There are two aspects to manipulation. First, it is an extremely effective form of reflex therapy in many types of pain, a feature that it shares in common with many other methods of physical therapy such as massage, electrical stimulation, and local anesthesia. Second, it is a specific form of treatment for important locomotor system dysfunctions, namely for functionally reversible movement restrictions involving joints and motion segments of the spinal column. And these movement restrictions can be regarded as a model for locomotor system dysfunctions in general.

It soon became clear that treatment of restricted joint movement had its limits and that passive movement restriction in itself involves not only joints but also muscles. It was this recognition of the importance of trigger points (TrPs) and their role in restricted joint movement and in the pathogenesis of locomotor system pain that signaled the next decisive step forward. Indeed, the close inter-relationships between joints and muscles became the starting point for further advances, leading to an improved understanding of active movement and its dysfunctions, and enabling us to identify muscle imbalance and faulty motor patterns.

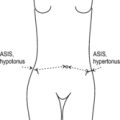

No less important than movement are posture and statics, as demonstrated by the ever-increasing practical significance of excessive static strain in contemporary technological society. In recent years we have benefited immensely from progress in the field of developmental kinesiology made by Vojta & Peters (1992) and Kolář, 1996 and Kolář, 2001 and this now forms the basis of our understanding of upright posture in humans. These insights relate to the co-activation pattern of flexors and extensors in the trunk and of adductors and abductors and of external and internal rotation in the extremities. In addition, we know that the deep stabilizer system operates to maintain the otherwise labile equilibrium of the human body in the sagittal plane. The harmonious associated movement of all soft tissue, including the viscera, is a further important element that should not be forgotten, as demonstrated by the role of active scars in pathogenesis.

Familiarity with all the above aspects is indispensable if we wish to negotiate the uncharted ‘no man’s land’ of dysfunctions devoid of gross pathological changes that occupies the indeterminate borderlands between the traditional specialist disciplines of neurology, orthopedics, rheumatology, and physical medicine. We have coined the phrase ‘functional pathology of the locomotor system’ to describe this no man’s land. The most frequent clinical manifestation of this pathology is pain, the symptoms of which include TrPs, hyperalgesic zones, restricted joint movement, and changes in tissue tension.

Manipulative or manual medicine played a major role in these developments not only as the initial step toward ‘functional pathology’, but also because as a form of ‘bloodless surgery’ it called for precise palpatory diagnostic skills. While it is relevant in restricted joint movement, this palpatory diagnostic aspect also serves to enhance understanding of muscle TrPs, of soft-tissue mobility and relative displacement, and ultimately of pathological resistance in the abdominal cavity where active scars are present. In all these changes, the barrier phenomenon is utilized to impart a degree of objectivity to palpatory findings. Only a diagnostic approach that includes all tissues will permit comprehensive therapy that is consistent with the pathogenesis of locomotor system dysfunctions.

For all the importance that has come to be attached to the manipulative treatment of joints, it is only one method among many. Anyone who uses it should never limit themselves to just one method, no matter how effective it may be. The object of treatment is not any single method but the locomotor system and, primarily, its function, and historically this has had no specialist discipline of its own. Today there is a growing tendency to designate this emerging specialty as ‘musculoskeletal medicine’.

We should remind ourselves that locomotor system function is the most complex of all functions in the human body, and this is reflected in the fact that the largest part of the brain is associated with locomotor system function and control. This control is reflected in motor system programs that are designed to implement function: these relate to the locomotor apparatus as a whole, and this explains why dysfunctions only rarely affect a limited part of the locomotor system but usually involve the system as a whole. The clinical expression of this fact is the chain reaction pattern: this phenomenon was initially understood solely in empirical terms although we are now beginning to unravel something of the theoretical background too.

One major difficulty is that although we are familiar from experimental research with the basic neurophysiology of reflex mechanisms at a spinal level up to and including the brainstem, the same cannot be said for those that encourage the co-activation patterns responsible for human upright posture and stability. These are reflex processes that we observe daily when we treat the lower extremities or the trunk and provoke reactions in the cervical region, or conversely when we treat the craniocervical junction and influence function in the pelvic region. Vojta’s developmental kinesiology has provided some insight into these situations: his stimulation techniques demonstrate these reflex patterns in humans in an ‘experimental setting’ as it were.

Advances made in the theoretical field are the prerequisite for understanding the modern-day development of musculoskeletal medicine. The practical point to emerge from the concept of chain reaction patterns is that once the relevant link in the chain has been identified, it is then possible not only to administer treatment with the utmost economy, but also to determine the direction for further therapy and rehabilitation. In this context it has been found that most chain reaction patterns originate in the deep stabilizers of the trunk (which are intimately associated with respiration) and in the feet.

The key role in stability is played by monoarticular muscles which are largely under involuntary control. Dysfunctions of these muscles very often result in intensive chain reaction patterns that manifest themselves as pain due to TrPs and movement restrictions. These lead in turn to faulty movement patterns that create a kind of compensatory stability in which the true stabilization system is no longer operative. After successful activation of the deep stabilizers, it is routinely observed that TrPs and movement restrictions disappear throughout the system as a whole.

Summarized in the proverbial nutshell, the development has been from joint to muscle, and from an accent on mobilization to stabilization, which leads automatically to the release of pathological movement restrictions, provided that these are not caused by viscerovertebral reflex mechanisms or active scars, for example.

Recognition of the importance of muscles and TrPs has not been without consequences for the development of manipulative techniques, and of mobilization in particular. In recent years we have learned to apply neuromuscular techniques that make use of the patient’s own muscles to achieve mobilization. TrP relaxation and mobilization go hand in hand, serving simultaneously also to abolish pain at the attachment point of the tensed muscle. And from these techniques that depend on the active cooperation of the patient it is just a small step to self-treatment: every patient should be assigned a daily program of home exercises tailored specifically to the most recent examination findings. In this way, therapy transitions seamlessly into rehabilitation, with the practitioner functioning merely to monitor progress and suggest corrections.

This trend has also had the effect of bringing a radical change to the relationship between practitioner and patient. In most fields of medicine the unquestioning patient expects to be cured of suffering, whether by drugs, surgery, or miracle. In such situations where the practitioner is the authority figure, the patient is the object and is not required to do anything, and certainly must not ask (annoying) questions. In manual medicine, however, the patient is the subject and, as such, cooperates intelligently at every opportunity even while treatment is in progress, increasingly taking responsibility for self-treatment and responding to advice designed to correct lifestyle errors. If the patient is moved out of the ‘comfort zone,’ so too is the practitioner who has to face up to the difficult problem of psychological motivation. It is illusory to imagine that the function of the locomotor system, the organ of voluntary movement, can be treated successfully without the active involvement of the patient. From the very outset the human factor plays a major role here, as reflected in the intimate hands-on contact established with the patient.

At a time when apparatus-based techniques have come increasingly to the fore, we must continue to rely on our hands and eyes as we strive to acquire those skills that modern medicine has largely neglected in favor of sophisticated (and costly) technology. Only the skilled human hand is capable of sensing the patient’s reactions and of adapting to the patient’s needs. The function of the locomotor system is an expression of personality and therefore a personal relationship between patient and practitioner is vital. The logical conclusion to be drawn is that manipulation has its place within the framework of physical medicine and rehabilitation, the goal of which is to restore function using physiological methods.

Attainment of this goal is possible only in a team, the members of which are the physician, the physiotherapist and the patient. The role of the physician is to form the diagnosis and, most importantly, to analyze the locomotor system dysfunction. This necessitates close familiarity with the functional approach, and this is as difficult to acquire as a polished manual technique. Because the university education of physicians in mainstream medical schools leaves much to be desired in this respect, intensive efforts are needed to introduce appropriate training for physicians who wish to specialize in musculoskeletal medicine. The treatment itself should then be implemented in consultation with the physiotherapist.

The problem for physiotherapists today is due in no small measure to the fact that their training lacks uniformity. However, one certainty is that the future belongs to physiotherapists who, as a minimum requirement, have completed a full university degree course. This is already largely the case in the Czech Republic; on completion of university studies, the graduate physiotherapist has a greater knowledge of the locomotor system than a physician newly qualified from medical school. By that stage the physiotherapist has also learned how to inspect patients and how to approach them in a hands-on manner, while already possessing a broad understanding of the principles of manipulative therapy. Because it is indispensable for rehabilitation, the functional approach is also more intuitive for the physiotherapist.

The division of labor between physician and physiotherapist will vary considerably, depending on the manual skills of the physician and physiotherapist working together in the same team. The physician may initiate therapy in order to be satisfied about the correctness of the diagnosis and case analysis, but the physician may also delegate therapy to the physiotherapist; however, as physiotherapy proceeds, the physician will need to assess the results so far and then determine any subsequent treatment steps in consultation with the physiotherapist and patient.

It is to be expected that, because of their training, physiotherapists will on average be better prepared than physicians for the practice of manual medicine. Because manipulative therapy moves naturally and seamlessly into rehabilitation where the activity of the patient is crucial, the physiotherapist has an important role to play here. In consultation with the physician, the physiotherapist is also responsible for the application of other physical therapy modalities.

As in the past, so too in the future, the training of physicians and physiotherapists is a decisive factor, with the functional approach being more important than mere cramming of facts, which often simply involves regurgitating what was taught during student days and then forgetting it again. In this respect, too, the physiotherapist has things easier because, as far as the physician is concerned, the functional approach invariably entails a degree of re-learning, and that is always difficult. For practical training purposes, a sufficient number of instructors is essential in order to guarantee high-quality courses. And if participants are to acquire the necessary skills, the trainee-to-instructor ratio should be such that one-to-one tuition is possible. The foundation stone of good technical training is a hands-on approach.

For the reasons enumerated above, it would be highly desirable if the basic principles of musculoskeletal medicine and rehabilitation were introduced into the medical school curriculum, with the objective of awakening interest in this specialist field. Given the enormously high incidence of patients with painful dysfunctions of the locomotor system, every family physician will inevitably come up against these conditions on a daily basis but at present can do little more than prescribe analgesics. They should themselves at least be capable of adequately treating the more straightforward cases. With the easily learned and safe mobilization and soft-tissue techniques in current use, it is also unlikely that the patient will be harmed in any way.

And this brings us to the ultimate goal of our work. The vast majority of painful disorders designated as ‘functional’ and perceived by the patient as organic disease have their origin in the locomotor system and its dysfunctions, which simultaneously give rise to innumerable minor painful ailments. The techniques described in this book are suitable for treating these conditions using physiological methods. It would indeed be a significant contribution to modern medicine as a whole if these methods, which are free from side effects, were to be judiciously brought into play in such patients. Pharmacotherapy, injections, and anesthesia, etc. (with all their side effects) could then be held in reserve, ready to be deployed at the right moment for the more demanding cases where structural changes are generally also present.

The locomotor system, the subject of this book, is the largest and most intricate system in the human body. We need to learn not only to understand its function better but also to take better care of this precious and perfect instrument that we have at our disposal. In an age when we are learning to use ever-more sophisticated mechanical systems, we are losing an intelligent understanding of our own bodies. And this applies particularly to those of us who treat other people: we have learned to utilize increasingly complicated equipment while at the same time neglecting the evidence of our eyes and in particular of our hands, as well as forgetting how to communicate with our patients. However, by comparison with communicating with the patient, observing with our eyes and sensing with our hands, no piece of high-tech equipment is able to yield such a wealth of varied information. And all this is heightened by the capacity for feedback – indeed empathy – between practitioner and patient.