Chapter 20 The Retrodrill Technique for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Introduction

Arthroscopic controlled retrograde drilling of femoral and tibial sockets and tunnels using a specially designed cannulated drill pin and retrocutter (Fig. 20-1) provides greater flexibility for anatomical graft placement and avoids previous tunnels and intraosseous hardware in revision cases. Inside-out drilling of femoral and tibial sockets minimizes incisions and eliminates intraarticular cortical bone fragmentation of tunnel rims common to conventional antegrade methods. This technique is also ideal for skeletally immature patients because drilling and graft fixation through growth plates may be avoided. Initial tunnel positioning (and not referencing) for cannulated drill guide pin placement is carried out from outside-in. This technique (outside-in/inside-out) combines the advantages of the two-incision and one-incision techniques. In fact, it permits surgeons, as with the two-incision technique, to drill a pin guide from outside to inside in order to obtain the correct anatomical insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) (Fig. 20-2), which is otherwise not reproducible from inside-out.

This technique permits the surgeon to prepare a femoral and a tibial socket or tunnel by initiating the socket drilling from the intraarticular surfaces in an inside-out method (Fig. 20-3). Since November 2004, our preferred technique for hamstring (autogenous quadrupled semitendinosus/gracilis) ACL reconstruction incorporates the just-mentioned femoral socket creation. In recent years, arthroscopically assisted ACL reconstruction has become the procedure of choice. Initially, arthroscopic techniques required two incisions for outside-in drilling of bone tunnels, but there has been a trend toward using a single incision with inside-out drilling of the femoral tunnel. Those who advocate the two-incision technique state that they do so primarily because they believe that the two-incision procedure facilitates accurate femoral tunnel placement.1,2 Harner et al3 found no difference in tunnel placement using the two-incision technique, whereas Schiavone et al4 found that the femoral tunnels were significantly more vertical in the one-incision procedure. We have performed two-incision ACL reconstruction routinely since 1977 with very favorable results. The recent variation in our technique affords a reduction in morbidity associated with improved cosmesis and quicker postoperative recovery. A factor related to our success appears to be the result of a more anatomically positioned femoral tunnel, which in our hands is difficult to accomplish with single-incision transtibial femoral socket creation. Arnold et al,1 who examined the arthroscopic appearance of the ACL attachment in fresh frozen cadaver knees, found that the ligament consistently inserted on the lateral wall of the notch. No fibers were found to attach high in the roof. Furthermore, they found that the single-incision technique always missed the anatomical femoral ACL insertion. Another advantage of the retrodrill is that the traditional (outside-in) drilling methods disrupt the proximal tibial cortex with the drill penetration and may lead to tunnel widening. Retrodrilling produces a consistently smooth tibial and femoral intraarticular socket or tunnel entrance, maintaining the desired cortical integrity (Fig. 20-4).

Femoral Tunnel Placement

Over the past several decades, bioengineers and orthopaedic surgeons have applied the principles of biomechanics to gain valuable information about the tunnel placement in ACL reconstruction and its relationship to knee stability. Still, both short- and long-term clinical outcomes studies have revealed that 11% to 32% of the patients experience unsatisfactory results after ACL reconstruction.5 The position of an ACL graft is the most critical surgical variable because it has a direct effect on knee biomechanics and, ultimately, on clinical outcome. Currently, limited data are available from prospective studies that identify the optimal intraarticular position of an ACL graft on the femur and tibia. A recent review of the literature by Beynnon et al6 shows that the center of the femoral attachment of an ACL graft should be located along a line parallel to the Blumensaat line, just posterior to the center of the normal ACL’s insertion to bone at either the 10-o’clock position (right knee) or the 2-o’clock position (left knee) when observed through the femoral notch. Graft placement, especially the tunnel on the femoral side, has long been a subject of debate. To date, most surgeons choose to place it in the footprint of the anteromedial bundle of the ACL (i.e., near the 11-o’clock position on the frontal view of the right knee). However, results of biomechanical and clinical research have suggested that it is necessary to place the tunnel more laterally for rotatory knee stability. Yamamoto et al5 compared a lateral and an anatomical tunnel placement using a robotic universal force sensor and concluded that a lateral tunnel placement can restore rotatory and anterior knee stability similarly to an anatomical reconstruction when the knee is near extension. Loh et al7 published a paper studying how well an ACL graft fixed at the 10- and 11-o’clock positions could restore knee function in response to both externally applied anterior tibial and combined rotatory loads by comparing the biomechanical results with each other and with the intact knee. They concluded that the 10-o’clock position more effectively resists rotatory loads when compared with the 11-o’clock position, as evidenced by smaller anterior tibial translation and higher in situ force in the graft. More recently Scopp et al8 performed a biomechanical study on 10 matched pairs of fresh frozen cadaver knees alternately assigned to a standard or an oblique tunnel position (at 10-o’clock) reconstruction. The investigators concluded that an ACL reconstruction using oblique femoral tunnels restored normal knee kinematics. In conclusion, it appears that actually there is a trend toward placing the femoral tunnel more laterally between the anteromedial and posterolateral anterior cruciate footprints (i.e., the 10-o’clock position). Biomechanics helped to clarify that although fixation at 11 o’clock is effective to resist an anterior tibial load, the more lateral 10-o’clock position could achieve better knee stability under rotatory loads (i.e., pivot shift). More recently, Arnold et al9 found that it is possible to replicate the characteristics of the tension curve of the normal ACL with a graft in a tunnel located at the 9-o’clock position.

Surgical Technique

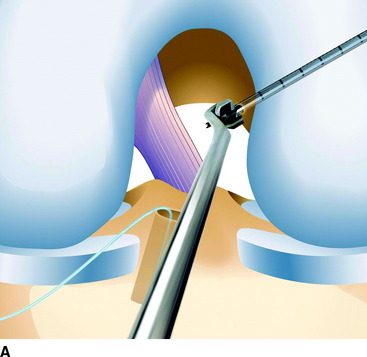

To locate the desired center of the femoral tunnel, we use a femoral guide recently made by Arthrex (Naples, FL) that keys off the over-the-top position. The guide enters the knee from the anteromedial portal and with its curved hook is fastened to the lateral femoral condyle in the over-the-top position at the 10:30 position for the right knee and the 1:30 position for the left knee. Our guide, with its variable hook, permits us to drill a specially designed cannulated guide pin from outside to inside that emerges in the lateral wall of the notch just 4 to 6 mm anterior to the posterior margin of the notch. When drilled, this creates a tunnel 7 to 10 mm in diameter, which leaves a 0.5- to 1-mm rim of posterior cortex. Reproducing this tunnel with the exact location in the frontal, sagittal, and coronal planes with a guidewire drilled from inside-out is quite impossible, especially if done through a predrilled tibial tunnel. With the guide positioned in the notch, a mini (2-cm) lateral skin and fascia incision is carried out corresponding with the tip of the guide, and the drill sleeve is advanced to the femoral cortex along the lateral aspect of the knee (Fig. 20-5). A cannulated threaded pin (3 mm in diameter) is drilled through the drill sleeve and the femoral condyle until it enters intraarticularly, as observed with the arthroscope (see Fig. 20-2). The correct location is confirmed. Then a mini retrograde cutting drill (retrocutter) (Arthrex) 7 to 10 mm in diameter (depending on the width of the graft that has been previously harvested and measured) is introduced in the knee from the anteromedial portal already preloaded on a reverse-threaded instrument. As threads of the guide pin engage the retrocutter, the reverse threads of the drill holder facilitate simultaneous disengagement of the retrocutter from the instrument (Fig. 20-6, A). A handle is set up on the outer end of the pin to permit the manual advancement of the inner end of the pin onto the retrocutter.

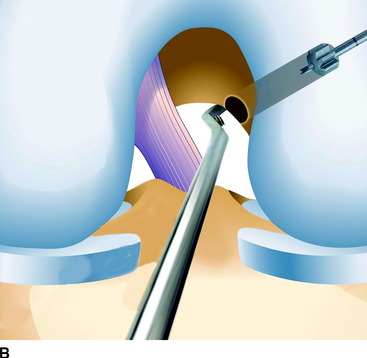

The cannulated pin is also calibrated in order to easily know the lateral condyle width. Then a socket of 2.5 to 3.5 cm is retrodrilled, pulling the drill from outside (Fig. 20-6, B), leaving 1 cm of intact bone. The retrodrill is then gently pushed back in the joint. Once the retrocutter engages its holder, the drill is reversed; reverse drilling securely engages the retrocutter on the holder and simultaneously disengages the retrocutter from the threaded guide pin. A shaver is used to remove any debris in the joint and to chamfer the tunnels edges, and a suture (#2 FiberStik, Arthrex) is introduced in the joint through the cannulated pin for graft passing.

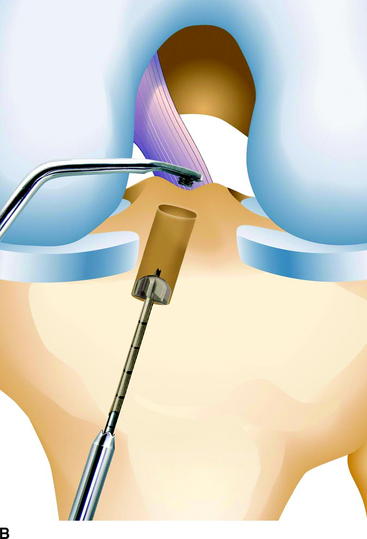

A tibial tunnel of the same diameter is prepared in a routine manner, or a tibial socket can be made in the same way as the femoral (Fig. 20-7) if so planned by the surgeon. The suture is pulled out from the tibial tunnel. The graft (quadruple gracilis and semitendinosus) is marked to locate the exact portion that has to fill the femoral tunnel and is prepared with two #5 Fiberwire (Arthrex) sutures at the femoral end and passed in the knee from the tibial to the femoral tunnel. The fixation sutures exiting the lateral cortex of the femur are passed through a four-hole metal button and tied securely to fix the graft on the femur (Fig. 20-8). Either square or sliding knots can be used for this kind of suspension fixation.

1 Arnold MP, Kooloos J, van Kampen A. Single incision technique misses the anatomical femoral anterior cruciate ligament insertion: a cadaver study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9:194-199.

2 Khon D, Busche T, Carls J. Drill hole position in endoscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthroscop. 1998;6:S13-S15.

3 Harner C, Marks P, Fu F, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: endoscopic versus two incision technique. Arthroscopy. 1994;10:502-512.

4 Panni AS, Milano G, Tartarone M, et al. Clinical and radiographic results of ACL reconstruction: a 5- to 7-year follow-up study of outside-in versus inside-out reconstruction technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;22:77-85.

5 Yamamoto Y, Hsu WH, Woo SL-Y, et al. Knee stability and graft function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a comparison of a lateral and an anatomical femoral tunnel placement. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1825-1832.

6 Beynnon BD, Johnson RJ, Abate J, et al. Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries, part II. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1751-1767.

7 Loh JC, Fukuda Y, Tsuda E, et al. Knee stability and graft function following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: comparison between 11 o’clock and 10 o’clock femoral tunnel placement. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:297-304.

8 Scopp JM, Jasper LE, Belkoff SM, et al. The effect of oblique femoral tunnel placement on rotational constraint of the knee reconstructed using patellar tendon autografts. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:294-299.

9 Arnold MP, Verdonschot N, Van Kampen A. ACL graft can replicate the normal ligament’s tension curve. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13:625-631.

Andersen H, Dyhre-Poulsen P. The anterior cruciate ligament does play a role in controlling axial rotation in the knee. Knee Sur Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1997;5:145-149.

Beynnon BD, Johnson RJ, Abate JA, et al. Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries, part I. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1579-1602.

Markolf KL, Hame S, Hunter DM, et al. Effects of femoral tunnel placement on knee laxity and forces in an anterior cruciate ligament graft. J Orthop Res. 2000;20:1016-1024.

Puddu G, Cerullo G. My technique in femoral tunnel preparation: the retrodrill technique. Tech Orthop. 2005;20:224-227.

Ristanis S, Stergiou N, Patras K, et al. Excessive tibial rotation during high-demand activities is not restored by anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2005;1:1323-1329.

Sommer C, Friederich NF, Muller W. Improperly placed anterior cruciate ligament grafts: correlation between radiological parameters and clinical results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:207-213.