19 The Role of Spinal Injections in Treating the Aging Spine

KEY POINTS

The use of invasive procedures for spinal conditions has proliferated over the years, particularly with the advent of fluoroscopic guidance. The most common spinal targets for injection are the epidural space, nerve root sheath, facet joints, and the sacroiliac joints. There is much controversy regarding the utility of these injections, however, both as diagnostic and as therapeutic tools. For the surgeon, diagnostic considerations are important for determining a true “pain generator” before offering specific surgical recommendations. This is vitally important because history, physical exam, and imaging studies are often limited in specificity for individual pain conditions.1,2 The therapeutic value of interventions is important as an adjunct to other nonsurgical treatments, particularly to help patients avoid surgery or to alleviate pain in patients who are otherwise poor surgical candidates.

Modern guidelines and recommendations from various societies suggest that the use of fluoroscopic (or CT) guidance is mandatory (when not contraindicated) to improve the accuracy and safety of these procedures.1,2 Although ultrasound guidance has been explored, this modality is limited in its ability to detect intravascular uptake.3 Despite “blind” techniques being described for all types of injections, the only ones that may be done without image guidance with any acceptable chance of safe, proper needle placement include lumbar interlaminar and caudal epidural steroid injections (ESIs).

Contraindications to steroid injections (and other invasive spinal procedures) include bleeding diathesis, anticoagulation, local or systemic infection, uncontrolled diabetes or glaucoma, hypovolemia, and medical instability; and high doses of local anesthetics should be avoided in patients with multiple sclerosis.1 Acute fracture and malignancy should also be avoided. Contraindications to fluoroscopy include pregnancy.

Epidural Steroid Injections

A recent systematic review of relevant ESI literature by Salahadin et al.4 highlights the variability in quality and relevance of studies looking at ESI efficacy. A common pitfall when studying invasive procedures is considering the efficacy of the comparator procedure. For instance, many studies evaluating ESI compare the procedure to epidural saline,5 epidural anesthetic without steroid,6 injections into nearby tissues,7 alternative injected medications (e.g., hyaluronic acid and Sarapin) or a combination of these strategies.8,9 Many of these comparator procedures have demonstrated therapeutic efficacy and are therefore not truly placebo. Matthews et al.7 compared caudal ESIs to local anesthesia over the sacral hiatus (some were at “tender spots,” however). This may be most consistent with a true placebo comparator.

Considering the proposed mechanism of action of steroid injections (reducing inflammatory chemicals at the site of injury/pathology and possibly contributing to neuronal stability), the expectation that any type of steroid injection, done one time, will result in more than 6 months of relief or benefit is unrealistic.1 Therefore the number and frequency of injections are other variables that must be considered when assessing the long-term efficacy of injections.1,10 Consistency of outcome measures must also be considered: improvement in both reported pain and functional ability should be considered when judging the efficacy of any procedure, including ESI.

In their review, Salahadin and colleagues4 considered anything less than 6 weeks as “short term” and any time beyond 6 weeks as “long term.” Their analysis, using commonly accepted “evidence-based medicine” definitions for literature review, yielded ratings for each approach as outlined in Table 19-1. Interlaminar and transforaminal ESIs in the low back and neck had “indeterminate” evidence for use in axial spine pain, postlaminectomy syndrome, lumbar disc extrusions, and lumbar stenosis. Interestingly, caudal ESIs have “moderate” evidence for short- and long-term improvement for chronic, axial low back pain, and their “strong” and “moderate” short- and long-term ratings for radicular pain also include patients with postlaminectomy syndrome.4

TABLE 19-1 Summary of Literature Support for Various ESI Approaches for the Treatment of Lumbar and Cervical “Radicular Pain” as Outlined by Salahadin et al.4

| Short-term Benefit | Long-term Benefit | |

|---|---|---|

| Lumbar interlaminar ESI | Strong | Indeterminate |

| Lumbar transforaminal/SNRB | Strong | Moderate |

| Caudal ESI | Strong | Moderate |

| Cervical interlaminar ESI | Moderate | Moderate |

| Cervical transforaminal/SNRB | Moderate | Moderate |

From the surgeon’s standpoint, avoidance of surgery is an important outcome consideration. In this regard, at least transforaminal injections (lumbar and cervical) have shown efficacy.11 This approach, in the lumbar spine, has also been shown to be more effective for radicular pain than interlaminar ESIs.

There is no significant evidence to suggest a specific, fixed timing regimen of injections. Current guideline recommendations (including Official Disability Guidelines and International Spine Intervention Society[ISIS]) suggest that repeated injections should be considered as symptoms recur, and the repeated injections should not be considered in patients who do not demonstrate significant (usually defined as >50% short-term relief) transient improvement following an initial injection. Similarly, the maximum number of injections that an individual may undergo during a specific amount of time (such as during 1 year) has not been adequately studied, but consensuses from various guidelines and societies suggest that no more than four injections should be considered over the course of a year and that repeated injections should be separated by at least one to two weeks. Riew et al.6 found that up to four lumbar transforaminal ESIs were required to optimize therapeutic benefit (in this case, avoidance of surgery) beyond 15 months, and the interval between injections ranged from 6 days to 10.5 months. This is also the only lumbar injection study12 to require a failure of 6 weeks of other nonoperative interventions including physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), bracing, or a combination of the three. The integration of these other treatments with injection therapies is therefore also poorly understood.

Complications of epidural injections include generic considerations for any invasive procedure (local tissue trauma, bruising, pain, infection) as well as those specific for trauma to the local spinal tissues, medication or steroid related side effects, and those associated with x-ray exposure during fluoroscopy. Minor complications including dural puncture with subsequent “spinal headache,” increased pain, elevated blood sugar level or blood pressure, sympathetic mediated symptoms such as flushing or vasovagal response and acute insomnia have been described and occur infrequently. Botwin et al reported an overall complication rate during fluoroscopically guided ESIs as occurring in less than 10% for lumbar injections13 and approaching 17% for cervical ESIs.14 Caudal injections had a rate of minor complications of 15.6%,15 and for the thoracic spine, a 20.5% rate was reported.16 Intravascular needle placement has been noted in about 10% to 20% of lumbar injections.17 Subarachnoid needle placement is also a concern, because it may cause spinal anesthesia or arachnoiditis.1

Major or severe complications are fortunately very rare when injections are performed with fluoroscopy and by experienced interventionalists.1 Potentially catastrophic injury can occur, however, including infarction of central nervous system tissues (causing paraplegia, tetraplegia, or stroke syndromes), compression of neural elements or spinal cord by hematoma, CNS infections, pneumocephalus, and chemical meningitis, to list a few. Transforaminal approaches, particularly in the cervical spine, likely carry the greatest risk of these rare yet serious complications.4

Predictors for negative outcome following ESI include poor education, unemployed status, smoking, chronic or constant pain, high medication usage, high number of previously attempted treatments, pain that is not increased with activity or coughing, psychological disturbances, and nonradicular diagnoses.18

Facet Joint Procedures

Approximately 20% of low back pain complaints can be attributed to the zygapophyseal joints in the lumbar spine1,19–22 and likely account for even higher rates of pain in the cervical and thoracic spines.19,20,22 Also known as facet or z-joints, these joints become arthritic and potentially painful as with any joint in the body, and consequently, older individuals may be expected to be more likely to respond to facet blocks than younger patients.20,21,23 In fact, in a study of older Australians with non–injury-related chronic low back pain, 30% of individuals reported at least 90% relief following placebo-controlled facet blocks.21

Over the past 40 years, our understanding of the innervation of facet joints and their potential as pain generators has greatly expanded.2 We now know that even referred leg pain and hamstring tightness can be associated with facet joint pain and thus mimic features of sciatica. Cervical facet joints may refer pain to the head, neck, and shoulder areas and have well- described referral pattern “maps,” whereas thoracic facet joints may produce mid back pain with accompanying neuropathic symptoms as well.22 Along with the evolution of this knowledge, so too have interventional approaches in dealing with facet-mediated pain.

The specific diagnosis of facet-mediated pain is difficult and controversial, however, because there are no reliable factors of patients’ history, physical exam, or imaging studies to otherwise effectively determine pain of facet origin. Several studies have evaluated the use of single photon emission CT (SPECT) to determine if abnormalities can predict facet joint disease and therefore predict favorable response to joint injections. One study example by Pneumaticos et al24 determined that patients who had “hot” facet joints treated with steroid injection responded more favorably than patients who also had non–hot joints injected (joints were selected clinically by the attending physician as is done in typical practice). Despite this and other positive results, SPECT is not routinely used, perhaps because of limited availability and expense.

For diagnostic injections, there is a high false-positive rate for single sets of lumbar injections.19 Therefore two positive diagnostic injections are felt to be required before considering pain to be truly of facet origin, at least for the purposes of clinical research. These injections should be low volume and demonstrate a specific response based upon the expected duration of the anesthetic used.23,25 In clinical practice, this “double block” approach may not required, or practical, given the relatively similar morbidity of rhizotomy (the procedure that should be considered if diagnostic blocks are positive) compared to injections. Others also argue that the improved specificity of double blocks reduces the sensitivity and therefore denies a potentially therapeutic procedure (rhizotomy) to some patients who would otherwise benefit. Again, this approach assumes that the risks and comorbidity of performing rhizotomy in patients with false-positive results is not significantly greater than performing the second diagnostic block.

Potential complications of facet joint procedures include those described in the section on ESI that may be related to needle placement; side effects of sedation, injected medication, or both; and radiation associated with image guidance.22 Septic joints have been reported after intraarticular injections,26 whereas radiofrequency (RF) neurotomy procedures have been associated with painful dysesthesia, anesthesia dolorosa, hyperesthesia, and nerve root injury22; however, the overall rate of even minor complications is very low.27

Over the years, conflicting results have emerged regarding efficacy of facet joint procedures.22 One of the most recent systematic reviews by Bogduk et al 2 only considered prospective, double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials in their evaluation, and determined that controlled, diagnostic medial branch blocks are the only validated method of diagnosing facet mediated pain and that properly performed neurotomy is the only validated treatment for facet joint pain. A more encompassing review was done by Boswell et al.,22 and their results are included in Table 19–2. Their process was similar to the Salahadin et al. review discussed in the section on ESI,4 and short-term and long-term relief were defined as 6 weeks or less versus longer than 6 weeks duration for injections, respectively, and less than or more than 3 months duration, respectively, for neurotomy procedures. Of note, achievement of long-term relief with injection therapy often requires multiple injections. For instance, in their study of cervical facet pain, Manchikanti et al.28 noted an average of 3.5 injections over the course of a year with an average duration of effect of approximately 3.5 months per injection. Interestingly, this benefit of medial branch blocks was noted with or without steroid. Findings, including number of injections and duration of effect, were similar in their studies of lumbar and thoracic medial branch blocks as well.29

TABLE 19-2 Summary of Literature Support for Various Facet Joint Procedures for the Treatment of Chronic Facetogenic Pain as Outlined by Boswell et al22

| Procedure | Short-term Relief | Long-term Relief |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical intra-articular | Limited | Limited |

| Thoracic intra-articular | Indeterminate | Indeterminate |

| Lumbar intra-articular | Moderate | Moderate |

| Cervical MBB | Moderate | Moderate |

| Thoracic MBB | Moderate | Moderate |

| Lumbar MBB | Moderate | Moderate |

| Cervical MBN | Strong | Moderate (Strong∗) |

| Thoracic MBN | Indeterminate | Indeterminate |

| Lumbar MBN | Strong | Moderate |

∗ Long-term relief for cervical facet pain has strong evidence when a multiple lesion per level strategy is used, as reported by Lord et al and advocated by others.23,35 This procedure is not commonly done in the United States and significantly increases operative time.

Medial branch blocks (MBB) in the lumbar spine have been repeatedly validated for diagnostic utility.2 ISIS guidelines23 suggest that patients should be evaluated for at least 2 hours postinjection, or until relief ceases (whichever occurs first). To be truly diagnostic, relief should also be noted while the patient is attempting activities that are typically aggravating. There is debate regarding the amount of relief required to consider blocks successful,2,20 but 80% pain relief has typically been accepted as the standard for a “positive” response. A recent retrospective study by Cohen et al.20 however, indicates that the patients who reported 50% to 79% improvement following a single diagnostic block did as well with subsequent rhizotomy as those who reported 80% or more relief following diagnostic block. It is also unclear how much secondary factors, including the use of sedation, anesthesia, or both, during diagnostic blocks, affect the results.20

The use of steroids and Sarapin have also been studied for medial branch blockade both in the neck and low back. These substances have not demonstrated improved or longer lasting efficacy as compared to bupivacaine alone in subjects identified as having facet-mediated pain with double blocks.28,29

Intraarticular steroid injections have been shown to be no more effective than saline injections into the facet joints.26,30 Unfortunately the only prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial for intraarticular cervical facet injections was limited to MVC-related whiplash sufferers.30 The authors screened patients for facet-mediated pain with double blocks and found no benefit from intraarticular steroid versus anesthetic. Results of this study, however, should not be applied to degenerative cervical facetogenic pain, which should be studied separately. A study by Kim et al.31 evaluated intraarticular cervical facet injections in a variety of diagnoses and found that those with “disc herniation” responded better than those with myofascial or whiplash pain syndromes. Intraarticular hyaluronic acid injections were compared to lumbar facet joint steroid injections by Fuchs et al,32 and no difference in efficacy was noted.

Radiofrequency neurotomy of the medial branch nerves (MBN) (and dorsal ramus of L5) has been used extensively to denervate suspected painful facet joints and remains the only available intervention that has demonstrated substantial, long-term relief.2 Early techniques, where an RF probe is placed perpendicular to the path of the target nerve, have been criticized and often demonstrate limited efficacy.2 The more modern approach of placing the probe along the length of the suspected nerve path is recommended by the International Spine Intervention Society23 and has been shown to coagulate a greater length of the target nerves. Because repairing a greater length of nerve will take longer than a shorter lesion, it can be expected that the “parallel probe” technique can result in long-lasting improvement, as has been suggested in reviews of these techniques and studies.2 With parallel probe placement, significant benefit (60%-80% improvement) may last 6 to 12 months or even longer.33 Benefit has also been demonstrated with up to three repeated treatments, and no limit has yet been established as to how many treatments may result in diminished returns.33 Usual RF ablation involves lesioning at 80° C for 90 seconds at each site, but benefit has also been demonstrated with “pulsed” RF current at 2 Hz for 4 minutes at 42° C.34

In the cervical spine, one prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial has been conducted for assessing medial branch neurotomy.35 The authors determined that this treatment is effective in patients who have MVC-related whiplash with demonstrated facet pain (at C3-C4 and C6-C7) using a triple block technique. This technique is similar to the aforementioned double block, with the addition of a single placebo block as well.

When done according to recommended ISIS guidelines,23 no significant complications of lumbar medial branch neurotomy have been described.2 Debate exists as to whether it is acceptable to perform the procedure under general anesthesia. This may increase the risk of nerve root injury with improper probe placement, because the patient cannot sense and thus warn of impending injury.2 Testing the probe with varied frequency stimulation is important to perform regardless of use of general anesthesia. This allows the interventionalist to assess for motor activation of the nerve root, an important warning sign of probe misplacement.

Other studies have evaluated alternative means for neurotomy, including cryoneurolysis36 and percutaneous laser denervation.37 All three studies have shown promising initial results for short- and long-term relief when performed in the lumbar spine and may become more widespread options in the future.

Sacroiliac Joint Procedures

Similar to facet joints, up to 20% of low back pain complaints can be attributed to the sacroiliac (SI) joint.1,38 The sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic blocks, however, remain controversial because of insufficient study and high false positive rates.38 Similarly, the only prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial involving SI joint injections involved 10 patients with low back pain and spondylarthropathy, and they did not use diagnostic blocks to screen patients. This study39 compared intraarticular injections of steroid versus saline and revealed statistically significant benefit of steroid at 1 month.

Various radiofrequency denervation techniques have been described for the SI joint, but little high-quality evidence exists to support their use. A recent study by Cohen et al.40 describes a novel “cooled-probe” RF denervation technique of the lateral branches as they exit the upper sacral foramen (instead of along the SI joint line, as is done in traditional techniques). The benefit of the cooled RF lesion is that a larger “sphere” of tissue may be lesioned, theoretically improving the chances that the desired nerve branch may be included in the lesioned area. The results of the study demonstrate greater than 50% pain relief, and significant functional improvement, in the majority of patients at 6 months compared to only 14% of patients receiving a sham treatment. Results were similar, however, at 1 month between the two groups. Further study is obviously needed before more widespread acceptance (and coverage) of this technology is seen.

Specific Degenerative Conditions

Degenerative Disc Disease

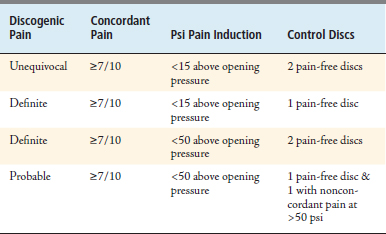

Approximately 40% of low back pain can be attributed to internal disc disruption1; however, there is controversy in this diagnosis because there is no universally accepted gold standard diagnostic test for discogenic pain. When strict interpretive criteria41 are used (Table 19–3), however, discography has proven itself useful in identifying patients who benefit from treatment.42 Not all degenerative discs are painful, however, and it is typical for sufferers of degenerative discogenic pain to have worse complaints during the early or middle stages of degeneration (typically 4th-6th decades) followed by relative pain relief in later years when degenerative pathology is most severe. Painful degenerative lumbar discs are noted to have higher concentrations (relative to nonpainful discs) of sensory fibers at the endplates and nucleus and have higher concentrations of proinflammatory chemicals.1 For this reason, it makes sense to consider local injection of steroid for therapeutic effect, either within or just posterior to the annulus. Transforaminal lumbar ESIs have demonstrated excellent delivery to the anterior epidural space, whereas lumbar interlaminar ESIs achieve ventral flow in just over one third of attempts, and caudal ESIs have significantly variable delivery locations.43

TABLE 19-3 International Spine Intervention Society Guidelines for Discography Interpretation, 200423

Intradiscal procedures such as intradiscal electrothermal therapy (IDET) and percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy of the ramus communicans have shown modest benefit at 6 and 4 months (respectively) in carefully selected patients. Intradiscal steroid injections have very limited data and have not been shown to be more effective than intradiscal saline or bupivacaine injections.44

As discussed in the ESI section, only caudal ESIs have been studied sufficiently and demonstrated some benefit for axial LBP; however, a study by Manchikanti et al.45 revealed no difference in the improvement between discogram positive or negative patients. Although not well studied for axial low back pain, because of their superior placement of medication in the ventral epidural space, a trial of one to three transforaminal ESIs may be considered for discogenic spine pain before consideration of surgery.1

Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis

A recent (2008) literature review that yielded clinical guidelines regarding lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis from the North American Spine Society (NASS),46 found a paucity of evidence to make any recommendations regarding such procedures in this setting. Unfortunately, the same was true for all usual nonsurgical treatments including physical therapy, manipulation, bracing, TENS, or medications. Many of the studies to date have compared “conservative” care to surgical interventions, but there have not been any studies comparing injections to placebo. This includes the recent SPORT study, which has provided significant evidence regarding surgery for the condition.47 Furthermore, data are lacking to accurately describe the natural course of spondylolisthesis.

Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

As with spondylolisthesis, many studies have concentrated on comparing conservative care with surgical intervention, including the recent SPORT study.48 In 2007, clinical guidelines regarding degenerative spinal stenosis were also developed by NASS.49 This group’s review of the available literature led to a Grade B recommendation in favor of a single transforaminal ESI for short-term relief of radicular symptoms associated with stenosis. A Grade C recommendation was made for multiple transforaminal or caudal ESIs to prolong pain relief from radiculopathy or neurogenic claudication associated with spinal stenosis. It should be noted that “multiple” in this setting refers to repeated injections at times when the patient’s symptoms return or worsen following initial injection(s). This is in contrast to previously described “series of 3” injections in which the intervention is repeated at specified time intervals regardless of initial response. This approach had been used extensively in the past when most injections were done without image guidance in order to improve the rate of success. As discussed earlier in the chapter, a fixed schedule for a series of 3 is no longer considered standard of care and is not supported by the literature.

1. DePalma, et al. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with epidural steroid injections. Spine J. 2008;8:45-55.

2. Bogduk N. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with facet injections and radiofrequency neurotomy. Spine J. 2008;8:56-64.

3. Galiano, et al. Real-time sonographic imaging for periradicular injections in the lumbar spine: a sonographic anatomic study of a new technique, J. Ultrasound Med, 24:33-38, 2005.

4. Salahadin, et al. Epidural steroids in the management of chronic spinal pain: a systematic review. Pain Physician. 2007;10:185-212.

5. Karppinen, et al. Periradicular infiltration for sciatica. Spine. 2001;26:1059-1067.

6. Riew, et al. The effect of nerve-root injections on the need for operative treatment of lumbar radicular pain. J Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2000;82:1589-1593.

7. Matthews, et al. Back pain and sciatica: controlled trials of manipulation, traction, sclerosant and epidural injections. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1987;26:416-423.

8. Devulder, et al. Nerve root sleeve injections in patients with failed back surgery syndrome: a comparison of three solutions. Clin. J. Pain. 1999;15:132-135.

9. Manchikanti, et al. Caudal epidural injections with sarapin steroids in chonic low back pain. Pain Physician. 2001;4:322-335.

10. Kolstad, et al. Transforaminal steroid injections in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy: a prospective outcome study. Acta Neurochir. (Wien). 2005;147:1065-1070.

11. Butterman G.R: Treatment of lumbar disc herniation: epidural steroid injection compared with discectomy: a prospective, randomized study, J. Bone Joint Surg. Am, 86-A:670-679, 2004.

12. DePalma, et al. A critical appraisal for the evidence for selective nerve root injection in the treatment of lumbosacral radiculopathy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005;86:1477-1482.

13. Botwin, et al. Complications of fluoroscopically guided transforaminal lumbar epidural injections. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000;81:1045-1050.

14. Botwin, et al. Complications of fluoroscopically guided interlaminar cervical epidural injections. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2003;84:627-633.

15. Botwin, et al. Complications of fluoroscopically guided caudal epidural injections. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2001;80:416-424.

16. Botwin, et al. Adverse effects of fluoroscopically guided interlaminar thoracic epidural injections. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2006;85:14-23.

17. Furman, et al. Incidence of intravascular penetration in transforaminal lumbosacral epidural steroid injections. Spine. 2000;25:2628-2632.

18. Hopwood, et al. Factors associated with failure of lumbar epidural steroids. Reg. Anesth. 1993;18:238-243.

19. Manchukonda, et al. Facet joint pain in chronic spinal pain: an evaluation of prevalence and false-positive rate of diagnostic blocks. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2007;20:539-545.

20. Cohen, et al. Lumbar zygapophyseal (facet) joint radiofrequency denervation success as a function of pain relief during diagnostic medial branch blocks: a multicenter analysis. Spine J. 2008;8:498-504.

21. Schwarzer, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of lumbar zygapophyseal joint pain: a study in an Australian population with chronic low back pain, Ann. Rheum. Dis, 54:100-106, 1995.

22. Boswell, et al. A systematic review of therapeutic facet joint interventions in chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician. 2007;10:229-253.

23. Bogduk, et al., International Spine Intervention Society Practice Guidelines for spinal diagnostic and treatment procedures, 1st ed., San Francisco, 2004.

24. Pneumaticos, et al. Low back pain: prediction of short-term outcome of facet joint injection with bone scintigraphy. Radiology. 2006;238(2):693-698.

25. Bogduk N. Diagnostic nerve blocks in chronic pain. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2002;16:565-578.

26. Lilius, et al. Lumbar facet joint syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71B:681-684.

27. Kornick, et al. Complications of lumbar facet radiofrequency denervation. Spine. 2004;29:1352-1354.

28. Manchikanti, et al. Therapeutic cervical medial branch blocks in managing chronic neck pain: a preliminary report of a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial: clinical trial NCT0033272. Pain Physician. 2006;9:333-346.

29. Manchikanti, et al. Evaluation of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks in the management of chronic low back pain: preliminary report of a randomized, double-blind controlled trial: clinical trial NCT00355914. Pain Physician. 2007;10:425-440.

30. Barnsley, et al. Lack of effect of intraarticular corticosteroids for chronic pain in the cervical zygapophyseal joints. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994;330:1047-1050.

31. Kim, et al. Cervical facet joint injections in the neck and shoulder pain. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2005;20:659-662.

32. Fuchs, et al. Intraarticular hyaluronic acid versus glucocorticoid injections for nonradicular pain in the lumbar spine. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2005;16:1493-1498.

33. Schofferman J., Kine G. Effectiveness of repeated radiofrequency neurotomy for lumbar facet pain. Spine. 2004;29:2471-2473.

34. Tekin, et al. A comparison of conventional and pulsed radiofrequency denervation in the treatment of chronic facet joint pain. Clin. J. Pain. 2007;23:524-529.

35. Lord, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;335:1721-1726.

36. Birkenmaier, et al. Percutaneous cryodenervation of lumbar facet joints: a prospective clinical trial. Int. Orthop. 2006.

37. Mogalles, et al. Percutaneous laser denervation of the zygapophyseal joints in the pain facet syndrome. Zh. Vopr. Neirokhir. Im. N N. Burdenko. 2004;1:20-25.

38. Cohen S.P. Sacroiliac joint pain: A comprehensive review of anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Anesth. Analg. 2005;101:1440-1453.

39. Maguars, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of sacroiliac corticosteroid injections in spondylarthropathies: a double-blind study. Br. J. Rheumatol.. 1996;35:767-770.

40. Cohen, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled study evaluating lateral branch radiofrequency denervation for sacroiliac joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:279-288.

41. Derby, et al. The ability of pressure-controlled discography to predict surgical and non-surgical outcomes. Spine. 1999;24:364-371.

42. Oh W.S., Shim J.C. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency denervation of the ramus communicans nerve for chronic discogenic low back pain. Clin. J. Pain. 2004;20:55-60.

43. Bryan, et al. Fluoroscopic assessment of epidural contrast spread after caudal injection. Las Vegas, NV: ISIS, 7th Annual Scientific Meeting; August 1999.

44. Khot, et al. The use of intradiscal steroid therapy for lumbar spinal discogenic pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2004;29:833-836.

45. Manchikanti, et al. Effectiveness of caudal epidural injections in discogram positive and negative chronic low back pain. Pain Physician. 2002;5:18-29.

46. North American Spine Society Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines for Multidisciplinary Spine Care: Diagnosis and Treatment of Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis. 2008.

47. Weinstein J.N., Lurie J.D., Tosteson T.D., et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2007;356(22):2257-2270.

48. Weinstein, et al. Surgical vs nonsurgical therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358(8):794-810.

49. North American Spine Society, Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines for Multidisciplinary Spine Care: Diagnosis and Treatment of Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. 2007.