Chapter 10 The Hip

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint in which the femoral head articulates deeply into the acetabulum. This deep fit, combined with thick ligamentous and muscular supporting structures, makes the hip extremely stable but relatively inaccessible. Therefore, the diagnosis of disorders of the hip is sometimes difficult.

Anatomy

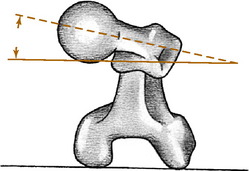

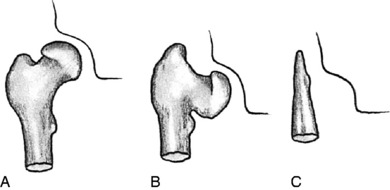

The proximal portion of the femur consists of a head, neck, and greater and lesser trochanters. The axes of the neck and femoral shaft form an angle in the anteroposterior plane: the neck–shaft angle, or “angle of inclination.” This normally measures 125 to 130 degrees. An increase in this angle is termed coxa valga, and a decrease is termed coxa vara. The neck and shaft also form an angle in the transcondylar plane that is referred to as the angle of femoral torsion (Fig. 10-1). Normal femoral torsion is 40 degrees in children, and this decreases to 15 to 20 degrees in adults. Excessive femoral torsion is termed anteversion or antetorsion and is sometimes responsible for in-toeing. A decrease in the normal femoral torsion is termed retroversion or retrotorsion and may cause an out-toeing gait.

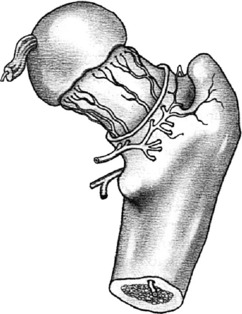

The vascular anatomy of the femoral head is of critical importance in many disorders of the hip. The main sources of blood supply are the retinacular and intramedullary vessels, both of which course from the intertrochanteric region proximally to nourish the femoral head (Fig. 10-2). Diseases or injuries that compromise the circulation may damage the viability of the femoral head and lead to avascular necrosis.

Among the nerves that supply the hip joint is the obturator nerve. This nerve also supplies a sensory branch to the medial side of the thigh and motor supply to some of the hip adductors. Irritation of this nerve from hip joint disease may result in referred pain along the inner aspect of the knee and thigh that may cause confusion with disorders of the knee joint. Therefore, complaints of pain in this area in the absence of physical findings in the knee should always draw attention to the hip joint.

Examination

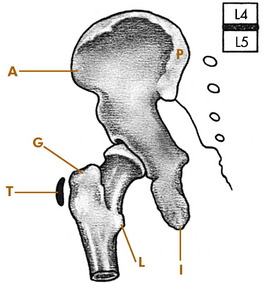

Several bony landmarks are available for orientation on physical examination. The anterior and posterior superior iliac spines and iliac crest are easily palpable because they are not crossed by any muscles (Fig. 10-3). The proximal portion of the iliac crest lies at the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra. The greater trochanter is palpable laterally, and the pubic symphysis is palpable anteriorly. The femoral head lies approximately 2.5 cm distal and lateral to the point where the femoral artery passes beneath the inguinal ligament. This relationship should be recalled when performing venipuncture from the femoral vein. A needle passed through the vein may enter the hip joint and introduce infection into the hip. All femoral venipuncture sites should therefore be meticulously scrubbed and prepared before needle insertion.

Roentgenographic Anatomy

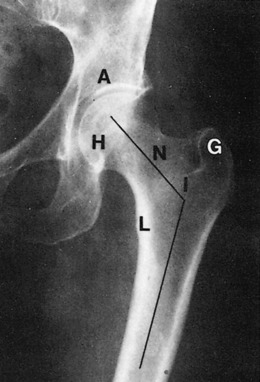

The roentgenographic study of the hip joint should include views in the anteroposterior and lateral planes (Fig. 10-4). The lateral view maybe either a “true” lateral or a “frog leg” exposure that is taken with the hips in maximum external rotation.

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

DDH is frequently bilateral, and although the cause is unknown, heredity appears to play a role. Females are affected nine times more often than males, and although the condition may affect both hips, the left is three times more often involved. Firstborn children or children born by breech deliveries also have a higher incidence of the disorder. It is occasionally present in association with clubfoot and congenital muscular torticollis deformities.

CLINICAL FEATURES

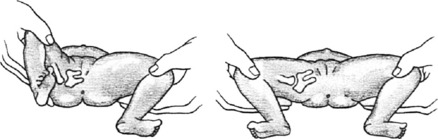

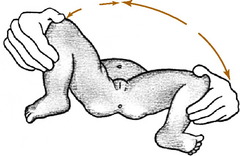

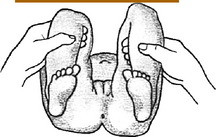

There are no symptoms in the newborn, but most cases are detectable at birth. The clinical picture of the unstable hip will range from minimal findings to obvious frank dislocation, depending on the age of the child. In the newborn, provocative maneuvers, such as Barlow’s and Ortolani’s tests, are commonly used to detect instability. The tests are similar. The Ortolani test refers to the gentle reduction of the dislocated hip by abduction of the flexed hip (Fig. 10-5). This is often accompanied by a soft “clunk,” sometimes called the click of entry. In Barlow’s test, the hip is purposely dislocated by gentle downward pressure of the flexed, adducted hip. With posterior pressure, the femoral head will be displaced out of the acetabulum if the hip is unstable, sometimes called the click of exit. The head is then reduced by gentle abduction of the flexed hip by performing Ortolani’s maneuver. Barlow’s test should not be performed excessively, because it could make the problem worse. Occasionally, this maneuver may result only in a sensation of excessive gliding without an obvious dislocation. This may be an indicator that the hip is subluxable and therefore unstable. Soft clicks sometimes felt during abduction–adduction movements are not considered pathologic unless other findings are present.

If the diagnosis is made late, the hip is less flexible, and the ability to reduce the dislocated hip by the provocative maneuvers is lessened. At this time, the physical findings may include asymmetry of the skin folds and limited abduction (Fig. 10-6). If the hip is dislocated, it may not be reducible, and other signs may be present, such as shortening of the extremity (Fig. 10-7).

The roentgenographic examination is usually not very helpful when the patient is younger than 3 months of age unless a complete dislocation is present. After this age, a delay in the ossification of the femoral head is frequently noted (Fig. 10-8). The acetabulum may be more inclined vertically, and the acetabular index is often increased. If subluxation or dislocation has occurred, upward and outward displacement of the femoral head will be seen.

Ultrasonography is useful in congenital hip dysplasia, especially in high-risk infants (such as those who are breech delivered or who have a positive family history) or those with uncertain clinical findings. Among its benefits is the elimination of exposure to radiation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may eventually be helpful, but the diagnosis can usually be established by other means.

TREATMENT

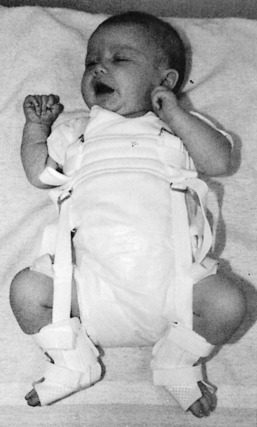

The objective of treatment is to reduce the femoral head into the acetabulum and maintain that reduction. By maintaining the hip in the reduced position, normal development of the hip joint structures and deepening of the acetabulum are encouraged. A variety of external devices are available for the treatment of hip dysplasia or dislocation, the most functional of which is the Pavlik harness (Fig. 10-9). The brace is usually worn for several weeks until the hip is stable.

Legg–Calvé–Perthes Disease

The disease is frequently divided into three stages. The early stage of the disease is characterized by synovitis of the hip joint and early ischemic changes in the ossific nucleus of the femoral head. Roentgenograms taken at this stage reveal joint swelling that may result in lateral displacement of the femoral head. An increase in the opacity of the ossific nucleus is usually present (Fig. 10-10).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

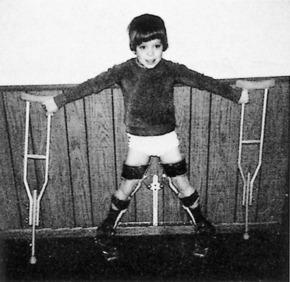

Referral is indicated whenever the diagnosis is suspected. Treatment recommendations continue to evolve. The ultimate goal of treatment is to prevent deformity of the femoral head while healing is progressing. If a deformity can be prevented, the chances of degenerative joint disease developing at a later date are lessened. The initial goals of treatment are the relief of pain and maintenance of joint motion, which are accomplished by rest to control synovitis. Many children younger than 6 years of age with minimal involvement have a good prognosis and require only symptomatic care. The older child who is at risk for having a poor outcome may require treatment. In these children, treatment is aimed at keeping the femoral head centered in the acetabulum. If the head is contained in the acetabulum while it is re-forming, the acetabulum will “mold” the head and prevent significant deformity from occurring. These goals of treatment are usually accomplished by the use of an abduction brace that allows motion but contains the head in the acetabulum (Fig. 10-11). The brace must be worn continuously for up to 2 years, although the results of specific forms of treatment remain inconclusive, and some investigators advocate only nighttime bracing. Surgery may be necessary in select cases.

Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis is a disorder of unknown cause in which weakening of the epiphyseal plate of the upper femur occurs and results in upward and anterior displacement of the femoral neck. The actual amount of displacement varies. In most cases, the slippage is gradual, and some elements of healing are usually present. The condition is seen most commonly in boys between the ages of 11 and 16 years during their rapid growth spurt. The disorder is bilateral in 25% of cases and frequently occurs in two distinct body types. The first is the slender, tall, rapidly growing boy, and the second is the large, obese boy with underdeveloped sexual characteristics. The presence of the disorder in these two body types suggests a hormonal cause, but none has been proved.

CLINICAL FEATURES

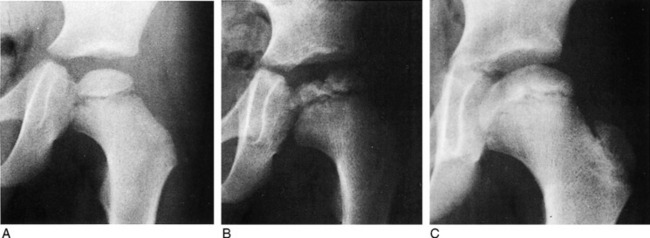

In the early “preslipping” stage, the roentgenogram characteristically reveals irregular widening of the epiphyseal plate and joint swelling (Fig. 10-12). As displacement occurs, a line drawn along the superior or anterior neck of the femur will transect less of the femoral head than normal. This may be more readily seen on the lateral view. More severe degrees of slippage are usually easily diagnosed.

A condition similar to slipped capital femoral epiphysis is termed acute traumatic separation of the upper femoral epiphysis (Fig. 10-13). This is actually an epiphyseal fracture and has a much poorer prognosis than the gradual slippage that occurs in slipped capital femoral epiphysis.

TREATMENT

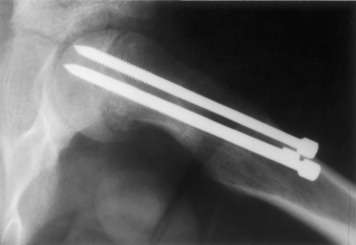

As soon as the diagnosis is made, a referral for surgery is indicated. The patient is immediately placed on crutches, and weight bearing is prohibited. Traction in the hospital may be necessary to reduce the acute component of the slippage. To prevent further slippage from occurring, the femoral head is fixed to the neck, generally by using small pins (Fig. 10-14). Weight bearing is prohibited for several months until the epiphyseal plate closes. Severe deformities may also require osteotomy of the femur.

The prognosis is usually good, except in those cases with acute traumatic separation. The chronic form may result in slight shortening of less than 1.25 cm along with a mild external rotation deformity. In cases with acute traumatic separation, avascular necrosis of the femoral head is a common complication, and this usually results in severe traumatic arthritis of the hip (Fig. 10-15). The more common chronic slippage does not usually cause avascular necrosis.

Transient Synovitis (Irritable Hip)

Septic Arthritis in Childhood

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

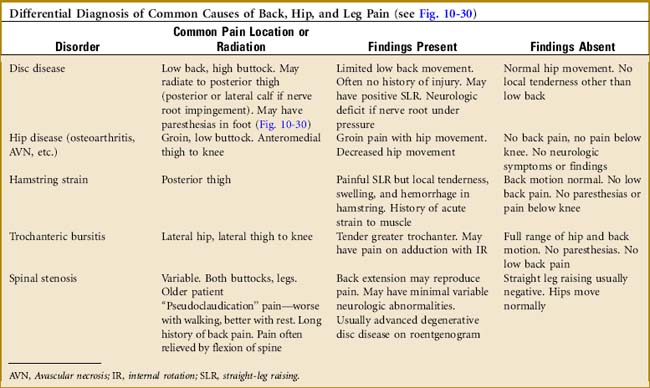

Differentiation of mild cases from transient or rheumatoid synovitis may be difficult. A child with transient or rheumatoid synovitis generally appears well except for the hip, the fever is usually mild; and the hip is more “irritable” than painful. The white blood cell count and sedimentation are only slightly elevated. The hip aspirate may show an increase in white blood cells, especially polymorphonucleocytes, but the Gram stain and culture will be negative. Complete bed rest and symptomatic care usually cause considerable improvement in 24 hours, in contrast to a septic hip, which usually worsens (Table 10-1).

Table 10-1 The Limping Child—Differential Diagnosis of Common Causes*

| Disorder | Symptoms/History | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Congenital dislocated hip | Painless. Usually noticed when child first begins to walk (12–18 mo). May be bilateral | Trendelenburg sign positive. Leg shortened if unilateral. “Telescoping” of leg at hip. Abnormal roentgenogram |

| Perthes’ disease (or other AVN) | Minimal pain (groin, anteromedial thigh) Age 4–8 yr. Family history positive if due to rare sickle cell or other hereditary anemia. No fever | Decreased hip ROM, especially abduction, and IR. Roentgenogram may show early joint widening. Later (2–4 wk) bony changes. Lab values normal (except if due to blood disorder) |

| Transient synovitis | Irritable. Slight fever, groin and anteromedial thigh pain. Age 4–8 yr | Diminished hip movement. Slightly painful with motion. Roentgenogram may show slight joint space widening, fluid. Slight increase in ESR, WBC. Hip aspirate shows increased WBC, no bacteria |

| Septic hip | Painful! Septic, febrile, unable to ambulate. Groin pain (may be difficult to localize findings in young child) | Pain on slightest hip movement. Roentgenogram shows hip joint swelling. Hip aspirate positive for bacteria. Lab reflects infection |

| Slipped upper femoral epiphysis | Age 10–14 yr. Mild ache in groin, thigh. Leg often externally rotated | Limited IR. Roentgenogram shows slippage |

| “Low-grade” osteomyelitis, lower limb. | Fever, irritable. Moderate pain with weight bearing (may be difficult to localize findings in young child) | Local bony tenderness and soft tissue swelling. Protected motion. Early plain roentgenogram normal. Bone scan abnormal |

| Inflammatory joint disease | Single or multiple joints. May be mildly febrile | Joint swelling, heat. Some limitation of motion. Serum studies sometimes abnormal. Often diagnosis of exclusion |

| Neurologic disorders (CP, etc.) | Often bilateral. No pain. Gait may be wide based. Delay in motor development. History of perinatal problems | Abnormal neurologic findings |

AVN, Avascular necrosis; CP, cerebral palsy; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IR, internal rotation; ROM, range of motion; WBC, white blood cell count.

* NOTES: Always consider (1) battered child (especially if history of previous injuries, such as burns), (2) tumor, and (3) occult fractures. When knee pain occurs in children, always evaluate the hips.

Coxa Vara

Coxa vara is an abnormality of the upper portion of the femur that consists of a decrease in the normal angle of inclination below 110 to 125 degrees (Fig. 10-16). This may result from a wide variety of acquired and congenital conditions and usually results in a shortened extremity.

CONGENITAL FORMS

Congenital local disturbances in the growth of the proximal aspect of the femur may also lead to shortening and a significant coxa vara deformity. These disorders usually fall into three distinct classifications: congenital coxa vara, congenital bowed femur with coxa vara, and congenital short femur with coxa vara.

CONGENITAL COXA VARA (INFANTILE, CERVICAL, OR DEVELOPMENTAL)

This disorder is the result of faulty development of the femoral neck, which leads to the varus deformity. The cause is unknown. The disorder is frequently bilateral and becomes manifested after weight bearing has begun. The child usually presents with a painless limp. If the disorder is bilateral, a “duck-waddle” gait may be present. In this gait pattern, the body sways from side to side. Abduction and internal rotation of the affected extremity are usually restricted, and the leg may be from 2.5 to 5 cm shorter than normal. The lumbar lordosis is usually exaggerated, and with continued weight bearing the varus deformity may progress.

Degenerative Arthritis (Osteoarthritis)

CLINICAL FEATURES

The roentgenographic findings are characteristic (Fig. 10-17). Irregular sclerosis, joint space narrowing, and osteophyte formation are prominent features.

TREATMENT

Conservative treatment frequently relieves symptoms and improves motion. The regimen requires a cooperative patient. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen are often helpful, and the joint is unloaded. Weight reduction is recommended when indicated, and the use of a cane is encouraged. The cane is usually used in the hand opposite the affected extremity (although it may be used in the ipsilateral hand), and pressure is applied to the cane at the same time that weight is being borne on the painful hip (see Chapter 18). Moist heat is sometimes helpful. Gentle range-of-motion exercise, such as swimming, will often overcome contractures and restore motion. The treatment plan may have to be repeated at intervals. Intraarticular hip joint injection with steroid is rarely performed because of the relative inaccessibility of the joint.

Avascular Necrosis (Osteonecrosis)

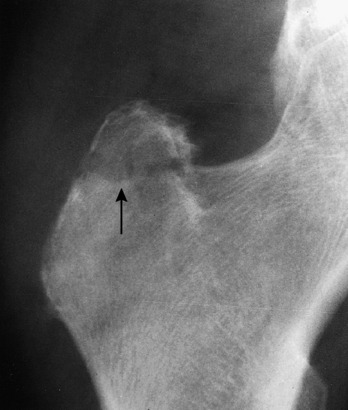

CLINICAL FEATURES

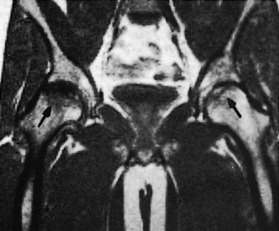

The onset is gradual, with pain and a slight limp being common. A history of trauma is usually absent in the usual idiopathic type. Joint motion becomes progressively restricted, mainly caused by chronic synovitis. The roentgenogram reveals an increase in the density of the superior portion of the femur (Fig. 10-18). A radiolucent zone is frequently present between the avascular segment and the surrounding bone. The joint space is usually well preserved until late in the disease, when collapse of the head occurs, which can cause irregularity and later degenerative arthritis. Avascular necrosis is one of the main indications for MRI, which usually reveals the lesion quite clearly (Fig. 10-19).

TREATMENT

The goal of treatment is to prevent collapse of the femoral head and encourage repair of the necrotic area. With minimal involvement, prolonged abstinence from weight bearing by the use of crutches may allow regen eration of the avascular segment, although considerable time is required. Later in the disease, when collapse has occurred, prosthetic replacement is indicated.

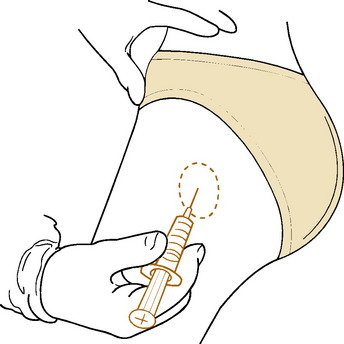

Bursitis

Treatment consists of moist heat, rest, and anti-inflammatory agents. Ultrasound to the affected area may be beneficial, and a local injection of a steroid/lidocaine mixture into the area of maximum tenderness is frequently curative (Fig. 10-20). Surgery is not helpful.

Meralgia Paresthetica

Meralgia paresthetica is a common disorder characterized by pain and paresthesias occurring along the course of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh. This nerve enters the leg beneath the inguinal ligament 1 cm?medial to the anterior superior iliac spine and supplies sensation to the anterolateral aspect of the thigh (Fig. 10-21). Painful involvement of the nerve may be confused with hip and low back disorders. The cause of this condition is unknown, but direct pressure or constriction of the nerve at its point of exit into the thigh is thought to play a role. The condition is more common in joggers and gymnasts (possibly as a result of repeated excessive hip extension exercises). Rarely, the disorder can be traced to an intraabdominal or pelvic mass (because of the retroperitoneal course of the nerve). The condition may also be confused with an L3–L4 disc problem.

Protrusio Acetabuli (Otto Pelvis)

CLINICAL FEATURES

The onset is usually gradual, with progressive restriction of hip motion occurring over several years. Eventually, pain becomes a prominent symptom. Complete ankylosis of the joint frequently occurs. The roentgenogram reveals abnormal protrusion of the medial wall of the acetabulum with thinning and degenerative changes (Fig. 10-22). The underlying disorder may also be noted.

Dislocations of the Hip

Dislocations of the hip are the result of severe trauma and are usually posterior in direction (Fig. 10-23). They commonly result from the knee being struck while the hip and the knee are in a flexed position. This force drives the femoral head out of the joint posteriorly. These injuries are frequently associated with fractures of the posterior acetabular wall. Anterior dislocations are less common and usually result from a force on the knee with the thigh abducted. The neck of the femur impinges on the posterior rim of the acetabulum, and the head is levered out the front.

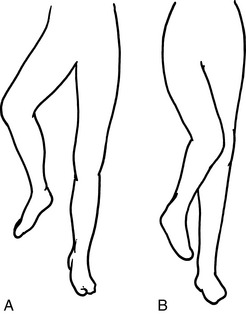

CLINICAL FEATURES

With posterior dislocation, the hip is characteristically held in a position of flexion and internal rotation (Fig. 10-24). All motions are painful. There may be an associated injury of the ipsilateral knee. In anterior dislocations the leg usually rests in external rotation.

Fractures of the Hip

Intracapsular and intertrochanteric fractures are both common in the older patient and usually result from a fall on the hip. Both fractures are characterized by shortening and external rotation of the affected leg with pain in the region of the hip joint (Fig. 10-25). Osteoporosis clearly plays a significant role (see Chapter 8). Occasionally, the patient may actually fracture the femoral neck before falling, the fracture representing the completion of an insufficiency injury. Femoral neck fractures may also be occult and show up only with repeated examinations, bone scan, or MRI.

TREATMENT

The objective of management is the return to the pre-injury level of function as soon as possible. If external immobilization or prolonged bed rest were required in the treatment of these fractures in this age group, the mortality would be high because of pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, and urinary tract infections. For this reason, early surgery (within 24–48 hours) is indicated to allow the patient to be out of bed at the earliest possible time. Displaced intracapsular fractures in the elderly are best treated by early prosthetic replacement (Fig. 10-26). This allows early weight bearing and eliminates the possibility of nonunion and avascular necrosis that could necessitate secondary surgical procedures. (If osteoarthritis is present, total hip replacement is often performed.) Undisplaced or impacted fractures are often treated nonoperatively or by simple internal fixation to add stability. These fractures have a much better prognosis regarding healing and avascular necrosis. Patients with fractures from low trauma events (sometimes called fragility fractures) should be evaluated for osteoporosis.

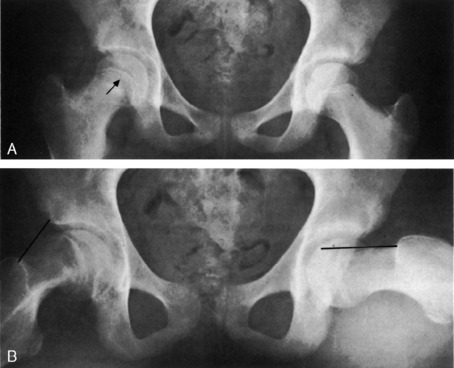

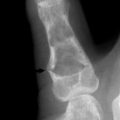

Intertrochanteric fractures are treated by open reduction and internal fixation (Fig. 10-27). This allows early activity by eliminating the pain at the fracture site. Nonunion in this fracture is much less common than with the intracapsular fracture. Weight bearing is usually restricted for several weeks until union of the fracture has occurred, however.

Fig. 10-27 A, Intertrochanteric fracture of the hip. B, Following open reduction and internal fixation.

Nonsurgical treatment

Intertrochanteric and intracapsular fractures occasionally occur in nonambulatory patients, sometimes as a result of a fall during a transfer. These fractures are often treated nonsurgically. Early bed-to-chair mobilization and vigilant nursing care are important to prevent complications. The fracture usually becomes pain-free in a short time, and even if solid bony healing does not occur, a painless fibrous union develops with a satisfactory end result.

Occasionally, an isolated fracture of either trochanter may occur following a minor injury (Fig. 10-28). Treatment is symptomatic, with crutches and weight-bearing activity as tolerated.

THE OCCULT HIP FRACTURE

If the diagnosis is suspected, the patient should be admitted to the hospital and placed on non–weight-bearing status to prevent displacement of the fracture in case one is present. Bone scanning is helpful (Fig. 10-29). It may show evidence of the fracture as early as 24 hours but is often not diagnostic until 48 to 72 hours. MRI is also helpful, and although more costly, it can allow more early diagnosis and treatment. Computed tomographic scanning is also helpful. Treatment is usually surgical for femoral neck fractures to prevent displacement that could require a more complicated operation.

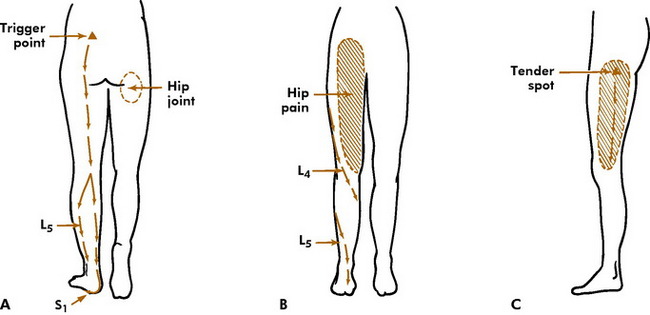

Fig. 10-30 A, Typical lumbar disc pain when herniation is far enough to cause radicular (L5 or S1) pain. If herniation is minor, only unilateral low back pain may occur. B, Anterior distribution of hip joint pain. (Hip disease may also cause low buttock pain.) Also shown are nerve roots L4 and L5. C, Pain distribution of trochanteric bursitis. NOTE: Calf or general leg symptoms may be the first and only sign of lumbar disc herniation with radiation. Chronic “hamstring” pain lasting longer than 3 to 4 weeks, especially in the absence of an obvious injury, should suggest a radiculopathy.

Aegerter E, Kirkpatrick JA. Orthopedic diseases, ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1968.

Allen WC, Cope R. Coxa saltans: the snapping hip revisited. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:303-308.

Bowen JR, Foster BK, Hartzell CR. Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease. Clin Orthop. 1984;185:97-108.

Cattaral A. The natural history of Perthes’ disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1971;53:37-53.

Friedenberg ZB. Protrusio acetabuli. Am J Surg. 1953;85:764-770.

Grant JCB. A method of anatomy, ed 6. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1958.

Hermel MB, Albert SM. Transient synovitis of the hip. Clin Orthop. 1962;22:21-26.

Meyers MH. Fractures of the hip. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers, 1985.

Scherl SA. Common lower extremity problems in children. Pediatr Rev. 2004;25:52-62.

Skaggs DL, Tolo VT. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1996;4:9-16.

Somerville EW. Perthes’ disease of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1971;53:639-649.

Sorbie C. Arthroplasty in the treatment of subcapital hip fracture. Orthopedics. 2003;26:337-341.

Stewart MJ, Milford LW. Fracture-dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36:315-342.

Swiontkowski MF. Intracapsular fractures of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:129-138.

Tachdjian MO. Pediatric orthopedics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1972.

Teasdall RD, Webb LX. Innovations in the management of hip fractures. Orthopedics. 2003;26:843.

Webb LX. Proximal femoral fractures. J South Orthop Assoc. 2002;11:203-212.