6 The Role of Nutrition, Weight, and Exercise on the Aging Spine

Nutrition

Elderly populations are predisposed to malnutrition due to a variety of causes. The physiological changes associated with aging are altered glucose regulation and impaired hormonal homeostasis. There is decreased absorption of macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and fatty acids) as well as micronutrients.1 The decreased absorption of micronutrients in the elderly population is significant for cobalamin, calcium, vitamin D, riboflavin, and niacin.

Calcium absorption declines in both sexes in the elderly, and is directly related to vitamin D metabolism. Cobalamin (vitamin B12) absorption decreases in the elderly and predisposes them to subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord.2 Other vitamin B complexes may also have malabsorption, leading to neuropathies. The elderly have consistently lower levels of vitamin D. In a European study, vitamin D levels are lowest in winter in the elderly.3 This tendency of decreased sun exposure and decreased capacity of the aging kidney to convert vitamin D to active form may reduce endogenous levels of vitamin D. Western diets only supply 25% to 50% of the vitamin D daily requirement; hence, supplementation in the elderly is crucial.

Anorexia and decreased food intake is prevalent in the elderly population.4 Other than the previously noted causes of anorexia, elderly patients also suffer from psychological anorexia. It may originate from various life events such as loneliness, death of a spouse, lack of social life, estrangement from family, and loss of independence. It is important to recognize these major life events and provide the elderly population with counseling and support. Anorexia may also originate from the natural process of aging and changes within the central nervous centers for feeding and hydration. Although this change is inevitable and irreversible, it should not necessarily lead to undernourishment but merely readjust the food intake to the new levels. However, due to the complex interactions of aging, coexisting conditions, and life events occurring around aging, it may lead to malnutrition if not monitored.

Obesity

Obesity in the elderly population is a growing problem. Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 kg/m2. A BMI between 25 to 29 kg/m2 is classified as overweight. The prevalence of obesity in the general population in the United States for the year 2007 is between 25% and 29% in most states, as published by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in their annual report. A multicenter study in Europe called Survey in Europe on Nutrition and the Elderly: a Concerted Action (SENECA) published a report noting that 20% of the elderly population was obese.1

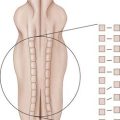

Traditionally, obesity is measured as an index of height and body weight. During aging, the elderly undergo height reduction due to muscle atrophy and bone resorption. On an average, an elderly patient undergoes a 1.5 to 2 cm height reduction over a span of 10 years. Thus, BMI may not be an accurate index of obesity in the elderly. Intra-abdominal fat content assessed by abdominal girth measurement may be a better index. However, there is no established standard protocol for it yet.

Obesity increases the stress on the aging vertebral column by increasing the load-bearing capacity. This excessive load-bearing of the vertebral column predisposes the spinal cord to disc degeneration, facet joint syndrome, and hyperostosis.5 Obesity also predisposes the elderly to nerve entrapment syndromes in the spine and in the limbs such as carpal tunnel syndrome.6 Radicular back pain has a higher incidence in the elderly with obesity compared to healthy elderly people.7 Also, back pain is more severe in obese patients compared to healthy elderly patients. The SF-36 (Short Form) physical component summary score and disease-specific measure and the Oswestry Disability Index are 1.5 times worse in obese elderly patients with spinal diseases as compared to controls.7 Obesity also decreases the functional status of elderly patients and predisposes them to multisystem pathologies.

Exercise

Exercise prevents osteoporosis in the vertebral column and increases bone mass. The principle of exercise in osteoporosis is based on Wolff’s law.8 Wolff’s law states that bone density and strength are a function of the direction and magnitude of mechanical stresses acting on that bone.9 Weight-bearing exercises are performed in osteoporosis patients.10 These include exercise like step training, where the patient spends 10 minutes of stepping up and down from a platform of about 6 to 8 inches in height. It is important to advise elderly patients to take adequate rest to prevent hypoxia. Also, elderly patients should be recommended to use good shock-bearing shoes and perform the exercise in a safe environment. The weight-bearing exercise facilitates osteoblastic activity and promotes increased bone mass.

Aerobic exercises and swimming may contribute to healthy living by conditioning other organ systems but have no effect on the aging spine.11

1. van Staveren W.A., de Groot L.C., Burema J., et al. Energy balance and health in SENECA participants. Survey in Europe on Nutrition and the Elderly, a Concerted Action. Proc. Nutr. Soc.. 1995;54:617-629.

2. Hunter G.M., Irvine R.E., Bagnall M.K. Medical and social problems of two elderly women. BMJ. 1972;4:224-225.

3. van der Wielen R.P., Lowik M.R., van den Berg H., et al. Serum vitamin D concentrations among elderly people in Europe. Lancet. 1995;346:207-210.

4. Chapman I.M., MacIntosh C.G., Morley J.E., et al. The anorexia of ageing. Biogerontology. 2002;3:67-71.

5. Julkunen H., Heinonen O.P., Pyorala K. Hyperostosis of the spine in an adult population: its relation to hyperglycaemia and obesity. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1971;30:605-612.

6. Lam N., Thurston A. Association of obesity, gender, age and occupation with carpal tunnel syndrome. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 1998;68:190-193.

7. Fanuele J.C., Abdu W.A., Hanscom B., et al. Association between obesity and functional status in patients with spine disease. Spine. 2002;27:306-312.

8. Burger E.H., Klein-Nulen J. Responses of bone cells to biomechanical forces in vitro. Adv. Dent. Res. 1999;13:93-98.

9. Frost H.M. From Wolff’s law to the Utah paradigm: insights about bone physiology and its clinical applications. Anat. Rec. 2001;262:398-419.

10. Elward K., Larson E.B. Benefits of exercise for older adults. A review of existing evidence and current recommendations for the general population. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 1992;8:35-50.

11. Gauchard G.C., Gangloff P., Jeandel C., et al. Physical activity improves gaze and posture control in the elderly. Neurosci. Res. 2003;45:409-417.