51 The Role of Spinal Fusion and the Aging Spine

Stenosis with Deformity

KEY POINTS

Introduction

Adult scoliosis is a common and sometimes disabling degenerative condition of the spine, with an overall prevalence reported in up to 60% of the elderly population.1 Adult scoliosis has a marked impact on patients’ general medical health and well-being; it has been shown that scoliotic patients have a significantly depressed perception of their mental and physical health in comparison with the general U.S. population. Even when individuals are compared with those having additional comorbidities, the adult scoliosis patients rate lower in clinical health assessment. In addition to the subjective considerations of this progressive disease, severe pain and disability occur in this population.2

Definition of Stenotic Degenerative Disease in Deformity

Neural compression associated with adult lumbar scoliosis is commonly manifested as a radicular pain that may be related to physical activity. As the apex of a curve rotates, there is associated hypertrophy and subluxation of the facet joints in the concavity of the curve. Additionally, collapse in the concavity results in narrowing of a neural foramen between adjacent pedicles. As a result, symptoms occur in the anterior portion of the thigh and leg (resulting from compression of the cephalic and middle lumbar nerve roots). Radiating pain in the posterior portion of the lower extremity is more common on the side of the convexity of the lumbar curve; such pain is due to compression of the caudal lumbar nerve roots and the sacral nerve roots, well caudad to the apex, as the spine curves back to meet the pelvis. 2

Clinical Complex of Symptom Presentation

Neurologic pain occurs with activity-related claudication caused by diminished blood flow to the nerves. It is incumbent upon the healthcare provider to rule out common causes of leg pain such as peripheral vascular disease, cardiac disease, arteriosclerotic vascular disease, and/or primary neurologic disease. Compressive radicular pain occurs on the concave collapsing side of a degenerative scoliosis, from direct compression of the nerve at the exiting foramen or subarticular space. Nerve stretch radicular pain occurs on the convex nerve roots that are exiting from the stenotic collapsing scoliotic spine. Therefore, a patient may present with either convex radicular pain or concave nerve root pain, or both.

Adult Scoliosis Classification

Adult Scoliosis is classified by Aebi 3 using an AO system based on a pathoanatomic etiology and on a temporal onset of deformity. His classification defines adult scoliosis as spinal deformity in a skeletally mature patient with a Cobb angle of more than 10 degrees in the coronal plane. Aebi separates adult scoliosis into four types:

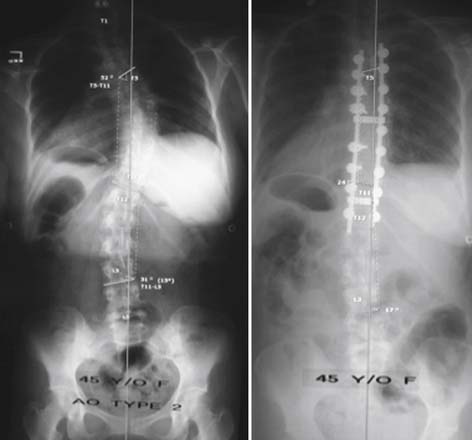

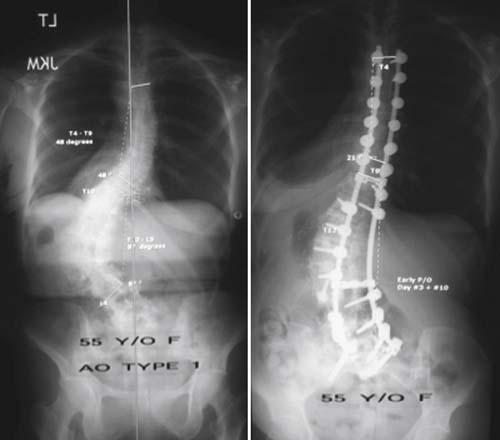

Schwab et al.4 proposed a three-tier classification system for adult scoliosis based on parameters of coronal and sagittal plane. These radiographic criteria include lumbar lordosis, location of coronal curve apex, olisthesis of vertebra segments relative to each other, and sagittal balance on x-ray (Figures 51-3 through 51-6). The classification system has accurately correlated radiographs with clinical significance, in an attempt at suggesting the most appropriate successful treatment in the adult patient. The rate of disease progression is influenced by the magnitude of the curve, the degree of lateral listhesis, the quality of the bone and the severity of associated spondylotic disease. Table 51-1 shows two classification schemes.

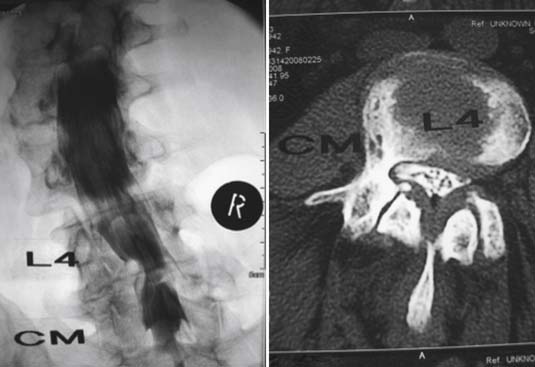

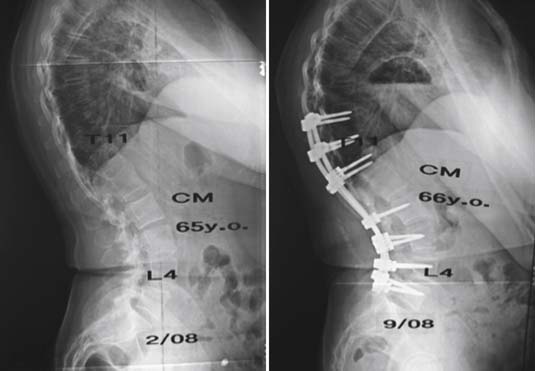

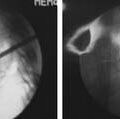

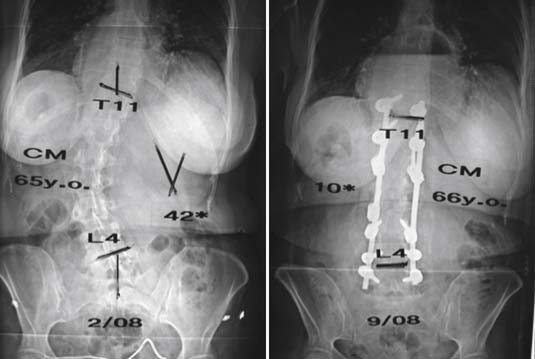

FIGURE 51-3 A 66-year-old female with symptoms of back pain and pseudo-radicular leg pain plus neurogenic claudication. She had an AO (Aebi) type 1 de novo scoliosis curve pattern, also categorized as a Schwab type 5, A+ pattern. After work-up and failure of extended nonoperative treatment, she underwent a posterior multilevel spine decompression /laminectomy and stabilization reconstruction / realignment with fusion and segmental pedicle screw implant instrumentation. Follow-up evaluation demonstrated excellent clinical improvement with resolution of symptoms and an excellent radiographic result, similar to that demonstrated in Figure 51-6.

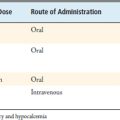

| Aebi – Eur. Spine J, 2005 | Schwab et al. – Spine, 2006 |

|---|---|

Considerations for Nonsurgical or Surgical Management

Surgical management of spinal disorders in the elderly poses challenges not faced in younger patients. Poor bone quality, the possibility of extensive spinal degenerative changes, and changes in sagittal alignment with increased thoracic kyphosis and loss of lumbar lordosis all complicate surgical management. The presence of multiple coexisting medical conditions, reduced wound-healing potential, and malnutrition can markedly increase the risk of complications for extensive surgical procedures. Osteoporosis and osteopenia complicate fixation options. The option of harvesting large quantities of autogenous iliac crest bone graft is not practical in patients with poor bone stock and osteopenia. Additionally, complications of fusion procedures in the elderly may lead to adjacent segment degeneration and the development of junctional kyphosis.

Goals of Treatment (See Table 51-2)

The accepted and basic general goals of surgical management of the spine should include:

Surgical Procedures

The types of surgical procedures include:

Outcomes Associated with Spinal Deformity Treated with Surgical Decompression

Frazier, Lipson, Fossel, and Catz5 published their report in 1997, of a series of 90 patients with preoperative scoliosis associated with back pain, who were treated surgically and followed at 6 months and 24 months after surgery. These authors show that there was an increase in olisthesis, but this fact was associated with greater improvement in walking capacity at 6 months and at 24 months after surgery. Their data indicated that minor increases in the olisthesis after surgery for spinal stenosis generally were well tolerated by the patients. These authors showed that results support that preoperative scoliosis is associated with less favorable outcomes in patients who undergo decompression alone for spinal stenosis.

Operative Treatment of Degenerative Lumbar Scoliosis Associated with Spinal Stenosis

Patients who present with symptoms of spinal stenosis and who have degenerative scoliosis less than 20 degrees and without instability may be treated with spinal decompression only. Male patients with large vertebral structures and stabilizing osteophytes can tolerate more than two-level laminectomy without fusion. Otherwise, patients with degenerative scoliosis more than 15 to 20 degrees, lateral subluxation, or dynamic instability should be treated with decompression and fusion. Simmons6 selects different fusion strategies according to his classification types of degenerative scoliosis; pedicle screws are considered the most appropriate fixation method for the aging osteoporotic bone with absent posterior elements after decompression. It is often imperative to extend the fusion to the sacrum with the addition of multiple fixation points in the sacrum and the pelvis to reduce increased strains to the implants and help healing of the fusion.

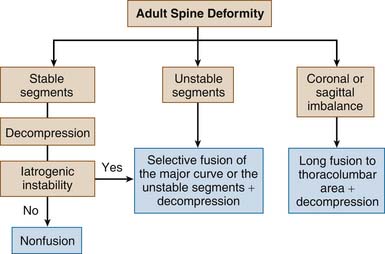

In referencing an article published by Poloumis, Transfeldt, and Denis,7 a modification of their proposed treatment algorithm for patients can be established (shown in Figure 51-7). An extensive study of their patients was made, for which treatment was determined by using their algorithm, which included statistical significant improvement outcomes measured by SF 36, Oswestry, and VAS scores postoperatively.

FIGURE 51-7 Algorithm for adult spine deformity.

(Adapted from Ploumis A, Transfeldt EE, Denis F: degenerative lumbar scoliosis associated with spinal stenosis, Spine J 7(4):428-36, 2007.)

The important consideration for surgery is whether or not the spinal segments are:

If the initial spine is stable, then a decompressive operation is indicated. The decompression alone would be sufficient unless iatrogenic instability is produced at the time of surgery. If iatrogenic instability is produced, then a selective fusion of the major curve should be performed over the area of decompression. If the spine shows instability of the segments prior to commencing surgery, then a selected fusion of the major curve with decompression should be planned and carried out. In contrast, if the preoperative analysis of the patient shows a coronal or sagittal plane imbalance, then a long fusion from the thoracolumbar area, along with decompression of the lumbar area, is planned and carried out (see Figure 51-7).

Principles for Selecting Fusion Levels in Adult Spinal Deformity with Lumbar Curves

An article by Kuklo8 suggested some key points for consideration of surgical levels. Kuklo stated that sagittal imbalance is poorly tolerated in the adult scoliosis patient (Figure 51-8). Surgery should leave the patient with a good sagittal alignment; preoperative workup should include evaluation of adjacent segment disease with discographic evaluation of the degenerated discs as well as pain provocative injection tests of the facet joints in determining fusion levels.

Spinal Stenosis with Scoliosis

In 1992, Simmons and Simmons6 published in Spine their retrospective review of a series of 40 patients who had lumbar scoliosis associated with spinal stenosis and symptoms of neurogenic claudication and were treated with posterior decompression and pedicle screw fixation techniques. In follow-up at an average of 44 months, 38 patients (93%) reported mild or no pain. These workers reported no deaths and no instrumentation-related failures or pseudoarthrosis in their series.

With regard to correction and stabilization with fusion, they recommended that pedicle screw instrumentation systems offered the most advantageous method of handling the difficult problems after removal of posterior elements. Simmons and Simmons believed that long fusions incorporating the entire scoliotic curve were necessary in most patients, because a fusion from the lower portion of the thoracic spine down to the sacrum would often be required. They felt that it was important to end the fusion at a disc space that appeared level. (Table 51-3 shows the operative treatment guidelines and principles described by Simmons and Kuklo.)

| Indications for Surgery |

Rate of Complications in Scoliosis Surgery

Weiss and Goodall9 published a report in Scoliosis in August 2008 that stated that a meta-analysis review of scoliosis surgery checking for complications revealed 2590 titled articles. Although the rates varied, scoliosis surgery had a very high rate of complications, averaging 44% for adults (range 10% to 78%) as published in 11 different studies. (Table 51-4 summarizes surgical complications in treatment of adult scoliosis.)

| Adult Scoliosis∗∗: 11 published studies |

Guigui and Blamoutier10 published a treatise in French in 2005 in the review of orthopedic surgery. Their review of 3311 patients during a 12-month period who underwent surgical treatment of spine deformity found that 704 patients (21.3%) had one or more complications (850 complications) during or shortly after the index operation. The categories of complications were listed as:

Older patients have an overall higher rate of complications. Ocular blindness is a serious complication that requires special note. A review by Myers and Stevens implies a relationship of blindness to operative time, blood loss, and operative hypotension, as well as an association with direct compression of the eye.

1. Kanter A.S., Asthagiri A.R., Shaffrey C.I. Aging spine: challenges & emerging techniques: chap. 3. Clin. Neur. 2007;54:10-18.

2. Spivak J.M. Current concepts review: degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am.. 1998;80:1053-1066.

3. Aebi M. The adult scoliosis. Eur. Spine J.. 2005;14:925-948.

4. Schwab F., Farcy J.P., Bridwell K., Berven S., Glassman S., Harrast J., Horton W. A clinical impact classification of scoliosis in the adult [deformity]. Spine. 2006;31(18):2109-2114.

5. Frazier D.D., Lipson S.J., Fossel A.H., Katz J.N. Associations between spinal deformity and outcomes after decompression for spinal stenosis. Spine. 1997;22(17):2025-2029.

6. Simmons E.D: Surgical treatment of patients with lumbar spinal stenosis with associated scoliosis, Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res., 348:2001, 45-53.

7. Ploumis A., Transfeldt E.E., Denis F. Degenerative lumbar scoliosis associated with spinal stenosis. Spine J.. 2007;7(4):428-436.

8. Kuklo T.R. Principles for selecting fusion levels in adult spinal deformity with particular attention to lumbar curves and double major curves. Spine. 2006;31(19 Suppl):S132-S138.

9. Weiss R.R., Goodall D. Rate of Complications in Scoliosis Surgery-A Systematic Review of the Pub Med Literature. Scoliosis. 2008;3(9):1-18.

10. Guigui P., Blamoutier A. Complications of Surgical Treatment of Spinal Deformities: A Prospective Multicentric Study of 3311 Patients. Rev. Chir. Orthop. Reparatrice. Appar. Mot. (Groupe d’Etude de la Scoliose). 2005;91(4):314-327.