50 The Role of Spinal Fusion and the Aging Spine

Stenosis without Deformity

KEY POINTS

Introduction

Basic Science

Radiographically, cervical stenosis is often diagnosed using a radiographic measurement called the Pavlov ratio. This ratio is defined as the ratio between the sagittal diameter of the spinal canal and the sagittal diameter of the vertebral body, as measured on a lateral radiograph. A ratio of greater than 1 is considered normal, while a ratio of less than 0.8 is considered to be diagnostic for spinal stenosis. A cervical MRI can help determine the etiology of the compression if the source is a herniated disc or a redundant ligamentum flavum. Additionally, an MRI can show any evidence of spinal cord compression, such as a lack of cerebrospinal fluid around the spinal cord and/or myelomalacia within the cord itself. A CT scan can be used to diagnose bony abnormalities such as osteophytes or hypertrophied facet joints.

Stenosis in the Cervical Spine

Case 1

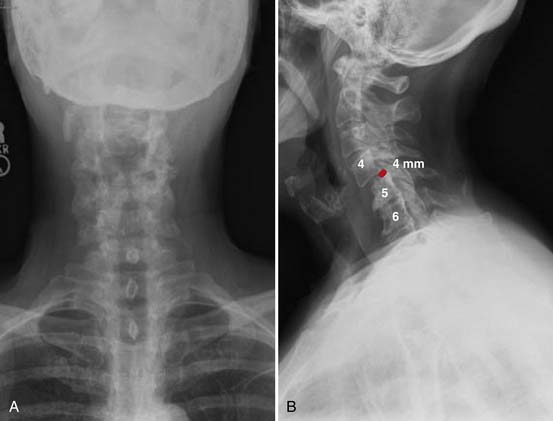

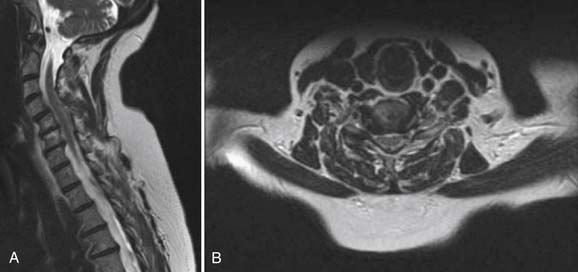

Radiographs, seen in Figure 50-1A and B, demonstrate loss of normal cervical lordosis, severe spondylosis, and a spondylolisthesis of C4 on C5. Sagittal and coronal MRI cuts, seen in Figure 50-2A and B, demonstrate significant spinal stenosis, loss of normal disc height, and severe spinal cord compression with myelomalacia.

The patient was taken to the operating room for a combined anterior and posterior cervical decompression and fusion. Discectomies and interbody fusion were performed with allograft spacers and an anterior plate at C4-5, C5-6, and C6-7. This portion of the procedure restored normal lordosis and addressed the anterior pathology, including reduction of the spondylolisthesis at C4-5. The posterior procedure included laminectomy from C3 to C7 with screw and rod fixation from C3 to C7 as well (Figure 50-3A and B).

Clinical Practice Guidlines

The location of the compressive pathology in cervical stenosis is important, as it dictates the operative approach. Cervical stenosis due to a central or moderate-sized posterolateral cervical herniated nucleus pulposus is best treated with an anterior approach, in order to adequately remove the compressive pathology. This anterior cervical discectomy is typically combined with a fusion. Fusion is achieved with or without instrumentation, consisting of an anterior plate and screws. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) has been described with good results without the use of instrumentation. An anterior cervical discectomy (ACD) without fusion is rarely performed today, and is almost never performed for multilevel disease. Discectomy without fusion has been reported in a prospective, randomized trial to be equivalent to ACDF for the treatment of cervical radiculopathy.1 For the treatment of myelopathy, ACD without fusion has been reported to result in good relief of neck and arm pain as well as a 76% rate of return to work.2 However, ACD without fusion has been shown in other case series to be associated with worsening of preexisting cervical myelopathy in 3.3% of cases.3 Worsening of symptoms after ACD without fusion was also reported by Nandoe Tewarie et al in a retrospective review of 102 patients evaluated up to 18 years after surgery.4 While ACD alone has been shown to be successful in the treatment of cervical myeloradiculopathy, the possibility of worsening of symptoms, combined with the difficulty of revision of anterior cervical surgery, makes this a possible yet unattractive surgical option.

If the compressive pathology is secondary to redundant ligamentum flavum, hypertrophied facet joints, or other posterior pathology, then a posterior approach allows the surgeon to directly decompress the offending agent. A posterior-only approach is only indicated if neutral or lordotic alignment of the cervical spine is maintained. A kyphotic deformity in the cervical spine often mandates an anterior approach to restore the normal cervical sagittal alignment. Decompression from a posterior approach consists of laminotomy, laminectomy, or laminoplasty. Removal of significant portions of the facet joints should be avoided in order to avoid causing iatrogenic postlaminectomy cervical kyphosis. Raynor et al reported a cadaveric study comparing the potential degrees of instability on biomechanical testing of intact specimens, and following 50% facetectomy, and 70% facetectomy. The conclusion of this study was the recommendation that a facetectomy should involve less than 50% of the facet joint in the absence of fusion, in order to avoid spinal instability.5 Postlaminectomy kyphosis after posterior cervical decompression alone is common when there is evidence of hypermobility on preoperative flexion-extension radiographs. A cervical fusion should be considered after posterior decompression if:

A combined anterior and posterior approach may be needed for kyphotic deformities with spinal stenosis and for multiple level disease. Posterior instrumentation and fusion is usually warranted when performing three or more cervical corpectomies or when doing four or more cervical discectomies.

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Stenosis in the Thoracic Spine

Case 2

The patient had a CT scan of her spine that demonstrated pathologic fractures of T5 and T6 and lytic lesions at multiple spinal levels with bony destruction, predominantly from T3 to T6, with encroachment upon the adjacent central canal and neural foramen (Figure 50-4). These findings were most suggestive of metastatic lesions. MRI of her spine demonstrated metastatic disease with multilevel involvement and posterior epidural extension in T5 and T6 resulting in spinal cord compression (Figure 50-5).

The patient underwent a T3 to T6 laminectomy for extradural tumor, posterolateral fusion of T2 to T10, and open biopsy of the presumed metastatic lesion. Pathologic examination was consistent with metaplastic breast cancer (Figure 50-6). The patient tolerated the procedure well without complication. At the time of discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, lower extremity motor strength had improved to 3/5, and sensation had improved as well. Bladder function did not return and a Foley catheter was maintained. The neurogenic bowel responded well to enema, Dulcolax, Colace, and senna.

Treatment for thoracic stenosis is usually limited to decompression alone. The decision on whether to use an anterior, posterior, or transthoracic approach depends on the source of the compressive pathology. Fusion, historically, has rarely been indicated due to the greater inherent stability of the thoracic spine afforded by the rib cage and sternum. Palumbo et al described a retrospective review of 12 patients treated for thoracic stenosis. All were treated with a decompression alone, without fusion. Although the majority of their patients improved with regard to pain, ambulation, and neurological function, five patients exhibited early deterioration of symptoms due to recurrent stenosis, deformity/instability, or both. The authors imply that a decompression at the thoracolumbar junction was more prone to instability.6

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Controversy exists in the literature with regard to whether a spinal fusion should be added to decompression. Decompression alone without fusion has been reported to treat lumbar spinal stenosis with good results. However, other reports in the literature, primarily those including patients with instability, report better clinical outcomes with addition of spinal fusion. Yone et al reported on a group of 34 patients with lumbar spinal stenosis.7 Of this group, 17 patients had radiographic spinal instability as described by Posner. Ten patients underwent decompression and fusion, and the remaining seven underwent decompression alone. The decompression-alone patients had significantly worse Japanese Orthopaedic Association back scores. Still others report no difference in clinical outcomes for patients treated with decompression alone and decompression plus fusion.8,9

Expansive laminoplasty has been reported as an alternative to lumbar decompression and fusion, with good results.10 This procedure shares the technical demands present in cervical laminoplasty.

Stenosis in the Lumbar Spine

Case 3

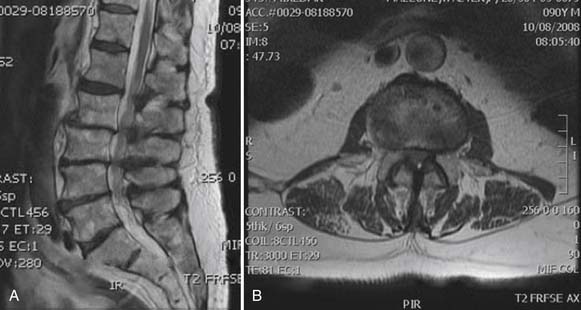

Radiographs, seen in Figures 50-7A and B, demonstrate advanced degenerative changes, with significant disc height loss, large disc osteophyte complexes, and facet hypertrophy from L2 to L5. Sagittal and coronal MR images seen in Figure 50-8A and B show severe central, lateral recess, and foraminal stenosis, with increased fluid in the zygapophyseal joints and buckling of the ligamentum flavum.

The patient was taken to the operating room for a L2 to L5 decompression and posterolateral instrumented fusion. Postoperative images are shown in Figure 50-9A and B. At last follow-up, the patient had returned to his premorbid level of functioning, with complete resolution of his claudication symptoms and no postoperative pain.

1. Hauerberg J., et al. Anterior cervical discectomy with or without fusion with ray titanium cage: a prospective randomized clinical study. Spine. 2008;33(5):58-64.

2. Rao P.J., et al. Clinical and functional outcomes of anterior cervical discectomy without fusion. J. Clin. Neurosci.. 2008;15(12):1354-1359.

3. Bertalanffy H., Eggert H.R. Complications of anterior cervical discectomy without fusion in 450 consecutive patients. Acta Neurochir. (Wien). 1989;99(1-2):41-50.

4. Nandoe Tewarie R.D., Bartels R.H., Peul W.C. Long-term outcome after anterior cervical discectomy without fusion. Eur. Spine J.. 2007;16(9):1411-1416.

5. Raynor R.B., Pugh J., Shapiro I. Cervical facetectomy and its effect on spine strength. J. Neurosurg.. 1985;63(2):278-282.

6. Palumbo M.A., et al. Surgical treatment of thoracic spinal stenosis: a 2- to 9-year follow-up. Spine. 2001;26(5):558-566.

7. Yone K., et al. Indication of fusion for lumbar spinal stenosis in elderly patients and its significance. Spine. 1996;21(2):242-248.

8. Cornefjord M., et al. A long-term (4- to 12-year) follow-up study of surgical treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. Eur. Spine J.. 2000;9(6):563-570.

9. Grob D., Humke T., Dvorak J. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis: decompression with and without arthrodesis. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am.. 1995;77(7):1036-1041.

10. Adachi K., et al. Spinal canal enlargement procedure by restorative laminoplasty for the treatment of lumbar canal stenosis. Spine J.. 2003;3(6):471-478.