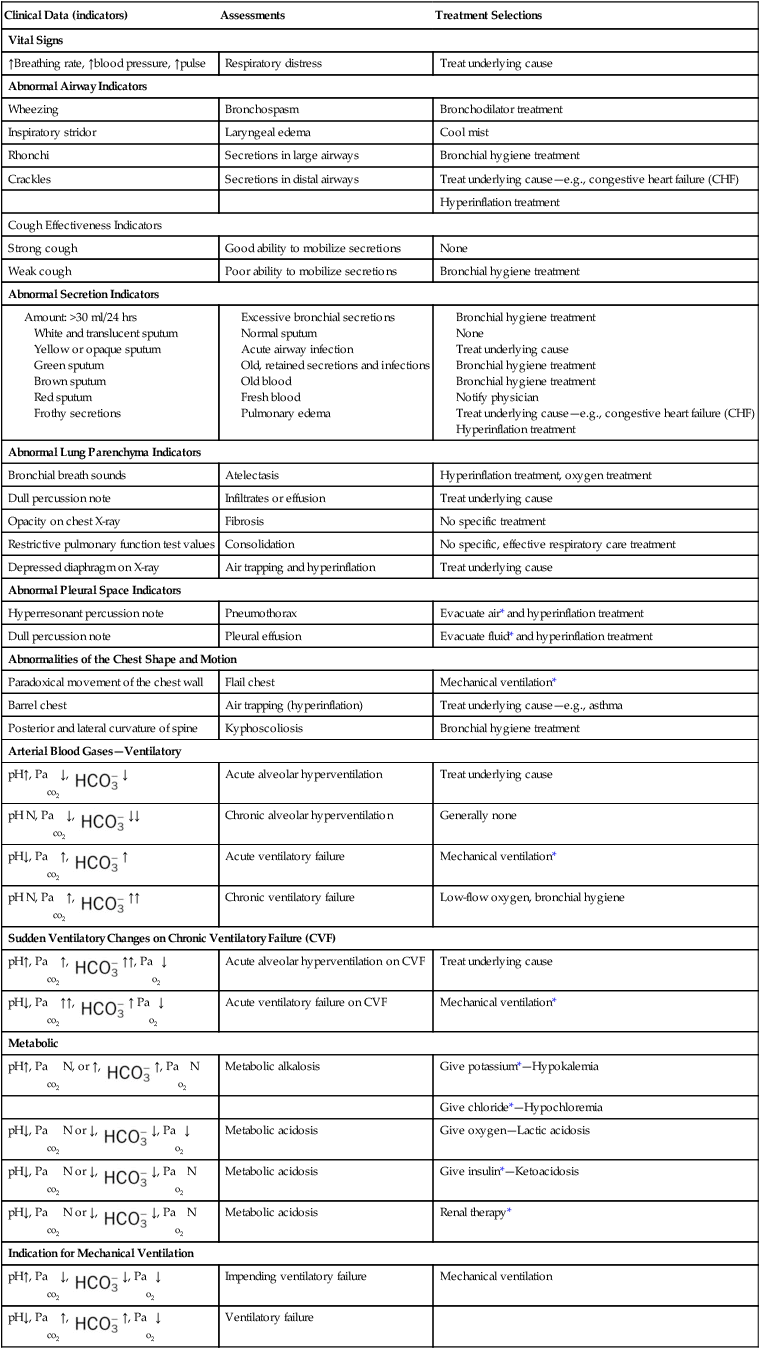

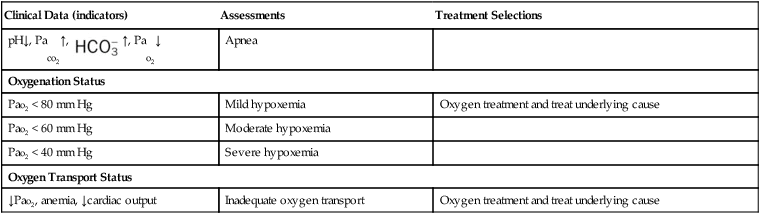

Table 9-1 illustrates common clinical manifestations (i.e., clinical indicators), assessments, and treatment selections routinely made by the respiratory care practitioner.

TABLE 9-1

| Clinical Data (indicators) | Assessments | Treatment Selections |

| Vital Signs | ||

| ↑Breathing rate, ↑blood pressure, ↑pulse | Respiratory distress | Treat underlying cause |

| Abnormal Airway Indicators | ||

| Wheezing | Bronchospasm | Bronchodilator treatment |

| Inspiratory stridor | Laryngeal edema | Cool mist |

| Rhonchi | Secretions in large airways | Bronchial hygiene treatment |

| Crackles | Secretions in distal airways | Treat underlying cause—e.g., congestive heart failure (CHF) |

| Hyperinflation treatment | ||

| Cough Effectiveness Indicators | ||

| Strong cough | Good ability to mobilize secretions | None |

| Weak cough | Poor ability to mobilize secretions | Bronchial hygiene treatment |

| Abnormal Secretion Indicators | ||

↓

↓ ↓↓

↓↓ ↑

↑ ↑↑

↑↑ ↑↑, Pao2↓

↑↑, Pao2↓ ↑ Pao2↓

↑ Pao2↓ ↑, Pao2 N

↑, Pao2 N ↓, Pao2↓

↓, Pao2↓ ↓, Pao2 N

↓, Pao2 N ↓, Pao2 N

↓, Pao2 N ↓, Pao2↓

↓, Pao2↓ ↑, Pao2↓

↑, Pao2↓ ↑, Pao2↓

↑, Pao2↓

*These procedures should be performed only as ordered by the physician.

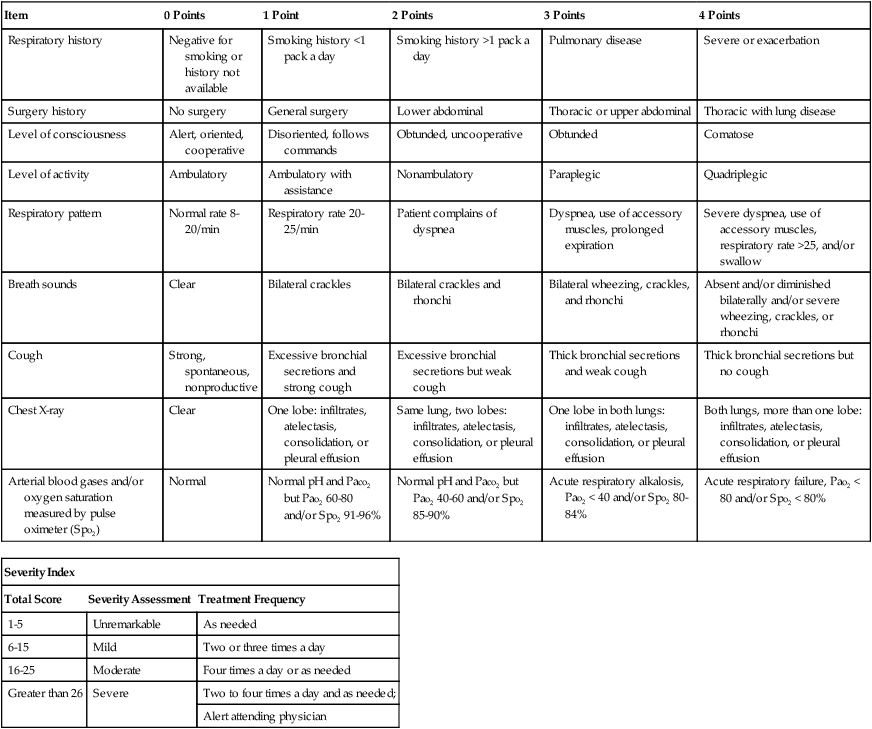

Severity Assessment

The frequency at which a respiratory therapy modality is to be administered is just as important as the correct selection of a respiratory therapy treatment. Often the frequency of treatment must be up-regulated or down-regulated on a shift-by-shift, hour-to-hour, minute-to-minute, or even (in life-threatening situations) second-to-second basis. Such frequency changes must be made in response to a severity assessment. In a good TDP program, the well-seasoned respiratory care practitioner routinely and systematically documents many severity assessments throughout each working day. For the new practitioner, however, a predesigned Severity Assessment Rating Form may be used to enhance this important part of the assessment process. One excellent, semiquantitative method of accomplishing this is illustrated in Table 9-2. The clinical application of this severity assessment is provided in the following case example.

TABLE 9-2

Respiratory Care Protocol Severity Assessment

| Item | 0 Points | 1 Point | 2 Points | 3 Points | 4 Points |

| Respiratory history | Negative for smoking or history not available | Smoking history <1 pack a day | Smoking history >1 pack a day | Pulmonary disease | Severe or exacerbation |

| Surgery history | No surgery | General surgery | Lower abdominal | Thoracic or upper abdominal | Thoracic with lung disease |

| Level of consciousness | Alert, oriented, cooperative | Disoriented, follows commands | Obtunded, uncooperative | Obtunded | Comatose |

| Level of activity | Ambulatory | Ambulatory with assistance | Nonambulatory | Paraplegic | Quadriplegic |

| Respiratory pattern | Normal rate 8-20/min | Respiratory rate 20-25/min | Patient complains of dyspnea | Dyspnea, use of accessory muscles, prolonged expiration | Severe dyspnea, use of accessory muscles, respiratory rate >25, and/or swallow |

| Breath sounds | Clear | Bilateral crackles | Bilateral crackles and rhonchi | Bilateral wheezing, crackles, and rhonchi | Absent and/or diminished bilaterally and/or severe wheezing, crackles, or rhonchi |

| Cough | Strong, spontaneous, nonproductive | Excessive bronchial secretions and strong cough | Excessive bronchial secretions but weak cough | Thick bronchial secretions and weak cough | Thick bronchial secretions but no cough |

| Chest X-ray | Clear | One lobe: infiltrates, atelectasis, consolidation, or pleural effusion | Same lung, two lobes: infiltrates, atelectasis, consolidation, or pleural effusion | One lobe in both lungs: infiltrates, atelectasis, consolidation, or pleural effusion | Both lungs, more than one lobe: infiltrates, atelectasis, consolidation, or pleural effusion |

| Arterial blood gases and/or oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximeter (Spo2) | Normal | Normal pH and Paco2 but Pao2 60-80 and/or Spo2 91-96% | Normal pH and Paco2 but Pao2 40-60 and/or Spo2 85-90% | Acute respiratory alkalosis, Pao2 < 40 and/or Spo2 80-84% | Acute respiratory failure, Pao2 < 80 and/or Spo2 < 80% |

| Severity Index | ||

| Total Score | Severity Assessment | Treatment Frequency |

| 1-5 | Unremarkable | As needed |

| 6-15 | Mild | Two or three times a day |

| 16-25 | Moderate | Four times a day or as needed |

| Greater than 26 | Severe | Two to four times a day and as needed; |

| Alert attending physician | ||

The Essential Cornerstone Respiratory Protocols for a Successful Therapist-Driven Protocol Program

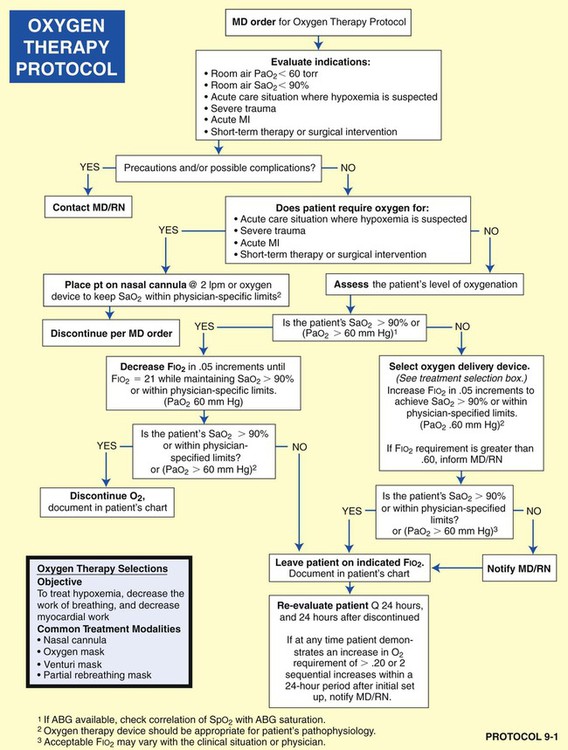

• Oxygen Therapy Protocol (Protocol 9-1)

• Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol (Protocol 9-2)

• Aerosolized Medication Therapy Protocol (Protocol 9-4)

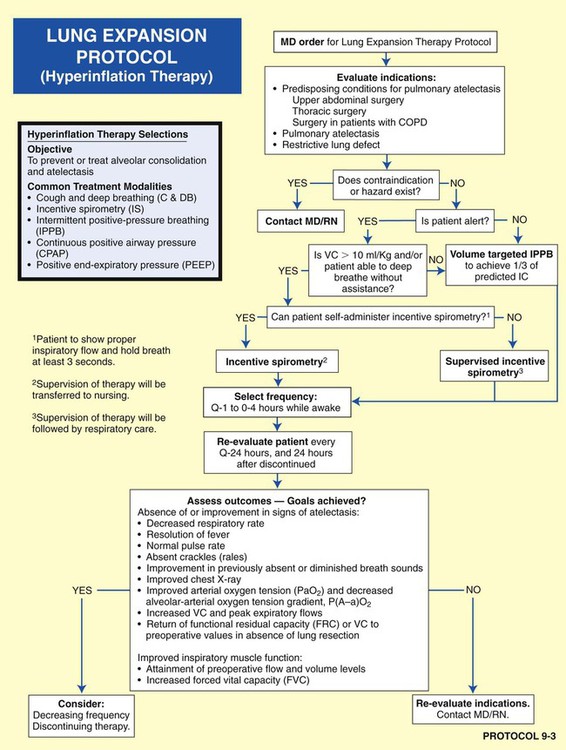

• Lung Expansion Therapy Protocol (Protocol 9-3)

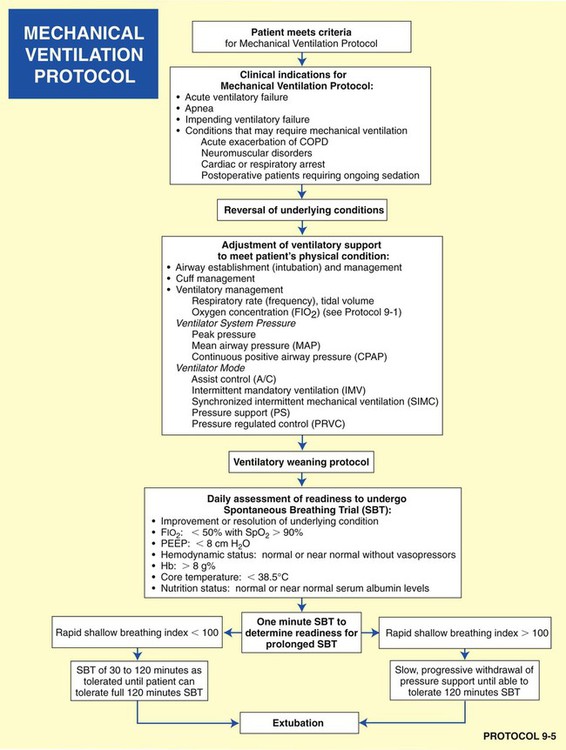

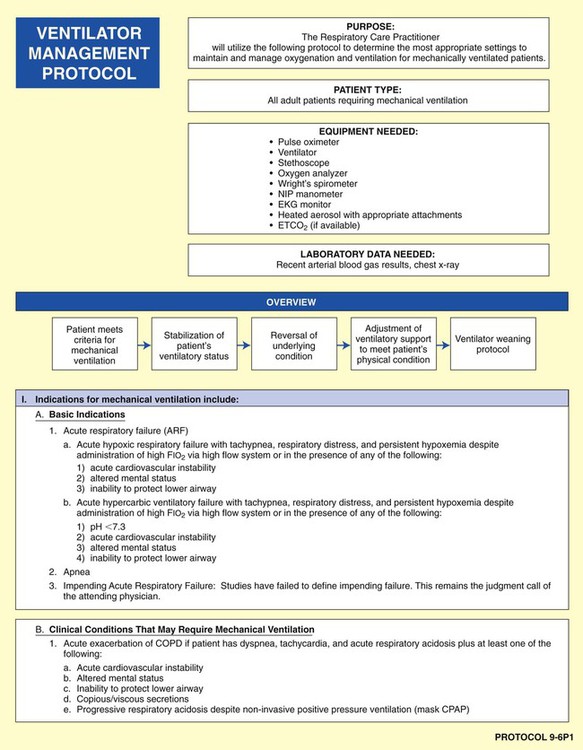

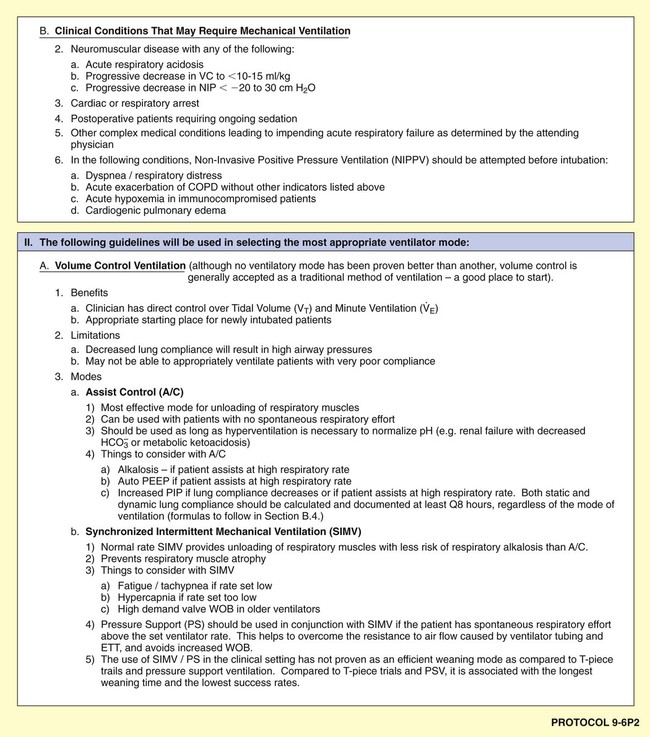

• Mechanical Ventilation Protocol (Protocol 9-5 and Protocol 9-6)

• Mechanical Ventilation Weaning Protocol (Protocol 9-7)

As shown in the algorithms in Protocols 9-1 through 9-7, a step-by step, branching logic process directs the practitioner to (1) gather clinical data (clinical indicators), (2) make assessment decisions based on the clinical data, and (3) either start, up-regulate, down-regulate, or discontinue a treatment modality. In fact, the primary reason a good TDP program works is because a specific treatment modality cannot be started, stopped, or modified unless there are specific—and measurable—clinical indicators identified to justify the assessment and treatment decision.

The treatment selections outlined in each of the listed protocols are based on current AARC’s Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs), which provide the most recent scientific evidence that justifies the administration of a specific treatment modality. Using the evidence-based method mandated by the scientific community, CPGs provide the indications, contraindications, hazards and complications, assessment of need, assessment of outcome, and appropriate monitoring techniques used for specific therapy modalities. In other words, the CPGs are the gold standards used by the respiratory care practitioner to start, adjust, or discontinue a specific treatment modality. In Box 9-1, excerpts from the AARC’s CPG on oxygen therapy for adults in the acute care facility provide a representative example of a CPG—and, more important, the scientific basis for the Oxygen Therapy Protocol (Protocol 9-1).*

For example, the implementation of the Lung Expansion Therapy Protocol (Protocol 9-3) would likely be indicated after thoracic surgery to prevent, or correct, atelectasis. If the patient were unconscious or unable to follow directions, a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) mask would be a more appropriate treatment selection (under the Lung Expansion Therapy Protocol) than, say, incentive spirometry—even though both are designed to treat or prevent atelectasis. In this example, the CPAP mask therapy would be more expensive but more appropriate than the less expensive incentive spirometry.

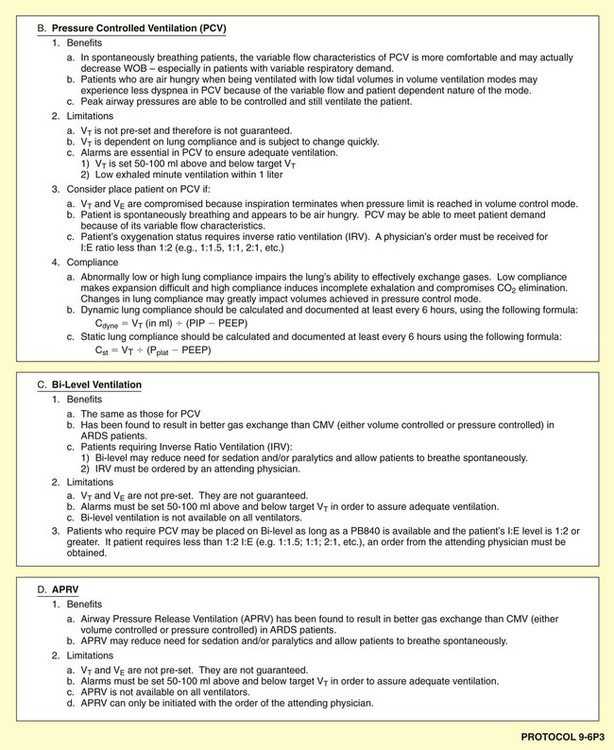

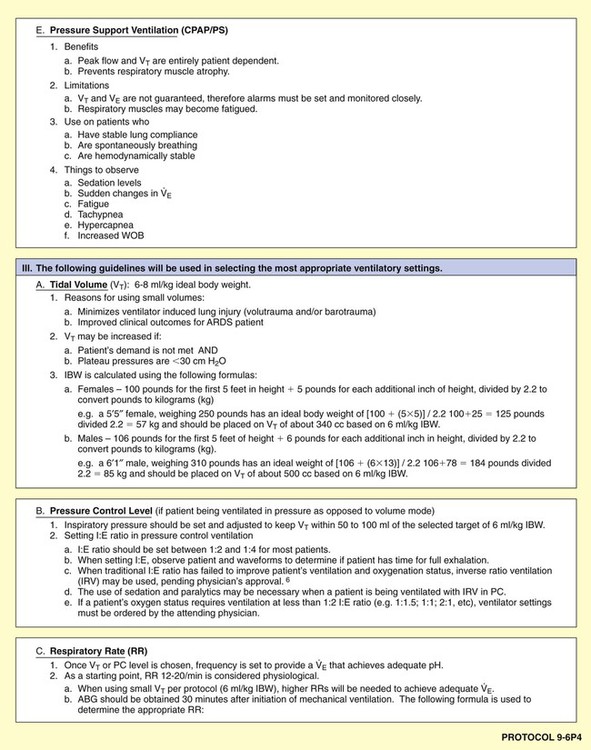

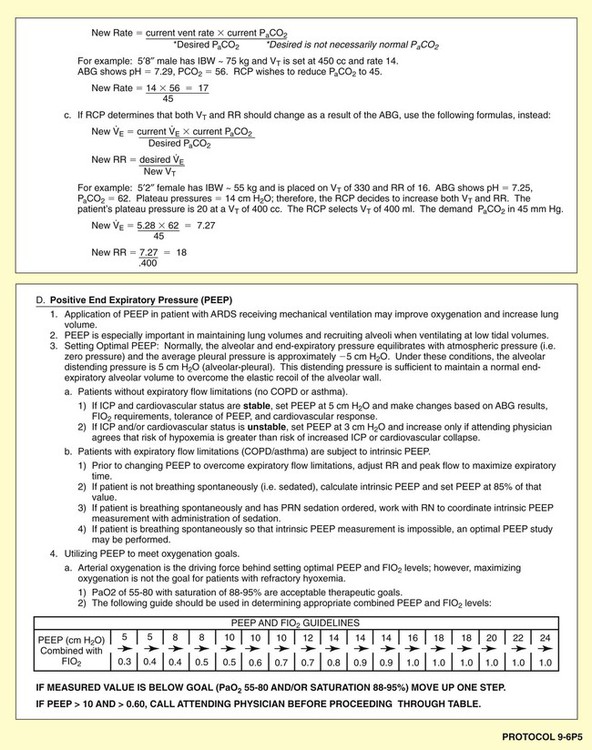

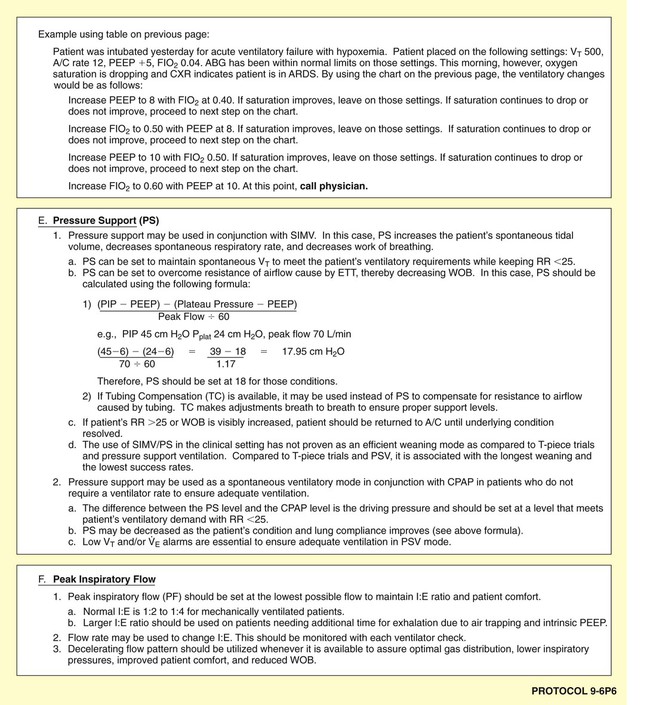

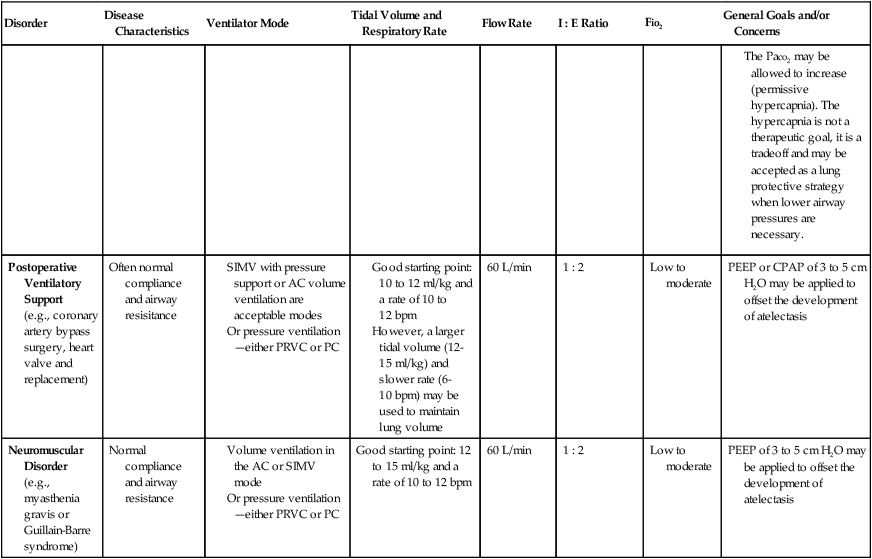

Mechanical Ventilation Protocol

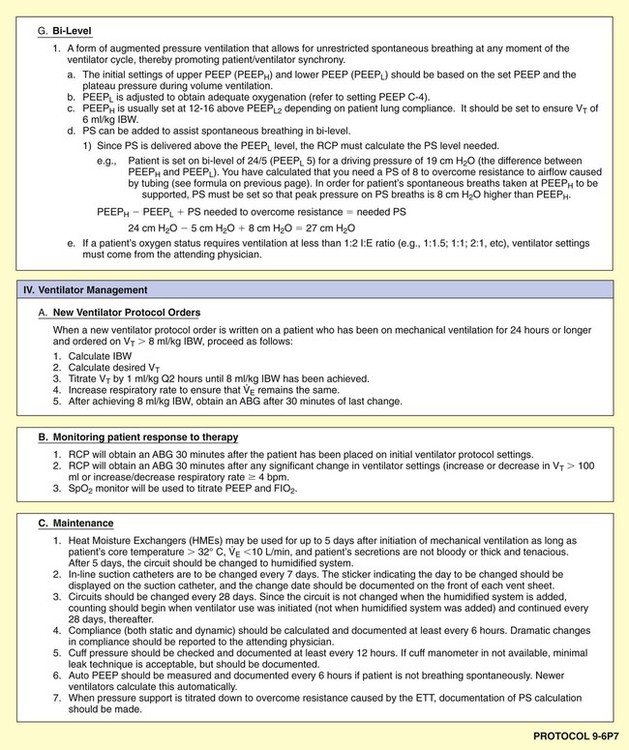

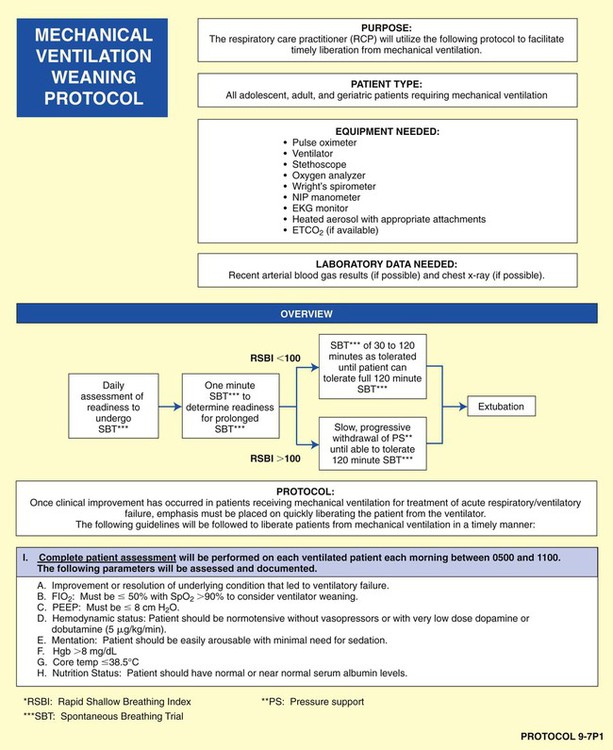

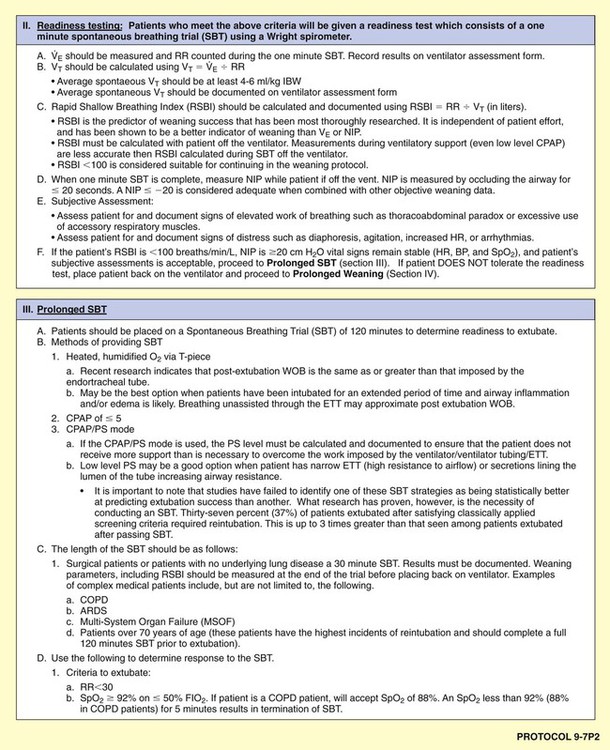

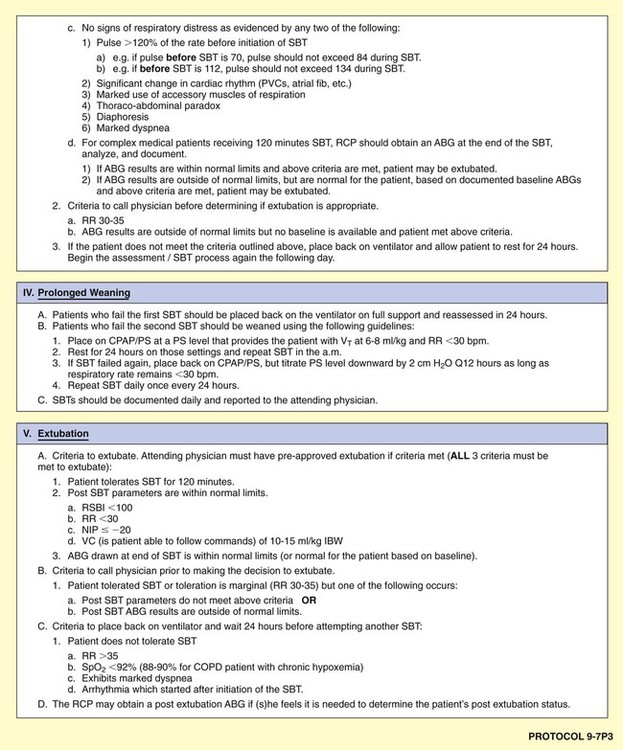

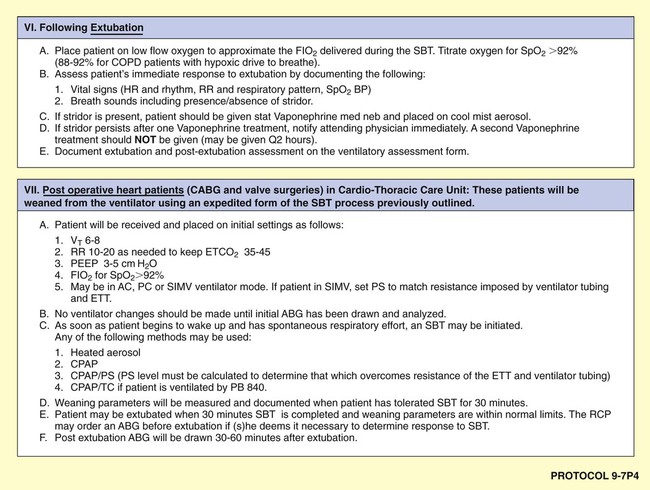

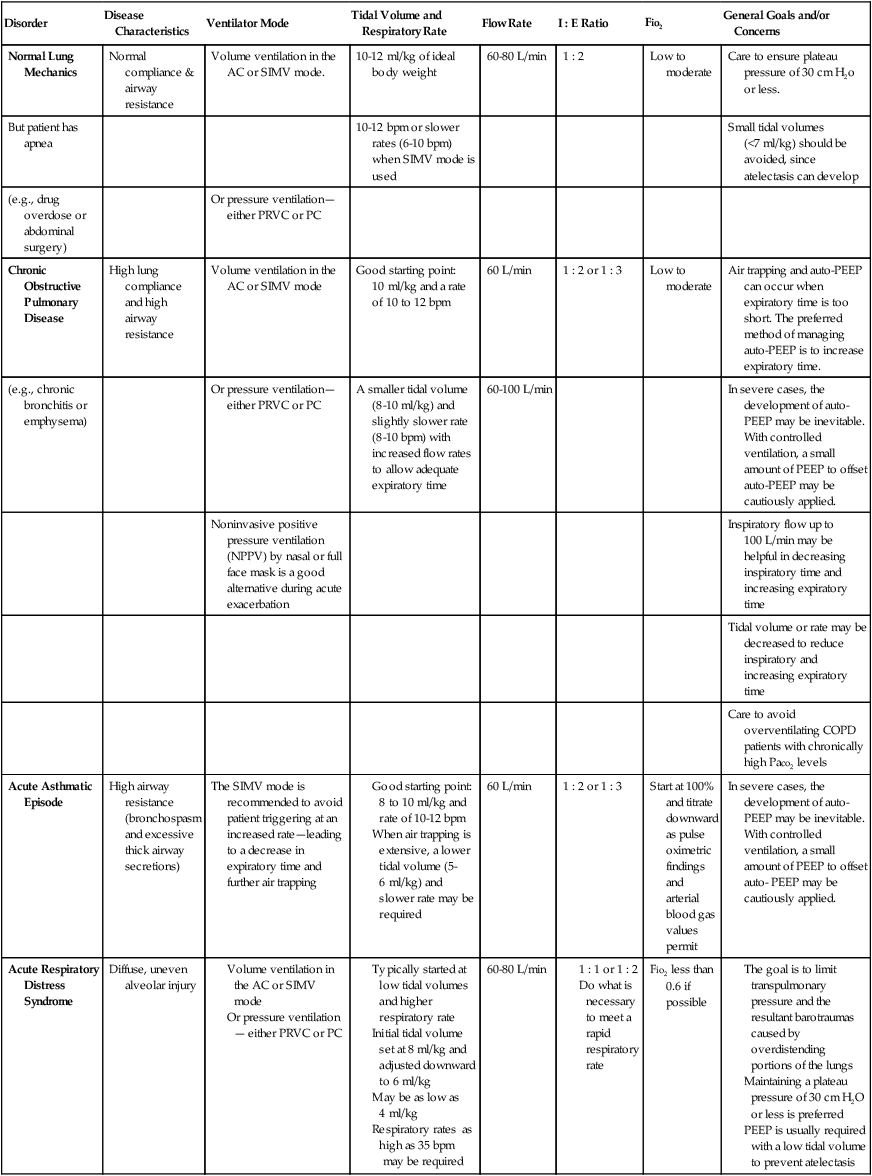

Although there are a number of good ventilatory management strategies used to treat specific respiratory disorders, the need for a standardized approach to ventilator management has required the development of Mechanical Ventilation Protocols. Protocol 9-5 provides an example of a Mechanical Ventilation Protocol. Protocol 9-6 further illustrates a more comprehensive—and operational—protocol for Mechanical Ventilator Management, and Protocol 9-7 illustrates an example of a comprehensive operational Mechanical Ventilation Weaning Protocol.*

Although most Mechanical Ventilation Protocols require the respiratory care practitioner to select a ventilator mode on the basis of specific patient needs, it is not the intent of this textbook to fully review or discuss the various ventilator modes and weaning strategies. Table 9-3, however, does provide an excellent overview of common ventilatory management strategies and good starting points used to treat specific pulmonary disorders.

TABLE 9-3

Common Ventilatory Management Strategies Used to Treat Specific Disorders (Good Starting Points)

| Disorder | Disease Characteristics | Ventilator Mode | Tidal Volume and Respiratory Rate | Flow Rate | I : E Ratio | Fio2 | General Goals and/or Concerns |

| Normal Lung Mechanics | Normal compliance & airway resistance | Volume ventilation in the AC or SIMV mode. | 10-12 ml/kg of ideal body weight | 60-80 L/min | 1 : 2 | Low to moderate | Care to ensure plateau pressure of 30 cm H2o or less. |

| But patient has apnea | 10-12 bpm or slower rates (6-10 bpm) when SIMV mode is used | Small tidal volumes (<7 ml/kg) should be avoided, since atelectasis can develop | |||||

| (e.g., drug overdose or abdominal surgery) | Or pressure ventilation—either PRVC or PC | ||||||

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | High lung compliance and high airway resistance | Volume ventilation in the AC or SIMV mode | Good starting point: 10 ml/kg and a rate of 10 to 12 bpm | 60 L/min | 1 : 2 or 1 : 3 | Low to moderate | Air trapping and auto-PEEP can occur when expiratory time is too short. The preferred method of managing auto-PEEP is to increase expiratory time. |

| (e.g., chronic bronchitis or emphysema) | Or pressure ventilation—either PRVC or PC | A smaller tidal volume (8-10 ml/kg) and slightly slower rate (8-10 bpm) with increased flow rates to allow adequate expiratory time | 60-100 L/min | In severe cases, the development of auto-PEEP may be inevitable. With controlled ventilation, a small amount of PEEP to offset auto-PEEP may be cautiously applied. | |||

| Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) by nasal or full face mask is a good alternative during acute exacerbation | Inspiratory flow up to 100 L/min may be helpful in decreasing inspiratory time and increasing expiratory time | ||||||

| Tidal volume or rate may be decreased to reduce inspiratory and increasing expiratory time | |||||||

| Care to avoid overventilating COPD patients with chronically high Paco2 levels | |||||||

| Acute Asthmatic Episode | High airway resistance (bronchospasm and excessive thick airway secretions) | The SIMV mode is recommended to avoid patient triggering at an increased rate—leading to a decrease in expiratory time and further air trapping |

(e.g., coronary artery bypass surgery, heart valve and replacement)

(e.g., myasthenia gravis or Guillain-Barre syndrome)

Ventilatory Management in Catastrophes

Figure 9-5, a photograph taken during the great poliomyelitis epidemic in the early 1950s (over 50,000 people were stricken), reminds the reader of a need for such intervention. Note the nurse-to-patient ratio of 1 : 2. At the time, each nurse was ready to step in and manually operate the “iron lungs” of two patients in the event of a power outage. Today, it is very unlikely that our health-care system could adequately provide this type of ventilator care and coverage.

With the realization that many factors may result in a large demand for ventilator management, some thought is now being offered in the literature that suggests how this might be done. The choices and alternatives are grim ones and are illustrated in a representative three-tier criteria system provided in Box 9-2. As shown, Tier 1 is directed only to acute ventilatory failure with shock and multiple organ dysfunction. Tier 2 presents criteria for high potential for death, prolonged ventilation, and high levels of resource use. Tier 3 criteria may entail additional restrictions or a scoring system and are implemented to maintain consistent standards of care.*

Overview Summary of a Good Therapist-Driven Protocol Program

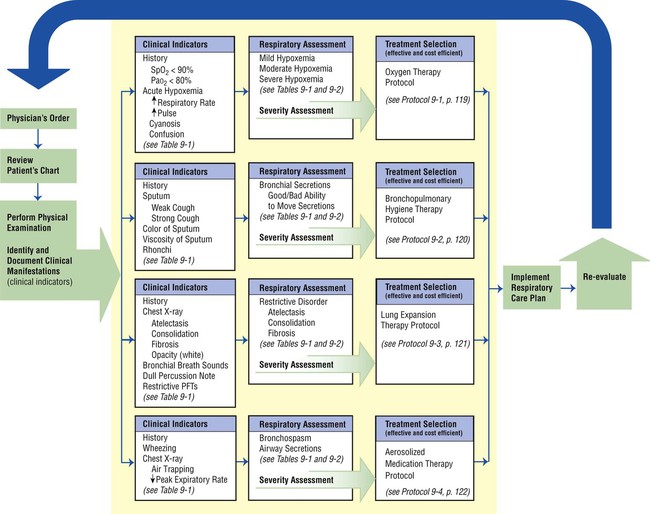

Figure 9-6 provides an overview of the essential components of a good TDP program. As illustrated, the implementation of every respiratory care plan must be directly linked to (1) a physician’s order, (2) the identification and documentation of specific clinical indicators (obtained from both the patient’s chart and physical examination), (3) a bedside respiratory assessment and severity assessment, (4) a treatment selection that is both therapeutic and cost-efficient, and (5) the reevaluation of the patient’s response to the treatment.

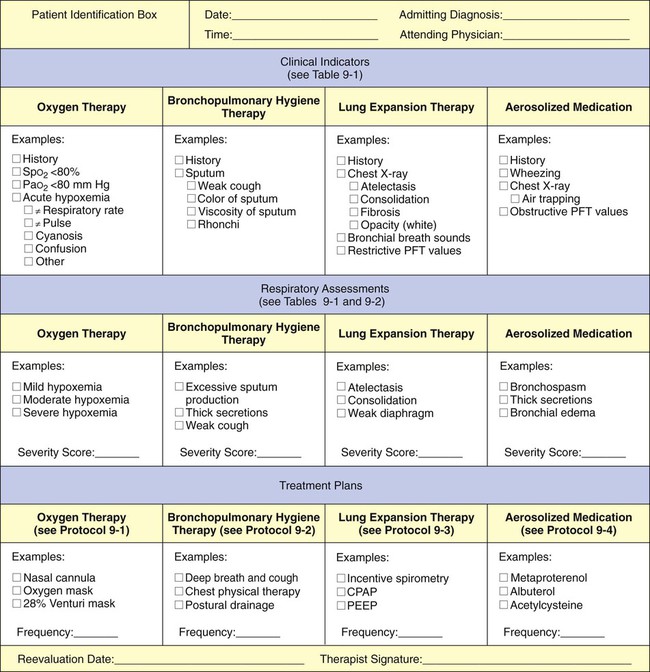

This step-by-step process mandates that the respiratory care practitioner (1) have a strong knowledge base of the major respiratory disorders, and (2) be competent in the actual assessment process (see Figure 9-4). Figure 9-7 provides an assessment form with common examples for each category (i.e., clinical indicators, respiratory assessments, and treatment plans). The examples shown in Figure 9-6 can easily be transferred to the subjective-objective-assessment-plan (SOAP) format. The SOAP format used in the assessment of respiratory diseases is discussed in more detail in Chapter 10.

Common Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

Although the respiratory care practitioner may at some time treat one or two cases of every respiratory disorder presented in this book, most of the respiratory care practitioner’s professional career will be spent caring for patients with only a few of them. For example, the diagnosis-related group (DRG) and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-9) identification systems show that more than 80% of the respiratory care practitioner’s work is concerned with intelligent assessment and treatment selection for a relatively short list of respiratory illnesses (Table 9-4).

TABLE 9-4

| Respiratory Disorder | DRG Number* | ICD-10 Code† |

| Chronic bronchitis | 088 | 491.1, 491.9 |

| Emphysema | 088 | 492.8 |

| Asthma | 096 | 493.0 |

| Acute pneumonia | 079, 089, 090 | (see below) |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 079 | 507.0 |

| Atelectasis | 101/102 | 518.89 |

| Adult respiratory distress syndrome | 099/102 | 518.82 |

| Interstitial fibrosis | 089 | 515.0 |

| Pulmonary edema/congestive heart failure | 127 | 402.91 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 087 | 518.81 |

| Respiratory failure with ventilatory support | 475 | 96.7 |

| Respiratory failure/tracheostomy/ventilatory support | 483 | 96.72/31.1 |

*Respiratory disorders can be identified by their respective diagnosis-related group (DRG). DRG is an identification system used to categorize and document diseases, primarily for use in health care reimbursement (such as Medicaid and Medicare). Patients are routinely assigned a DRG based on their admitting diagnosis, and each DRG communicates information about patients. Because the use of DRGs is prevalent, respiratory care practitioners should recognize and understand the DRGs that they will commonly encounter.

†The ICD-10 code numbers are used for reimbursement with other third party payers. The ICD-10 system is more specific than the DRG system. For example, pneumococcal pneumonia is listed as ICD # 418.0, Haemophilus influenzae is ICD # 482.2, etc.

Therefore the most common anatomic alterations of the lungs treated by the respiratory care practitioner can be derived by recognizing the most common DRG respiratory disorders identified in Table 9-4. The major anatomic alterations include (1) atelectasis (e.g., which can occur from mucous plugging, upper abdominal surgery, or pneumothorax), (2) alveolar consolidation (e.g., pneumonia), (3) increased alveolar-capillary membrane thickness (e.g., acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS], pneumoconiosis, or pulmonary edema), (4) bronchospasm (e.g., asthma), (5) excessive bronchial secretions (e.g., chronic bronchitis, asthma, pulmonary edema), and (6) distal airway and alveolar weakening (e.g., emphysema). Each of these anatomic alterations of the lung in turn leads to a chain of events that can be summarized in the following clinical scenarios.

Clinical Scenarios Activated by Common Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

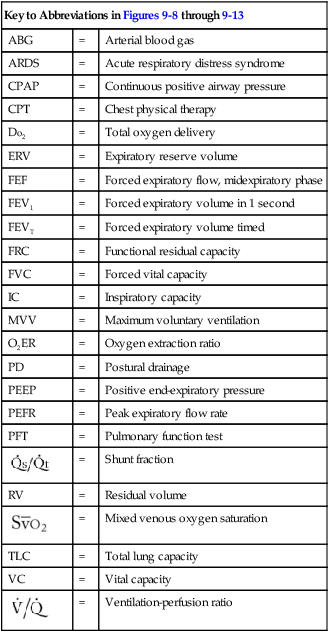

For the purposes of this text, we have chosen to refer to the interrelationship among the major anatomic alterations of the lung, the pathophysiologic mechanisms, and the clinical manifestations that result as “clinical scenarios.” Specific anatomic alterations of the lung (such as the ones listed previously) lead to the activation of specific and predictable pathophysiologic mechanisms and to their effects. The more common pathophysiologic mechanisms are listed in Box 9-3. The pathophysiologic mechanisms in turn activate specific and predictable clinical manifestations (see Figure 9-3). To enhance the reader’s knowledge and understanding of commonly encountered respiratory disorders, clinical scenarios for the anatomic alterations presented in the following paragraphs are provided.*

| Key to Abbreviations in Figures 9-8 through 9-13 | ||

| ABG | = | Arterial blood gas |

| ARDS | = | Acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| CPAP | = | Continuous positive airway pressure |

| CPT | = | Chest physical therapy |

| Do2 | = | Total oxygen delivery |

| ERV | = | Expiratory reserve volume |

| FEF | = | Forced expiratory flow, midexpiratory phase |

| FEV1 | = | Forced expiratory volume in 1 second |

| FEVT | = | Forced expiratory volume timed |

| FRC | = | Functional residual capacity |

| FVC | = | Forced vital capacity |

| IC | = | Inspiratory capacity |

| MVV | = | Maximum voluntary ventilation |

| O2ER | = | Oxygen extraction ratio |

| PD | = | Postural drainage |

| PEEP | = | Positive end-expiratory pressure |

| PEFR | = | Peak expiratory flow rate |

| PFT | = | Pulmonary function test |

|

= | Shunt fraction |

| RV | = | Residual volume |

|

= | Mixed venous oxygen saturation |

| TLC | = | Total lung capacity |

| VC | = | Vital capacity |

|

= | Ventilation-perfusion ratio |

Atelectasis

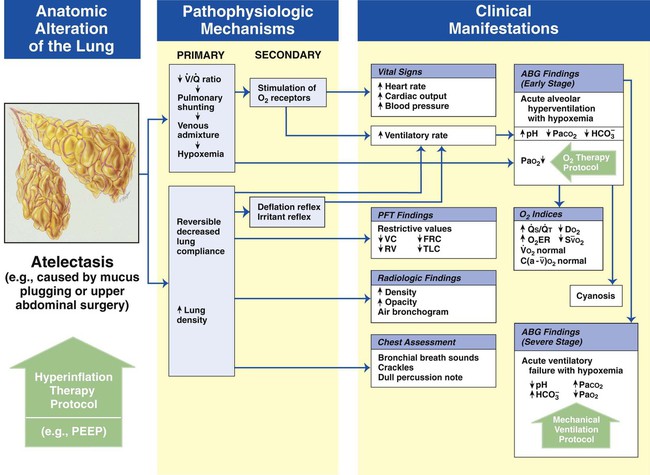

Figure 9-8 shows the pathophysiologic mechanisms caused by atelectasis (e.g., from a pneumothorax), the clinical manifestations that result, and the treatment protocols used to offset them. The hypoxemia that results from atelectasis is caused by capillary shunting. This type of hypoxemia is often refractory to oxygen therapy. Therefore the implementation of the Lung Expansion Therapy Protocol may be more beneficial in the treatment of hypoxemia than the Oxygen Therapy Protocol in such a patient.

Alveolar Consolidation

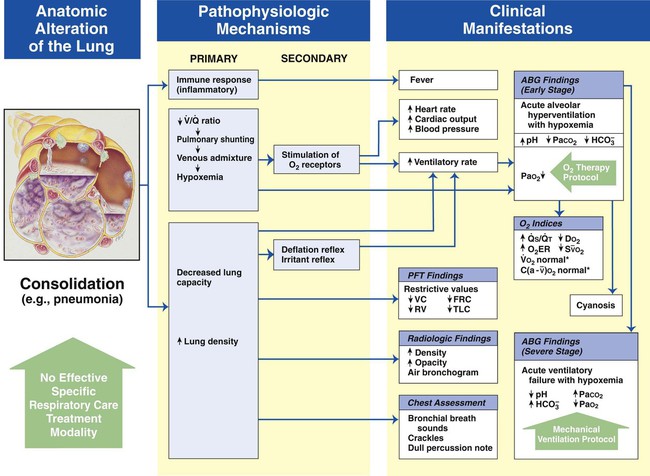

Figure 9-9 shows the pathophysiologic mechanisms caused by alveolar consolidation (e.g., pneumonia), the clinical manifestations that result, and the treatment protocols used to offset them. The hypoxemia that develops as a result of consolidation is caused by capillary shunting. This type of hypoxemia is often refractory to oxygen therapy.

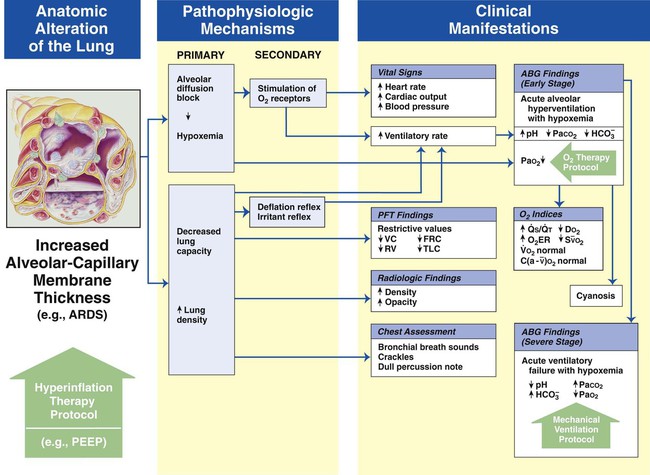

Increased Alveolar-Capillary Membrane Thickness

Figure 9-10 illustrates the major pathophysiologic mechanisms caused by increased alveolar-capillary membrane thickness (e.g., postoperative ARDS, pulmonary edema, asbestosis, chronic interstitial lung disease), the clinical manifestations that develop, and the treatment protocols used to offset them. The hypoxemia that develops as a result of an increased alveolar-capillary membrane thickness is caused by an alveolar diffusion block. This type of hypoxemia often responds favorably to oxygen therapy.

Bronchospasm

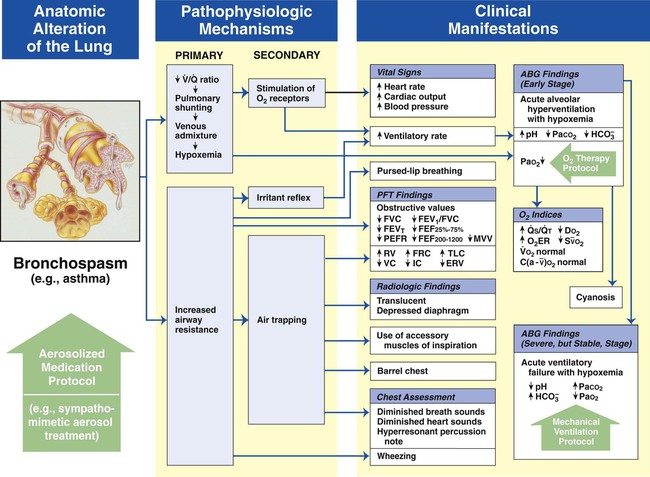

Figure 9-11 shows the major pathophysiologic mechanisms activated by bronchospasm (e.g., asthma), the clinical manifestations that result, and the appropriate treatment protocols used to offset them. The Aerosolized Medication Therapy Protocol (Bronchodilator Therapy) is the primary treatment modality used to offset the anatomic alterations of bronchospasm (the original cause of the pathophysiologic chain of events). The Oxygen Therapy Protocol and Mechanical Ventilation Protocol are secondary treatment modalities used to offset the mild, moderate, or severe clinical manifestations associated with bronchospasm. In other words, when the patient responds favorably to the Aerosolized Medication Therapy Protocol, the need for the Oxygen Therapy Protocol may be minimal and the Mechanical Ventilation Protocol may not be necessary at all.

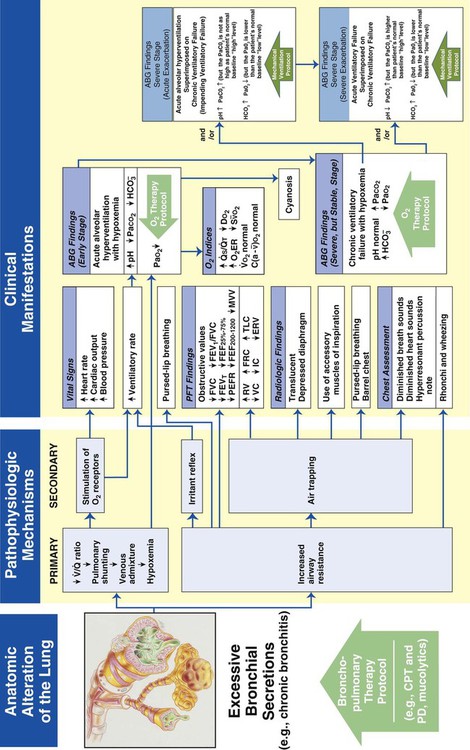

Excessive Bronchial Secretions

Figure 9-12 illustrates the major pathophysiologic mechanisms caused by excessive bronchial secretions (e.g., chronic bronchitis, asthma), the clinical manifestations that result, and the appropriate treatment protocols used to correct them. The Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol is the primary treatment modality used to offset the anatomic alterations associated with excessive bronchial secretions. When the patient demonstrates chronic ventilatory failure during the advanced stages of respiratory disorders associated with chronic excessive airway secretions (e.g., chronic bronchitis), caution must be taken not to overoxygenate the patient.

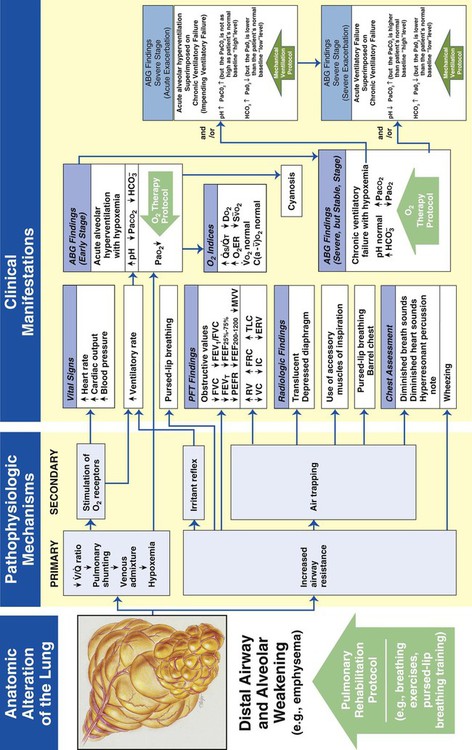

Distal Airway and Alveolar Weakening

Figure 9-13 illustrates the major pathophysiologic mechanisms caused by distal airway and alveolar weakening (e.g., emphysema), the clinical manifestations that result, and the appropriate treatment protocols used to offset them. Pulmonary rehabilitation and oxygen therapy may be all the practitioner can provide to treat the symptoms associated with distal airway and alveolar weakening. When the patient demonstrates chronic ventilatory failure during the advanced stages of the disorder, caution must be taken with the Oxygen Therapy Protocol not to over-oxygenate the patient.

Overview of Common Anatomic Alterations Associated with Respiratory Disorders

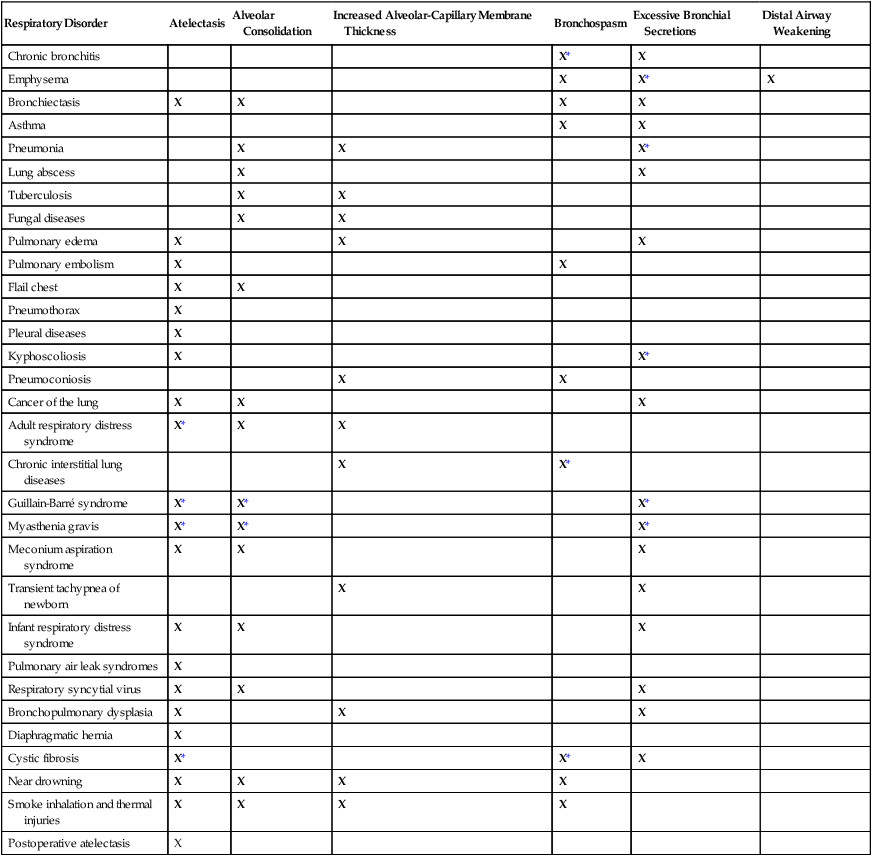

When the respiratory therapy practitioner knows and understands the chain of events (clinical scenarios) that develop in response to common anatomic alterations of the lungs, an assessment and an appropriate treatment protocol can be easily determined. Table 9-5 provides an overview of the most common anatomic alterations associated with the respiratory disorders presented in this textbook.

TABLE 9-5

Common Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs Associated With Respiratory Disorders

| Respiratory Disorder | Atelectasis | Alveolar Consolidation | Increased Alveolar-Capillary Membrane Thickness | Bronchospasm | Excessive Bronchial Secretions | Distal Airway Weakening |

| Chronic bronchitis | X* | X | ||||

| Emphysema | X | X* | X | |||

| Bronchiectasis | X | X | X | X | ||

| Asthma | X | X | ||||

| Pneumonia | X | X | X* | |||

| Lung abscess | X | X | ||||

| Tuberculosis | X | X | ||||

| Fungal diseases | X | X | ||||

| Pulmonary edema | X | X | X | |||

| Pulmonary embolism | X | X | ||||

| Flail chest | X | X | ||||

| Pneumothorax | X | |||||

| Pleural diseases | X | |||||

| Kyphoscoliosis | X | X* | ||||

| Pneumoconiosis | X | X | ||||

| Cancer of the lung | X | X | X | |||

| Adult respiratory distress syndrome | X* | X | X | |||

| Chronic interstitial lung diseases | X | X* | ||||

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | X* | X* | X* | |||

| Myasthenia gravis | X* | X* | X* | |||

| Meconium aspiration syndrome | X | X | X | |||

| Transient tachypnea of newborn | X | X | ||||

| Infant respiratory distress syndrome | X | X | X | |||

| Pulmonary air leak syndromes | X | |||||

| Respiratory syncytial virus | X | X | X | |||

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | X | X | X | |||

| Diaphragmatic hernia | X | |||||

| Cystic fibrosis | X* | X* | X | |||

| Near drowning | X | X | X | X | ||

| Smoke inhalation and thermal injuries | X | X | X | X | ||

| Postoperative atelectasis | X |

*Common secondary anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with this disorder.

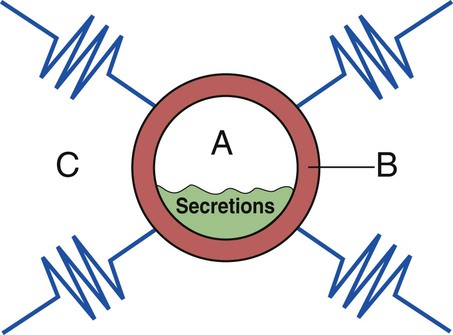

Figure 9-14 provides a three-component overview model of a prototype airway to further enhance the reader’s visualization of anatomic alterations of the lungs commonly associated with the obstructive respiratory disorders (e.g., asthma, bronchitis, or emphysema) and the treatment plans commonly used to offset them.

*The AARC Protocol Implementation Committee has developed a slide presentation of the complete survey, which is intended to assist in understanding the barriers and developing successful strategies to implement protocols (www.aarc.org; search for AARC Protocol Implementation Committee).

*See www.aarc.org/ Search Clinical Practice Guidelines for the most recent and complete list of Clinical Practice Guidelines.

*We would like to thank the Respiratory Care Department at the Kettering Medical Center, in Dayton, Ohio, for providing their Ventilator Management Protocol and Ventilator Weaning Protocol.

*See Hicks JL, O’Laughlin DT: Concept of operations for triage of mechanical ventilation in an epidemic, Acad Emerg Med 13: 223, 2006.

*The Case Study Discussion Section at the end of each respiratory disease chapter often refers the reader back to these clinical scenarios, correlating various clinical manifestations to specific pathophysiologic mechanisms and alterations of the lungs.

41, and Pa

41, and Pa

) ratio

) ratio