CHAPTER 5 THE ROLE OF TRAUMA PREVENTION IN REDUCING INTERPERSONAL VIOLENCE

The issue of interpersonal violence as a public health problem gained a significant national spotlight through a workshop in October 1985 convened by the Surgeon General of the United States to address the problem.1 A challenge went out to health care providers, administrators, and the public at large to consider violence as a public health problem, and to seek its causes and most effective treatment. In the ensuing 2 years, more Americans died from gunshot wounds than during the entire 8-½ years of war in Vietnam. By 1994, intentional injury was the 10th leading cause of death in America (20,000 per year) and the leading cause of premature mortality.2

UNDERSTANDING THE PROBLEM

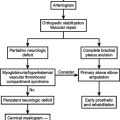

Although the American College of Surgeons requires that a Level I trauma center be actively involved in injury control, the trauma surgeon dealing with resuscitation, operative intervention, and postoperative critical care requires guidance from a vast array of professionals to understand and prevent injuries due to interpersonal violence.3 In 1991, Rosenburg and Mercy wrote, “Professionals from sociology, criminology, economics, law, public policy, psychology, anthropology, and public health must work together to understand the cause and solution” to the problem of intentional injuries. Intervention against intentional injuries requires consideration of the perpetrators, the victims, the assaulting weapons, and the environment and the circumstances of the event.

IMPACT OF ENHANCED TRAUMA COMMITMENT ON PATIENT OUTCOMES

The result of several studies from the Division of Trauma at Johns Hopkins Hospital suggested the importance of violence prevention as the avenue for additional improvement in trauma patient outcome. It began with a study showing that, while the implementation of a multidisciplinary trauma program resulted in significant improvement in patient outcomes, no improvement was seen among patients with gunshot wounds, the majority of whom were youths (ages 15–24).4 This observation was explained by a disturbing pattern showing an increasing prevalence of gunshot-wound patients arriving “in extremis” or dead on arrival (DOA) from multiple gunshot wounds to the head and/or chest. While 99% of patients leaving the emergency department (ED) alive ultimately survived their hospital visit, the ever-growing incidence of patients who are DOA suggests that the “glass ceiling” is being approached in terms of benefits in patient outcomes to be gained from in-hospital performance improvement endeavors. In 2005, 61 of the 88 trauma deaths (69%) seen at Johns Hopkins Hospital were declared dead in the ED in an average 6 minutes after arrival. Of the remaining 27 patients, 14 were declared dead in the intensive care unit from devastating brain injuries. This suggests that in an entire calendar year, at an urban, university-affiliated Level I trauma center, only 13 of 88 patients who died (15%) were even theoretically salvageable. This is perhaps the most compelling argument suggesting that further incremental improvement in injury outcomes are likely to be realized from prevention activities in the prehospital arena.

A second study involved a geographic analysis showing that the majority of trauma patients admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital came from a 5-mile radius, incorporating some of Maryland’s most impoverished neighborhoods, and confirmed the previously described predominance of youths (ages 15–24) among gunshot wound patients.5 These data led to the conclusion that the injury prevention program should take the form of violence prevention activities for at-risk youths.

IN-HOSPITAL PREVENTION: SHORTCOMINGS

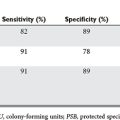

A third project sought to duplicate the experience with alcohol- and drug-abuse intervention described at other centers among predominantly blunt trauma populations.6 Given the recognized comorbid incidence of alcohol and substance abuse among perpetrators and victims of interpersonal violence, a project was undertaken that sought to analyze introspection and readiness to change among young patients (ages 15–24) surviving an injury and demonstrating a positive toxicology screen. In contrast to other reports in the literature, this project demonstrated a depressingly low incidence of “readiness to change,” and an even lower incidence in accessing available counseling services. This study suggests a major shortcoming of an in-hospital violence prevention program: The potential beneficiaries are random and are based on the trajectory of a bullet, rather than the presence of psychosocial risk factors.

EFFECTIVENESS OF A VIOLENCE PREVENTION PROGRAM

Baltimore is one of the most appropriate cities in America in which to pursue initiatives in youth violence prevention. It is the nation’s 13th largest city, and the largest American city that did not enjoy the decrease in violence seen nationally in the mid-1990s. Baltimore ranks at or near the top of the nation in the following high-risk indicators: (1) rate of births to unwed teenage mothers, (2) episodes of assault and suspension among students in Baltimore City Elementary Schools (K–5), (3) dropout rate for Baltimore City Public High Schools (76% for black males), and (4) juvenile arrest rate for murder.

A project was undertaken evaluating the effectiveness of a violence-prevention initiative geared toward changing attitudes about interpersonal conflict among at-risk youths from a previously described catchment area.7 Participants were given a package survey of six previously validated scales, both preintervention and postintervention, to assess their attitudes about interpersonal conflicts. This package included the following scales:

1 CE Koop, ML Rosenberg & JA Mercy, et al: Violence as a Public Health Problem. Background papers prepared for the Surgeon General’s Workshop on Violence and Public Health, October 27–29, 1985, Leesburg, VA. Atlanta, GA, Violence Epidemiology Branch, Center for Health Promotion and Education, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1985

2 Koop CE, Lundberg GD. Violence in America: a public health emergency. JAMA. 1996;267(22):3075.

3 Cornwell EEIII, Jacobs D, Walker M, et al. National Medical Association Surgical Section position paper on violence prevention: a resolution of trauma surgeons caring for victims of violence. JAMA. 1995;273:1788.

4 Cornwell EE, Chang DC, Phillips J, Campbell KA. Enhanced trauma program commitment at a Level I trauma center: impact on the process and outcome of care. Arch Surg. 2003;138(8):838-843.

5 Chang DC, Cornwell EE, Phillips J, Baker D, Yonas M, et al. Community characteristics and demographic information as determinants for a hospital-based injury prevention outreach. Arch Surg. 2003;138(12):1344-1346.

6 Yonas M, Baker D, Cornwell EE, Chang DC, Phillips J, et al. Inpatient counseling for alcohol/substance abusing youths with major Trauma. Ready or not? J Trauma. 2005;59(2):466-469.

7 Chang DC, Sutton ER, Cornwell EE, Allen F, Yonas M, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of a multi-disciplinary youth violence prevention initiative: changing attitudes regarding interpersonal conflict? J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(5):721-723.