Chapter 16 The respiratory system

Bronchodilators and decongestants

Systemic drugs

Ephedra, Ephedra spp. (Ephedrae Herba)

Constituents

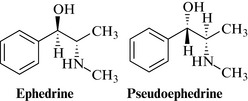

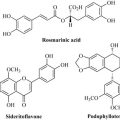

Alkaloids, up to about 3%, but widely varying; the major alkaloid is (–)-ephedrine (Fig. 16.1), together with many others. These include (+)-pseudoephedrine, norephedrine, norpseudoephedrine, ephedroxane, N-methylephedrine, maokonine, transtorine and the ephedradines A–D. Other components are catechin derivatives, and diterpenes, including ephedrannin A and mahuannin A, have been isolated from other species of Ephedra.

Toxicological risks

The herb has been abused as a slimming aid, and an ergogenic aid in sports and athletics, but this is dangerous (Fleming 2008). For example, hypertension and other cardiovascular events, and a case of exacerbation of hepatitis, have been noted with high doses. The absorption of ephedrine and pseudoephedrine is slower after ingestion of the herb than for isolated alkaloid preparations, and the other constituents, the ephedradins, mahuannins and maokonine, are mildly hypotensive; but both the herb and the isolated alkaloids should be avoided by hypertensive patients as well as in cases of thyrotoxicosis, narrow-angle glaucoma and urinary retention. Therapeutic doses of the herb are calculated to deliver up to 30 mg of the alkaloids, calculated as ephedrine.

Theophylline

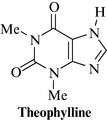

Although a natural xanthine, theophylline (Fig. 16.2), which is found in cocoa (Theobroma cacao), coffee (Coffea spp.) and tea (Camellia sinensis), is almost invariably used as the isolated compound. It is indicated in reversible airways obstruction, particularly in acute asthma. Because of the narrow margin between the therapeutic and the toxic dose, and the fact that the half-life is highly variable between patients, especially smokers and in heart failure or with concurrent administration of other drugs, care must be taken. The usual dose is 125–250 mg in adults, three times daily, and half of that in children.

Inhalations

Camphor

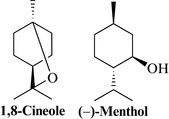

Camphor (Fig. 16.3), a pure natural product, is derived from the Asian camphor tree (Cinnamomum camphora T. Nees & Eberm., Lauraceae). It is often combined with the essential oil containing drugs as an aromatic stimulant and decongestant.

Eucalyptus oil, Eucalyptus spp. (Eucalypti aetheroleum)

Constituents

The oil contains 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol; see Fig. 16.4) as the major component, with terpineol, α-pinene, p-cymene and small amounts of ledol, aromadendrene and viridoflorol, aldehydes, ketones and alcohols.

Menthol

Menthol is a monoterpene (Fig. 16.4) extracted from mint oils, Mentha spp. (especially M. arvensis) or it can be made synthetically. Whole peppermint oil is used in herbal combinations to treat colds and influenza (as well as for colic, etc.; see Chapter 14), but isolated menthol is an effective decongestant used in nasal sprays and inhalers. Menthol can be irritant and toxic in overdose, but is generally well tolerated in normal usage.

Anti-allergics

Butterbur, Petasites hybridus L.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Butterbur is traditionally used as a remedy for asthma, colds, headaches and urinary tract disorders. It is used as an antihistamine for seasonal allergic rhinitis, and a recent randomized, double-blind comparative study using 125 patients over 2 weeks of treatment showed that butterbur extract is as potent as cetirizine. The anti-inflammatory activity is due mainly to the petasin content. Extracts inhibit leukotriene synthesis and are spasmolytic, and reduce allergic airway inflammation and AHR by inhibiting the production of the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-5, and RANTES (Brattström et al 2010), thus supporting its use in asthma. Use as prophylactic treatment for migraine has also been suggested but further evidence of efficacy is needed (Agosti et al 2006). The usual dose is an extract equivalent to 5–7 g of herb or root. Internal use is not recommended unless the alkaloids are present in negligible amounts or have been removed from preparations, as is the case with the commercially available product, which is a ‘special extract’. Maximum intake of the alkaloids should be less than 1 μg daily for fewer than 6 weeks per year.

Expectorants and mucolytics

Thyme and wild thyme, Thymus vulgaris L. and Thymus serpyllum L. (Thymi herba and Serpylli herba)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Thyme, and oil of thyme, are carminative, antiseptic, antitussive, expectorant and spasmolytic, and, as such, are used for coughs, bronchitis, sinusitis, whooping cough and similar respiratory complaints. Most of the activity is thought to be due to the thymol, which is expectorant and highly antiseptic. Thymol and carvacrol are spasmolytic and the flavonoid fraction has a potent effect on the smooth muscle of guinea pig trachea and ileum. Thymol (Fig. 24.1) is a popular ingredient of mouthwashes and dentifrices because of its antiseptic and deodorant properties. The oil may be taken internally in small doses of up to 0.3 ml, unless for use in a mouthwash, which is not intended to be swallowed in significant amounts.

Thymol is irritant, and toxic in overdose, and should be used with care.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

An infusion of sage is used as a gargle or mouthwash for pharyngitis, tonsillitis, sore gums, mouth ulcers and other similar disorders. Sage extracts and oil have been reported to be antimicrobial. The flavonoids and phenolic acid derivatives have antiviral and anti-inflammatory activity. Sage has a reputation for enhancing memory, and there is some clinical trial evidence (Scholey et al 2008), and the fact that it has anticholinesterase activity, to support this use.

Senega, Polygala senega L. (Polygalae radix)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Senega is used primarily for chronic bronchitis, catarrh, asthma and croup. The saponins are the active constituents, as with other mucolytic plant drugs, and senega is usually taken orally as an infusion. The saponins also have immunopotentiating activity to protein and viral antigens, and exhibit less toxicity than quillaia saponins. They are anti-inflammatory and antiseptic. Senega extracts, the senegasaponins and the senegins are hypoglycaemic in rodents, the senegasaponins are inhibitors of alcohol absorption, and the senegins also have anticancer and anti-angiogenic effects in vitro (Arai et al 2011). The dose is usually equivalent to 0.5–1 g of the powdered root.

Ivy, Hedera helix L. (Hederae folium)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Ivy extracts are used in preparations for bronchitis and catarrh, as an expectorant. The saponins and sapogenins are the main active ingredients; they are expectorant and antifungal. Few clinical studies have been carried out, and further work is needed (Holzinger and Chenot 2011). One study showed that after 7 days of therapy with dried ivy leaf extract, 95% of patients showed improvement or healing of their symptoms, and it was safe and well-tolerated: the overall incidence of adverse events was 2.1%, mainly gastrointestinal disorders (Fazio et al 2009).

Both the saponin and the flavonoid fractions have spasmolytic effects.

Tolu balsam, Myroxylon balsamum L. (Balsamum tolutanum)

Ipecacuanha, Cephaelis ipecacuanha A. Rich and C. acuminata Karsten (Ipecacuanhae radix)

Constituents

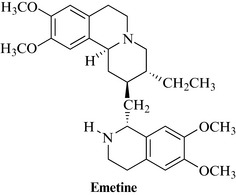

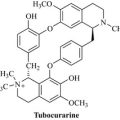

Both species contain isoquinoline alkaloids as the active principles, usually about 2–3%. The most important are emetine (Fig. 16.6) and cephaeline, with psychotrine and some others.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Ipecac extract is an ingredient of many cough preparations, both elixirs and pastilles, because of its expectorant activity. It is also well known as an emetic and has been employed to induce vomiting in cases of drug overdose, particularly in children. This use is, however, highly controversial (Quang and Woolf 2000). The alkaloids are amoebicidal, but the emetic activity means that they are rarely used for this purpose. There is little clinical evidence for the use of ipecac as an expectorant but it has a long history of traditional use. Ipecacuanha Liquid Extract BP is given at a dose of 0.25–1 ml.

Ipecac causes vomiting in large doses and the alkaloids are cytotoxic.

Cough suppressants

Codeine

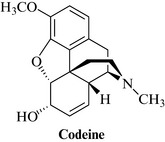

Although found in opium (Papaver somniferum), codeine (Fig. 16.7) is usually used as the isolated alkaloid, in the form of a salt (usually phosphate) formulated as a linctus, at a dose of 5–10 mg 4-hourly, to treat cough. The dose for treating diarrhoea and pain is much higher (up to 240 mg daily in divided doses).

Demulcents and emollients

Coltsfoot, Tussilago farfara L. (Tussilago folium)

Elderflower and Elderberry (fruit), Sambucus nigra L. (Sambuci flos, Sambuci fructus)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Elder flowers are used as an infusion or herbal tea, and a mixture with peppermint is a traditional remedy for colds and influenza. They induce perspiration, which is thought to be beneficial in such cases. Recent studies show an in vitro activity against several strains of influenza virus, and a clinical study has also demonstrated a reduction in the duration of flu symptoms for the berries (see Vlachojannis et al 2010 for review). The effect was attributed to an increase in inflammatory cytokine production as well as a direct antiviral action. The usual dose is about 3 g of flowers infused with 150 ml of hot water, but is not critical. Elder flowers are non-toxic and no side effects have been reported. Both the berries and the flowers are used to make cordials which are taken medicinally for their reputed antioxidant and antiviral properties.

Mallow flower and leaves, Malva sylvestris L. (Malvae flos and Malvae folium)

Marshmallow leaf and root, Althea officinalis L. (Althaeae folium, Althaeae radix)

Pelargonium, Pelargonium sidoides DC and P. reniforme CURT (Pelargonii radix)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

In Germany, a standardized extract of Pelargonium sidoides (EPs® 7630, also known as Umckaloabo®) is registered by the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) for the indication ‘acute bronchitis’ and several randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials support its efficacy in adults and children (Agbabiaka et al 2008). The extract EPs® 7630 has multiple effects which are beneficial in respiratory infections, and include antiviral, antibacterial, immunomodulatory and cytoprotective effects. It also increases the frequency of ciliary beats, thus helping to remove pathogens for the upper respiratory tract, and inhibits the interaction between bacteria and host cells. A recent study has found that EPs® 7630 interferes with the replication of different respiratory viruses including seasonal influenza A virus strains, RSV, human coronavirus, parainfluenza virus and coxsackie virus (Michaelis et al 2011). This extract is also given to athletes to help strengthen the immune system, which can be compromised by extreme exercise, to protect against colds. A study in athletes submitted to intense physical activity found that Pelargonium sidioides increased the production of secretory immunoglobulin A in saliva, and decreased levels of both interleukin-15 and interleukin-6 in serum, suggesting a strong modulating influence on the immune response associated with the upper airway mucosa (Luna et al 2011).

Immunostimulants

Echinacea, Echinacea pallida (Nutt.) Britt., E. purpurea Moench and E. angustifolia (DC.) Hell. (Echinaceae herba, radix)

Constituents

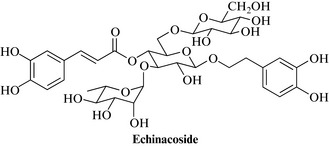

Numerous compounds have been identified, but the most pharmacologically relevant ones are not known. All species contain similar types of compounds, although not necessarily the same individual ones. The most important are the caffeic acid derivatives, including echinacoside (Fig. 16.8) (E. pallida root), cichoric acid (E. purpurea aerial parts) and others, and the alkylamides (found throughout the plant in all three species), which are a complex mixture of unsaturated fatty acid derivatives. Some have a diene or diyne structure (with two unsaturated and two triple unsaturated groups) or a tetraene structure (with four unsaturated groups) linked via an esteramide to a (2)-methylpropane or (2)-methylbutane residue.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Echinacea preparations are available both as traditional herbal medicinal products used to relieve the symptoms of the common cold and influenza type infections, but also as preparations with a well-established use. There is some evidence in the treatment and prevention of respiratory infections, but more limited evidence for slow healing wounds using topical applications. Clinical evidence for uses as an immunostimulant is available for some of the chemically characterised extracts. Overall a series of meta-analyses showed that Echinacea preparations seem to be efficacious both therapeutically (reducing symptoms and duration) and in terms of prophylaxis against the common cold (Shah et al 2007, Woelkart et al 2008). However, Echinacea preparations tested in clinical trials differ greatly. There is better evidence that preparations based on the aerial parts of E. purpurea might be effective for the early treatment of colds in adults but the results are not fully consistent. A mechanism of action has been postulated by Chicca et al (2009), suggesting that the alkylamides dodeca-2 E,4E,8Z,10Z-tetraenoic acid isobutylamide (A1) and dodeca-2E, 4E-dienoic acid isobutylamide (A2) bind to the cannabinoid-2- (CB2) receptor and are the main anti-inflammatory and immune-modulatory principles, acting in synergy. In addition, alkylamides potently inhibit LPS-induced inflammation in human whole blood and exert modulatory effects on cytokine expression, but these effects are not exclusively related to CB2 binding.

Echinacea appears to be safe, although allergic reactions have been reported. The risk of interactions seems to be very limited (Modarai et al 2007).

Astragalus, Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bge. (Astragali radix)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

A number of clinical studies, supported by data from over 1000 patients in China, confirm the use of astragalus as an immunostimulant for use in colds and upper respiratory infections. It is also used prophylactically. In China it is also used as an adjunctive in the treatment of cancer, and appears to potentiate the effects of interferon. It also has antioxidant, hepatoprotective and antiviral activity and is used to enhance cardiovascular function (www.thorne.com 2003). Many animal studies have been carried out, but specific data on toxicity are sparse. In general, astragalus is well tolerated but should probably be avoided in autoimmune diseases.

Andrographis, Andrographis paniculata (Burm.f.) Wall. ex Nees (Andrographis paniculatae herba)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Andrographis is most commonly used as an immune stimulant, but is also reputed to possess antihepatotoxic, antimicrobial, antithrombogenic, antiinflammatory and anticancer properties (www.thorne.com 2003). Andrographolide has been shown to have immunostimulatory activity, shown by an increase in proliferation of lymphocytes and production of interleukin-2, and the antiinflammatory activity has been demonstrated by an inhibition of NFĸB, nitric oxide, PGE2, IL-1β, IL-6, LTB4, TXB2 and histamine (Bao et al 2009, Chandrasekaran et al 2010). In one Chilean study, andrographis herb had a significant drying effect on the nasal secretions of cold sufferers who took 1,200 mg of the extract daily for 5 days (Cáceres et al 1999). A systematic review of the literature has suggested the herb alone (or in combination with Eleutherococcus) may be an appropriate treatment for uncomplicated acute upper respiratory tract infection (Poolsup et al 2004).

Agbabiaka T.B., Guo R., Ernst E. Pelargonium sidoides for acute bronchitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:378-385.

Agosti R., Duke R.K., Chrubasik J.E., Chribasik S. Effectiveness of Petasites hybridus preparations in the prophylaxis of migraine: a systematic review. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:743-746.

Arai M., Hayashi A., Sobou M., et al. Anti-angiogenic effect of triterpenoidal saponins from Polygala senega. J. Nat. Med.. 2011;65:149-156.

Bao Z., Guan S., Cheng C., et al. A novel antiinflammatory role for andrographolide in asthma via inhibition of the nuclear factor-kappaB pathway. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med.. 2009;179:657-665.

Brattström A., Schapowal A., Maillet I., Schnyder B., Ryffel B., Moser R. Petasites extract Ze 339 (PET) inhibits allergen-induced Th2 responses, airway inflammation and airway hyperreactivity in mice. Phytother. Res.. 2010;24:680-685.

Cáceres D.D., Hancke J.L., Burgos R.A., Sandberg F., Wikman G.K. Use of visual analogue scale measurements (VAS) to assess the effectiveness of standardized Andrographis paniculata extract SHA-10 in reducing the symptoms of common cold. A randomized double blind-placebo study. Phytomedicine. 1999;6:217-223.

Chandrasekaran C.V., Gupta A., Agarwal A. Effect of an extract of Andrographis paniculata leaves on inflammatory and allergic mediators in vitro. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2010;129:203-207.

Chicca A., Raduner S., Pellati F., Strompen T., Altmann K.H., Schoop R., et al. Synergistic immunomopharmacological effects of N-alkylamides in Echinacea purpurea herbal extracts. Int. Immunopharmacol.. 2009;9:850-858.

Fazio S., Pouso J., Dolinsky D., et al. Tolerance, safety and efficacy of Hedera helix extract in inflammatory bronchial diseases under clinical practice conditions: a prospective, open, multicentre postmarketing study in 9657 patients. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:17-24.

Fleming R.M. Safety of ephedra and related anorexic medications. Expert Opin. Drug Saf.. 2008;7:749-759.

Luna L.A.Jr., Bachi A.L., et al. Immune responses induced by Pelargonium sidoides extract in serum and nasal mucosa of athletes after exhaustive exercise: Modulation of secretory IgA, IL-6 and IL-15. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:303-308.

Michaelis M., Doerr H.W., Cinatl J.Jr. Investigation of the influence of EPs(®) 7630, a herbal drug preparation from Pelargonium sidoides, on replication of a broad panel of respiratory viruses. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:384-386.

Modarai M., Gertsch J., Suter A., Heinrich M., Kortenkamp A. Cytochrome P450 inhibitory action of Echinacea preparations differs widely and co-varies with alkylamide content. J. Pharm. Pharmacol.. 2007;59:567-573.

Poolsup N., Suthisisang C., Prathanturarug S., Asawamekin A., Chanchareon U. Andrographis paniculata in the symptomatic treatment of uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infection: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther.. 2004;29:37-45.

Quang L., Woolf A.D. Past, present, and future role of ipecac syrup. Curr. Opin. Pediatr.. 2000;12:153.

Scholey A.B., Tildesley N.T., Ballard C.G., et al. An extract of Salvia (sage) with anticholinesterase properties improves memory and attention in healthy older volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2008;198:127-139.

Shah S.A., Sander S., White C.M., Rinaldi M., Coleman C.I. Evaluation of echinacea for the prevention and treatment of the common cold: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis.. 2007;7:473-480.

www.thorne.com. Astragalus membranaceus. Monograph. Altern. Med. Rev. 2003;8:72-77.

Vlachojannis J.E., Cameron M., Chrubasik S. A systematic review on the sambuci fructus effect and efficacy profiles. Phytother. Res.. 2010;24(1):1-8.

Woelkart K., Linde K., Bauer R. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Planta Med.. 2008;74:633-637.

Anesini C., Werner S., Borda E. Effect of Tilia cordata Mill. flowers on lymphocyte proliferation. Participation of peripheral type benzodiazepine binding sites. Fitoterapia. 1999;70:361-367.

Hegener O., Prenner L., Runkel F., Baader S.L., Kappler J., Häberlein H. Dynamics of beta2-adrenergic receptor-ligand complexes on living cells. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6190-6199.

Holzinger, F., Chenot, J.F., In press. Systematic review of clinical trials assessing the effectiveness of ivy leaf (Hedera helix) for acute upper respiratory tract infections. Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 382789 [Epub 2010 Oct 3]