Chapter 5 The Shoulder

The shoulder is a complex series of joints that provide an extraordinary range of motion. This extreme mobility is accomplished, however, at the expense of some stability. This lack of stability, combined with its relatively exposed position, makes the shoulder vulnerable to injury and degenerative processes. Pain may develop not only from primary disease of the shoulder but also by referral from disorders of thoracic and abdominal origin, and these sources should be kept in mind, especially when more obvious causes are not apparent.

Anatomy

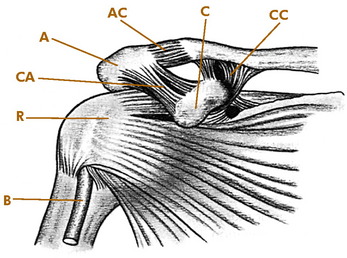

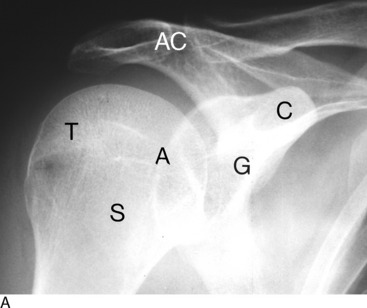

Four articulations constitute the shoulder joint: the glenohumeral, scapulothoracic, acromioclavicular (AC), and sternoclavicular joints. The stability of these joints is provided by a series of ligaments and muscles (Fig. 5-1).

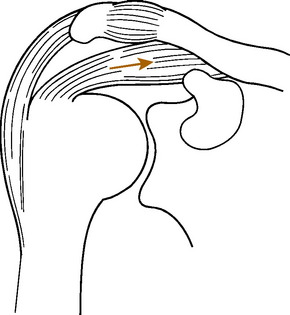

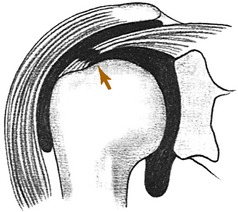

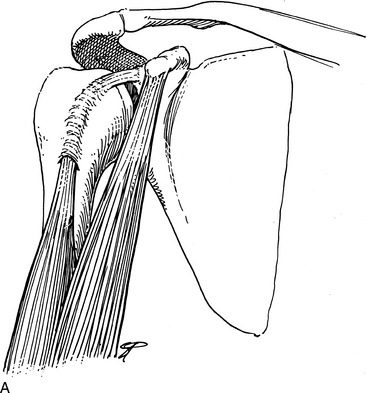

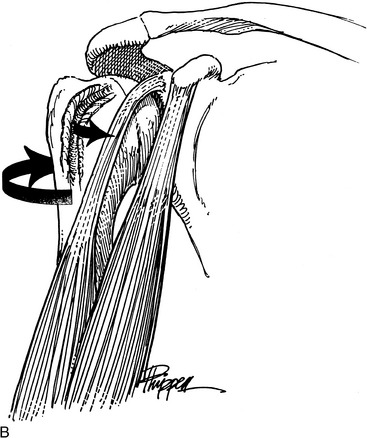

Motion of the arm results from the coordinated efforts of several muscles. With the initiation of shoulder motion, the scapula is first stabilized. The muscles of the rotator (musculotendinous) cuff, especially the supraspinatus, then steady the humeral head in the glenoid cavity and cause it to descend (Fig. 5-2). This prevents the rotator cuff from impinging against the acromion. Elevation of the arm results from a combination of scapulothoracic and glenohumeral joint movements. One third of total shoulder abduction is provided by forward and lateral movement of the scapula. The remaining two thirds occurs at the glenohumeral joint through progressively increasing activity of the deltoid and supraspinatus muscles. Thus, even in the complete absence of glenohumeral motion, scapulothoracic movement can still abduct the arm approximately 60 to 70 degrees.

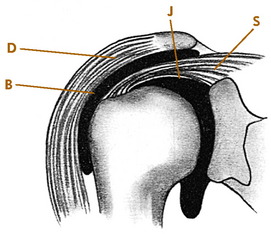

The coracoid, coracoacromial ligament, and underneath surfaces of the acromion and AC joint form a structure sometimes called the “coracoacromial arch.” The muscles of the rotator cuff (supraspinatus, teres minor, infraspinatus, and subscapularis) are separated from this overlying arch by the subacromial space. Bursal tissues occupy some of this space and may be affected by lesions of the musculotendinous cuff, AC joint, and adjacent structures (Fig. 5-3). They are frequently referred to as the subacromial bursa. Primary diseases of this bursa are rare, although secondary involvement is quite common. If bony abnormalities encroach on the subacromial space from above, the rotator cuff could be compressed as abduction occurs. When injections are given for rotator cuff disorders, it is the subacromial space that is injected.

Examination

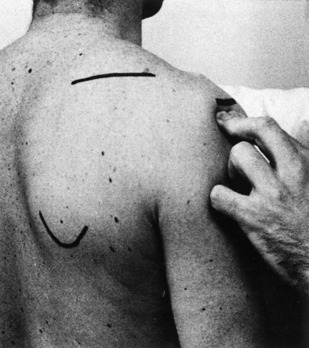

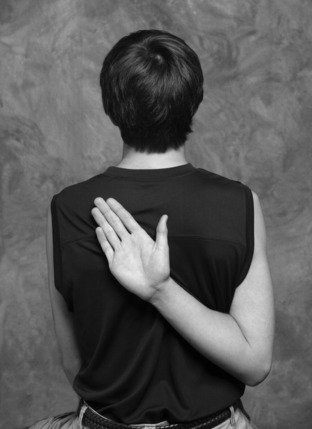

The examination is performed with both shoulders widely exposed (Fig. 5-4). The general contour of the shoulder is noted, as well as any atrophy or swelling. The shoulder is thoroughly palpated, and any areas of tenderness are determined. These are frequently located over the AC joint and the rotator cuff.

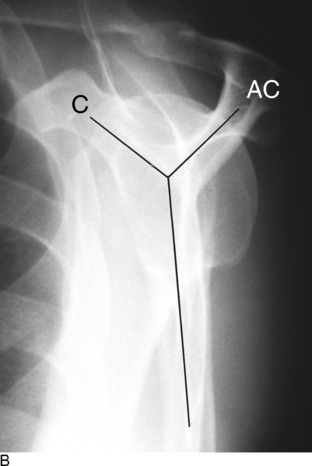

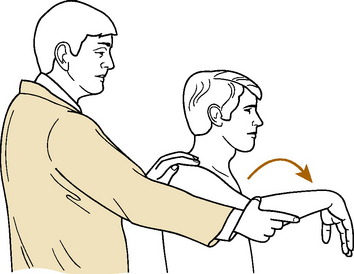

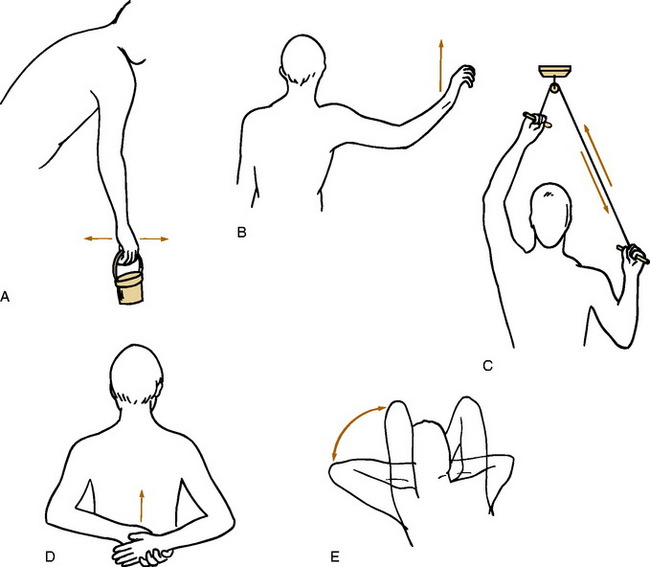

Active and passive ranges of motion are tested and compared with those of the opposite arm. The examiner should determine whether the scapula and humerus move together or independently. Any crepitus during the examination is also noted. Active motion is measured in abduction, forward flexion, and extension. External and internal rotation can be measured by instructing the patient to reach behind the head and then backward behind the shoulder blades. Limited internal rotation is often seen in conjunction with rotator cuff disorders. Involvement of the AC joint is tested by directing the patient to adduct the arm across the front of the chest and touch the opposite shoulder (Fig. 5-5). Pain with this test suggests AC or sternoclavicular disease. The strength of the shoulder, especially at 90 degrees of forward flexion and then at 90 degrees of abduction, is tested and compared with the opposite arm.

Roentgenographic Anatomy

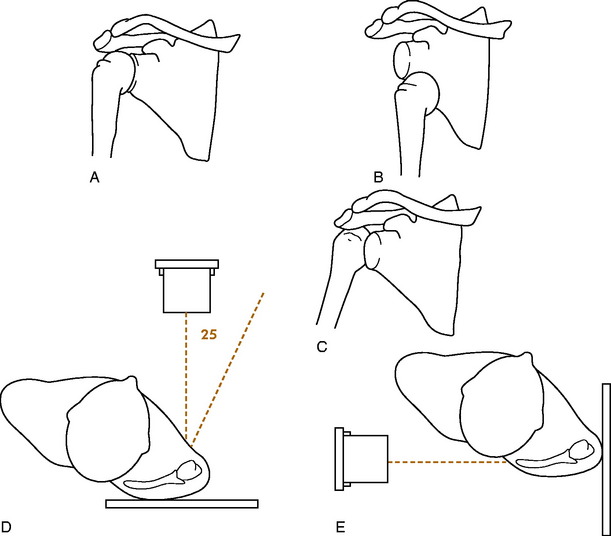

The shoulder is routinely examined by anteroposterior views with the arm rotated externally and internally (Fig. 5-6). A lateral view of the shoulder joint should always be taken. This may be obtained by utilizing a transaxillary or lateral scapular Y exposure. The scapular Y view is helpful in evaluating the shape of the acromion as well as assessing any bony abnormalities that could narrow the subacromial space. It is also valuable in determining if the humeral head is dislocated or not.

Disorders of the Rotator Cuff

TENDINITIS

A painful rotator cuff can develop at any age, although it is rare in children. It is sometimes related to chronic overuse. The term tendinitis has typically been used for this diagnosis, but the terminology is changing to reflect knowledge regarding the underlying pathology. Because the cellular changes associated with inflammation are often absent in these cases, the terms tendinopathy or tendinosis have been proposed. Small degenerative separations or “tears” of the rotator cuff may even develop over time. Scarring and thickening of the involved area of tendon and bursa occur, decreasing the distance between the cuff and the overlying coracoacromial arch. Bony abnormalities of the acromion may also be a factor in compromising this space. Pain and crepitus (“impingement”) may be noted when motions of the arm, especially abduction, squeeze and pinch these tissues between the humerus and the overlying arch. Even with an intact cuff, impingement may develop if the supraspinatus does not function effectively, allowing the humeral head to be pulled upward with deltoid contraction.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The major clinical manifestations are pain (especially at night for unknown reasons), tenderness, and occasionally atrophy. The patient is often unable to lie on the affected shoulder and may feel a locking or catching sensation with certain motions, especially abduction. The pain is often referred down the deltoid muscle. When abducting the shoulder, the patient may automatically turn the palm up, thereby externally rotating the shoulder, a maneuver that gives the rotator cuff more room beneath the coracoacromial arch. Active, palm-down abduction is frequently painful. Forced passive elevation of the arm may cause the supraspinatus to impinge against the acromion, causing pain. Pain may also be reproduced by internal rotation and forward flexion (Fig. 5-7).

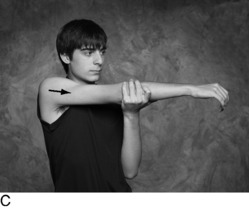

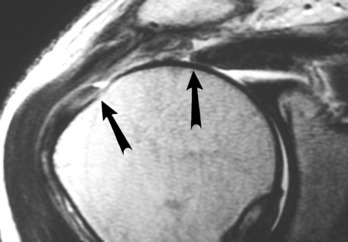

Maximum tenderness is usually noted over the supraspinatus insertion at the acromiohumeral sulcus because this is the most common area of involvement, although palpable tenderness may be difficult to elicit in obese or muscular individuals. Internal rotation is often decreased because of contracture of the posterior capsule (Fig. 5-8). There is usually little actual loss of muscle power. The pain and crepitus are most severe in the arc of motion between 60 and 120 degrees of abduction. This is where the traumatized soft tissues are maximally compressed between the tuberosity and the overlying arch.

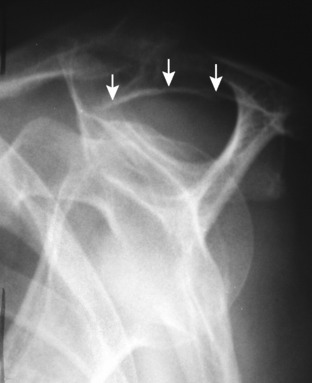

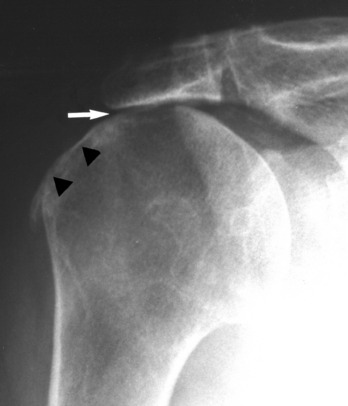

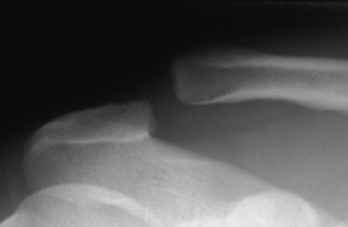

The roentgenogram is usually normal, but some sclerosis may be present in the tuberosity secondary to long-standing local irritation. Osteophytes or abnormalities in the shape of the acromion may be noted (Fig. 5-9).

TREATMENT

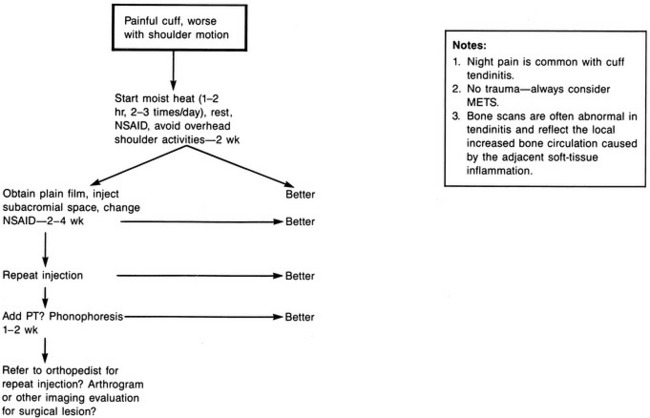

Improvement is usually seen within 3 to 5 weeks (Fig. 5-12). If it is not, a more serious cuff lesion, such as a rupture, should be suspected. At this point, the patient should be referred for orthopedic evaluation and possible magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Surgery is reserved for those cases that fail to respond to conservative treatment and patients who have reparable underlying pathology.

RUPTURES OF THE ROTATOR CUFF

Ruptures of the rotator cuff are almost always chronic in nature and result from continued deterioration and degeneration (Fig. 5-13). The separation may be partial or complete. Ruptures are uncommon before the age of 40 years, although they may occur in young athletes. Acute tears are rare. Many ruptures are completely asymptomatic.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Obtaining a history sometimes reveals a fall on the outstretched hand or an attempt to lift a heavy object, but usually there is no obvious injury. Pain and weakness may become progressively worse, and the patient notes an inability to abduct or flex the shoulder, depending on the area of the rupture. The pain is often referred down the deltoid muscle. Occasionally, the patient may have had a previous history of chronic impingement pain, and the diagnosis of rupture is often considered only when the patient fails to respond to the usual treatment for tendinitis.

If the rupture is partial, the clinical findings are similar to those seen in chronic tendinitis, and even with complete rupture, the shoulder may have a full range of motion because of continued function of the other rotator muscles and deltoid. Usually, however, with both partial and complete ruptures, there is at least some weakness in abduction or flexion. The weakness is usually most severe in abduction, because the muscle most commonly torn is the supraspinatus. (Supraspinatus rupture or weakness causes loss of the depressor effect, allowing the head to ride up, which increases the sense of grinding.) If the rupture is more anterior into the subscapularis, forward flexion may also be weak. Weakness against external rotation suggests rupture of the infraspinatus. It may be impossible to actively abduct the arm more than 45 to 50 degrees, after which further abduction is obtained by scapulothoracic motion. Tenderness at the site of the tear is a common finding, and with complete ruptures a defect in the cuff may be palpated through the deltoid muscle. Passive range of motion is frequently normal in the pain-free shoulder, although there is usually a positive impingement sign. Sometimes in complete massive tears, the patient can only “shrug” the shoulder and may have to use the opposite hand to raise the arm any further.

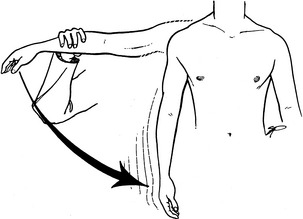

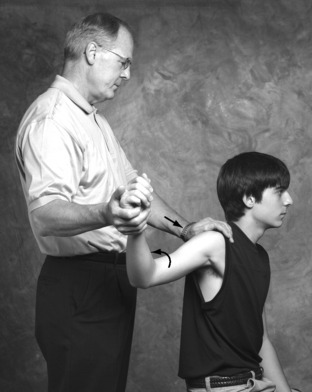

Atrophy of the cuff muscles is frequently present, and the “drop-arm” test may be positive if the tear is significant (Fig. 5-14). In this test, the arm is passively abducted to 90 degrees with the thumb pointing down, and then released. If the shoulder can maintain abduction, slight downward pressure is applied to the forearm, and the strength of the affected shoulder is compared with the normal shoulder. If pain is severe during the examination, lidocaine infiltration of the tender area can relieve the pain. The strength is then measured again. Inability to maintain shoulder abduction with this test is suggestive of a significant rotator cuff tear. Atrophy in the young is rare and should suggest nerve injury.

SPECIAL STUDIES

TREATMENT

Partial or small complete tears may respond to the conservative treatment program outlined for chronic tendinitis including occasional injections. Physical therapy (PT) and exercise are probably contraindicated in the presence of a separation. Occasionally, it is necessary to surgically repair the rupture and remove any impinging structures beneath the coracoacromial arch, especially in the young, active patient with high functional needs. Complete tears may also need repair if they are sufficiently disabling at any age. Often, however, there is very little loss of function and minimal pain, even with a complete rupture. In these patients, especially if they are relatively inactive, operative intervention is probably not justified.

CALCIFIC DEPOSITS IN THE ROTATOR CUFF

Calcium deposits in the rotator cuff tendon may be associated with pain and stiffness in the shoulder. Whether the calcific changes are a cause of symptoms or simply the result of degeneration is not known. Benign calcific deposits are a common incidental finding and probably result from degenerative changes in the same area where ruptures take place. They are most frequently found in the supraspinatus tendon. Most deposits remain small and deep in the tendon, and pain may be absent. Others may produce an inflammatory reaction and swelling, perhaps as the process of resorption takes place. Impingement of these swollen tissues against the overlying coracoacromial arch may then occur.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Roentgenographic examination in internal and external rotation usually reveals the deposit (Fig. 5-18). If the deposit is anterior in the subscapularis muscle or posterior, a transaxillary or Y view may be necessary to demonstrate it.

Disorders of the Biceps Tendon

TENOSYNOVITIS

CLINICAL FEATURES

The most common symptom is pain over the anterolateral aspect of the shoulder that may be referred down the anterior aspect of the arm. (Rotator cuff disorders usually refer pain down the lateral arm.) The most constant physical finding is tenderness to palpation over the bicipital groove. Active and passive shoulder motions are often restricted because of pain. Maneuvers that stretch the biceps tendon or cause it to glide in the groove may be painful. Forceful extension or abduction against resistance with the elbow extended and the forearm supinated may reproduce the pain (Fig. 5-19). Backward movement with the elbow extended may also be painful. The roentgenograms are usually normal.

TREATMENT

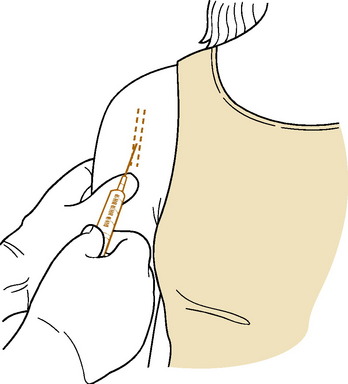

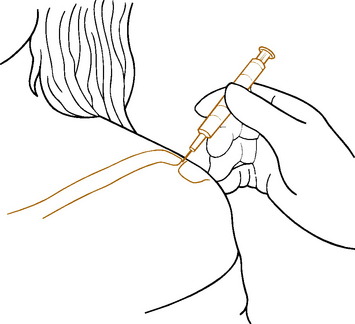

In the acute stage, treatment consists of rest, moist heat, and gentle range of motion exercises. All motions that stretch the biceps tendon should be avoided. A sling may be used temporarily. NSAIDs may be helpful, and local steroid injections into the tendon sheath are frequently beneficial (Fig. 5-20). The majority of cases respond well to conservative treatment. Surgery is recommended for those cases that fail to improve.

RUPTURE OF THE BICEPS TENDON

CLINICAL FEATURES

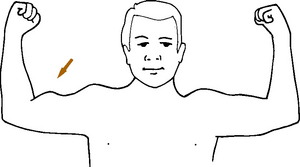

The onset is usually sudden. A sharp snap may be felt by the patient, followed by pain and weakness of the arm. The diagnosis is easily made by the observation of an abnormally large mass in the arm that represents the retracted muscle belly of the long head of the biceps (Fig. 5-21). There may be some loss of elbow flexion power, but after the discomfort subsides, the amount of weakness is usually minimal.

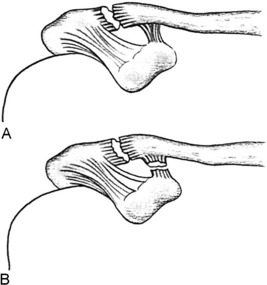

SUBLUXING BICEPS TENDON

The biceps tendon may occasionally sublux or dislocate out and back from its bed in the bicipital groove (Fig. 5-22). The usual cause is a tear in the overlying subscapularis tendon as the result of degenerative changes, but the condition may result from a congenitally shallow groove. The disorder may also occur in young patients on forceful external rotation and abduction of the shoulder. Recurrences are frequent and may be reproducible by the patient. Tenosynovitis frequently develops and leads to pain.

Frozen Shoulder (Adhesive Capsulitis)

CLINICAL FEATURES

The onset is usually gradual and begins in the fifth decade. Three stages are sometimes described: freezing, frozen, and thawing. The disorder may develop during a period of inactivity in the use of the extremity or after a relatively minor injury to the shoulder, but usually there is no precipitating event. Pain is a constant symptom but frequently does not occur until much of the shoulder motion has already been lost. Pain is usually well localized in the region of the rotator cuff and may radiate down the deltoid and anterior aspect of the arm. It frequently interferes with sleep, especially when the patient attempts to lie on the affected shoulder.

TREATMENT

The most important facet of treatment is prevention. Every attempt should be made to maintain motion in the shoulder during periods when the patient may be inactive because of disease or injury. Once the disease process has begun, treatment is directed at the relief of pain and restoration of motion. Moist heat, sedation, and analgesics are prescribed as necessary. Because rotator cuff dysfunction is often a significant source of pain, a local injection of a steroid–lidocaine mixture into the subacromial space may also prove beneficial. Injection of the shoulder joint itself may also be helpful. Pendulum and overhead pulley exercises are begun as soon as possible and initially are performed on an hourly basis (Fig. 5-23). (Frequency of exercise is far more important than duration.)

Snapping Scapula

CLINICAL FEATURES

The onset is usually gradual, but the process is frequently precipitated by a traumatic event. The snapping is often palpable and painful. The origin of these noises can frequently be well localized by the patient to a specific area in the scapulothoracic articulation. Roentgenograms of the scapula, including oblique views, are obtained to discover such lesions as exostoses and tumors when they are present (Fig. 5-24).

TREATMENT

If the roentgenograms are normal, PT, rest, and local steroid injections often relieve the pain. An exercise program is important. Correction of poor posture is also frequently beneficial. If the snapping is secondary to tumor or exostosis and the pain and disability are sufficient to justify surgery, the involved area of the scapula is removed surgically. Most patients seem to tolerate the symptoms, which appear to resolve on their own most of the time, and surgery is rarely required.

Distal Clavicle Osteolysis

Clinically, there is local tenderness and a positive cross-body adduction test.

Plain roentgenographic evaluation reveals loss of bone detail of the distal tip of the clavicle because of hyperemia and osteopenia (Fig 5-25). Bone scanning is abnormal, although the test is usually not required to establish the diagnosis.

Treatment is symptomatic. NSAIDs and heat are helpful. Weightlifting activities may need to be discontinued temporarily. Steroid injection into the AC joint is often helpful. Excision of the tip of the clavicle may rarely be required. How much treatment is appropriate for the recreational athlete is considered on a case-by-case basis.

Unicameral Bone Cyst

CLINICAL FEATURES

The roentgenographic appearance is usually characteristic (Fig. 5-26). The lesion appears as a relatively large radiolucent mass that is wider at the growth plate and narrower at the diaphysis. The cortex is usually expanded and thinned, but the lesion never penetrates into the soft tissue. A pathologic fracture is commonly present. As the lesion matures over time, it “migrates” away from the growth line and shrinks in size. It commonly disappears completely as it drifts toward the midshaft, although some lesions are said to survive into adulthood. There is very little periosteal new bone reaction around the cortex. MRI is helpful in disputed cases but is rarely needed because of the typical radiographic appearance of the lesion.

Serratus Anterior Paralysis

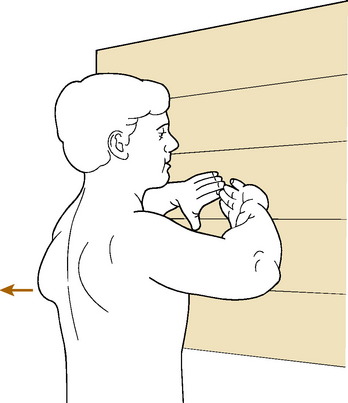

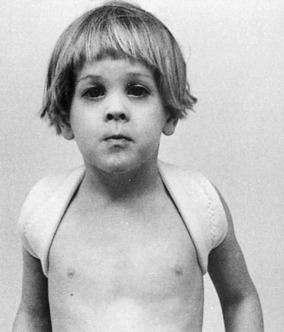

The serratus anterior pulls the scapula forward, stabilizing it when pushing. Paralysis of the long thoracic nerve can lead to the characteristic winging, which is most obvious when the patient does a push-up against a wall (Fig. 5-27). The etiology may be direct trauma, but usually no cause is found.

Glenohumeral Dislocation and Instability

Ninety-five percent of dislocations of the shoulder are anterior in direction and usually result from a fall on the externally rotated, abducted arm (Fig. 5-28). This force levers the humerus out of the glenoid cavity into its anterior position. Anterior dislocation is the most common cause of instability.

Multidirectional instability is a condition in which glenohumeral dislocation or subluxation can occur in multiple directions. The main abnormality in this form of instability is generalized excessive laxity of the joint capsule, and the disorder is considered to be nontraumatic in nature, in contrast to the unidirectional type. These patients often have signs of ligamentous laxity in other joints.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The diagnosis of the acute dislocation is usually not difficult. Clinically, the acromion is much more prominent than normal, and there is an absence of the normal fullness of the humeral head beneath the deltoid and acromion process. Little movement of the shoulder is possible without severe pain. With anterior dislocations, the arm is held externally rotated; the anterior shoulder is full; and internal rotation is painful. In posterior dislocations, the arm is held in internal rotation with the forearm resting on the abdomen; the anterior portion of the shoulder is flat; and external rotation is painful (the arm is locked in internal rotation). The integrity of the neurovascular structures of the arm should always be assessed, especially the axillary nerve. Numbness in the middle of the deltoid may be the only obvious finding of axillary nerve damage because motor function is often difficult to test due to pain (Fig. 5-29).

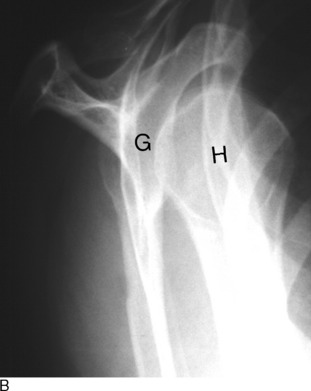

Roentgenographic evaluation is mandatory. The radiographic diagnosis in cases of anterior dislocation is usually easy, but interpretation is sometimes difficult with posterior dislocation, and the diagnosis is commonly missed (Fig. 5-30). A “true” anteroposterior view of the shoulder may be helpful, but a lateral view of the glenohumeral joint is essential. A variety of lateral views may be performed (transaxillary, transscapular Y). If there is any doubt about the diagnosis, some type of lateral view of the glenohumeral joint must be taken. Some dislocations may only be apparent on the lateral view (Fig. 5-31).

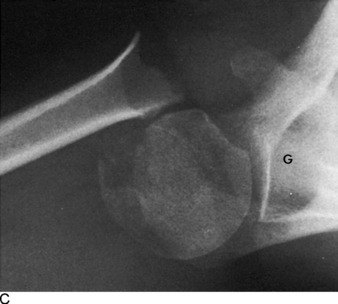

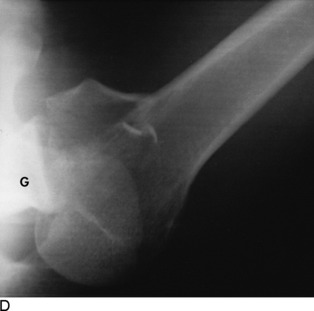

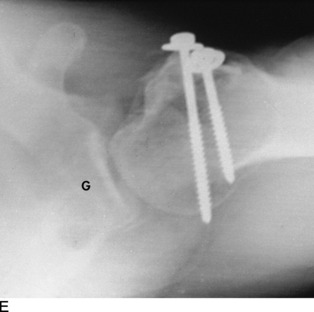

FIG. 5-31 A and B, Transaxillary lateral views of the glenohumeral joint. Even with a fracture or dislocation, the arm can be gently abducted enough to obtain a view from below or above. It may be done in a standing or supine position. C, The roentgenographic appearance. Also present is a displaced fracture of the surgical neck of the humerus, but the humeral head is properly positioned in the glenoid (G). D, A posterior fracture-dislocation. E, The injury in D is reduced and the fracture has been internally fixed.

The diagnosis of instability may be difficult if there is no clear history of an acute dislocation. Unidirectional instability following posterior dislocation is rare, but anterior instability commonly develops in the young patient following an anterior dislocation. It may even result from stretching of the anterior capsule by the repetitive throwing motion. Anterior dislocation in the young often causes damage to the labrum and capsular ligaments, usually called the “Bankart lesion.” This injury can lead to instability and even recurrent dislocations, often with minor shoulder movement, such as simply turning off a light from bed. The common complaint is that the shoulder “goes out” when the arm is placed in the throwing position. In these cases, there may be apprehension when this maneuver is reproduced on clinical examination (Fig. 5-32).

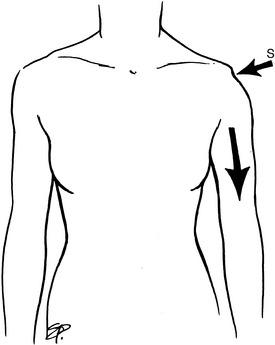

The diagnosis of multidirectional instability may be difficult if there is no history of frank dislocation, which is commonly the case. The sulcus test is helpful. This test assesses inferior movement of the humeral head. With the patient standing and the arms hanging, the arms are pulled inferiorly (Fig. 5-33). A sulcus will form between the acromion and humeral head in cases of multidirectional instability. Examination of other joints may reveal generalized laxity.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

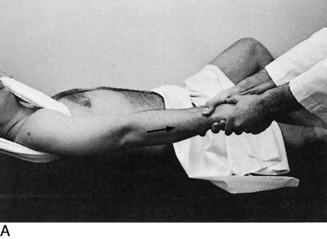

Shoulder dislocations are usually reducible without use of general anesthesia. Intravenous sedation or analgesia is often helpful. Gentle, straight traction on the arm is usually sufficient to reduce both the anterior and posterior dislocation (Fig. 5-34). If straight traction does not reduce the dislocation, Stimson’s method may be used for the anterior dislocation. The patient is placed in a prone position with the affected arm hanging over the side of the table. A 5- to 10-kg weight is tied to the wrist for traction. As the shoulder muscles relax, spontaneous reduction frequently occurs. If the shoulder remains dislocated, reduction with the patient under a general anesthetic is usually necessary. Open reduction is rarely required.

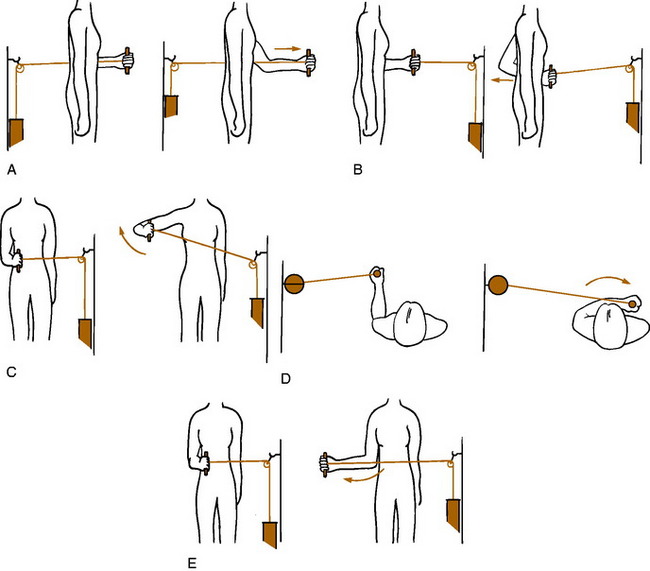

Primary dislocations in either direction in patients younger than 30 years have a high rate of recurrence, often with little trauma. It had been theorized that prolonged immobilization for 3 to 4 weeks would encourage better capsular healing and prevent recurrent dislocation. It now appears that extended protection offers no benefit against recurrence and that the likelihood of recurrence is determined primarily by the age of the patient at the time of the injury, regardless of the form of treatment after the reduction. Patients younger than the age of 30 have a 50% recurrence rate, irrespective of the type or length of immobilization following reduction. Thus, following reduction, the arm is simply rested in a sling for a few days, and motion is gradually allowed as symptoms subside. Rehabilitative exercises are often helpful (Fig. 5-35). The patient is educated to avoid positions of known instability, usually external rotation and abduction with the common anterior dislocation. Recurrence risk is directly proportional to the level of activity and inversely to age. There is almost a 100% rate of recurrence after a third dislocation, and recurrent dislocations in either direction usually require corrective surgery.

Acromioclavicular Dislocation

AC dislocations and “separations” usually occur as a result of a fall on the shoulder or from a direct blow to the top of the shoulder. The acromion is driven away from the clavicle. They are graded I through V. Grade I is a simple AC contusion or strain. In grade II, there is rupture of the AC ligaments. Grade III includes the additional rupture of the coracoclavicular ligaments. The uncommon, severe grades IV and V involve more significant displacement, often with penetration through the overlying muscle. Grades I and II are sometimes called incomplete, and grades III through V called complete (Fig. 5-36).

CLINICALFEATURES

These injuries are characterized by tenderness and swelling over the AC joint. The outer clavicle is usually elevated in both complete and incomplete dislocations (Fig. 5-37). Downward traction on the arm may increase the deformity.

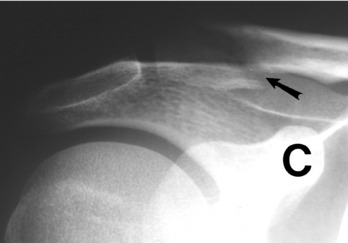

Complete dislocations may be differentiated from incomplete dislocations by an anteroposterior roentgenogram taken while the patient has a 10-kg weight hanging from both arms. (The patient should not hold the weights.) If complete rupture of the coracoclavicular ligaments has occurred, widening between the coracoid process and the clavicle will be present on the affected side (Fig. 5-38).

Sternoclavicular Dislocation

The injury usually produces a tender, visible prominence at the sternoclavicular joint. Some discomfort with shoulder motion is usually present.

Avascular Necrosis (Osteonecrosis)

CLINICAL FEATURES

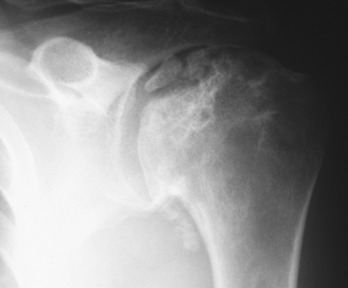

The early stage is asymptomatic, but later, nonspecific symptoms such as joint pain and stiffness develop. Later in the disease, the clinical findings are similar to osteoarthritis as deformity and collapse of the head occur. By this time, plain films usually reveal the extent of the disorder (Fig. 5-39). MRI is highly sensitive to the vascular changes in early cases. In late stages, bony collapse of the humeral head occurs, and arthritic changes develop involving the entire joint.

Degenerative Arthritis

Primary degenerative arthritis of the glenohumeral joint is relatively uncommon. Most often, it is a secondary process, usually the end stage of chronic rheumatoid arthritis, avascular necrosis, or long-standing chronic rotator cuff disease (cuff-tear arthropathy; Fig. 5-40). It may also be the result of recurrent shoulder dislocations or severe fractures of the shoulder joint. Chronic pain and limited shoulder motion are common, and atrophy and crepitus are frequently present.

The AC joint is a common site of osteoarthritis. Local tenderness is usually present, and the crossover maneuver is painful. Symptomatic treatment with NSAIDs and local injections of cortisone into the joint are helpful (Fig. 5-41). Distal clavicle resection is the surgical treatment of choice and offers a high success rate with low morbidity.

Fractures of the Shoulder Region

FRACTURES OF THE CLAVICLE

The clavicle is the only rigid, bony connection between the shoulder and the chest, and it functions to hold the shoulder upward and backward. Clavicle fractures are common injuries in both children and adults (Fig. 5-42). Examination usually reveals a tender deformity. Some tenting of the skin may be present, but the skin is rarely penetrated. Neurovascular disruption is uncommon.

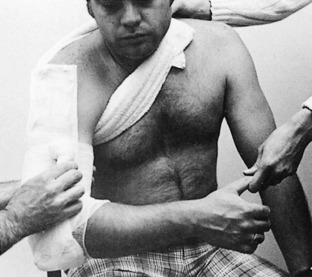

Historically, treatment has been directed at reduction with immobilization using a canvas figure-8 strapping system (Fig. 5-43). Reduction can sometimes be obtained by manipulation, but it is difficult to maintain, and some element of overriding and overlap seem inevitable in most cases. The strapping system must be constantly retightened to function properly, and pressure problems in the axilla sometimes occur (discomfort, venous congestion, skin pressure, nerve dysfunction), which often requires frequent readjustment of the dressing, often to the point that it loses its effectiveness. As a result, the use of a simple sling has been evaluated as an alternative treatment method, and it was found that the healing rate was the same using the sling alone. If the figure-8 bandage is used, discomfort can be relieved by having the patient lie down and temporarily abduct the arms. The addition of a sling may also be helpful.

Fractures lateral to the coracoclavicular ligament may be managed conservatively if they are relatively undisplaced (Fig. 5-44). A sling only is used. The figure-8 dressing should not be used for these since it can cause further displacement. The treatment of displaced lateral fractures is controversial because of the high nonunion rate and should be referred for orthopedic consultation.

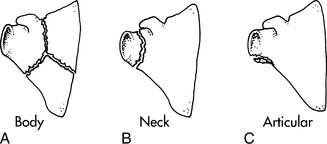

FRACTURES OF THE SCAPULA

Fractures of the scapula usually result from a direct blow or fall (Fig. 5-45). Fractures that do not involve the articular surface of the glenoid cavity require little treatment. A sling or shoulder immobilizer may be used for 1 to 2 weeks until the pain subsides. Gentle motion of the shoulder is encouraged as soon as possible, and the results are usually excellent. The rare fracture that involves the shoulder articulation may require more extensive surgical treatment (Fig. 5-46).

FRACTURES OF THE PROXIMAL HUMERUS

Minimally displaced or impacted fractures of the surgical neck of the humerus are common in older patients, especially women (Fig. 5-47). Slight degrees of malalignment may be accepted. Treatment consists of a sling for 4 weeks. Pendulum exercises are performed in the sling after 2 weeks. All immobilization is discontinued after 4 weeks, and range of motion exercises are increased. A hanging cast should not be used in these fractures because it may disimpact the bony fragments. The disability in this injury results not from the fracture itself, which usually heals readily, but from the secondary stiffness that develops in the shoulder, especially in the older patient. Range of motion may take several months to return. PT may be helpful if motion is slow to return. Because this fracture is often seen in the osteoporotic female, a workup for osteoporosis, including bone density studies, should be considered.

Fractures of the tuberosities of the upper humerus may occur from a fall or in association with a shoulder dislocation (Fig. 5-48). Undisplaced fractures require only a sling for 7 to 10 days, followed by early range of motion exercises. Patients with fractures that are displaced more than 5 to 10 mm should be referred. Such fractures frequently require open reduction and internal fixation. If this is not performed, a bony impingement to abduction could result.

FRACTURES OF THE SHAFT OF THE HUMERUS

Fractures of the shaft of the humerus usually heal well with nonoperative treatment. The function of the radial nerve should always be evaluated because it may be injured in its course around the humeral shaft.

Manipulative reduction with the patient under local anesthesia may be required, but distraction of the fracture fragments should be avoided. With the patient sitting on a stool and leaning forward, the weight of the arm frequently reduces the fracture (Fig. 5-49). The wrist is supported to overcome apprehension, but the elbow should hang free. Gentle traction and countertraction are applied, and the fracture fragments are manipulated to correct any angulation. The fracture is immobilized by a cast brace or by the application of a U-shaped plaster splint (Fig. 5-50). Additional fixation may be obtained by strapping the humerus to the chest wall. Healing is usually complete by 10 to 12 weeks. (This form of fracture care requires frequent reevaluation and readjustment of the brace system. Unless the treating physician has a special interest and expertise in fracture care, this injury is best treated by an orthopedic surgeon.)

INFERIOR SUBLUXATION OF THE HUMERAL HEAD

Inferior displacement of the head of the humerus may occur as a result of the following: (1) fractures about the shoulder area (Fig. 5-51), (2) local neurogenic impairment, such as brachial neuritis, and (3) strokes or other central nervous system (CNS) disorders. The most common cause is “hypotonicity,” which may develop in conjunction with fractures of the upper humerus or dislocations of the glenohumeral joint. When the musculoskeletal injury heals, muscle tone usually returns to normal, and the abnormal increase in acromiohumeral distance disappears. Simple strengthening and range of motion exercises after the injury has healed are the only necessary treatment. The position returns to normal in a few weeks.

Shoulder Pain From Other Origins

THORACIC CAUSES OF SHOULDER PAIN

Although most disorders of intrathoracic origin will cause chest pain, shoulder discomfort is not uncommon and may even be the main presenting complaint. Diseases of cardiac origin (such as pericarditis) commonly cause left arm and shoulder pain. Cardiac pain may also be referred to the neck, lower jaw, and interscapular area. The pain associated with ischemic disease is usually exertional but may occur at rest and cause more confusion. Clinically, there is usually no tenderness or aggravation of the pain by neck or shoulder motion.

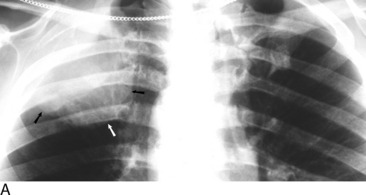

Pulmonary diseases (such as carcinoma, pneumonia, abscess) may also result in shoulder pain. Of special interest are tumors of the superior sulcus of the lung (Pancoast). This tumor produces a syndrome by virtue of its growth in the thoracic inlet. This region is bounded roughly by the first rib, the first costal cartilage, the manubrium, and the body of T1. The apex of the lung occupies most of the area. The superior pulmonary sulcus is a groove in the lung tissue made by the subclavian artery as it crosses the apex of the lung, and because the majority of apical lung tumors occur in relation to this sulcus, they are often called superior sulcus tumors. The structures in this area are the internal jugular and subclavian veins; the vagus, phrenic, and recurrent laryngeal nerves; the subclavian and common carotid arteries; the eighth cervical and first thoracic nerves; and the stellate ganglion and sympathetic chain. Any of these structures may be involved, and therefore the symptoms may be variable and complex. Pain is the most common initial complaint. Its distribution is often wide and unusual, frequently being present throughout the shoulder, scapular or infrascapular area, upper anterior portion of the chest, arm, neck, and axilla. Other components of this syndrome include Horner’s syndrome, weakness and sensory disturbances on the involved side (possibly because of involvement of the lower portion of the brachial plexus), supraclavicular fullness, venous distention, and edema of the extremity. A superior sulcus tumor should always be kept in mind in patients with neck or shoulder pain, especially if there is a history of smoking. Shoulder roentgenograms may reveal the lesion, but usually a more complete roentgenographic examination is needed (Fig. 5-52).

MISCELLANEOUS CAUSES

Malignant tumor, either primary, locally spread, or metastatic from a distant origin, may also be the cause of shoulder pain. The diagnosis may be obvious in the patient with a known history of malignancy. The major sources are tumors of thyroid, prostate, breast, lung, and kidney and Hodgkin’s disease. The most common primary tumor that metastasizes to bone is multiple myeloma. The shoulder is less commonly involved than the ribs, spine, and pelvis. Pathologic fractures may occur but are uncommon in the upper extremity. Plain roentgenograms may be normal because more than 50% bone destruction is needed before destructive changes become apparent on plain films. Bone scanning is usually helpful, but myeloma and some aggressive sarcomas may destroy bone so fast that repair cannot occur, thereby resulting in a false-negative study.

Paget’s disease may also cause localized bone pain (see Chapter 18). As a result of periosteal bone formation impinging on cranial and spinal nerves, impairment of nerve function may even occur. Most patients with Paget’s disease have minimal or no symptoms. The onset of increased pain in an area of Paget’s disease should suggest sarcomatous degeneration.

Shoulder-hand syndrome, a form of reflex neurovascular dystrophy (sometimes called complex regional pain syndrome), is a poorly understood disorder (see Chapter 18). The disease is probably caused by reflex sympathetic stimulation analogous to that proposed for causalgia. The patients are usually older than 50 years and often have had a recent acute illness, frequently a myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), pulmonary disorder, or minor musculoskeletal trauma. The patient develops pain, stiffness in the shoulder, and swelling and vasomotor phenomena in the involved extremity. There is a marked variability in the intensity of the pain, duration of acute symptoms, and extent of dystrophic change. A frequent complication is frozen shoulder. Treatment is nonspecific and includes (1) an active exercise program facilitated by analgesics, (2) physical therapy, (3) a trial of a corticosteroid (prednisone, 10 to 20 mg/day) for a short time, and (4) stellate ganglion blocks if all other forms of medical management are unsuccessful. The condition usually resolves on its own in the course of several months.

Carpal tunnel syndrome (see Chapter 7) is a common cause of shoulder pain. Although the predominant symptoms occur in the hand, they are frequently accompanied by arm and shoulder pain that radiates upward from the arm and forearm. Carpal tunnel syndrome and cervical disc syndrome with radiculopathy also occasionally occur at the same time and involve the same extremity. This situation is called the “double-crush” syndrome. Under this circumstance, then, there may be two causes of shoulder pain, neither of which has its origin in the shoulder itself.

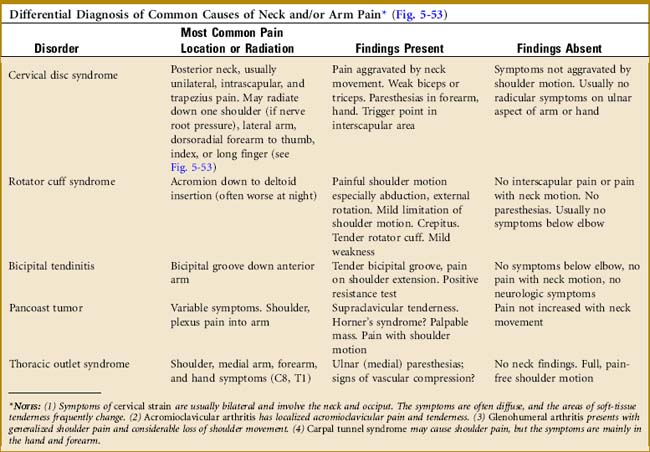

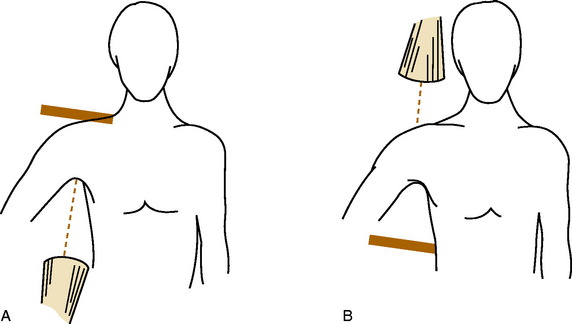

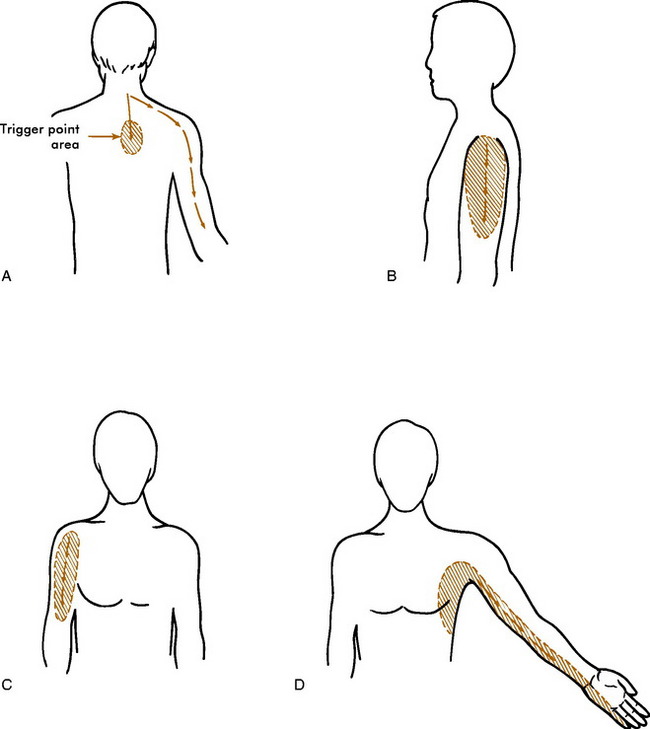

FIG. 5-53 General pain distribution of common neck and arm disorders. A, Cervical disc syndrome. B, Rotator cuff syndrome. C, Bicipital tendinitis. D, Disorders involving the lower portion of the brachial plexus (Pancoast tumor, thoracic outlet syndrome). When the shoulder pain has a visceral origin, the patient sometimes recognizes it as “deep” and perhaps not arising in the exact region where it is felt. NOTE: Symptoms such as pain and numbness that cross two joints are usually from nerve involvement, the nerve being the only structure that spans joints for such a distance.

Almekinders LC. Tendinitis and other chronic tendinopathies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:157-164.

Arendt EA. Multidirectional shoulder instability. Orthopedics. 1988;11:113-120.

Bacevich BB. Paralytic brachial neuritis. Case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:262-263.

Bush LH. The torn shoulder capsule. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:256-259.

Cofield RH. Rotator cuff disease of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:974-979.

Cohen BL. Treatment of shoulder complaints. Lancet. 2004;363:492.

Cox JS. Current treatment of acromioclavicular joint dislocation. Orthopedics. 1992;15:1041-1051.

Crass JR, Craig EV. Noninvasive imaging of the rotator cuff. Orthopedics. 1988;11:57-64.

DePalma AF. Surgery of the shoulder, ed 2. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1973.

Dillin L, Hoaglund FT, Scheck M. Brachial neuritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:878-880.

Ebell MH. Diagnosing rotator cuff tears. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1587-1588.

Goss TP. Anterior glenohumeral instability. Orthopedics. 1988;11:87-95.

Grant JC. A method of anatomy, ed 6. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1958.

Harrast MA, Rao AG. The stiff shoulder. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2004;15:557-573.

Hawkins RJ, McCormack RG. Posterior shoulder instability. Orthopedics. 1988;11:101-107.

Klauser A, Frauscher F. Treatment of shoulder complaints. Lancet. 2004;363:491-492.

McLaughlin HL. The “frozen” shoulder. Clin Orthop. 1961;20:126.

Moseley HF. Ruptures of the rotator cuff. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, 1952.

Murrell GA, Walton JR. Diagnosis of rotator cuff tears. Lancet. 2001;357:769-770.

Neer CS2nd, Craig EV, Fukuda H. Cuff-tear arthropathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:1232-1244.

Parsons TA. The snapping scapula and subscapular exostoses. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1973;55:345-349.

Warner JJ. Frozen shoulder: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;3:130-140.

Wilkins RM. Unicameral bone cysts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:217-224.