15 The pancreas and spleen

The pancreas

Surgical anatomy

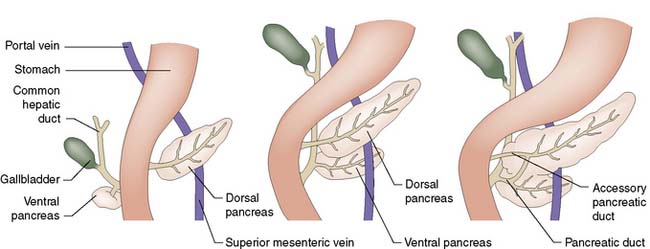

The pancreas develops from separate ventral and dorsal buds of endoderm that appear during the fourth week of fetal life. The ventral pancreas develops in association with the biliary tree, and its duct joins the common bile duct before emptying into the duodenum through the papilla of Vater (Fig. 15.1). During gestation, the duodenum rotates clockwise on its long axis, and the bile duct and ventral pancreas pass round behind it to fuse with the dorsal pancreas. Most of the duct that drains the dorsal pancreas joins the duct draining the ventral pancreas to form the main pancreatic duct (of Wirsung); the rest of the dorsal duct becomes the accessory pancreatic duct (of Santorini) and enters the duodenum 2.5 cm proximal to the main duct. In fetal life, the common bile duct and main pancreatic duct are dilated at their junction to form the ampulla of Vater. In extra-uterine life, only 10% of individuals retain this ampulla, although most retain a short common channel between the two duct systems.

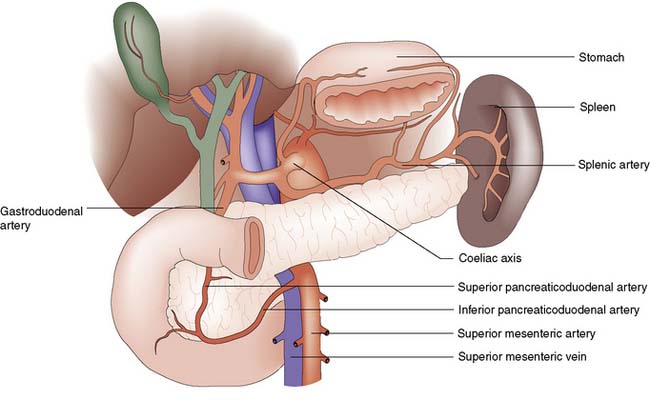

The pancreas lies retroperitoneally, behind the lesser sac and stomach. The head of the gland lies within the C-loop of the duodenum, with which it shares a blood supply from the coeliac and superior mesenteric arteries (Fig. 15.2). The superior mesenteric vein runs upwards to the left of the uncinate process, and joins the splenic vein behind the neck of the pancreas to form the portal vein. The body and tail of the pancreas lie in front of the splenic vein as far as the splenic hilum, and receive arterial blood from the splenic artery as it runs along the upper border of the gland. The intimate relationship of the friable pancreas to these major blood vessels is the reason that bleeding is problematic after pancreatic trauma. The close association between the common bile duct and the head of pancreas explains why obstructive jaundice is so common in cancer of the head of the pancreas, and why gallstones frequently give rise to acute pancreatitis.

Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis

Aetiology

Conditions associated with the development of acute pancreatitis are listed in Table 15.1 – gallstones and alcohol are by far the most important.

| Class | Specific causes |

|---|---|

| Toxic | Alcohol Medication Tropical |

| Genetic | Cystic fibrosis Hereditary pancreatitis SPINK1 mutation |

| Metabolic | Hypercalcaemia Hyperlipidaemia |

| Obstructive |

Gallstone pancreatitis

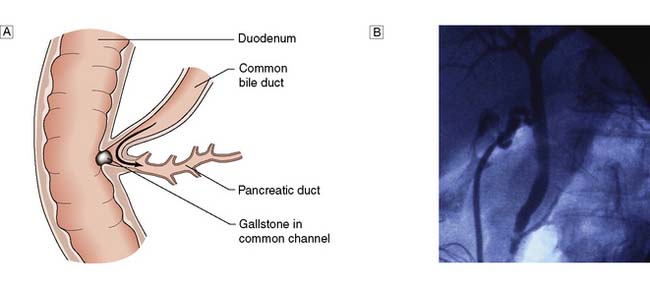

Gallstones are present in some 40% of patients in the UK who develop acute pancreatitis, but tiny gallstones or even microscopic crystals (so called microlithiasis) are thought to account for the majority of ‘idiopathic’ cases. Transient impaction of a gallstone within the common channel between the common bile duct and pancreatic duct causes obstruction of the pancreatic duct (Fig. 15.3) and a sequence of events within the pancreatic acinar cells resulting in intracellular activation of pancreatic enzymes, acinar cell damage and pancreatic inflammation.

Diagnosis

Radiology

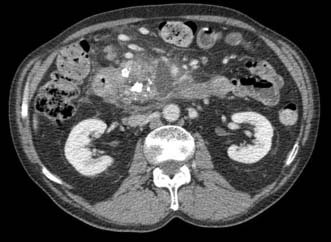

Initial diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is based on clinical features combined with serum amylase levels. The role of radiology in initial assessment is confined to cases where there remains diagnostic doubt, as when serum amylase is non-diagnostic or where the clinical history or examination findings are atypical (for example when there is evidence of generalized peritonitis). In these cases urgent contrast-enhanced CT is mandatory. In patients with acute pancreatitis, changes will be identified ranging from mild peripancreatic oedema through to extensive pancreatic necrosis (Fig. 15.4) but more importantly at this stage, other diagnoses which require urgent operative intervention, such as mesenteric ischaemia or perforated viscus, will be excluded.

Management

Conservative treatment

• Pain relief. Severe pain requires the administration of opiates; there is no evidence to support the use of pethidine rather than morphine.

• Fluid resuscitation. Patients with severe acute pancreatitis often require large volumes of fluid to maintain adequate urine output and blood pressure. Adequate early resuscitation in such cases is the most important consideration in early management and where systemic organ dysfunction is present will necessitate invasive monitoring of venous and arterial pressure. Patients with MODS or SIRS will need oxygen therapy and continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation as well as urine output.

• Suppression of pancreatic function. There is no evidence that suppression of pancreatic function improves the outcome in acute pancreatitis. Nasogastric tubes are not routinely used. Fluids and diet are withheld until nausea and vomiting settle and in cases where systemic complications or other factors prevent recommencement of normal diet, nasoenteric feeding is commenced at an early stage. Suppression of pancreatic secretion by drugs such as octreotide or somatostatin is of no benefit in acute pancreatitis.

• Prevention of infection. Antibiotic prophylaxis has been advocated by some as a means of reducing the risk of infected pancreatic necrosis. Others have been concerned that the more widespread use of antibiotics will result in an increased incidence of severe fungal infection. The most recent consensus is that there is no evidence that prophylactic antibiotics reduce the incidence of infected pancreatic necrosis or mortality (EBM 15.1). It is important to recognize that patients with severe acute pancreatitis often have evidence of SIRS and the presence of a fever and raised white cell count are to be expected, even in the absence of infection. The only definite indication for early antibiotic therapy is when patients are suspected of having cholangitis, which may co-exist with gallstone pancreatitis. Jaundiced patients with SIRS are therefore managed with appropriate broad spectrum antibiotics while arrangements are made for urgent ERCP as described below.

• Inhibition of inflammatory response. Severe acute pancreatitis is one of many conditions where systemic organ dysfunction is driven by the systemic inflammatory response and there has been much experimental and clinical interest in the role of down-regulation of this response as a potential treatment for acute pancreatitis. The only agent that has been studied in large, prospective clinical trials was the platelet-activating factor (PAF) antagonist, lexipafant. Despite encouraging experimental data and promising results from initial clinical trials, a large international trial, recruiting 1500 patients, showed no difference in mortality.

• Nutritional support. Patients with severe acute pancreatitis who are unable to resume normal diet within 48–72 hours require nutritional support. This is best delivered by an enteral rather than parenteral route as meta-analyses of randomized trials (EBM 15.2) have demonstrated that TPN has a higher rate of complications and mortality. There are also sound experimental reasons to believe that enteral nutrition has additional benefits by potentially reducing the risk of bacterial translocation from the gut. There is no evidence that nasojejunal feeding is better or safer than nasogastric feeding but the nasojejunal route will be required where gastric stasis or outlet obstruction prevent effective nasogastric delivery.

• Other measures. A recent randomized trial assessed the role of probiotic therapy as an adjunct to early enteral feeding in the hope that this might reduce bacterial translocation from the gut more than enteral nutrition alone, thus potentially preventing later septic complications. Unfortunately, probiotic therapy actually increased mortality due to gut ischaemia and should no longer be used in these patients. Other proposed treatments which have been found to be of no benefit in prospective clinical trials include antiprotease therapy and peritoneal lavage.

15.1 Prophylactic antibiotics in severe acute pancreatitis

Bai Y, Gao J, Zou DW, Li ZS. Prophylactic antibiotics cannot reduce infected pancreatic necrosis and mortality in acute necrotizing pancreatitis: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103(1):104–110.

Endoscopic treatment

Gallstone pancreatitis is due to the transient impaction of a stone at the papilla causing pancreatic duct obstruction. There is good experimental evidence that the duration of this obstruction is an important determinant of the severity of an attack and so early removal of an impacted gallstone by ERC and sphincterotomy has long been proposed as a potential treatment option for patients. Unfortunately the results from randomized trials have been conflicting, and differences in study design have made direct comparisons difficult. Patients with evidence of obstructive jaundice and SIRS within the first 24 hours are suffering from or are at least at risk of developing cholangitis and there is broad consensus that these patients should have urgent ERC with sphincterotomy. However the majority of patients will pass the gallstone spontaneously and in this situation ERC carries additional risk and no potential benefit (EBM 15.3). The most recent meta-analysis of randomized trials shows no benefit from early ERC in patients with severe acute pancreatitis where cholangitis is not present. Early ERC with stone removal can however be life-saving in the patient with cholangitis and it is important to be alert to this possibility in patients diagnosed as having severe acute pancreatitis. Our own practice is to perform urgent ERC and sphincterotomy only in patients with acute pancreatitis associated with obstructive jaundice and SIRS but there is considerable variation in practice across the UK.

Surgical treatment

1. Where an alternative diagnosis is suggested by CT following initial assessment.

2. Where gallstones are considered the likely cause, cholecystectomy is carried out after recovery from the acute attack. In patients with mild acute pancreatitis this is best carried out during the index hospital admission but following a severe attack, cholecystectomy is delayed until resolution of the inflammatory process. Even after severe acute pancreatitis it is usually possible to perform cholecystectomy by the laparoscopic route. In patients who have had no prior imaging of the common bile duct by MRCP or ERC, it is important to carry out operative cholangiography to exclude bile duct stones. In patients considered unfit for cholecystectomy, ERC with endoscopic sphincterotomy is carried out to protect against further attacks.

Complications

Infected pancreatic necrosis

Pancreatic pseudocyst

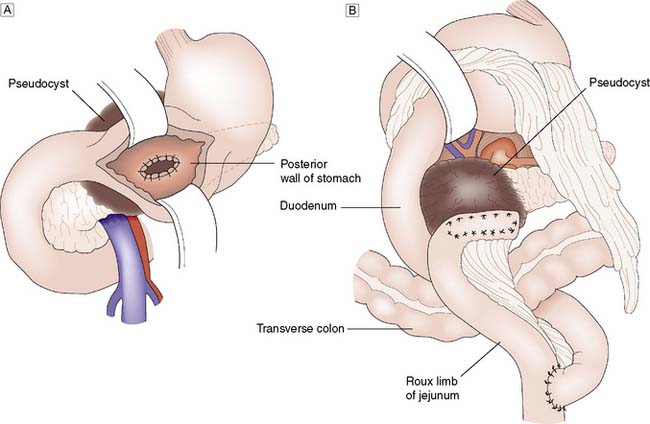

A pancreatic pseudocyst is a collection of pancreatic secretions and inflammatory exudate enclosed in a wall of fibrous or granulation tissue. It differs from a true cyst in that the collection has no epithelial lining and is surrounded by inflammatory tissue. Pseudocysts form most commonly in the lesser sac or in the adjacent retroperitoneum, and by consensus are differentiated from acute fluid collections in that they persist for 4 or more weeks from the onset of acute pancreatitis (Fig. 15.5). Small pseudocysts are usually asymptomatic and resolve spontaneously. In about 10% of patients, larger collections persist and can pose problems.

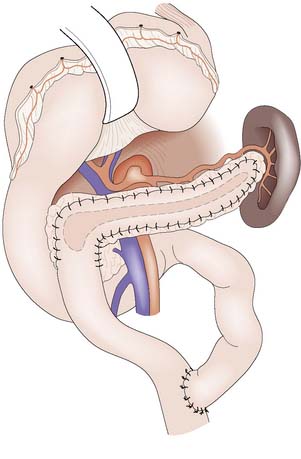

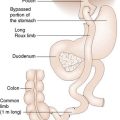

The presence of a pseudocyst is not in itself an indication for surgical treatment. Approximately 50% of asymptomatic pseudocysts will resolve up to 12 weeks following the onset of acute pancreatitis. Treatment is indicated only if the pseudocyst is enlarging or symptomatic, and aims to prevent infection of the contents, haemorrhage or rupture. Simple percutaneous drainage carries a high risk of recurrence and some form of internal drainage is usually preferred. The conventional surgical approach consists of drainage of the pseudocyst into the stomach (pseudocyst-gastrostomy), a Roux loop of jejunum (pseudocyst-jejunostomy), or duodenum (pseudocyst-duodenostomy); whichever appears most appropriate (Fig. 15.6). As the tissues holding the sutures must be firm, it is desirable to avoid surgery until at least 6 weeks after the onset of the acute attack to allow the walls of the pseudocyst to ‘mature’. Endoscopic cyst-gastrostomy or cyst-duodenostomy offers an alternative to surgery, and is now usually carried out under endoscopic ultrasound guidance. Laparoscopic cystgastrostomy or cyst-enterostomy is also described but the relative roles of conventional surgical, laparoscopic and endoscopic drainage have yet to be determined. The selection of the appropriate procedure is often determined by the clinical presentation, anatomical features of the fluid collection, the extent of necrosis present and of course, local expertise. A multidisciplinary approach is mandatory.

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Severe acute pancreatitis may be complicated by bleeding from gastritis, erosions or duodenal ulceration, and prophylactic PPI therapy is advisable. Bleeding which occurs following treatment of infected pancreatic necrosis is usually a consequence of erosion of a retroperitoneal vessel, often the splenic artery or a major branch of this vessel. Control is best achieved by mesenteric angiography with embolization where possible but surgical control may be necessary. Mortality from such bleeding remains high, particularly where surgical intervention is required. In patients with pseudocysts, bleeding may occur into the cyst causing sudden pain and often collapse. This is due to rupture of a false aneurysm within the wall of the pseudocyst and again is best managed by mesenteric embolization where possible. Overt evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding in a patient with infected pancreatic necrosis or pancreatic pseudocyst commonly indicates a communication between the retroperitoneal collections and the lumen of the GI tract (commonly stomach or colon) and urgent mesenteric angiography (or CT angiography if the patient is sufficiently stable) (Fig. 15.7) rather than endoscopy is the appropriate course of action.

Chronic pancreatitis

Investigations and diagnosis

The initial investigation for suspected chronic pancreatitis is CT. This may reveal the speckled calcification typical of chronic pancreatitis or may show evidence of inflammatory changes or pancreatic duct dilatation or pseudocyst formation (Fig. 15.8). MRCP is of value to reveal the architecture of the pancreatic duct, particularly if surgery or endoscopic therapy is contemplated. When investigating these patients, it must be borne in mind that cancer of the pancreas may block the duct system and cause pancreatitis, and that the two conditions can co-exist. Endoscopic ultrasound is increasingly utilized where diagnostic uncertainty exists, allowing pancreatic fine needle biopsy where appropriate.

Surgical treatment

In general, the objective is to relieve pain or compression, while at the same time conserving as much healthy pancreatic tissue and function as possible. Surgery involves drainage of the obstructed pancreatic duct into a Roux loop of jejunum, usually combined with some form of duodenum preserving pancreatic head resection. The two most commonly performed procedures are those described by Beger and Frey (Fig. 15.9), the difference between them being the greater extent of pancreatic parenchymal excision and need for formal division of the pancreatic neck in the Beger procedure. No one procedure has been proven to be superior. Approximately 70% of patients remain pain-free or substantially improved when assessed 5 years after surgery for chronic pancreatitis. As with all aspects of chronic pancreatitis treatment, the results of surgery are better in patients who manage to abstain from alcohol.

Neoplasms of the exocrine pancreas

Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas

Pathology

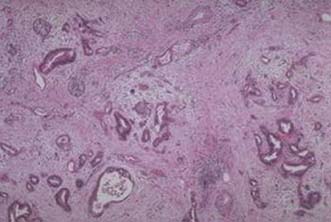

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)

The majority of adenocarcinomas arise from ductal rather than acinar tissue, 60% arising in the head of the gland. The histology (Fig. 15.10) is characterized by groups of infiltrating carcinoma cells often some (histological) distance apart, interspersed by a fibrous stroma, with involvement of nerves, vessels, lymphatics and lymph nodes, at a relatively early phase. Metastatic spread is most commonly to the liver and lung; 80% of patients present with either locoregional or metastatic dissemination.

Mucinous cystic neoplasm

Mucinous cystic tumours of the pancreas predominate in the body and tail of the pancreas and have a strong female predilection. They are multiloculated tumours with a characteristic smooth glistening surface, a dense fibrous wall and occasional calcification (Fig. 15.11). They arise from oversecretion of the mucus by the hyperplastic columnar lining of the ducts and therefore contain thickened viscous material, which can also be haemorrhagic. These tumours should be considered potentially malignant but are classified histologically as benign, borderline, or malignant based on degree of dysplastic changes.

Solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas

Solid pseudopapillary tumour, otherwise known as solid-cystic tumour, or Frantz tumour of the pancreas, is an unusual form of pancreatic carcinoma (Fig. 15.12). Its natural history differs from the more common pancreatic adenocarcinoma in that it is almost always in female patients (10:1), often at a young age (20–30 years), is more indolent, and carries a better prognosis. Pathologically, the tumour is usually well circumscribed with regions of necrosis, haemorrhage, and cystic degeneration. Metastatic disease can occur, usually involving the liver, and resection is the preferred treatment.

Clinical features of pancreatic neoplasms

Presenting symptoms are dependent on the site of the tumour within the pancreas. For tumours in the head of the pancreas, painless jaundice, associated with weight loss is the classical presentation. Involvement of the common bile duct as it runs through the head of the pancreas, results in a block to the flow of bile from the liver to the intestine, resulting in obstructive jaundice where the urine is dark and the interruption of the enterohepatic circulation results in pale stools due to the lack of bile pigments The gallbladder may become dilated and palpable (although non-tender) and this is a worrying sign in a jaundiced patient (Courvoisier’s Law; Table 15.2). Intense itching may result in skin excoriation from scratching. Loss of taste, poor appetite and weight loss are common.

| Courvoisier’s Law | Trousseau’s Sign |

|---|---|

| In the presence of a non-tender palpable gallbladder, painless jaundice is unlikely to be caused by gallstones | Thrombophlebitis migrans in a patient with pancreatic carcinoma, a non-metastatic manifestation of malignancy |

For tumours of the body and tail, biliary obstruction occurs late, and symptoms are often vague, with anorexia, weight loss and with subsequent involvement of the retroperitoneum, the development of back pain. New onset diabetes may predate the diagnosis. Delay in diagnosis is common, although increasing numbers are being diagnosed through cross sectional imaging studies. Steatorrhoea may result in initial investigations for an alteration in bowel habit. A late manifestation is a malignancy-associated hypercoagulable state, resulting in intravascular clots with vasculitis, named thrombophlebitis migrans (Trousseau’s sign, Table 15.2).

Investigations and multidisciplinary management (MDM) planning

High quality multidetector CT scanning (Fig. 15.13), ± MR/MRCP can noninvasively define the site of the lesion and the extent of local or distant involvement. Diagnostic endoscopy may allow biopsy of an ampullary lesion. Endoscopic ultrasound can provide information on local staging, and also provide cytological confirmation of the diagnosis (EUS-FNA) without compromising resectability. Circulating tumour markers (e.g. CA 19–9) lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis but may be useful in the follow-up of treated patients.

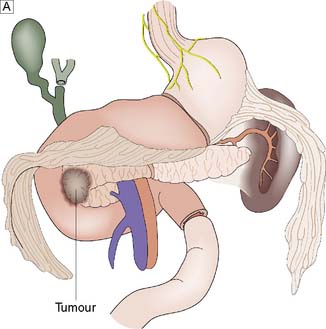

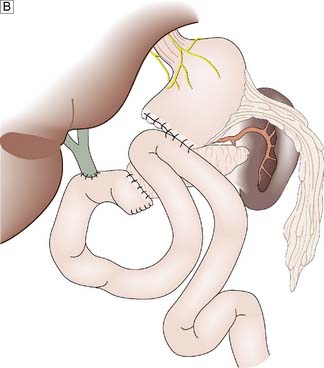

Curative management

For tumours sited in the head of the pancreas the standard operation is a pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple’s procedure) (Fig. 15.14), which entails block resection of the head of the pancreas, the distal half of the stomach, the duodenum, gallbladder and common bile duct. Reconstruction is achieved by anastomoses of the pancreatic tail remnant to the jejunum (or stomach) and anastomosing the common hepatic duct and the stomach to the jejunum. The procedure used to carry a prohibitively high operative mortality, but in specialist hands this should now be less than 5%. Attempts to improve prognosis through escalating the radicality of resection by removing all of the pancreas or by extending the lymphadenectomy have proved disappointing. A standard pancreaticoduodenectomy combined with adjuvant chemotherapy, remains the standard of care, and is associated with a median survival of 24 months, although long-term cure remains a rarity. The prospects for patients with cancer of the periampullary region, distal common bile duct or duodenum are less gloomy, with 5-year survival rates ranging from 20% to 40%.

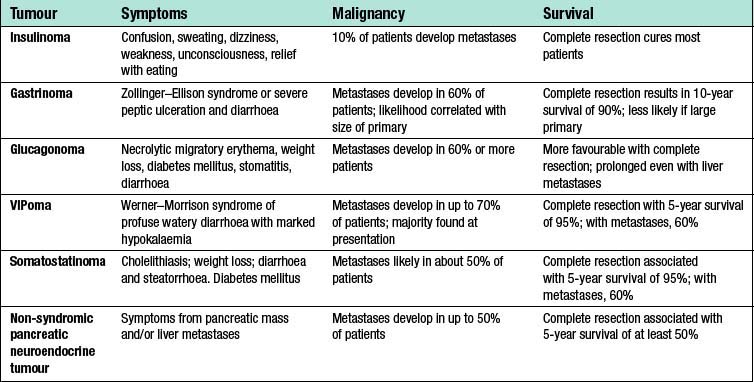

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (PET)

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours are rare tumours (approximately 1/100 000 population/year) of which 60% are non-functioning or secrete peptides with low biological impact such as PP or neurotensin. In contrast to insulinoma, the majority of which are benign, approximately 50% of gastrinomas and the majority of non-functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours are malignant (Table 15.3). They are usually sporadic but they may also appear among other features of genetic syndromes like multiple endocrine neoplasia type I or von Hippel–Lindau disease. In multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN)1, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours occur in 40–80% of patients and are mostly non-functioning tumours or gastrinomas. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours occur in 10–15% of patients with Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) and are frequently multiple (> 30%).

Non-functioning PET

Many non- functional PETs are already metastatic by the time of diagnosis with the liver being the most common site of metastasis. Regional lymph node spread is also common, and PET may have a 5-year survival as low as 30%. Presentation is related to the mass effect of the tumour – symptoms are therefore often non-specific. Surgery with curative intent is the mainstay of treatment for localized or locoregional disease (Fig. 15.15). Non-functioning tumours should also be resected if sporadic and if > 2 cm in MEN1 or > 2–3 cm in VHL. Debulking surgery as well as other forms of local treatment like transarterial chemo-embolization or radiofrequency ablation can improve prognosis, even in patients with liver metastases. Systemic therapies have also been better defined and include radionuclide therapy against somatostatin receptors or MIBG and chemotherapy especially for poorly differentiated tumours. Cytotoxic therapy with compounds like streptozotocin, 5-fluorouracil or doxorubicin can achieve modest outcome.

Miscellaneous PETs

For VIPomas, glucagonomas, somatostatinomas, and PPomas, the biochemical markers are vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), glucagon, somatostatin, and PP, respectively, and the clinical features are detailed in Table 15.3. These tumours are malignant in the vast majority of patients and may present as large tumours at the time of diagnosis. Up to 70% of patients have evidence of spread of the tumour at the time of diagnosis. Aggressive surgical removal of as much tumour as possible is often indicated to relieve some of the severe symptoms that these tumours may cause because of secretion of hormones.

The spleen

Technique of splenectomy

Preoperative preparation

As many of the indications (Table 15.4) are for haematological conditions, preparation requires multidisciplinary management to ensure preoperative optimization of full blood count and coagulation status, and usually involves a further course of steroids or administration of blood products. Vaccines are best administered two weeks before surgery.

| Traumatic | Blunt / penetrating trauma Iatrogenic intraoperative / endoscopic trauma |

| Haematological | The purpuras Haemolytic anaemia Hypersplenism Proliferative disease |

| Miscellaneous | Distal pancreatectomy (for benign or malignant disease) Proximal gastrectomy Splenorenal shunt |

Traumatic splenectomy

In the majority of situations which require an emergency splenectomy for trauma (Table 15.5), the potential for injury is relatively obvious through a history of blunt or penetrating trauma. Delayed presentation, an unusual mechanism (e.g. post-colonoscopy) or the absence of a history through intoxication make a high index of suspicion essential. In addition, in patients with splenic enlargement, the mechanism may be relatively trivial. The cardinal features are those of significant blood loss, and local signs of peritoneal irritation (peritonitis or left shoulder tip pain).

Table 15.5 The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma classification of splenic trauma.

| Grade | Injury | Description |

|---|---|---|

| I | Haematoma | Subcapsular, < 10% of surface area |

| Laceration | Capsular tear < 1 cm parenchymal depth | |

| II | Haematoma | Subcapsular, 10–50% of surface area, Intraparenchymal, < 5 cm in diameter |

| Laceration | 1–3 cm parenchymal depth which does not involve a trabecular vessel | |

| III | Haematoma | Subcapsular, > 50% of surface area, or expanding Ruptured subcapsular or parenchymal haematoma |

| Laceration | Intraparenchymal haematoma > 5 cm or expanding | |

| IV | Laceration | Laceration involving segmental or hilar vessels producing major devascularization (> 25% of spleen) |

| V | Laceration | Massive disruption of pancreatic head |

| Vascular | Hilar vascular injury which devascularizes spleen |