CHAPTER 9 The Psychiatric and Psychological Evaluation of the Chronic Pain Patient: An Algorithmic Approach

INTRODUCTION

The goals of psychiatric and psychological assessment of the chronic pain patient (CPP) are:1 (1) diagnosis of psychiatric pathology, (2) prediction of behavior, (3) decision-making for treatment planning, (4) prediction of response to treatment, and (5) evaluation of change of symptoms (outcome). Of these goals, the most important is that of decision-making for treatment planning. This goal, however, cannot be accomplished without a clear delineation of the current psychiatric and psychological problems of the CPP. It is unfortunate that the above goals do not lend themselves readily to the formulation of a problem list out of which a problemoriented psychiatric and psychological treatment plan can be readily developed. The usual chapter on the psychiatric and psychological evaluation of the CPP ignores this issue. Generally, a generic global approach to the evaluation of the CPP is touted and presented rather than the problem-oriented approach. It is therefore the goal of this chapter to present a problem-oriented approach to the psychiatric and psychological evaluation of the CPP, utilizing the concept of ‘comorbidity.’ In addition, as there is very little information on the psychiatric and psychological evaluation of the patient with acute or subacute pain, these areas will not be addressed in this chapter. Finally, some chapters on the psychiatric and psychological evaluation of the CPP include the evaluation of pain and function. As these two topics are huge in scope, they will not be addressed in this chapter.

PSYCHIATRIC, PSYCHOLOGICAL, AND SOMATIC COMORBIDITIES ASSOCIATED WITH CHRONIC PAIN

A ‘comorbidity’ has been defined as any distinct clinical entity that exists or occurs during the clinical course or treatment of the index disease.2 In this case, the index disease is chronic pain. Treatment of the index disease can be complicated by the comorbid disease or condition, which can interfere with or increase the difficulty of treatment, resulting in worse prognosis for the index disease.3 Thus, ‘comorbidity’ can lead to spurious medical outcomes and false research information in reference to the index disease. Comorbidity is a psychiatric concept because it has been noted for years that psychiatric illnesses are comorbidly associated with each other.3 However, it is only recently that the ‘comorbidity’ concept was applied to CPPs.4–10 Thirty years of research and clinical experience have crystallized into a body of knowledge, which can, with relative certainty, delineate which ‘comorbidities’ are found in the ‘usual’ chronic pain patient (CPP). This issue is important because it then simplifies the psychiatric and psychological examination of the CPP. Screening questions can be asked for the comorbidities usually found and/or specific tests can be given to measure these comorbidities. Application of the comorbidities concept also facilitates a ‘problem-focused’ approach to the treatment of the CPP.

Three major groups of comorbidities are usually associated with chronic pain (CP): (1) psychiatric problems meeting the threshold for diagnosis utilizing the Psychiatric Diagnosis And Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV);11 (2) psychological problems which may not meet the threshold for diagnosis according to the DSM-IV, or which are not diagnosable by the DSM-IV system, e.g. conflicts over abuse (sexual or physical), etc.; and (3) somatic comorbidities, which may or not have a behavioral component.

CPPs usually demonstrate significant psychiatric comorbidity. In an early study, Fishbain et al.12 reported that in a large group of CPPs treated at a pain facility, only 5.2% had no DSM-III (the system used at that time) diagnosis on Axis I where state diagnoses, such as anxiety and depression, are coded. Thirty-four point nine percent had one diagnosis, but 59.9% had more than one diagnosis on Axis I.12 Thus, overall, 94.8% had psychiatric comorbidity, while approximately 60% had complex comorbidity (more than one diagnosis). The most common/frequent comorbidities usually found in CPPs are presented in Table 9.1 in order of decreasing frequency.

Table 9.1 Psychiatric Comorbidities on Axis I of the DSM-IV Usually Found in CPPs in Order of Frequency4,5,7,10,12–15

Psychological comorbidities are also frequently associated with chronic pain (CP). These behavioral comorbidities develop because of the environmental response of the patient developing CP and are situation dependent. For example, the usual CPP finds himself/herself with what he/she perceives as a medical problem for which physicians cannot make an appropriate diagnosis and/or develop a cure.16 Meanwhile, this illness is associated with significant disability, which has tremendous impact on the CPP’s life, yet physicians are not able to assign an appropriate impairment which matches the disability.17 The CPP is often suspected or accused of having a drug problem, or faking,18,19 or having a psychiatric problem in order to try to assign an explanation for the mismatch between the observed medical impairment and the disability.9,20 As a result, the CPP gets into conflict with the insurance and medical systems and winds up in litigation. The litigation process is extremely stressful, often leading to economic uncertainty for the CPP until settlement. All of these diverse environmental problems can increase stress, and in fragile individuals leads to psychiatric comorbidity. The psychological comorbidities usually found in CPPs are presented in Table 9.2. This table is subdivided into 12 major areas which will be discussed below.

Table 9.2 Psychological Comorbidities Usually Found in CPPs4,21–29

The somatic comorbidities usually found in CPPs are presented in Table 9.3. Studies of fatigue, headache, sleep, and memory/concentration problems indicate that these comorbidities are extremely common within CPPs.4,30 Because the group of comorbidities usually present as symptoms and signs which interfere with function, the presence of any of these increases the difficulty in rehabilitating the CPP.30 Some of the comorbidities fall under the rubric of medically unexplained symptoms. As such, they become the purview of the psychiatrist or psychologist. Because these comorbidities are usually not evaluated by the psychiatrist or psychologist, they are only presented here for the sake of completeness.

Table 9.3 Somatic Comorbidities Usually Found in CPPs4,8,30–39,40,41

| Headache |

| Fatigue |

| Sleep |

| Sexual dysfunction |

| Memory/concentration problems |

| Irritable bowel syndrome |

| Nonorganic physical findings |

| Somatization |

| Greater disability versus medical impairment |

The comorbidities presented in Tables 9.1 and 9.2 will be utilized below in a problem-oriented fashion to suggest an approach to the psychiatric and psychological evaluation of the CPP. This in turn lends itself to the algorithmic approach.

PAPER AND PENCIL TESTS TO BE UTILIZED TO COMPLEMENT THE PSYCHIATRIC OR PSYCHOLOGICAL PAIN INTERVIEW

Rating scales, multiaxial inventories or personality tests

At the present time, the pain clinician is confronted by a bewildering choice of paper and pencil tests alleged to measure some behavioral aspect which may be important to pain treatment. Before a choice can be made, however, that clinician should understand the concept of State and Trait and the differences between paper/pencil tests in reference to the concept of State–Trait. State psychiatric disorders have the following characteristics:42 they are a result of plasticity in the biobehavioral systems which allows for reversibility; they are time limited and usually respond to medications or other somatic treatments; examples of these disorders are depression and anxiety; and these disorders are coded on Axis I of the DSM-IV. On the other hand, Trait psychiatric disorders have the following characteristics:42 they are a function of plasticity which is organization and therefore does not allow for much reversibility; Trait disorders are dysfunctional personality qualities which individuals tend to develop and carry throughout life and which manifest as predictable patterns of interaction and response to stress; these disorders respond better to psychosocial treatment rather than medications; and they are coded on Axis II of the DSM-IV.

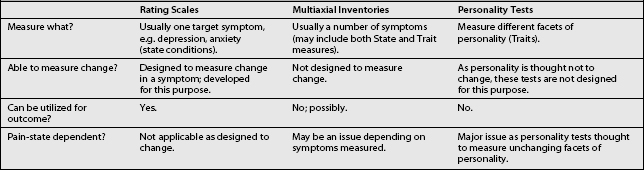

Presently, the available behavioral paper/pencil tests can be divided into three rough groupings: rating scales, multiaxial inventories, and personality tests. Characteristics of each type of test are presented in Table 9.4. It is to be noted from Table 9.4 that rating scales usually measure State conditions and are therefore designed to measure change (outcome), while personality tests are designed to measure Traits and are therefore not designed to change, as it is expected that personality structure will not change. Multiaxial inventories, on the other hand, usually are a mixture of questions for State–Trait problems, and as such it is unclear whether the measurement of change is an intended consequence of the development of the test. It is to be noted that this mixing of State and Trait items in some test instruments has been described by some psychologists as ‘leading to results which are confusing and difficult to interpret.’43

Recently, however, another problem has been noted in reference to the State–Trait measurement issue and pain. Pain can be considered to be a very powerful State problem. It appears that there is significant evidence44 that the presence of pain as a State phenomenon affects the measurement of Trait (personality characteristics). In other words, the personality structure of the individual as measured by some personality tests can appear to be more pathological in the presence of pain. This finding is less clear for the multiaxial inventories,44 but because of their nature can still be a problem.

SCREENING QUESTIONS AND MEASUREMENT APPROACHES FOR THE PSYCHIATRIC COMORBIDITIES

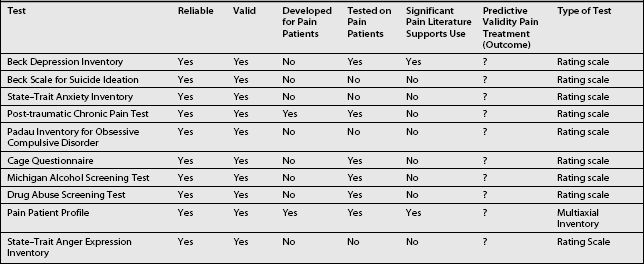

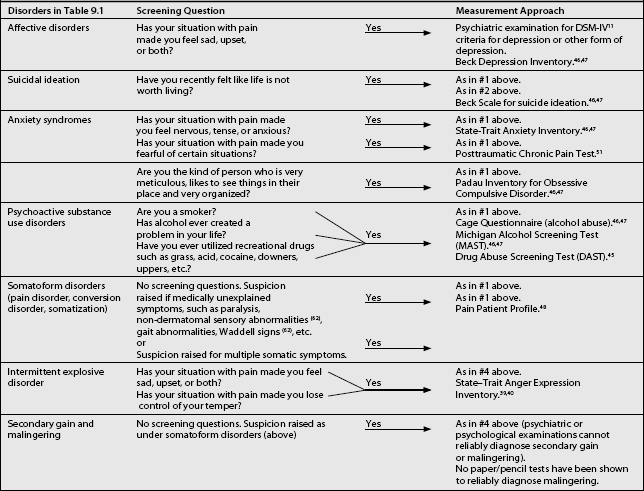

Table 9.5 presents a series of screening questions for the psychiatric comorbidities frequently found in CPPs. In addition, this table presents what are currently thought to be the most useful paper/pencil tests for these comorbidities. The paper and pencil tests can be administered if the CPP answers affirmatively to the screening question. As an alternate approach, the pain clinician can request a psychiatric or psychological consultation if the screening questions are answered in the affirmative. Some of the suggested tests in Table 9.5 deserve comment (below). Characteristics of these tests in reference to chronic pain will be found in Table 9.6.

Table 9.5 Screening Questions and Measurement Approaches for the Psychiatric Comorbidities from Table 9.1

The Beck depression inventory (BDI) is a 21-item, self-report questionnaire relating to depression.46,47 It was developed for psychiatric patients, but has been utilized and written about extensively in reference to CPPs. As it is a rating scale, it is an excellent tool to measure improvement. Unfortunately, because of its focus on somatic symptoms (fatigue, sleep, concentration), which are frequently found in CPPs (Table 9.3), it will overestimate the severity of depression. As an example, the cutoff score for being depressed in physically healthy individuals is 10. A recent study exploring the predictive validity of the Beck in CPPs found the optimal cutoff score to be 21.48 However, the BDI does have a significant proportion of items for cognitive symptoms of depression versus other depression rating scales.49 As such, it does not give greater weight to somatic symptoms versus other rating scales. Its use is therefore recommended.

The Beck scale for suicide ideation46,47 is designed to measure current suicidal ideation. It is a 21-item scale which has been shown to have significant correlation with the BDI. However, it has been shown not to have predictive validity for suicide completion. It was developed and tested in psychiatric patients and has not had wide use in CPPs. However, it may have some utility in CPPs who voice suicidal ideation, and as it is a rating scale, it can be utilized to measure improvement in suicidal ideation.

The State–Trait46,47 anxiety inventory is a 40-item self report rating that differentiates between State anxiety, a temporary condition experienced by some individuals, and Trait anxiety, the general chronic anxiety experienced by some individuals. Thus, it evaluates how likely an individual is to feel anxiety (Trait), and how anxious the individual feels at the moment (State). It has good correlation with other widely used anxiety scales. However, it has not been utilized widely in CPPs. As such, its reliability and validity here have not been determined.

Recent reviews have concluded that the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in CPPs has been underestimated.50 Although there are a number of tools available that are developed around the DSM-IV criteria for this diagnosis, none of these is specific to the CPP. The Post-traumatic Chronic Pain Test51 has been specifically developed for use in CPPs and as such is recommended.

CPPs may suffer from subclinical obsessive-compulsive disorders. This has now been termed obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder (OCSD).52 A number of psychiatric disorders, such as body dysmorphic disorder, anorexia nervosa, binge eating, hypochondriasis, sexual compulsions, pyromania, kleptomania, trichotillomania, compulsive buying, pathological gambling, and some self-injurious behaviors appear to demonstrate some obsessive traits and are therefore included in OCSD disorders. The OCSD patients utilize the types of mechanisms and behaviors often noted in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). As such, these mechanisms and behaviors make the index disorder, e.g., gambling, worse and more difficult to treat. At issue, then, is whether these types of mechanism operate in some somatizing disorder such as pain disorder. The features of OCSD and OCD overlap in many respects, including demographics, repetitive intrusive thoughts or behaviors, comorbidity, and etiology. Most importantly, it appears that this group of disorders responds preferentially to antiobsessional drugs, such as clomipramine and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), e.g. fluvoxamine.52,53 There have been no treatment studies utilizing the OCSD concept for pain disorders. However, a number of cases have been published.53 The author has reported15 on the positive response to antiobsessional agents in three cases of chronic atypical facial pain. Recently, there has also been a report of positive response in two patients with schizophrenia and chronic pain to clomipramine.40 This limited evidence indicates that perhaps CPPs with ‘non-specific’ pain and prominent obsessive-compulsive components should be treated with an SSRI at the first opportunity. Thus, it becomes important to identify CPPs who may have prominent OCD traits. As such, the use of the Padau Inventory for OCD is recommended.46,47 However, it is to be noted that this inventory has not been utilized in CPPs.

Multiple somatic symptoms are allegedly found frequently in CPPs. These raise the suspicion of somatization. Historically, somatization has been measured by the MMPI or the SCL-90. However, researchers have argued that these instruments are sensitive to current somatization rather than longstanding somatization traits.54 As such, the Pain Patient Profile55 test is recommended. This inventory measures somatization and has been normed on CPPs.

SCREENING QUESTIONS AND MEASUREMENT APPROACHES FOR THE PSYCHOLOGICAL COMORBIDITIES

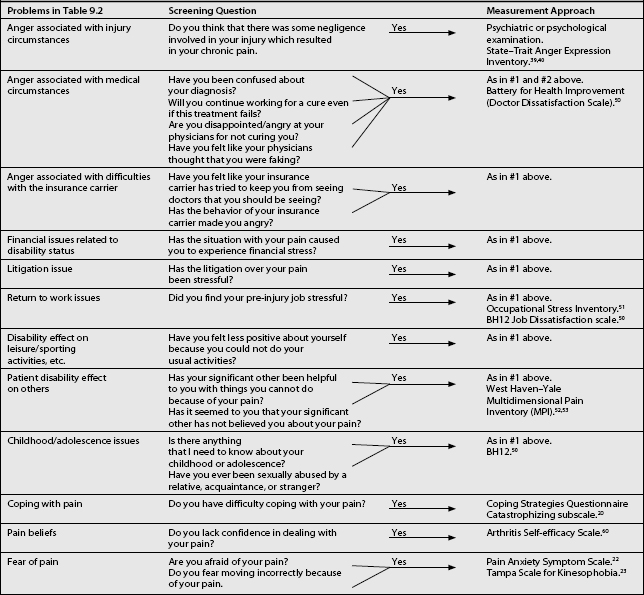

Screening questions and suggested tests for the psychological comorbidities are presented in Table 9.7. Some of these comorbidities and measurement approaches require comment (below).

Table 9.7 Screening Questions and Measurement Approaches for the Psychological Comorbidities from Table 9.2

As noted above, CPPs are subjected to a number of significant stressors. These stressors in some predisposed CPPs lead to the development of severe anger.56,57 Greater levels of anger were shown to be associated with poorer treatment outcome from a pain management program.58 To measure this concept the State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory46,47 is recommended. This inventory is not pain specific, but has been utilized in CPPs. Another anger inventory is the battery for Health Improvement.59 This is an inventory that contains a doctor dissatisfaction scale, which makes it unique. In addition, it has been standardized on patients in rehabilitation, with a significant percentage of those experiencing chronic pain. Its use, especially to measure doctor dissatisfaction, is therefore recommended.

Chronic pain rehabilitation programs emphasize return to work. However, recent pain research has demonstrated that pre-injury job stress is predictive for return to work post pain facility treatment.27 As such, the measurement of pre-injury job stress can identify perceptions about work, which can have an impact on rehabilitation and can thus become the target of occupational rehabilitation. For this purpose, the Occupational Stress Inventory60 is recommended. This inventory has satisfactory reliability and validity in CPPs. Another scale that may be useful in such instances is the BH1259 as it has a job dissatisfaction scale. This scale assesses angry feelings directed toward the workplace. These feelings are further broken down into negative attitudes towards the company, supervision, coworkers, and the job itself. This scale has established validity and reliability with patients in physical rehabilitation.

Significant others around the CPP can respond in one of three ways to the CPP’s pain behaviors: in a supportive fashion; rejecting fashion; and oversolicitous fashion. Psychological theory holds that oversolicitousness can reinforce pain behavior. On the other hand, the rejecting spouse can lead to stress. The West Haven–Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory61,62 has a solicitousness scale and also taps the rejecting concept. It has been developed for CPPs. As such, it is recommended to measure these concepts.

For a number of years a series of research reports have suggested that there is a greater proportion of victims of sexual abuse in CPP populations than in the general population. A recent review of this literature has, however, concluded that the evidence does not demonstrate a causal relationship between childhood abuse and chronic pain.41 However, the pain clinician may wish to investigate this issue. Two screening questions are suggested for this problem (see Table 9.7) and no questionnaire is recommended. The second screening question, ‘Have you ever, etc.,’ has been shown to have significant reliability as a self-report measure63 and is therefore recommended after the initial open-ended question. If the clinician wishes to investigate this issue further, the BH1259 has a Survivor of Violence scale. This scale assesses a history of physical and sexual abuse, occurring both in childhood and adulthood. The scale was also normed on chronic pain patients.

Coping can be defined as a purposeful effort to manage or mitigate the negative impact of stress.64 The pain literature has been concerned with problem-focused coping strategies to manage pain where coping has been seen as either active or passive.65 Active coping strategies are attempts by the CPP to obtain some control over the pain by using his/her resources, e.g. using relaxation techniques, etc.65 Passive coping strategies, on the other hand, indicate a reliance on external agents for pain control, e.g. medications, etc.65 The Copies Strategies Questionnaire23 was developed on CPPs and contains the catastrophizing scale. This scale has been shown to predict poor treatment outcome if elevated.66 As such, this scale is recommended to measure this concept.

Pain beliefs is another important concept in the pain literature as it relates to how the pain is viewed. Pain beliefs appear to be important because fear/avoidance beliefs have been shown to predict functional disability.67 Patient confidence (self-efficacy) in handling pain can be assessed via the Arthritis Self-efficacy Scale.68 In addition, CPPs may be anxious about their pain and fear it. These concepts can be evaluated via the Pain Anxiety Symptom Scale25 and the Tampa Scale for Kinesophobia.26 Data obtained through these inventories can identify target behaviors, which can then become the focus of intervention.

The final issue relates to the assessment of personality in CPPs. Historically, in CPPs this has been done utilizing the MMPI or the SCL-90. Although there are numerous studies attempting to predict pain facility treatment outcome with these personality assessment tools, the research is equivocal. To date, it is unclear whether these tools can serve this purpose, with the majority of researchers claiming that they cannot. In addition, as pointed out above,44 there are major problems with these tools in reference to State–Trait issues. As such, the use of these inventories in CPPs is to be discouraged.

1 Turk DC, Rudy TE, Sorkin BA. Neglected topics in chronic pain treatment outcome studies: determination of success. Pain. 1993;53:3-16.

2 Feinstein A. The pre-therapeutic classification of comorbidity in chronic disease. J Chronic Dis. 1970;13:455.

3 Merikangas KR, Gelernter CS. Comorbidity for alcoholism and depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1991;13:613-631.

4 Fishbain DA. Psychiatric and psychological problems associated with chronic pain. Primary Care Psychiatry. 1997;3:75-81.

5 Fishbain DA. The association of chronic pain and suicide. Sem Clin Neuropsychiatry. 1999;4(3):221-227.

6 Fishbain DA, Steele-Rosomoff R, Rosomoff HL. Drug abuse, dependence, and addiction in CPPs. Clin J Pain. 1992;8:77-85.

7 Fishbain DA, Cutler B, Rosomoff H, et al. Comorbidity between psychiatric disorders and chronic pain. Curr Rev Pain. 1998;2:1-10.

8 Fishbain DA, Cutler R, Cole B, et al. International headache society headache diagnostic patterns in pain facility patients. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:78-93.

9 Fishbain DA, Cole B, Cutler RB, et al. A structured evidence-based review on the meaning of non-organic physical signs: Waddell signs (W.S.). Pain Med. 2003;4(1):51-62.

10 Fishbain DA. Approaches to treatment decisions for psychiatric co-morbidity in the management of the chronic pain patient. Medl Clin N Am. 1999;33(3):737-760.

11 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

12 Fishbain DA, Goldberg M, Meagher BR, et al. Male and female CPPs categorized by DSM-III psychiatric diagnostic criteria. Pain. 1986;26:181-197.

13 Fishbain DA, Goldberg M, Steele-Rosomoff R, et al. Case report: completed suicide in chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 1991;7:29-36.

14 Asmudson GJ, Norton GR, Jacobson SJ. Social, blood/injury, and agoraphobic fears in patients with physically unexplained chronic pain: Are they clinically significant? Anxiety. 1988;2:87-95.

15 Fishbain DA, Trescott J, Cutler B, et al. Do some CPPs with atypical facial pain overvalue and obsess about their pain? Psychomatics. 1993;34(4):355-359.

16 Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Steele-Rosomoff R, et al. The problem-oriented psychiatric examination of the CPP and its application to the litigation consultation. Clin J Pain. 1994;10:28-51.

17 Fishbain DA. Pain and psychopathology. In: Fogel BS, Schiffer RB, Rao SM, editors. Neuropsychiatry. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:443-483.

18 Fishbain DA. Secondary gain concept: definition problems and its abuse in medical practice. Am Pain Soc J. 1994;3:264-273.

19 Fishbain DA, Rosomoff HL, Cutler RB, et al. Secondary gain concept: A review of the scientific evidence. Clin J Pain. 1995;11:6-21.

20 Fishbain DA, Cutler R, Rosomoff HL, et al. Chronic pain disability exaggeration/malingering research and submaximal effort research. Clin J Pain. 1999;15(4):244-274.

21 Glenton C. Chronic back pain suffers, striving for the sick role. Social Sci Med. 2003;57(11):2243-2252.

22 Pawlicki RE. A neglected issue: the family of the CPP. Am Pain Soc Bull. 1992; Oct/Nov:5-6.

23 Rosenstiel AK, Keefe FJ. The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain. 1983;17:33-44.

24 Druley JA, Stephens MA, Mortire LM, et al. Emotional congruence in older couples coping with wives’ osteoarthritis: exacerbating effects of pain behavior. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(3):406-414.

25 Admundson GJG, Norton GR, Allerdings MD. Fear and avoidance in dysfunctional chronic back pain patients. Pain. 1997;69:231-236.

26 Vlaeyen JWS, Kolke-Snijders AMJ, Boeren RGB, et al. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain. 1995;62:363-372.

27 Fishbain DA, Cutler R, Rosomoff HL, et al. The prediction of CPP ‘intent,’ ‘discrepancy with intent’ and ‘discrepancy with non-intent’ for return to work post pain facility treatment. Clin J Pain. 1999;61:165-175.

28 Raphael NG, Spatz Widon C, Lange G. Childhood victimization and pain in adulthood: a prospective investigation. Pain. 2001;92:283-293.

29 Raphael KG, Chandler H, Ciccone DS. Is childhood abuse a risk factor for chronic pain in adulthood? Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2004;8:99-110.

30 Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Street JH, et al. Predicting poor outcome for back pain seen in primary care using patients’ own criteria. Spine. 1996;21:2900-2907.

31 Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Cole B, et al. Is pain associated fatigue responsive to multidisciplinary pain facility treatment. Accepted for publication, Pain Med

32 Fishbain DA, Cutler B, Cole B, et al. Is pain fatiguing? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med. 2003;4(1):51-62.

33 Atkinson JH, Ancoli-Israel S, Slater MA, et al. Subjective sleep disturbance in chronic back pain. Clin J Pain. 1988;4:225-232.

34 Menefee LA, Cohen MJ, Anderson BA, et al. Sleep disturbance and nonmalignant chronic pain: a comprehensive review of the literature. Pain Med. 2000;1(2):156-172.

35 Hart RP, Martelli MF, Zasler ND. Chronic pain and neuropsychological functioning. Neuropsychol Rev. 2000;10:131-149.

36 Williams AN, Hill P, Gunary R, et al. Sexual difficulties of CPPs. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(2):138-145.

37 LaBan MM, Burk RD, Johnson EW. Sexual impotence in men having low back syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1966;45:715-723.

38 Lipowski ZJ. Somatization: the concept and its clinical application. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:1358-1366.

39 Turk DC, Matyas TA. Pain-related behaviors: communication of pain. Am Pain Soc J. 1992;1:109-111.

40 Verdugo RJ, Ochoa JL. Reversal of hypesthesia by nerve block, or placebo: a psychologically mediated sign in chronic pseudoneuropathic pain patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1998;65(2):196-203.

41 Moriwaki K, Yugae O, Nishioka K, et al. Reduction in the size of tactile hypesthesia and allodynia closely associated with pain relief in patients with chronic pain. Progress Pain Research Management. 1994;2:819-830.

42 Extein I, Bowers M. State and trait in psychiatric practice. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(5):690-693.

43 Phillip AE. Psychometric changes associated with response to drug treatment. Brit J Social Clin Psychol. 1971;10:138-143.

44 Fishbain DA, Cole B, Cutler RB, et al. Does the presence of chronic pain as a state phenomenon affect the measurement of personality characteristics (traits)? A structured evidence based review. Pain Med. accepted for publication.

45 Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7:363-371.

46 Ishak WW, Burt T, Sederer LI, editors. Outcome measurement in psychiatry, a critical review. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002.

47 Sajatovic M, Ramirez LF. Rating scales in mental health. Hudson, OH: Lex-Comp, 2001.

48 Geisser ME, Roth RS, Robinson ME. Assessing depression among persons with chronic pain using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory: a comparative analysis. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:163-170.

49 Marley S, Williams AC, Black S. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Beck Depression Inventory in chronic pain. Pain. 2002;99(1-2):289-298.

50 Sharp TJ. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in chronic pain patients. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2004;8(2):111-115.

51 Muse M, Frigola G. Development of a quick screening instrument for detecting posttraumatic stress disorder in the CPP: construction of the posttraumatic chronic pain test (PCPT). Clin J Pain. 1987;2:151-153.

52 Hollander E. Treatment of obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders with SSRIs. Brit J Psych. 1998;35(S):7-12.

53 Kurokawa K, Tanino R. Effectiveness of clomipramine for obsessive-compulsive symptoms and chronic pain in two patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharm. 1997;17(4):329-330.

54 Keller LS, Butcher JN. Assessment of chronic patient patients with MMPF-2. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991.

55 Pain Patient Profile. Minnetonka, MN: NCS Assessments, 1998.

56 Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Rosomoff HL, et al. Risk for violent behavior in patients with chronic pain: evaluation and management in the pain facility setting. Pain Med. 2000;1(2):140-155.

57 Bruehe S, Burns JW, Chung OY, et al. Anger and pain sensitivity in chronic low back pain patients and pain free controls: the role of endogenous opioids. Pain. 2002;99:223-233.

58 Burns JW, Johnson BJ, Devine J, et al. Anger management style and the prediction of treatment outcome among male and female chronic pain patients. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:105-162.

59 Bruns D, Disorbio JM. Manual for the Battery for Health Improvement 2. Minnetonka, MN: NCS Assessments, 2003.

60 Occupational Stress Inventory. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1989.

61 West Haven–Yale Multidimensional Pain (Inventory). Pain Evaluation and Treatment Institute. Pittsburgh, PA: Univ. of Pittsburgh Medical Center, 1995.

62 Bernstein IH, Matthew E, Jaremko, et al. On the utility of the West Haven–Yale multidimensional pain inventory. Spine. 1995;20:956-963.

63 Barbe RP, Bridge JA, Brimaher B, et al. Lifetime history of sexual abuse, clinical presentations, and outcome in a clinical trial for adolescent depression. Clin J Psychiatry. 2004;65(1):77-83.

64 Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, et al. Coping with chronic pain: a critical review of the literature. Pain. 1991;47:249-283.

65 Brown GK, Nicassio PM. Development of a questionnaire for the assessment of active and passive coping strategies in CPPs. Pain. 1987;31:53-64.

66 Coughlan GM, Ridout KL, Williams AC De C, et al. Attrition from a pain management programme. Br J Clin Psychol. 1995;34:471-479.

67 Crombez G, Vlaeyen JW, Heuts PH, et al. Pain-related fear is more disabling than pain itself: evidence on the role of pain-related fear in chronic back pain disability. Pain. 1999;80:329-339.

68 Lorig K, Chastain RI, Ung E, et al. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:37-44.