Chapter 66 The Stability-Conservative Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Rehabilitation Protocol

Introduction

It is based on the following premises and principles:

History

Until the late 1980s, ACL rehabilitation was rendered cautiously on the theory that stability was fragile and strain in the graft needed to be minimized in the early postoperative period to avoid loss of stability. It was well known that grafts lose much of their tensile strength in the first few postoperative months.1–3 It was recognized that grafts require time to heal into bone tunnels before which they are subject to loosening2,4 (see Chapter 56). Finally, it was also known that quadriceps contractions in the terminal 50 degrees of extension exerted a powerful anterior translational moment on the tibia that strains the ACL.5,6 As bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) grafts became popular during the 1980s, it became apparent that many knees became stiff and had prolonged quadriceps weakness. This stiffness was potentially a worse problem than the laxity of ACL deficiency. A stable but stiff knee was more likely to be worse than an unstable knee. In 1990 Shelbourne published his classic paper7 introducing accelerated rehabilitation. This challenged the then-accepted view that grafts needed to be carefully protected during the first few postoperative months. He stated that his patients who were somewhat noncompliant with his postoperative restrictions and were more active had no greater incidence of instability than the compliant patients. However, these more active patients had less stiffness and weakness. He postulated that “accelerated” early aggressive rehabilitation was thus not harmful and also necessary to ensure restoration of motion and strength. Based on these observations he developed his accelerated rehabilitation protocol, which is currently used in some form by most ACL surgeons.

Symmetric Stability After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction is Not Assured

Many surgeons commonly use exercises such as cycling and squats that cause quadriceps contractions in the terminal 50 degrees of extension in the early postoperative period. As shown by the research of Beynnon and others8,9 (see Chapter 64), these activities exert a significant strain on the ACL. The accelerated rehabilitation protocol states that stability will not be compromised by such ACL-straining activities if the surgery is properly performed. Yet, as shown in the most recent meta-analysis10 to review all such papers and as discussed elsewhere in this book (see Chapter 69), symmetrical stability after ACLR is currently achieved in only about half of all reconstructed knees, even in the hands of the very experienced ACL surgeons. Accelerated rehabilitation was developed, in particular, to overcome stiffness and weakness in BPTB patients. However, mean KT-1000 scores for BPTB from the literature showed that 34% of reconstructed knees had more than 2 mm of increased laxity than the normal knee, the stability level usually seen with a partially torn ACL. Of the 66% that were within 2 mm, it is estimated that one-fourth or 17% had exactly 2 mm of increased laxity. Thus 34% + 17% or 51% in all had 2 mm or more increased laxity. This leaves only about half with restoration of stability that is the same as the opposite knee. In addition, 5.9%, or roughly 1 in every 17 knees, had abnormal stability (i.e., a failed graft). Thus some of the most experienced knee surgeons in the world in the current literature are only restoring even approximately symmetrical stability—within 1 mm of the other knee—to half of the operated BPTB knees. Half have stability at a level seen with a partially torn ACL or worse.

Why Protect The Graft in The First 3 Months Postoperatively?

Fixation Point Healing

The studies of Milano and others,2 which are discussed in Chapter 56, show that soft tissue healing into tunnels can take 2 months or longer. During this time, strain on the graft has the potential to make the fixation slip and the graft lax. This healing occurs several weeks earlier in BPTB grafts than in soft tissue grafts.

Muscular Inhibition After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Effusions,11–13 ACL injury,14,15 and knee pain16,17 have all been shown to have an inhibitory effect on knee musculature, especially the quadriceps, apparently through afferent inhibition of motor neuron activity. This means that during roughly the first 3 postoperative weeks, when most patients have a large hematoma and some knee pain, it may be difficult or impossible to generate large-enough muscle contractions to strengthen or effectively prevent atrophy. In the past when we attempted to begin strengthening immediately after surgery, we noticed that strength gains did not occur, probably for this reason. In addition, the exercises produced significant patient discomfort. For this reason we no longer begin strengthening until roughly the end of the third postoperative week for isometric quadriceps and later for other muscle groups in which atrophy is less of a concern.

Cyclical Loading Does Cause Laxity

Every study that has looked at this subject has shown that cyclical loading induces elongation of the graft–fixation construct. These studies typically show several millimeters of elongation.18–20 The best such study showed 1 mm after the first 100 cycles. Many of these studies look only at the first 1000 cycles.18 One thousand cycles is equal to the number of steps taken in less than 1 week of normal activity and less than 1 week of cycling during rehabilitation. It is highly likely that this elongation would further increase if more cycles were performed. It is important to realize that only 2 mm of elongation from cyclical loading is enough to change the side-to-side difference from –1 mm to –3 mm, converting good stability to the stability level seen in a partial ACL tear.

Why Avoid Hyperextension?

The studies of Beynnon (see Chapter 64) have shown that hyperextension strains the graft significantly. Thus hyperextension should be avoided for that reason. Also, hyperextension is not used during normal gait. In our large long-term study21 of patients after hamstring (HS) ACLR, patients were told to avoid hyperextension for the first year after surgery. At follow-up (as long as 8 years postoperatively) most patients had recovered symmetrical hyperextension. All patients had essentially full extension. No patient experienced any clinical motion deficit. Thus nothing was lost by avoiding hyperextension in our rehabilitation protocol, and we believe a potential stability benefit was obtained by avoiding the strain that hyperextension would have exerted on the graft. Others have thought that achieving full hyperextension is necessary to achieve full painless motion. We have not found this to be the case with our patients. We should point out, however, that our experience is limited to soft tissue grafts. It is possible that hyperextension may provide some benefit for BPTB grafts that it does not for HS grafts.

Why Insist on Full Extension and How to Achieve it

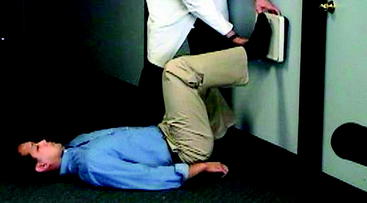

Full extension is necessary to avoid walking on a flexed knee. During full extension the quadriceps is lax, thus diminishing tension on the patellar tendon and avoiding compressive force on the patella. If full extension is not achieved, causing the patient to walk on a flexed knee, there is greatly increased patellar tendon tension and patellofemoral compressive force. Either or both of these phenomena can produce pain from patellar tendonitis or patellar chondromalacia, respectively. Thus obtaining full extension is the single most important aspect of ACL rehabilitation because it allows painless walking. We obtain full extension via an extensional force applied to the supine patient’s proximal tibia from the physical therapist and/or the patient’s family members, as well as various stretching exercises. We do not use or allow quadriceps contractions to help achieve it because quadriceps contractions in terminal extension result in a powerful strain on the ACL (Fig. 66-1).

Why Avoid Full Flexion?

Flexion of 110 degrees is necessary to descend stairs. We work to achieve flexion of 115 to 120 degrees to provide a flexion reserve in this regard. However, we avoid hyperflexion in the first 6 months because it increases strain in the graft6 and serves no functional purpose. Again, our long-term follow-up study showed that patients almost always regained full extension on their own after their discharge at a later time, when the graft was able to withstand the powerful strain thus induced.

Quadriceps Strengthening

Quadriceps contraction, whether open or closed chain (see Chapter 64), strains the ACL significantly from 0 to roughly 50 degrees of flexion depending on the study.22,23 Contrary to prior thought, Beynnon (see Chapter 64) has shown that this strain is not decreased in closed chain exercises relative to open chain. We do not begin quadriceps strengthening until 110 degrees of knee flexion is obtained because strengthening of a muscle can decrease its elasticity and thus could inhibit attempts to achieve flexion. However, when 110 degrees of flexion is achieved (usually by the end of the second week), we believe it is safe to begin protected quadriceps strengthening. To avoid cyclical loading we use an isometric exercise called the “wall push” (Fig. 66-2). This produces an isometric quadriceps contraction with the knee flexed 90 degrees. This 90-degree mark is easy for patients to remember when doing the exercise on their own. Patients lie on their back on the floor and flex the hips and knees to 90 degrees, putting the flat foot on the wall. A family member or friend holds a bathroom scale between the foot and the wall to record the compressive pressure achieved. This can be charted at home to mark the progression of strength and gives the patient a goal to achieve and exceed as strength increases. Only the operated extremity is strengthened to promote symmetry between the legs. This exercise has the benefit of being able to be done entirely at home, without clinic visits, once the exercise has been properly demonstrated to the patient.

Lower Extremity Cyclical Loading

Cycling, Running, and Elliptical Training

There is no lower extremity cyclical loading exercise that does not strain the ACL. Graft abrasion can also occur before full tunnel healing has occurred. We therefore view this as the highest-risk part of the rehabilitation protocol and delay it until the fourth postoperative month, when all fixation points should be well healed. Grafts are still weak and still remodeling at this time but should be much better able to withstand strain and tunnel abrasion than in the earlier postoperative period. We begin with elliptical training (Fig. 66-3) and cycling in month 4. We allow running in month 5. We delay the onset of running because it is more likely than cycling and elliptical training to cause patellofemoral symptoms. If tendonitis or patellar symptoms start, we stop these exercises for a week or two and begin again. Freestyle swimming can also be started at this time.

Hamstring Versus Bone–Patellar Tendon–bone

Our experience with this protocol is limited to the use of HS grafts because we do not perform patellar tendon grafts. It is possible that it is less suited for BPTB grafts due to their greater tendency toward stiffness and quadriceps atrophy. Also, the more rapid healing of the bone plug in the tunnel may decrease the risk of some of the features of the accelerated program. Even if the accelerated program were to decrease BPTB stability, it might be justified to avoid greater problems with motion and atrophy. We think that studies comparing somewhat less accelerated protocols after BPTB would be useful in this regard. We would also suggest that those using the accelerated program review Dr. Shelbourne’s excellent chapter reviewing it in this text (see Chapter 65). We believe the protections he provides, especially in the first postoperative week, are not clearly known to many and bear reviewing.

Allograft Rehabilitation

Allografts are associated with lower stability rates (see Chapter 69) and delayed recellularization (see Chapter 55). For this reason we believe it is prudent to progress at a slightly slower rate with allografts. We have no supporting data, but we begin cyclical loading after 4 months instead of 3 and allow full activities at 9 months instead of 6.

Results

This protocol has been associated with a 0% rate of graft failure20 in both primary and revision ACLRs with no significant permanent motion problems. Complete restoration of strength by 6 months postoperatively has been routinely obtained. Patients lose strength early postoperatively but generally have little difficulty getting it back. The only exceptions to this have been a small number of patients with patellar degeneration, in whom intensive quadriceps loading is avoided to avoid exacerbation of their symptoms.

Summary of Protocol

1 Blickenstaff KR, Grana WA, Egle D. Analysis of a semitendinosus autograft in a rabbit model. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:554-559.

2 Milano G, Mulas PD, Sanna-Passino E, et al. Evaluation of bone plug and soft tissue anterior cruciate ligament graft fixation over time using transverse femoral fixation in a sheep model. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:532-539.

3 Weiler A, Peters G, Maurer J, et al. Biomechanical properties and vascularity of an anterior cruciate ligament graft can be predicted by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:751-761.

4 Rodeo SA, Arnoczky SP, Torzilli PA, et al. Tendon-healing in a bone tunnel: a biomechanical and histological study in the dog. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75A:1795-1803.

5 Beynnon BD, Fleming BC, Johnson RJ, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament strain behavior during rehabilitation exercises in vivo. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:24-34.

6 Beynnon BD, Howe JG, Pope MH, et al. The measurement of anterior cruciate ligament strain in vivo. Int Orthop. 1992;16:1-12.

7 Shelbourne KD, Nitz P. Accelerated rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18:292-299.

8 Fleming BC, Beynnon BD, Renstrom PA, et al. The strain behavior of the anterior cruciate ligament during bicycling: an in vivo study. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:109-118.

9 Markolf KL, O’Neill G, Jackson SR. Effects of applied quadriceps and hamstrings muscle loads on forces in the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1144-1149.

10 Prodromos CC, Joyce BT, Shi K, et al. A meta-analysis of stability after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction as a function of hamstring versus patellar-tendon graft and fixation type. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1202-1208.

11 DeAndrade JR, Grant C, Dixon AS. Joint distension and reflex muscle inhibition in the knee. J Bone Joint Surg. 1966;47A:313-322.

12 Fahrer H, Rentsch HU, Gerber NJ, et al. Knee effusion and reflex inhibition of the quadriceps. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70B:635-638.

13 Jones DW, Jones DA, Newham DJ. Chronic knee effusion and aspiration: the effect on quadriceps inhibition. Br J Rheumat. 1987;26:370-374.

14 Konishi Y, Suzuki Y, Hirose N, et al. Effects of lidocaine into knee on QF strength and EMG in patients with ACL lesion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1805-1808.

15 Konishi Y, Fukubayashi T, Takeshita D. Possible mechanism of quadriceps femoris weakness in patients with ruptured anterior cruciate ligament. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:1414-1418.

16 Morrissey MC. Reflex inhibition of thigh muscles in knee injury: causes and treatment. Sports Med. 1989;7:263-276.

17 Stokes M, Young A. The contribution of reflex inhibition to arthrogenous muscle weakness. Clin Sci. 1984;67:7-14.

18 Coleridge SD, Amis AA. A comparison of five tibial-fixation systems in hamstring-graft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12:391-397.

19 Kousa P, Jarvinen TLN, Vihavainen M, et al. The fixation strength of six hamstring tendon graft fixation devices in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Part II: tibial site. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:182-188.

20 Giurea M, Zorilla P, Amis AA, et al. Comparative pull-out and cyclic-loading strength tests of anchorage of hamstring tendon grafts in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:621-625.

21 Prodromos CC, Han YS, Keller BL, et al. Stability results of hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction at two- to eight-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:138-146.

22 Renstrom P, Arms SW, Stanwyck TS, et al. Strain within the anterior cruciate ligament during hamstring and quadriceps activity. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14:83-87.

23 Durselen L, Claes L, Kiefer H. The influence of muscle forces and external loads on cruciate ligament strain. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:129-136.