Chapter 65 Principles of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rehabilitation

Introduction

The main complication after ACL reconstruction has been the limitation of knee range of motion or arthrofibrosis. Arthrofibrosis is defined as abnormal proliferation of fibrous tissue in and around a joint that can lead to loss of motion, pain, and muscle weakness. It is believed that arthrofibrosis is more common with the patellar tendon autograft, but it is found with all graft sources.1–4 We believe that improper perioperative rehabilitation, not the graft source itself, is the culprit for causing arthrofibrosis and that it can be avoided with all ACL reconstruction surgery if the proper rehabilitation is applied before and after surgery.

People have symmetrical knees that are unique to the individual. In evaluating full range of motion, an important consideration is that 99% of women and 95% of men show some degree of hyperextension in their knees with averages of 5 and 6 degrees, respectively.5 Current data analysis of results of ACL reconstruction shows that any loss of knee extension or flexion is the major factor related to lower subjective scores at 10 to 20 years after surgery. Even the loss of 3 to 5 degrees of extension compared with the opposite knee can result in lower postoperative subjective scores.6 Thus the definition of full range of motion must depend on symmetry between the knees rather than the conventional practice of gauging knee motion against a fixed standard.

To measure knee extension, the heel of the foot should be placed on a bolster so that the knee can fall into hyperextension (Fig. 65-1). The motion should be compared with the opposite normal knee. To get a kinetic feel for how easily the knee moves into hyperextension, the examiner can evaluate hyperextension by placing one hand above the knee to fix the femur and placing the other hand on the patient’s foot to lift the heel off the table (Fig. 65-2). Knee flexion can be measured by having the patient pull the heels toward the buttocks. When the knee is normal, the patient can kneel and sit back on the heels comfortably (Fig. 65-3). These evaluation tools should be used to determine whether the patient has full symmetrical knee motion.

Preoperative Rehabilitation

The initial emphasis after an acute injury to the ACL is to control and then decrease the amount of swelling and pain. We use the knee Cryo/Cuff (Aircast, Summit, NJ), which combines cold with compression to reduce the hemarthrosis. The second goal of rehabilitation after an acute ACL injury is to restore normal knee range of motion, including full hyperextension equal to the noninjured knee. Obtaining full range of motion before surgery reduces the likelihood of motion problems postoperatively.7–9

A habit of performing full hyperextension exercises is important to develop preoperatively so that the exercises are easily a part of a daily routine after surgery. Several exercises and modalities are used to gain full normal hyperextension. Towel stretches are performed as a passive self-mobilization technique using a towel looped around the midfoot. The towel ends are held in one hand while the other hand is used to press and hold the thigh to the table. The towel is used to lift the heel of the affected lower extremity to end-range hyperextension by pulling the end of the towel upward toward the shoulder, where it is held for a count of 5 seconds, and then the heel is lowered back to the table (Fig. 65-4). For patients who have decreased quadriceps muscle control, an active heel-lift exercise can easily be added to the towel stretch. The active heel lift is accomplished by contracting the quadriceps musculature after the towel stretch is performed, trying to keep the heel of the affected leg elevated without using the towel to hold it in the air. Initially after injury, patients often display some degree of quadriceps muscle inhibition, making a normal gait pattern difficult. It is important that the patient continue to try to actively elevate the heel to the height of the passive stretch.

Mental Preparation

The second important factor in the preoperative preparation of an ACL reconstruction procedure is the mental preparation of the patient. Physical therapists follow patients closely and communicate with the surgeon regarding a patient’s mental and physical preparation for surgery, as the success of reconstruction depends on both factors.10 The physician must explain the nature of the injury to the athlete and family. The patient benefits from a detailed explanation of the operative procedure and the postoperative rehabilitation. The physical therapist should also review with the patient exactly what will be performed in all phases of the postoperative rehabilitation and how each phase of rehabilitation will be accomplished. The patient should approach the reconstruction procedure with a positive mental outlook. A “let’s just get it over with” attitude is not acceptable and can lead to less than superior results, even with perfect surgical and rehabilitation techniques. The patient should arrive in the operating room ready to go with an attitude of looking forward to the reconstructive procedure and with an understanding of the postoperative rehabilitation.

Postoperative Rehabilitation

Ipsilateral or Contralateral Graft

Rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction involves two different rehabilitation efforts with different goals. First is the rehabilitation of the knee as it pertains to the placement of the ACL graft intraarticularly. Second is the rehabilitation of the graft donor site. To do both effectively in the same knee, one rehabilitation effort must take precedence over the other to prevent the main complication of arthrofibrosis in the knee. Of utmost importance for the ACL graft in the short and long term is achieving full knee range of motion equal to the normal knee. This includes full hyperextension and the patient’s ability to kneel and sit back on his or her heels, as shown in Figs. 65-1 to 65-3. To rehabilitate the graft donor site, repetitive stress must be applied to the patellar tendon to stimulate it to regrow in size and strength. The sooner this repetitive stress can be provided, the more one can take advantage of the inflammatory response from harvesting the middle third of the patellar tendon. These two immediate goals for the ACL graft and the graft donor site are difficult to achieve simultaneously in the same knee without causing swelling and difficulty with achieving full range of motion. Therefore when a graft is harvested from the ipsilateral knee, the goal of achieving full range of motion takes precedence over rehabilitating the graft donor site.

Our choice of whether to use an ipsilateral or a contralateral patellar tendon graft is based solely on the individual patient goals. The senior author used ipsilateral grafts for primary ACL surgery from 1982 to 1994 but used contralateral grafts during that time period for revision ACL reconstruction when patients had already had the patellar tendon graft used in their involved knees for primary reconstruction. We observed the ease of rehabilitation experienced by patients when the contralateral patellar tendon was used for revision surgery, especially with regard to the quick return of knee range of motion in the ACL reconstructed knee.10–12 Patients also reported that the ACL reconstructed knee felt normal to them very early after surgery, and they were able to return to their normal activities and sports very quickly. We initially began using the contralateral graft for primary ACL reconstruction in high-level athletes who wanted a quick return to sport. With its success and ease for achieving full symmetrical range of motion and strength, we realized that the use of the contralateral graft was appropriate for any patient.13 We currently use the contralateral graft source for about 75% of patients.

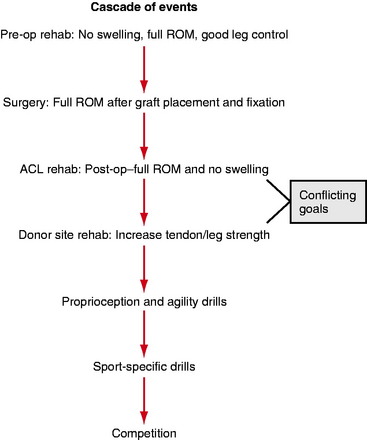

The rehabilitation program explained in this chapter can be followed regardless of the graft source or surgical technique used because the principles of rehabilitation and goals for patients are the same: to obtain knee symmetry for range of motion, strength, stability, and function. If the rehabilitation program provided follows the progression shown in Fig. 65-5, all the patient’s goals can be met.

Operative Considerations

As the patient arrives in the postoperative recovery area, the ACL reconstructed leg is placed into a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine set to move the knee from 0 to 30 degrees of flexion. CPM not only provides gentle motion, but more importantly also elevates the lower leg. The graft donor leg is also elevated on pillows to the same level to avoid increased strain on the lower back that can lead to lumbosacral pain. Both knees are elevated above the level of the heart (Fig. 65-6).

Phase I: Early Postoperative Period

We start with exercises for range of motion with assisted flexion in a CPM machine for the ACL reconstructed leg. The patient is instructed to maximally flex the CPM to 125 degrees and hold this position for a period of 3 minutes. The CPM is progressed to maximum flexion slowly and as tolerated by the patient. Heel-slide exercises are performed next for both the ACL reconstructed leg and the contralateral donor site leg. A yardstick is positioned next to the leg with the zero end aligned with the end of the heel (Fig. 65-7). The yardstick provides a visual cue for patients to easily monitor the progress of knee flexion. Next, the patient flexes the knee with the help of a towel looped under the thigh until further flexion becomes difficult. Terminal flexion is held for 1 minute. The number of centimeters the heel has traveled is recorded. This number makes it easy for the patient and physical therapist to communicate changes in range of motion over the phone during the first week when the patient is at home. Flexion in the ACL reconstructed leg should be approximately 110 to 120 degrees immediately postoperatively. Flexion in the contralateral graft donor knee should be full and equal to preoperative measurements because harvesting the graft alone does not cause swelling and the patellar tendon has been stretched to maximal length while still in the operating room.

The patient then props both legs into extension with the heels resting on the Cryo/Cuff canister, allowing for any hyperextension. A small 2.5-pound weight is placed just distal to the incision on the ACL reconstructed leg. This exercise is maintained for 10 minutes. Following the heel prop exercise, the patient performs three to five knee thunk exercises on each knee, in which the patient flexes the knee to a height of several inches and then allows the leg to relax and “thunk” into hyperextension. Thunk exercises can be difficult for patients to perform on the ACL reconstructed leg at first for fear of damaging the ACL reconstruction. Typically, therefore, thunk exercises are performed first on the graft donor leg so that the patient understands how hyperextension feels. Five to ten towel stretch exercises are performed for each leg as described previously. Active heel-lift exercises are combined with the towel stretch to achieve good quadriceps control (Fig. 65-8).

Straight leg raise exercises for leg control are performed on both legs by having the patient first initiate a quadriceps muscle contraction and then focus on maintaining the knee in a locked-out position while lifting the leg so that the heel is 2 to 3 feet in the air above the mattress (Fig. 65-9). To provide high repetition stress to the graft donor site while still remaining in bed, we use the Shuttle (Contemporary Design, Glacier, WA). The Shuttle is a light-weight, low-resistance portable leg press machine (Fig. 65-10). Resistance is provided by the placement of weighted rubber cords, each adding additional resistance. This weight is applied during both the concentric and eccentric movements. Twenty-five repetitions with one cord (7 pounds) are then completed with the emphasis on slow, controlled motion.

The drains are removed from both knees the following morning, and an identical set of exercises is performed. At the end of this session, the patient ambulates for the first time. This is accomplished carefully to avoid a fall. First, the patient sits at the edge of the bed and, when it is clear that the patient is steady and not dizzy, standing is encouraged. Standing is allowed for a few minutes, with the clinician close by to make sure a vasovagal episode does not occur. Next, the patient is instructed to shift his or her weight over to the ACL reconstructed leg and lock that leg into hyperextension with a quadriceps muscle contraction (Fig. 65-11). The patient then ambulates to the door of the room and back using small steps and focusing on a point high on the wall in the direction of ambulation. Patients are allowed to ambulate with full weight bearing as tolerated; however, the use of crutches or a walker is allowed for patients who are unsteady on their feet and are at risk of falling.

Postoperative Rehabilitation Phase II

During week 2, the CPM is discontinued while cold/compression therapy continues. The cold/compression device is used by the patient as needed throughout the day to control swelling, and continued use throughout the night is encouraged but is not required if swelling is adequately controlled. Shuttle exercises for the contralateral graft donor leg are progressed as described previously as long as the patient retains full flexion. Front step-down exercises are initiated at this point, and patients start with 50 repetitions three times per day on the 2-inch step. This is progressed in a similar manner to the Shuttle until the patient is performing 100 repetitions on the 2-inch step. The patient independently advances this progression based on the amount of donor site soreness. The step box, a hinged, foldable device, allows step exercises from heights up to 8 inches. Patients are instructed to perform front step-down exercises, focusing on quality of form and technique rather than quantity of the number performed (Fig. 65-12). Balancing on the graft donor leg with the hands placed on the hips, the patient lowers the heel of the opposite leg to the floor in front of the step box until it touches the floor. It is important for the patient to keep the pelvis in a neutral position during the descent phase to prevent compensation from the hip musculature.

Comment

Some physicians believe that patients should not be allowed to return to competitive sports until 6 months to 1 year after surgery because they believe that it takes that long for the ACL graft to mature and that graft maturation is what will prevent ACL graft rupture in the future. There is nothing magical about an arbitrary time of 6 months that makes it safe for a patient to return to sports. We have found that it takes patients 3 to 4 months of playing their sport before they feel that the knee has returned to normal. Interestingly, patients who do suffer an ACL graft rupture do so after they have been back to playing and are at the level of feeling normal, and not during the first few months of playing. We have not found a specific time after surgery where the ACL graft is most vulnerable. The average time of ACL graft tear is 2.1 years (range, 3 months–9.2 years) after surgery, and the time of graft tear is equally distributed over that time.14

1 Chang SK, Egami KD, Shaieb MD, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: allograft versus autograft. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:453-462.

2 Corry IS, Webb JM, Clingeleffer AJ, et al. Arthroscopic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. A comparison of patellar tendon autograft and four-strand hamstring tendon autograft. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:444-454.

3 Ejerhed L, Kartus J, Sernert N, et al. Patellar tendon or semitendinosus tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A prospective randomized study with a two-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:19-25.

4 Eriksson K, Anderberg P, Hamberg P, et al. A comparison of quadruple semitendinosus and patellar tendon grafts in reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg. 2001;83B:348-354.

5 DeCarlo MS, Sell KE, Shelbourne KD, et al. Current concepts on accelerated ACL rehabilitation. J Sport Rehab. 1994;3:304-318.

6 Shelbourne KD. 2005. Unpublished data

7 Mohtadi NG, Webster-Bogaert S, Fowler PJ. Limitation of motion following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A case-control study. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:620-624.

8 Shelbourne KD, Patel DV. Timing of surgery in anterior cruciate ligament-injured knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1995;3:148-156.

9 Shelbourne KD, Wilckens JH, Mollabashy A, et al. Arthrofibrosis in acute anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The effect of timing of reconstruction and rehabilitation. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:332-336.

10 Rubinstein RAJr, Shelbourne KD, VanMeter CD, et al. Isolated autogenous bone-patellar tendon-bone graft site morbidity. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:324-327.

11 Shelbourne KD, Thomas JA. Contralateral patellar tendon and the Shelbourne experience. Part 1. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and rehabilitation. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2005;13:25-31.

12 Shelbourne KD, Thomas JA. Contralateral patellar tendon and the Shelbourne experience. Part 2. Results of revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2005;13:69-72.

13 Shelbourne KD, Urch SE. Primary anterior cruciate ligament using the contralateral autogenous patellar tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:651-658.