14 The shoulder region

The mechanics of the shoulder are rather complex. The shoulder ‘joint’ in fact comprises three components – the gleno-humeral joint or shoulder joint proper, the acromio-clavicular joint, and the sterno-clavicular joint. The gleno-humeral joint allows a free range of abduction, flexion, and rotation, under the control of the scapulo-humeral and pectoral muscles. The other two joints together allow 90 ° of rotation of the scapula upon the thorax and a moderate range of antero-posterior gliding of the scapula, under the control of the cervico-scapular and thoraco-scapular muscles.

SPECIAL POINTS IN THE INVESTIGATION OF SHOULDER SYMPTOMS

Exposure

The patient must be stripped to the waist. The examination is conducted most easily with the patient standing; alternatively he may sit upon a high stool. For the greater part of the examination the surgeon stands behind the patient, so that he may observe more easily the position of the scapula.

Steps in routine examination

A suggested plan for the routine examination of the shoulder is summarised in Table 14.1.

Table 14.1 Routine clinical examination in suspected disorders of the shoulder

| 1. LOCAL EXAMINATION OF THE SHOULDER REGION | |

| Inspection | Power |

| Bone contours alignment | Cervico-scapular and thoraco-scapular muscles (controlling scapular movement)—Test elevation of scapula, retraction of scapula, abduction-rotation of scapula |

| Soft-tissue contours | |

| Colour and texture of skin | |

| Scars or sinuses | |

| Palpation | |

| Skin temperature | Scapulo-humeral muscles (controlling movement at gleno-humeral joint)—Abduction, adduction, flexion, extension, lateral rotation, medial rotation |

| Bone contours | |

| Soft-tissue contours | |

| Local tenderness | |

| Movements | Acromio-clavicular joint |

| Distinguish between true gleno-humeral movement and scapular movement during abduction, flexion, extension, lateral rotation, and medial rotation | Examine for swelling, increased warmth, tenderness, pain on movement, and stability |

| ?Pain on movement | |

| ?Muscle spasm | |

| ?Crepitation on movement | |

| Sterno-clavicular joint | |

| Examine for swelling, increased warmth, tenderness, pain on movement, and stability | |

| 2. EXAMINATION OF POTENTIAL EXTRINSIC SOURCES OF SHOULDER SYMPTOMS | |

Movements at the shoulder

In examining shoulder movements it is important to determine how much of the movement occurs at the gleno-humeral joint and how much is contributed by rotation of the scapula. An accurate distinction between the two types of movement can be made only by grasping the lower half of the scapula so that its movements can be detected (Fig. 14.1). In the normal shoulder about half the range of abduction occurs at the gleno-humeral joint and half by scapular rotation. Disorders of the shoulder generally cause restriction of gleno-humeral movement rather than of scapular movement. If the shoulder joint proper (the gleno-humeral joint) is fused, either naturally or by operation, a range of abduction of up to 60 or 80 ° is possible by scapular movement alone.

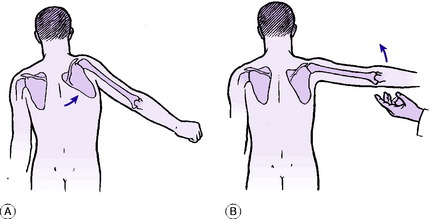

Stand behind the patient. Abduction: Instruct the patient to try to raise both arms sideways from the body so that the palms of the hands meet above the head. Measure the range, and observe what proportion of the movement takes place at the gleno-humeral joint and how much is contributed by rotation of the scapula upon the thorax. Flexion: Instruct the patient to raise the arms forwards towards the vertical. Again observe (by means of the hand upon the scapula) what proportion of the movement occurs at the gleno-humeral joint and how much is contributed by rotation of the scapula on the chest wall. Extension: Ask the patient to raise the elbows backwards. Lateral (external) rotation: The elbows are held in to the sides and are flexed 90 ° (Fig. 14.2): the forearms then serve as convenient pointers to indicate the angle of rotation (normal range = 80 °). Medial (internal) rotation: Instruct the patient to place the back of his hand in contact with his lumbar region and to carry the elbow forwards, bringing the finger tips up as high as possible between the shoulder blades (normal range = 110 °).

Estimation of muscle power

In estimating the power of the shoulder muscles two groups must be distinguished:

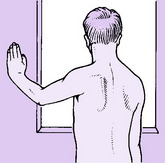

The cervico-scapular and thoraco-scapular muscles. These control movements of the scapula. Estimate the power of each group in turn and compare on the two sides. Elevators of the scapula (levator scapulae, upper fibres of trapezius): Instruct the patient to shrug the shoulders against the resistance of the examiner’s hands. Retractors of the scapula (rhomboids and middle fibres of trapezius): Instruct the patient to brace the shoulders back. Abductor-rotators of the scapula (serratus anterior, with middle and lower fibres of trapezius): Instruct the patient to push horizontally forwards with the hand against a wall (Fig. 14.3) or simply to raise the arm from the side. If the serratus anterior is weak, winging of the scapula (backward projection of its vertebral border) will be observed (Fig. 14.3).

The scapulo-humeral muscles. These control movements of the gleno-humeral joint. Estimate the power of each muscle group, testing in turn the abductors, adductors, flexors, extensors, lateral rotators, and medial rotators. If the patient has lost the power to initiate active gleno-humeral movement from the dependent position, determine whether he can maintain abduction when the limb has been raised with assistance to 90 °. Ability to sustain abduction but not to initiate it is characteristic of isolated rupture of the supraspinatus tendon (see Fig. 14.12, p. 267).

The acromio-clavicular and sterno-clavicular joints

The clavicle may be regarded as a link, jointed at each end, connecting the scapula to the sternum (Fig. 14.4). Movement of the scapula must occur about a fulcrum at one or both ends of this link. In the normal shoulder movement of the scapula, with consequent movement at the acromio-clavicular and sterno-clavicular joints, occurs mainly:

Radiographic examination

Gleno-humeral joint. The routine shoulder film is a plain antero-posterior projection with the limb in the anatomical position. When additional information is required a special axillary projection with the arm abducted 90 ° (giving a lateral view of the humerus) should be obtained. Further films showing the upper end of the humerus in varying degrees of rotation are sometimes informative. Arthrography, after injection of radio-opaque fluid into the joint, will show whether or not the capsule is intact.

Other imaging techniques

Radioisotope scanning, computerised tomography, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging must each be considered in appropriate circumstances. Double contrast arthrography combined with computerised tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be particularly valuable in demonstrating the extent of soft tissue damage in recurrent dislocation of the shoulder (see Fig. 14.10).

Extrinsic sources of shoulder and arm pain

In many cases in which the main complaint is of pain in the shoulder or arm there is no local abnormality, the symptoms being referred from a lesion elsewhere. Thus pain over the shoulder is a common symptom in affections of the neck, especially when the brachial plexus or its roots are involved. Shoulder pain is also a feature of irritative lesions in contact with the diaphragm, either in the thorax or in the abdomen. The possibility of such extrinsic lesions must always be considered in the investigation of shoulder pain.

DISORDERS OF THE SHOULDER (GLENO-HUMERAL) JOINT

PYOGENIC ARTHRITIS OF THE SHOULDER (General description of arthritis, p. 96)

Pyogenic arthritis of the shoulder is uncommon. It may complicate a penetrating wound, or it may be a haematogenous (blood borne) infection. In children infection may spread to the shoulder from a focus of osteomyelitis in the upper metaphysis of the humerus (p. 279).

The clinical features resemble those of pyogenic arthritis of other joints. The onset is rapid and is accompanied by pyrexia. The shoulder is swollen and abnormally warm, and all movements are greatly restricted. Treatment follows the lines suggested on page 98.

TUBERCULOUS ARTHRITIS OF THE SHOULDER (General description of tuberculous arthritis, p. 98)

The pathological and clinical features correspond to those of tuberculous arthritis in any major joint. Treatment with antituberculous drugs follows the general principles outlined on page 102. In early cases good recovery of function may occur, but in more advanced cases of bone and joint destruction surgical intervention with arthrodesis of the joint may be required.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS OF THE SHOULDER (General description of rheumatoid arthritis, p. 134)

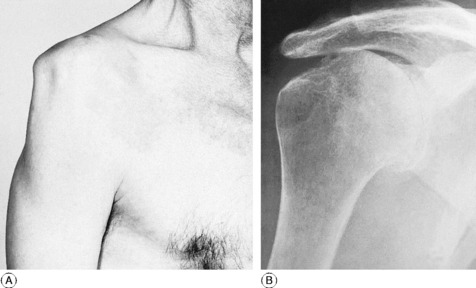

As in other superficial joints, the main clinical features are local pain and stiffness, increased warmth, swelling from synovial thickening, and marked restriction of movement. There is wasting of the deltoid muscle, with consequent flattening of the shoulder contour (Fig. 14.5A). Radiographs show rare-faction of bone, narrowing of the cartilage space, and eventually erosion of bone at the joint margins (Fig. 14.5B).

Treatment. This is mainly that for rheumatoid arthritis in general, as described on page 137. Exercises are important in maintaining a useful range of movement.

Operative treatment. Severe disability often results from the bone and cartilage destruction produced by the inflammatory rheumatoid synovitis. When this occurs replacement arthroplasty of the joint may be indicated to restore mobility and relieve pain. Early designs used a metal humeral head prosthesis with a stem cemented into the shaft of the bone (Fig. 14.6). This articulated with a small concave polyethylene prosthesis to resurface the glenoid socket. Pain relief following this surgery is usually good, but full active movement, particularly in abduction, is never restored. The main problems that compromise the result are loosening of the glenoid prosthesis because of inadequate bone support and the degeneration of the scapulo-humeral muscles. Newer prosthetic designs to address these problems, including surface replacements and reversed prostheses are under trial, but no long-term results are yet available.

OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE SHOULDER (General description of osteoarthritis, p. 140)

Clinical features. The patient is usually elderly: osteoarthritis is exceptional in the shoulders of younger patients. The main complaint is of pain in the shoulder and down the upper arm.

Radiographs show narrowing of the cartilage space: the joint outlines are clear-cut and often show some sclerosis; there is ‘spurring’ from osteophyte formation at the joint margins (Fig. 14.7).

Treatment. In most cases active treatment is unnecessary once the nature of the affection has been explained. If treatment is called for, conservative measures should usually be relied upon and gentle exercises are often helpful. If there is a large effusion it should be aspirated. Only exceptionally would operation be justified: if it were, replacement arthroplasty (see under rheumatoid arthritis, p. 260) would usually be advised, but arthrodesis might occasionally be appropriate.

‘FROZEN’ SHOULDER (Adhesive capsulitis; periarthritis)

It is important to warn the patient at the beginning that recovery may take many months, but at the same time to give assurance that eventually recovery is likely to be complete.

RECURRENT ANTERIOR DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER

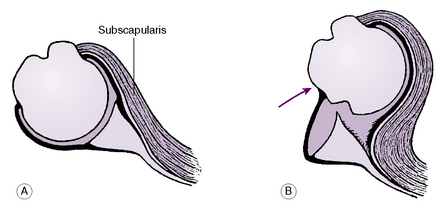

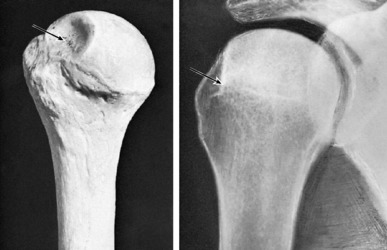

Pathology. This is twofold (Figs 14.8 and 14.9A):

Fig. 14.9 A Typical defect of articular surface of humeral head (arrow), found in most cases of recurrent dislocation of the shoulder. B Radiographic appearance with the arm in 80 ° of medial rotation. The defect (arrow) is seen in profile at the upper and outer quadrant of the humeral head.

Clinical features. The patient is usually a fit young adult, accustomed to sporting activities. Nearly always, recurrent dislocation follows an initial violent dislocation, often in a heavy fall. Thereafter dislocation recurs with trivial violence, characteristically during combined abduction, lateral rotation, and extension (for example, in putting on a coat).

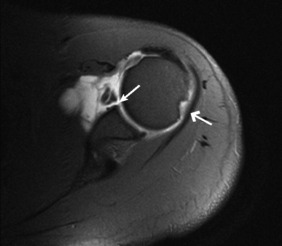

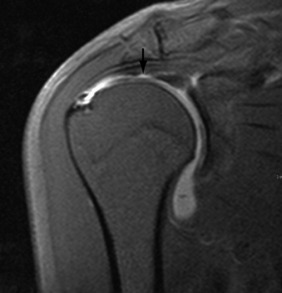

Imaging. Routine radiographs with the limb in the anatomical position do not show any abnormality, but special profile views taken with the arm in 60–80 ° of medial rotation show the characteristic bony defect of the humeral head (Fig. 14.9B). The defect is not seen in any other projection, but it can be shown more clearly by computerised tomographic (CT) imaging or by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI scan combined with arthrography provides the most detailed information on the bone and soft-tissue pathology (Fig. 14.10).

Treatment. Conservative treatment is not effective and if dislocation recurs frequently operation is justified. The two treatment principles used to prevent further dislocation are to either repair the defect in the glenoid labrum (Bankart1 operation), or to create an overlapping buttress of muscle or bone on the anterior margin of the glenoid (Putti–Platt2 or Bristow operations). Traditionally this required an open procedure through an anterior incision but increasingly this has been replaced by closed arthroscopic techniques for repair. However, it must be emphasised that the results in terms of functional outcome are identical with open or closed methods. Arthroscopic surgery, though more convenient for the patient, should only be undertaken by surgeons trained in the necessary specialist skills and equipped with the sophisticated equipment required.

RECURRENT POSTERIOR DISLOCATION

Posterior dislocation of the shoulder is much less common than anterior dislocation. Often – indeed usually – the cause is an electric shock or an epileptiform convulsion, and it is not uncommon for both shoulders to be dislocated together. The dislocation is prone to become recurrent. The pathology is analogous to that of recurrent anterior dislocation:

COMPLETE TEAR OF ROTATOR (TENDINOUS) CUFF (Torn supraspinatus)

It is important to distinguish complete tears of the rotator tendinous cuff from incomplete tears. The clinical effects are different. Whereas an incomplete tear is one cause of the ‘painful arc syndrome’ (p. 268), without obvious loss of power, a complete tear impairs seriously the ability to abduct the shoulder.

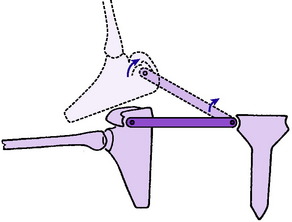

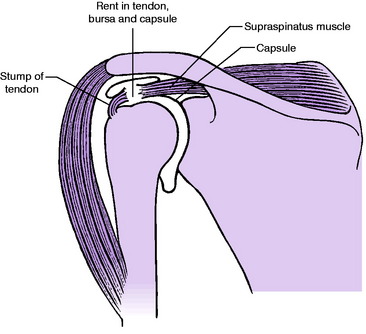

Pathology. The tear is mainly of the supraspinatus tendon, but it may extend into the adjacent subscapularis or infraspinatus tendons. The tear is close to the insertion of the tendons and usually involves the capsule of the joint, with which the tendons are blended. The edges of the rent retract, leaving a gaping eliptical hole which establishes a communication between the shoulder joint and the subacromial bursa (Fig. 14.11). In general, it may be said that a tendon that ruptures is usually already degenerate: thus rupture occurs mainly in the elderly.

Fig. 14.11 Tear of supraspinatus shown diagrammatically. Note that the subacromial bursa communicates with the shoulder joint through the rent.

On examination there is local tenderness below the lateral margin of the acromion. When the patient attempts to abduct the arm no movement occurs at the gleno-humeral joint but a range of about 45–60 ° of abduction can be achieved, entirely by scapular movement (Fig. 14.12A). There is, however, a full range of passive movement; and if the arm is abducted with assistance beyond 90° the patient can sustain the abduction by deltoid action (Fig. 14.12B). Thus the essential and characteristic feature in cases of torn supraspinatus tendon is inability to initiate gleno-humeral abduction. The usual explanation is that the early stages of abduction demand the combined action of the deltoid muscle, which supplies the main motive force, and the supraspinatus, which stabilises the humeral head in the glenoid fossa (like the workman’s foot against a ladder that is being raised from the ground).

Diagnosis. Complete tear of the rotator cuff must be distinguished from other causes of impaired gleno-humeral abduction, especially the painful arc syndrome and paralysis of the abductor muscles (as from poliomyelitis or nerve injury). Inability to initiate gleno-humeral abduction, with power to sustain abduction once the limb has been raised passively, is characteristic of a widely torn supraspinatus. In the painful arc syndrome the power of abduction is retained but the movement is painful.

Imaging. Examination by ultrasound scanning can identify a complete tear of the rotator cuff, but MR scans provide more detailed information on associated pathology in the surrounding structures (Fig. 14.13).

PAINFUL ARC SYNDROME (Supraspinatus syndrome)

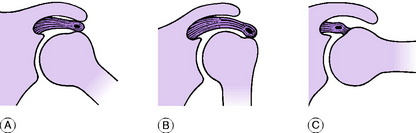

Cause. The pain is produced mechanically by nipping of a tender structure between the tuberosity of the humerus and the acromion process and coraco-acromial ligament.

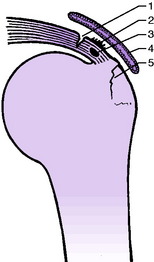

Pathology. Even in the normal shoulder, the clearance between the upper end of the humerus and the acromion process is small in the range of abduction between 45 and 160 °. If a swollen and tender structure is present beneath the acromion it is liable to get nipped during the arc of movement in which the clearance is small (Fig. 14.14A), with consequent pain. In the neutral position and in full abduction the clearance is greater and pain is less marked or absent (Figs 14.14B and 14.14C).

Five primary lesions can give rise to the syndrome (Fig. 14.15). In general, though, these labels only represent variations of a process of degeneration which is the underlying defect.

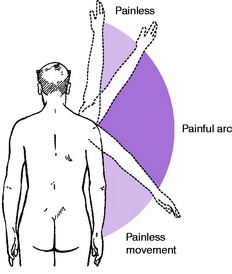

Clinical features. Whatever the primary cause, the clinical syndrome has the same general features, though they vary in degree. With the arm dependent pain is absent or minimal. During abduction of the arm pain begins at about 45 ° and persists through the arc of movement up to 160° (Fig. 14.16). Thereafter the pain lessens or disappears. In descent from full elevation pain is again experienced during the middle arc of the range: often the patient will twist or circumduct the arm grotesquely in an effort to get it down with the least pain. The severity of the pain varies from case to case. In cases of calcified deposit in the supraspinatus tendon the pain may be so intense that the patient is scarcely able to move the shoulder, or to sleep, and is driven to seek emergency treatment.

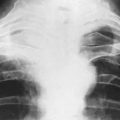

Radiographic features. These vary with the underlying cause. Plain radiographs will reveal a fracture of the greater tuberosity or a calcified deposit (Fig. 14.17). A calcified deposit is distinguished radiologically from an avulsed fragment of bone by the fact that it is homogeneous and does not show the trabeculation characteristic of bone. MR scanning may demonstrate some of the other causes from degeneration and partial tears of the rotator cuff.

Differentiation between the five primary causes of the syndrome is aided by the history and by radiography. A history of injury suggests a strain of the supraspinatus tendon or a lesion of the greater tuberosity, whereas a spontaneous onset suggests tendinitis, calcified deposit or subacromial bursitis. As noted, radiography will confirm or exclude a fracture or a calcified deposit (Fig. 14.17).

RUPTURE OF LONG TENDON OF BICEPS

The long tendon of the biceps is one of several tendons in the body that are prone to rupture without violent stress or injury. (Others are the supraspinatus tendon and the tendon of extensor pollicis longus.)

POLYMYALGIA RHEUMATICA

Polymyalgia rheumatica was described on page 166. It is worth mentioning again here because the soft tissues about the shoulders and the base of the neck are commonly the parts affected. The onset of this disorder of connective tissue is insidious, with aching pain and tenderness in the muscles of the shoulder girdle, neck, and spine, and severe ‘stiffness’ with substantial restriction of mobility of the shoulders, neck, and spine. There is also constitutional illness, with malaise, mild pyrexia, and night sweats, and elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Early treatment by prednisolone in high doses should be advised if there is a suspicion of giant cell arteritis, pending confirmation of the diagnosis by biopsy.

DISORDERS OF THE ACROMIO-CLAVICULAR JOINT

OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE ACROMIO-CLAVICULAR JOINT

Clinical features. There is pain, localised accurately to the acromio-clavicular joint and aggravated by strenuous use of the limb – especially in overhead work. On examination irregular bony thickening of the joint margins due to osteophytes may be felt. There is no soft-tissue thickening and no increase of local skin temperature. The total range of shoulder movements is not appreciably decreased, but pain in the region of the acromio-clavicular joint is exacerbated at the extremes of movement, especially on elevation of the arm towards the vertical: the arc of movement below 90 ° is painless, but above 90 ° pain develops and persists throughout the remainder of the arc to full elevation (compare painful arc syndrome, p. 268).

PERSISTENT ACROMIO-CLAVICULAR DISLOCATION OR SUBLUXATION

Treatment. Usually treatment is unnecessary, but if disabling pain persists operation is advised. A simple and effective method to achieve pain relief is to excise the lateral end of the clavicle. However, in younger patients the resultant instability may be troublesome and it may be preferable to reconstruct the joint by coraco-acromial ligament transfer combined with internal fixation of the coraco-clavicular joint.

DISORDERS OF THE STERNO-CLAVICULAR JOINT

EXTRINSIC DISORDERS SIMULATING SHOULDER DISEASE

DISORDERS OF THE BRACHIAL PLEXUS OR ITS ROOTS

The pain caused by pressure upon the brachial plexus or its roots is commonly attributed erroneously to an affection of the shoulder. Such pain varies in its precise distribution according to the site and nature of the nerve lesion. Usually it radiates from the base of the neck, across the top of the shoulder, and down the front, side, or back of the arm; thence it extends into the forearm, and often into the hand and fingers. Thus in its typical form the pain from a nerve lesion in the neck differs from the pain of a shoulder lesion, which typically does not extend below the elbow. The conditions which can result in brachial plexus symptoms are described in Chapter 12.

Affections that may cause referred symptoms in the distribution of the brachial plexus include prolapsed cervical intervertebral disc, osteoarthritis of the cervical spine, cervical rib, herpes zoster, and tumours involving the spinal cord or the component nerves of the brachial plexus.

1 Blundell Bankart, a technically brilliant English orthopaedic surgeon working in London, described the shoulder lesion in recurrent dislocation and the operation for its repair in 1923.

2 Vittorio Putti, Professor of Orthopaedics in Bologna, and Sir Harry Platt of Manchester, later President of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, were jointly credited with developing this operation in 1923.