7 The Psychology of the Aging Spine, Treatment Options, and Ayurveda as a Novel Approach

Introduction and Overview

Wellness and healthy functioning are noticeably disturbed when decompensations in formerly healthy equilibriums occur. At this point, a physician may make a formal diagnosis. Disease and diagnosis, as such, do not denote “disability.” These say little about their functional impact. Signs and symptoms do reflect that some “impairment” has occurred.1 Measuring diminished functioning adds to quantifying decompensations from previous baselines. A brief discussion of these concepts follows.

The concept of “disability” is complex. It denotes an inability to perform or substantial limitations in major life activity spheres: personal, social, and occupational. Disabilities are due to limitations, especially impairments caused by medical and psychiatric conditions (including subjective pain reports) at the level of the whole person, not merely isolated parts or functions. From a functional perspective, “occupational disability” denotes current capacity insufficient to perform one or more material and substantial occupational duties currently demanded and accomplished previously. Last, the term “handicap” denotes an inability measured largely by the socially observable limitations it imposes. Handicap connotes the perception or assumption by an outside observer that the subject or patient suffers from a functional limitation or restriction. The term “handicap” implies that freedom to function in a social context has been lost. In this sense, people with handicaps can benefit from added supports. “Accommodations” that modify or reduce functional demands or barriers are given to them. Opportunities in social contexts, therefore, afford expanded freedom for more activities. In this way, participation restrictions diminish. Intolerance to pain and fatigue are the most frequent reasons patients stop working and claim disability.

Among these, Ayurveda – Traditional Indian Medicine – will be introduced both theoretically and as a range of interventions dealing with the management of aging and orthopedic problems. Ayurveda is a novel treatment option or adjunct among more traditional Western modalities. Given such choices, each person has opportunities to choose proactively, while realistically assessing his or her own specific needs and preferences in selecting healthcare. Different approaches may complement one another or be used integratively. In an available framework of rational and diverse treatment options, choices grounded in scientific evidence and trusted traditions may serve as a basis for good, well-rounded clinical care.2,3

Western Perspectives on the Psychology of Aging

A new conceptual paradigm called the biopsychospiritual model4 has recently been advanced. This enriched perspective recognizes the integral nature of body, mind, and spirit and includes such considerations as sacredness of life, refinement of consciousness, and the deepening fruitfulness that a proactive life may take over the lifespan. Profound respect for life and a renewed humane outlook underlie this approach. These considerations have pragmatic value. They can result in a sense of self-empowered creativeness that engenders the rational therapeutic optimism so essential to functional generativity across life’s chronological thresholds and challenges.

Western Perspectives on Managing the Aging Process

Psychiatry offers help in its treatments to reduce anxiety, depression, and help modulate the impact of stress. Managing the mind through various types of psychotherapies helps enhance generativity. This, in turn, fosters health enthusiasm, productivity, a meaningful life, supportive relationships, and minimizes stagnation. Psychopharmacological interventions complement psychotherapies.

Ayurveda: Traditional Indian Medicine

Introducing Ayurveda, with its almost 6,000 years of prehistory, history, and development, in a few paragraphs is a formidable task. In order not to misrepresent or oversimplify this complex edifice of ideas, the following schematic outline is presented. Only the outer edges of Ayurveda’s Weltanschauung (German), darshana (Sanskrit), or worldview can be addressed in this brief primer.4

The history and development of Ayurveda reputedly spans 6,000 years, for most of which time, only an oral tradition existed. When the sacred scriptures of ancient India emerged in the Vedic period (circa 3,000 BC to 600 BC) in the four Vedas – Rig, Sama, Yajur, and Atharva, Ayurveda gradually became formally organized. Its three great fathers, in the respective foundational texts that bear their names, later codified it: Charaka Samhita (c. 1,000 BC), Sushruta Samhita (c. 660 BC and supplemented by Nagarjuna c. AD 100), and Asthanga Sangraha of Vagbhata (c. AD 7th century).5,6,7

Fundamental Ayurvedic propositions include the following: the Five Great Gross Elements (Pancha Mahabhutanis) – Ether, Air, Fire, Water, and Earth; the biological doshas –Vata, Pitta, Kapha; Agni – how cells and tissues process molecules, the digestive and assimilative processes, metabolic rate, and cellular transport mechanisms; the seven bodily tissues (sapta dhatus) – plasma, blood, muscle, fat, bone, marrow and nerve tissue, and reproductive tissue; Ojas – immunity, stress modulation, and resistance to disease; Prakruti – an individual’s “biopsychospiritual” constitutional type; Samprapti – pathogenesis; Vikruti – specific disease syndromes in an individual; Ahara – diet; Vihara – lifestyle; Dravyaguna Shastra – pharmacognosy, pharmacology, materia medica, and therapeutics.

Ayurvedic Perspectives on Managing the Aging Process with Respect to Bone

Bone (asthi) is considered one of the seven major tissues composing the material substance of the physical body (sharira). Bone, its membranous coverings (purishadhara kala), articular joints (sandhi), cartilage (tarunashti), and channels of circulation (asthivaha srotas) are major components of the skeletal system. It is primarily derived from three of the Five Great Gross Elements or principles of organization of matter: Earth and Water (Kapha dimension) and Air (Vata dimension). The Sanskrit term asthi means to stand and endure. A major function of bone is support (dharana); bone also acts to protect vital organs and contributes to the shape and form of the body. Vagbhata (c. AD 700) asserts that bone tissue nourishes nerve and marrow tissue (majja dhatu) in critical ways. In terms of doshas, the substance of bone is essentially of Kapha origin. Two subspecies of Kapha are dominant: Avalambaka Kapha, centered in the thorax and vertebral column, and Shleshaka Kapha, situated in joint fluids and apposing structures such as disks and articular surfaces.

Ayurveda’s three foundational texts, Charaka Samhita, Sushruta Samhita, and Asthanga Sangraha of Vagbhata describe pain syndromes related to bone. In addition, a later work, Madhava Nidana (c. AD 650–950)8 introduced the conceptualization of amavata. This toxic Vata condition has much in common with rheumatoid arthritis, and is marked by inflammation and edema.

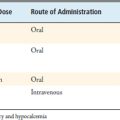

Ayurvedic treatments typically begin with procedures that target Ama detoxification and optimize the digestive process. In the context of a Vata-pacifying diet, various detoxifying herbs are used. These may include triphala (Emblica officinalis, Terminalia chebula, and Terminalia belerica), turmeric (Curcuma longa), guduchi (Tinea cordifolia),9 castor oil (Ricinus communis), and ginger (Zingiber officinale). Substances that reduce inflammation include Boswellia (Boswellia serrata) and guggul (Commiphora mukul). In osteoarthritis (Sandhigatavata) where degeneration is prominent, ashwaganda (Withania somnifera) and other highly tonic/nutritive herbs are given after a period of stabilization to promote healing and rebuild tissue. Turmeric (haridra in Sanskrit; jiang huang in Chinese) is used in Ayurveda and Chinese medicine to stimulate blood flow and reduce inflammation. Single herbs and compounds with several herbs are typically given.

Ayurvedic physicians recommend ghee, very modest amounts of highly-clarified butter, to facilitate the assimilation and efficacy of herbs. Ghee or butter oil is regarded as a medicine, not similar to ordinary butter with its possible deleterious effects on lipid profiles and cardiovascular system. Ghee has specific therapeutically targeted effects and is an adjuvant and potentiator of other medicinal substances. Ghee contains up to 27% monounsaturated and about 66% short-chain fatty acids along with about 3 % conjugated linoleic acid (CLA). This composition is a beneficial profile. Taken in moderation, ghee demonstrates antioxidant, antimicrobial, anticarcinogenic, and lipid nondysregulation properties.10 Ghee contains a fat-soluble fraction of vitamin K, K-2, or meanquinone-7 or menaquinone-7 (MK-7). K-2 produces gamma-carboxylated osteocalcin and facilitates the incorporation of calcium into bone matrix. In Japan, MK-7 is highly concentrated in a soybean food, “natto,” fermented by Bacillus subtilis. People with osteoporosis and those who might benefit from natto’s significant blood-thinning properties eat this food.

In addition to diet and herbs, oils specially prepared for therapeutic massage (abhyanga) coupled with topical moist heat fomentation (swedhana) are a regular part of treatment protocols. Such intermittent mild temperature elevations aid in infection control. Commonly used therapeutic massage oils include sesame, castor, and a special compound called Mahanarayan. Efficacy lies in the mobilization of contracted tissues, alleviating pain, and reducing swelling and induration. Oil massage is a highly regarded treatment intervention, and one that patients perceive as helpful and valuable. In India, specially prepared herbalized oil enemas (basti) are also a regular part of specialized anti-Vata treatments.

1. Ninivaggi F.J. Malingering. In Sadock B.J., Sadock V.A., editors: Kaplan & Sadock’s comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, ed 9, Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2010.

2. Clayton J.J. Nutraceuticals in the management of osteoarthritis. Orthopedics. 2007;30(8):624-629.

3. Khanna D., Sethi G., Ahn K.S., Pandey M.K., Kunnumakkara A.B., Sung B., Aggarwal A., Aggarawal B.B. Natural products as a gold mine for arthritis treatment. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7(3):344-351.

4. Ninivaggi F.J. Ayurveda: a comprehensive guide to traditional Indian medicine for the west. Westport, Conn: Praeger; 2008.

5. Kaviratna A.C., Charaka Samhita, 4 vols, Girish Chandra Chakravarti Deva Press, Calcutta, 1902–1925.

6. Trikamji J., Ram N. Sushruta Samhita of Sushruta. Varanasi, India: Chaukhambha Orientalia; 1980.

7. Murthy K.R.S. translator:Ashtanga Samgraha of Vagbhata. Varanasi, India: Chaukhambha Orientalia; 2005.

8. Murthy K.R.S. translator: Madhava Nidanam. Varanasi, India: Chaukhamba Orientalia; 1987.

9. Panchabhai T.S., Kulkarmi U.P., Rege N.N. Validation of therapeutic claims of Tinospora cordifolia: a review. Phytother Res. 2008;22(4):425-441.

10. Sharma H. Butter oil (ghee) – myths and facts. Ind J Clin Pract. 1990;1(2):31-32.