CHAPTER 42 The Surgical Management of Cerebellopontine Angle Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

Meningiomas comprise up to 15% of adult intracranial tumors. These tumors, usually benign and slow-growing, may affect various anatomic structures in the posterior fossa and specifically the cerebellopontine angle. The term cerebellopontine angle (CPA) meningioma has been used widely to describe meningiomas that share a common location, that is, occupancy of the CPA, although these tumors may have diverse origins with regard to the site of dural attachment, which can be outside the CPA.1

The first report of a tumor that would now be classed as a CPA meningioma was by Rokitansky2 in 1856. Virchow3 later described a psammoma originating from the posterior lip of the acoustic meatus. In 1928, Cushing and Eisenhardt4 reported on seven patients with meningiomas “simulating acoustic neuromas,” emphasizing the high surgical risk in dealing with these tumors. Several surgical series of posterior fossa meningiomas involving the CPA have been reported since then. Microsurgical series were reported by Yasargil,5 Sekhar and Janetta,6 Ojemann,7 Al-Mefty,8 Haddad and al-Mefty,9 Harrison and al-Mefty,10 Matthies and colleagues,11 Samii and Ammirati,12 and Samii and colleagues.13,14

SURGICAL PROCEDURE

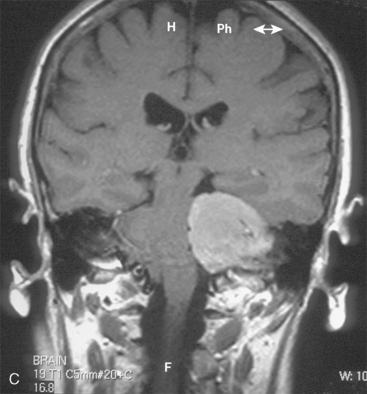

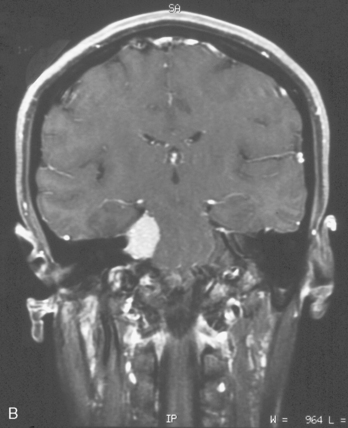

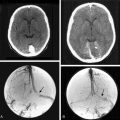

CPA meningiomas may arise from any area of the dura on the posterior surface of the petrous bone (Fig. 42-1A–C). Four general categories of tumor are found, depending on where they arise and their relationship to the VIIth and VIIIth nerve complex:

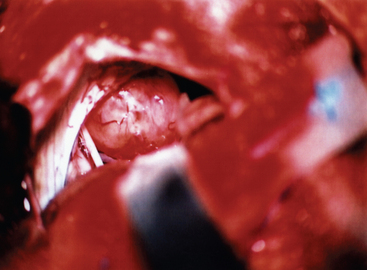

At this stage, the operating microscope is introduced into the surgical field. Great care should be taken to preserve the arachnoid planes during the dissection, as this helps to protect the adjacent cerebellum and cranial nerves. The margins of the tumor are identified, and the tumor margins are dissected away from the adjacent cerebellum and vascular and neural structures, with care being taken to preserve the arachnoid. Any feeding vessels are coagulated and divided, but great care must be taken to preserve all vascular and neural structures that may be densely adherent to the tumor capsule (Fig. 42-2).

Other approaches that have been used include the presigmoid cranial skull-base exposures.15–21 The presigmoid retrolabyrinthine craniotomy provides only a very restricted angle of approach, and is usually reserved for petroclival tumors or those lying primarily anteriorly to the pons and the mid brain. It is usually used in conjunction with a middle fossa approach with division of the superior petrosal sinus and tentorium to allow adequate access. It is only rarely necessary to use this approach in a true cerebellopontine tumor. The translabyrinthine approach gives good access to the CPA, but hearing is sacrificed. It has the major advantage of minimizing cerebellar retraction, but the access is much more restricted than with the retrosigmoid exposures, and it is difficult to remove tumors with origins extending below the lower cranial nerves. The transcochlear approach is reserved for tumors lying primarily anterior to the brain stem, and that necessitates rerouting of the facial nerve. It is only very rarely used for tumors extending into the CPA.

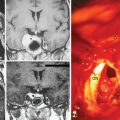

The clinical presentation of these intracanicular tumors with cranial nerve symptoms such as acoustic (tinnitus and hypacusis), vestibular (dizziness), and facial (paresis or spasm) symptoms later on is very similar to that of vestibular schwannoma, but facial nerve symptoms seem to be more common. A radiologic differentiation from vestibular schwannoma is not always possible. Some intrameatal meningiomas show broad attachment and sometimes a dural tail at the porus. Other radiologic features, such as bone invasion or invasion of middle ear structures, are more frequent in meningiomas. Surgical removal of intrameatal meningiomas should aim at wide excision, including involved dura, to prevent recurrences. The variation in the anatomy of the faciocochlear nerve bundle in relation to the tumor has to be kept in mind, and preservation of these structures should be the goal in every case. Functional preservation of the facial nerve may be achieved at similar rates as that for intrameatal schwannomas, whereas vestibular and auditory functional outcome for the most part will be superior in intrameatal meningiomas.22

COMPLICATIONS AND NUANCES

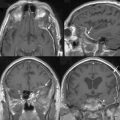

Samii and colleagues23 have shown that the clinical presentation and outcome differ between CPA meningiomas lying anterior or posterior to the IAC.

In our most recent microsurgical series of more than 100 cases House–Brackman grade 1 and 2, facial nerve function could be preserved in the great majority of patients and with much better results for tumors arising posterior to the IAC. Schaller and colleagues24 reported on 6 of 10 patients with normal preoperative facial nerve function retaining House–Brackman grade 1 to 2 after surgery by use of the retrosigmoidal suboccipital approach. Voss and colleagues25 reported 306 facial nerve dysfunction in their series of 40 patients with CPA meningiomas operated on via different approaches. The overall possibility of hearing preservation is far superior for CPA meningioma compared with vestibular schwannomas.

Tumor location seems to affect the clinical outcome in surgery of CPA meningiomas. Schaller and colleagues24 reported that postoperative outcome of facial nerve function was substantially worse in premeatal than in retromeatal tumors. Voss and colleagues25 reported in their series that facial nerve paresis occurred postoperatively in 60% of tumors arising anterior to the IAC, in 50% of tumors arising inferior to the IAC, and in fewer than 15% of tumors arising either posteriorly or superiorly. Batra and colleagues26 emphasized that all 10 patients with retromeatal tumors had House–Brackman grade 1 facial nerve function preoperatively and that all of these patients retained grade 1 function after surgery.

CSF leak after CPA tumor surgery remains a fairly common reported complication. Rates of CSF leak range from 2% to 21.9% although we have had no leak in our last 100 patients with CPA meningiomas in whom we used a retrosigmoid approach. In a recent meta-analysis of CSF leak after vestibular schwannoma surgery, Selesnick and colleagues27 found an average rate of greater than 10% across 25 reported series (total of 5964 patients). This meta-analysis also found that varied prophylactic measures, including lumbar drainage, fibrin glue, hydroxyapatite cement, bone wax, abdominal fat graft, fascia, and ionomeric cement, did not significantly reduce the CSF leak rate below the average for the grouped data. The rates of leaks among translabyrinthine, retrosigmoid, and middle fossa approaches were statistically equal. Leaks via the eustachian tube into the nasopharynx were slightly more common than incisional leaks. Although most reported series focus exclusively on vestibular schwannoma surgery, the approaches used for various CPA tumors have similar issues contributing to CSF leak.

[1] De Monte F., Marmour E., Al-Mefty O. Meningiomas. In: Kaye A.H., Laws E., editors. Brain Tumours. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2001:720-750.

[2] Rokitansky C. Lehrbuch der pathologischen Anatomie. Vienna: Wilhelm Braumüller, 1856.

[3] Virchow R.L. Die krankhaften Geschwülste: Dreissig Vorlesungen gehalten während des Wintersemesters 1862–1863 an der Universität zu Berlin. Berlin: A. Hirschwald, 1863.

[4] Cushing H., Eisenhardt L. Meningiomas: Their Classification, Regional Behaviour, Life History and Surgical End Results. New York: Hafner, 1962.

[5] Yasargil M.G., Mortara R.W., Curcic M. Meningiomas of the Basal Posterior Cranial Fossa. Vienna: Springer, 1980.

[6] Sekhar L.N., Jannetta P.J. Cerebellopontine angle meningiomas: microsurgical excision and follow-up results. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:500-505.

[7] Ojemann R.G. Meningiomas: clinical features and surgical management. In: Wilkins R.H., Rengachary S.S., editors. Neurosurgery. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1985:648-651.

[8] Al-Mefty O., Fox J.L., Smith R.R. Petrosal approach for petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:510-517.

[9] Haddad G.F., al-Mefty O. The road less traveled: Transtemporal access to the CPA. Clin Neurosurg. 1994;41:150-167.

[10] Harrison M.J., al-Mefty O. Tentorial meningiomas. Clin Neurosurg. 1997;44:451-466.

[11] Matthies C., Carvalho G., Tatagiba M., Lima M., Samii M. Meningiomas of the cerebellopontine angle. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 1996;65:86-91.

[12] Samii M., Ammirati M. Cerebellopontine angle meningioma. In: Al-Mefty O., editor. Meningiomas. New York: Raven Press; 1991:503-515.

[13] Samii M., Ammirati M. Posterior pyramid meningiomas (cerebellopontine angle meningioma). In: Samii M., Ammirati M., editors. Surgery of Skull-base Meningioma. Berlin: Springer; 1992:73-85.

[14] Samii M., Tatagiba M., Carvalho G.A. Retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach to Meckel’s cave and the middle fossa: Surgical technique and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:235-241.

[15] Arnautovic K.I., Al-Mefty O. Cerebellopontine angle meningiomas. In: Kaye A.H., Black P., editors. Operative Neurosurgery. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:545-557.

[16] Arriaga M., Brackmann D., Hitselberger W. Extended middle fossa resection of petroclival and cavernous sinus neoplasms. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:693-698.

[17] Daspit C.P., Spetzler R., Pappas C. Combined approach for lesions involving the cerebellopontine angle and skull base: experience with 20 cases—preliminary report. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;105:788-796.

[18] Hitselberger W.E., House W.F. A combined approach to the cerebellopontine angle. Arch Otolaryngol. 1966;84:267-285.

[19] Kawase T., Shibora R., Toya S. Anterior transpetrosal-transtentorial approach for sphenopetroclival meningiomas. Surgical method and results in 10 patients. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:869-876.

[20] Morrison A.W., King T.T. Experiences with a translabyrinthine transtentorial approach to the cerebellopontine angle. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1973;38:382-390.

[21] Sakaki S., Takeda S., Fujita H., et al. An extended middle fossa approach combined with a suboccipital craniectomy to the base of the skull in the posterior fossa. Surg Neurol. 1987;28:245-252.

[22] Nakamura M., Roser F., Mirzai S., Matthies C., Vorkapic P., Samii M. Meningiomas of the internal auditory canal. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(1):119-127. discussion 127–8

[23] Samii M., Turel K.E., Penkert G. Management of seventh and eighth nerve involvement by cerebellopontine angle tumors. Clin Neurosurg. 1985;32:242-272.

[24] Schaller B., Heilbronner R., Pfaltz C.R., Probst R.R., Gratzl O. Preoperative and postoperative auditory and facial nerve function in cerebellopontine angle meningiomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;112:228-234.

[25] Voss N.F., Vrionis F.D., Heilman C.B., Robertson J.H. Meningiomas of the cerebellopontine angle. Surg Neurol. 2000;53:439-446.

[26] Batra P.S., Dutra J.C., Wiet R.J. Auditory and facial nerve function following surgery for cerebellopontine angle meningiomas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:369-374.

[27] Selesnick S.H., Liu J.C., Jen A., Newman J. The incidence of cerebrospinal fluid leak after vestibular schwannoma surgery. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:387-393.