13 The oesophagus, stomach and duodenum

Surgical anatomy

Oesophagus

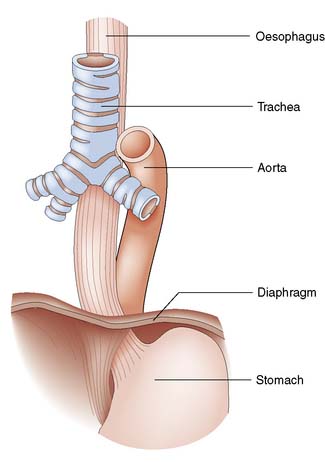

The oesophagus extends from the cricoid cartilage (at the level of vertebra C6) to the gastric cardia and is 25 cm long. It has cervical, thoracic and abdominal portions. The oesophagus passes through the diaphragm at the level of the 10th thoracic vertebra and the final 2–4 cm lie within the peritoneal cavity. The relationships are shown in Figure 13.1.

Stomach and duodenum

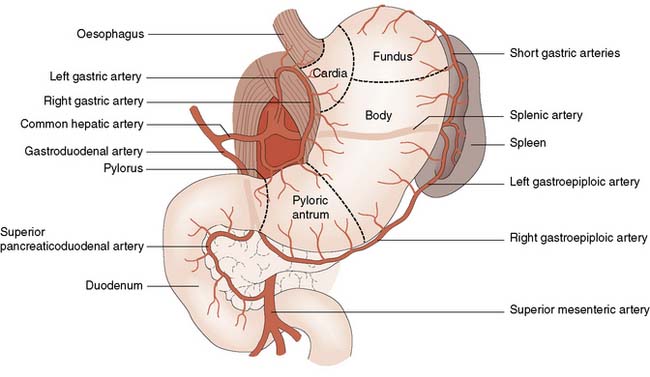

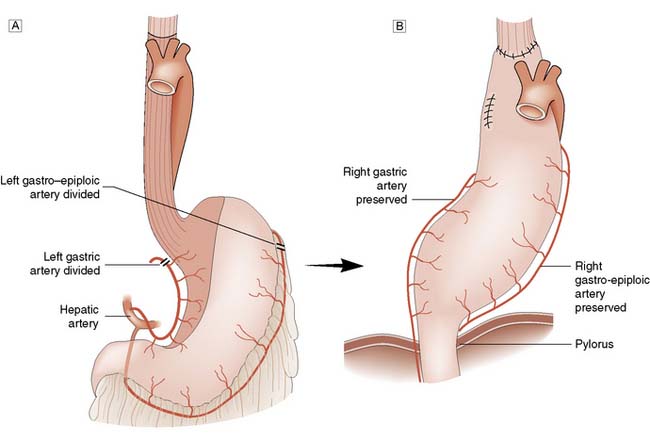

The stomach has an extensive blood supply (Fig. 13.2) derived from the coeliac axis. When the stomach is used as a conduit in the chest, as in an oesophagectomy, the left gastric, left gastroepiploic and short gastric vessels are divided, and the stomach then relies on the right gastric and right gastroepiploic vessels for viability. Ischaemia does not usually result because of the free communication between the vessels supplying the stomach. The blood supply to the duodenum is derived from both the coeliac axis (via the gastroduodenal artery) and branches from the superior mesenteric artery. The veins from the stomach and the duodenum accompany the arteries and drain into the portal venous system.

Surgical physiology

Gastric secretions

Classically, gastric secretion has been divided into three phases:

• Cephalic (neural) phase. Signals arise in the central cortex or appetite centres, triggered by the sight, smell, taste and thought of food, and travel down the vagus nerves to the stomach

• Gastric phase. Food (in particular protein digestion products) causes the release of acid, this release controlled by a negative feedback mechanism dependent upon the pH of the stomach. The gastric phase accounts for the greatest part of daily secretion, approximately 1.5 litres

• Intestinal phase. The presence of food in the duodenum triggers the release of a number of hormones, including duodenal gastrin. These exert a positive feedback effect on the stomach, causing a small increase in gastric secretion.

History and symptoms

Dysphagia

• Onset. Sudden onset suggests a foreign body. In carcinoma, the dysphagia occurs over a period of weeks, whereas in achalasia and benign strictures, symptoms tend to develop over a number of years

• Site. The actual site of obstruction correlates poorly in general to where the patient feels the discomfort, although some patients who feel the obstruction to be high may have a pharyngeal pouch

• Progression. Dysphagia due to an oesophageal stricture (benign or malignant) tends to be progressive whereas patients with motility disorders will often have intermittent symptoms.

• Severity. Difficulty in swallowing solids is initially typical of carcinoma, whereas achalasia and other motility disorders tends to be associated with dysphagia to liquids as well

• Causes. A list of the common causes of dysphagia is shown in Table 13.1.

| Intraluminal | Intramural | Extrinsic |

|---|---|---|

| Pharynx/upper oesophagus | ||

| Foreign body | Pharyngitis/tonsillitis Moniliasis Sideropenic web Corrosives Carcinoma Myasthenia gravis Bulbar palsy |

Thyroid enlargement Pharyngeal pouch |

| Body of oesophagus | ||

| Foreign body | Corrosives Peptic oesophagitis Carcinoma |

Mediastinal lymph nodes Aortic aneurysm |

| Lower oesophagus | ||

| Foreign body | Corrosives Peptic oesophagitis Carcinoma Diffuse oesophageal spasm Systemic sclerosis Achalasia Post-vagotomy |

Para-oesophageal hernia |

Dyspepsia

Dyspepsia is something of a ‘catch all’ term used to describe the symptoms of indigestion. Patients may have some or all of the following; epigastric pain, belching, heartburn, nausea, early satiety or reduced appetite. These symptoms are very common in the general population. Current guidance from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK, recommends lifestyle advice, medication review and empirical treatment for the majority of patients with dyspepsia but without so-called alarm symptoms (weight loss, progressive dysphagia, iron deficiency anaemia, epigastric mass and persistent vomiting) (EBM 13.1). Unfortunately, the symptoms of early upper GI malignancy are very similar to dyspepsia and only advanced malignancies tend to cause alarm symptoms. Patients with advanced upper GI malignancy have a poor prognosis despite aggressive therapy, which creates a dilemma; which patients with dyspepsia should be referred for endoscopy? NICE guidance on dyspepsia should be applied with caution and doctors should have a low threshold for endoscopy in any patient who does not improve quickly with simple treatment. It is also imperative that a careful history is taken and anaemia excluded.

Examination

Physical examination might reveal signs that will aid in the diagnosis of upper GI disorders. A smooth tongue, pallor and koilonychia are signs of iron deficiency anaemia, which can be present in oesophageal carcinoma, oesophagitis and Plummer–Vinson syndrome (see p. 176).

Investigations

Chest X-ray

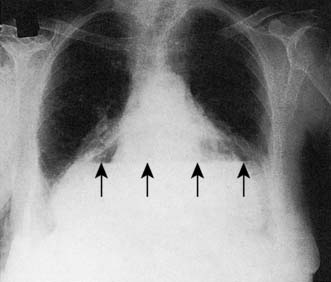

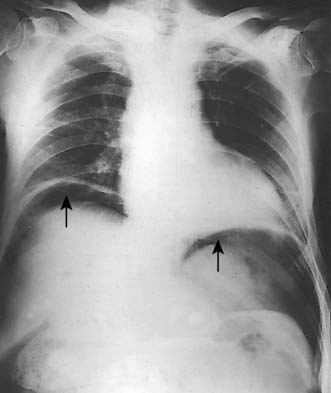

A simple chest X-ray may show any of the following signs: pulmonary consolidation and fibrosis following aspiration in patients with oesophageal motility disorders and oesophageal carcinoma, an air-fluid level behind the heart shadow from a large hiatus hernia with intrathoracic stomach (Fig. 13.3), a mediastinal mass of lymph nodes and pulmonary metastases in oesophagogastric cancer, air in the mediastinum and neck after perforation of the oesophagus (Fig. 13.4) or under the diaphragm from a perforated peptic ulcer (Fig.13.5).

Contrast swallow/meal

A contrast swallow/meal using barium liquid or water soluble contrast may be useful:

• As a primary investigation when access to endoscopy is limited (Fig. 13.6)

• In a very frail patient with dysphagia or vomiting who might not be deemed fit enough for endoscopy (rare)

• To exclude a pharyngeal pouch prior to endoscopy

• To complement endoscopy and provide additional anatomical information (i.e. for patients with a large hiatus hernia) (Fig. 13.7)

Endoluminal ultrasound

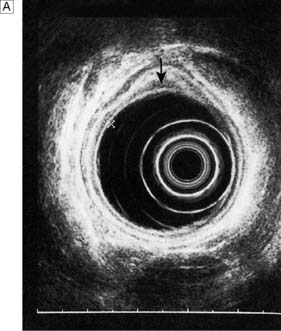

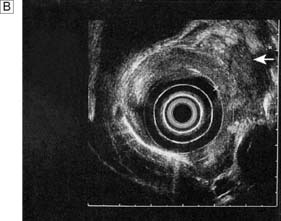

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) uses a variety of endoscopes containing high frequency ultrasound probes at their tips to investigate patients with upper GI disorders. By placing the probe within the GI lumen great detail of the underlying structures can be obtained. EUS is mostly used for staging the ‘T’ and ‘N’ component of TNM staging for oesophagogastric cancer (Fig. 13.8). In addition, EUS is increasingly being used to allow fine needle biopsy of suspicious lymph nodes, especially when the status (positive or negative for cancer) will have profound implications for the intention of a patient’s treatment (curative or palliative). EUS is also useful for investigating submucosal lesions of the stomach such as gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) (Fig. 13.9) (see p. 176).

Manometry and pH studies

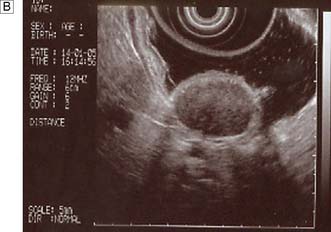

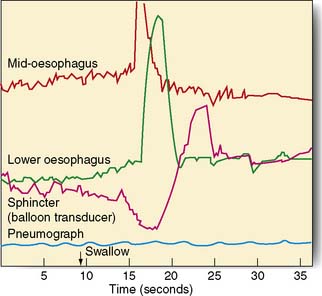

Measurements of lower oesophageal pH can be made over a 24-hour period using an intraluminal electrode placed 5 cm proximal to the lower oesophageal sphincter attached to a catheter passed through the nose and pharynx. Alternatively, oesophageal pH can be measured over three days using a Bravo capsule® which is clipped to the oesophageal mucosa and is wireless (Fig. 13.10). Patients can indicate symptom events during the recording and these can be correlated with the pH trace. A composite scoring system (the DeMeester score) is then used to diagnose pathological GORD. Oesophageal pressure and peristalsis can also be analysed during a series of swallows (station manometry) or over a longer period (ambulatory manometry) (Fig. 13.11). To diagnose gastro-oesophageal bile reflux in patients with duodenogastric reflux a Bilitec probe® is used.

Diagnosis and management – oesophagus

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and Barrett’s oesophagus

• a physiological high-pressure zone (not a true sphincter) in the lower end of the oesophagus

• the mucosal rosette at the cardia, which acts like a plug

• the angle at which the oesophagus joins the stomach between the left border of the oesophagus and the fundus (angle of His)

• the diaphragmatic sling (crura), which acts like a pinchcock at the lower end of the oesophagus

• the high-pressure area at the lower end of the oesophagus, caused by the positive intra-abdominal pressure.

Diagnosis and management

Barrett’s oesophagus is a histological diagnosis made after endoscopic biopsies. GORD can cause oesophagitis and in some patients this leads to a metaplastic change in the mucosa from squamous to columnar type. Barrett’s oesophagus is of interest as it can become dysplastic which in turn can lead to oesophageal adenocarcinoma. This disease is increasing in incidence and Barrett’s patients offer a target group for surveillance to detect early neoplastic disease (EBM 13.2).

Anti-reflux surgery

Although surgical treatment of patients with severe anti-reflux disease has always been associated with good long-term outcomes, it has taken the introduction and refinements of laparoscopic techniques to bring the surgical option to more patients. The indications for surgery include those whose symptoms cannot be controlled by medical therapy, those with recurrent strictures despite treatment, and young patients who do not wish to continue taking acid suppression therapy for several decades. Symptoms that fail to be brought under control with acid suppression therapy are usually due to high-volume alkaline reflux, and surgery is an extremely effective cure (EBM 13.3). The presence of Barrett’s metaplasia alone is not considered a suitable indication for anti-reflux surgery.

13.3 Surgery for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

For further information: www.acg.gi.org/physicians/guidelines/GERDTreatment.pdf.

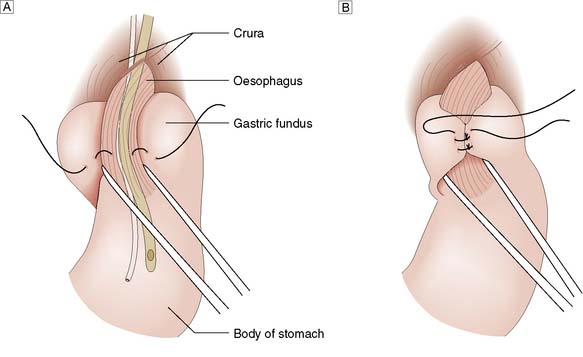

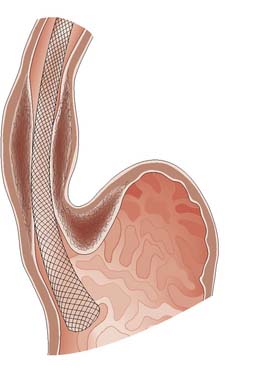

Surgery involves reduction of the hiatus hernia if present, approximation of the crura around the lower oesophagus, and some form of fundoplication. This takes the form of mobilizing the fundus of the stomach from its attachments to the undersurface of the left hemidiaphragm and the left crus, and then wrapping it around the oesophagus, either anteriorly or posteriorly. The most common procedure currently performed is the Nissen fundoplication, in which the fundus is taken posteriorly around the lower oesophagus and sutured to the left anterior surface of the left side of the proximal stomach as a 360° wrap (Fig. 13.12). Other procedures involving a partial (incomplete) fundoplication include the Toupet (posterior 270° wrap) and the Watson (anterior 180° wrap) repairs. Current data do not demonstrate much difference between the various approaches although early postoperative dysphagia is commoner with 360° wraps compared to the partial wraps. All procedures have a success rate in curing the symptoms of reflux of around 90% at a year and 70–80% at 10 years. Unwanted complications after surgery include gas bloat (inability to belch), dysphagia, early satiety and increased flatus. These operations are now carried out laparoscopically, with excellent results in skilled hands.

Fig. 13.12 Fundoplication for GORD.

A Gastric fundus wrapped around the lower oesophagus.B Fundal wrap sutured in position.

Summary Box 13.1 Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

• Reflux type symptoms are very common

• ‘Life style’ advice to patients is important (i.e. smoking, dieting etc)

• Proton pump inhibitors are generally effective treatment

• GORD for > 10 years (especially men) is a risk factor for Barrett’s oesophagus

• Screening and surveillance for Barrett’s patients increasingly relevant

• Laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery is clinically effective and cost efficient.

Hiatus hernia

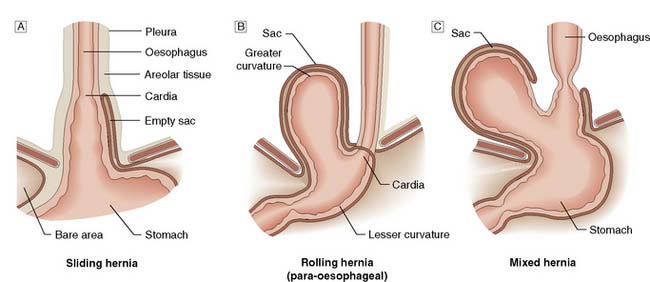

A hiatus hernia is an abnormal protrusion of the stomach through the oesophageal diaphragmatic hiatus into the thorax. There are two types, sliding (90%) and rolling (10%) (Fig. 13.13). A sliding hernia occurs when the stomach slides through the diaphragmatic hiatus, so that the gastro-oesophageal junction lies within the chest cavity. It is covered anteriorly by peritoneum, and posteriorly is extraperitoneal. A rolling or para-oesophageal hernia is formed when the stomach rolls up anteriorly through the hiatus; the cardia remains in its normal position and therefore the cardio-oesophageal sphincter remains intact.

Fig. 13.13 Types of hiatus hernia.

A Sliding hernia.B Rolling hernia (para-oesophageal).C Mixed hernia.

Clinical features

Hiatus hernias are often asymptomatic, but can produce some of or all the following symptoms:

• Heartburn and regurgitation owing to an incompetent lower oesophageal sphincter, which is aggravated by stooping and lying flat at night, and can be relieved by antacids.

• Oesophagitis resulting from persistent acid reflux, which leads to ulceration, bleeding with anaemia, fibrosis and stricture formation.

• Epigastric and lower chest pain, especially in para-oesophageal hernias, as the herniated part of the stomach (usually the fundus) becomes trapped in the hiatus. This can be a surgical emergency owing to the obstruction and strangulation of the stomach.

• Palpitations and hiccups, symptoms caused by the mass effect of the hernia in the thoracic cavity irritating the pericardium and the diaphragm. In patients with a large rolling hiatus hernia, displacement of the whole stomach may result in a volvulus into the chest, producing symptoms of vomiting from gastric outflow obstruction.

Perforation

Aetiology

Outside the wall

These are caused by penetrating injuries such as knife wounds to the neck but are rare.

Investigations

CT scan and contrast swallow

The diagnosis is confirmed by a chest CT scan or water-soluble contrast swallow, which will also demonstrate whether the perforation is localized to the mediastinum or open to the pleural or peritoneal cavities (Fig. 13.14). If oesophageal perforation cannot be excluded after radiological imaging and clinical suspicion remains high an experienced endoscopist should perform an OGD. One potential catch is spontaneous pneumomediastinum which can occur in young adults and teenagers after violent vomiting or coughing and is thought to be due to the rupture of a pulmonary bullous. There is no oesophageal injury and the treatment is conservative.

Tumours of the oesophagus

Carcinoma of the oesophagus

Surgical resection

There are several methods currently used to resect the oesophagus:

• Ivor Lewis two-phase oesophagectomy. This involves a laparotomy during which the stomach is fully mobilized on its vascular pedicles, along with the lower oesophagus. A right thoracotomy is then carried out to resect the oesophagus, and the mobilized stomach is brought up into the chest and anastomosed to the proximal oesophagus. This is the preferred choice for middle and lower-third tumours (Fig. 13.15)

• Left thoracolaparotomy. This is a good approach for tumours around the oesophagogastric junction, particularly when the tumour extends down into the proximal stomach and a more extensive gastric resection is required

• Transhiatal oesophagectomy. This approach involves mobilization of the stomach via an abdominal incision, the oesophagus (some of it by blunt dissection) through the hiatus, and the cervical oesophagus via a left sided neck incision. Once the oesophagus is removed, the stomach is brought up into the neck and anastomosed to the cervical oesophagus. This technique is best suited for very early tumours not requiring a radical lymphadenectomy but is rapidly being replaced by minimally invasive surgery

• Minimally invasive oesophagectomy. Increasingly surgeons are using laparoscopic and thoracoscopic techniques to mobilize the oesophagus. The commonest technique is to mobilize the stomach laparoscopically and then perform a thoracotomy to resect the oesophagus and perform an anastomosis, a so called ‘hybrid technique’. Alternatively both the abdominal and chest phase of the surgery can be done using minimally invasive techniques.

Postoperative care

Uncomplicated recovery after oesophagectomy hinges on good surgical technique, good pain relief (often by epidural analgesia), the avoidance of excess intravenous fluid, early mobilization and effective chest physiotherapy. Many surgeons place a feeding jejunostomy at the time of oesophagectomy to allow early enteral feeding. The early recognition of postoperative complications and their aggressive management has done much to reduce the perioperative mortality of this major operation to around 5% (EBM 13.4).

13.4 Oesophagogastric cancer report

‘The 30-day postoperative mortality rate for oesophagectomy and gastrectomy was 3.8 per cent (95 per cent CI 3.1 to 4.7) and 4.5 per cent (95 per cent CI 3.4 to 5.7), respectively. National oesophagogastric cancer audit report for England & Wales 2010. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/Services/NCASP/audits%20and%20reports/NHS%20IC%20OGC%20Audit%202010%20interactive.pdf

Palliation

Endoscopic stent: Patients with significant dysphagia who are not candidates for radical therapy should be considered for a palliative stent as this is a safe and effective method of relieving the distress of not being able to swallow (Fig. 13.16). They are inserted under intravenous sedation endoscopically but can also be screened into position by interventional radiologists. Chest pain for the first few days after insertion is common and patients should be started on a proton pump inhibitor to reduce reflux symptoms. Complications include perforation during insertion, migration of the stent, blockage and tumour ingrowth. The latter can be rectified by laser ablation or placement of a second stent. Stents cannot be used for very proximal tumours involving the cervical oesophagus.

Fig. 13.16 Self-expanding metal stent inserted to relieve dysphagia from an incurable oesophageal tumour.

Diagnosis and management – gastroduodenal

Peptic ulceration

Pathology

Duodenal ulcers usually occur in the first part of the duodenum and 50% occur on the anterior wall. The majority of gastric ulcers develop on the lesser curvature in the distal half of the stomach. They may co-exist with duodenal ulcers in 10% of patients. Duodenal ulcers may be acute (Fig. 13.17) or chronic. Ulcers with a history of less than 3 months’ duration and with no evidence of fibrosis are considered to be acute. Gastric ulcers generally run a chronic course.

Management of uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease

Medical management

Eradication of H. pylori

Duodenal ulcers

Eradication of the H. pylori has become the mainstay of management in patients with a duodenal ulcer (EBM 13.5). Eradication therapies comprise an antisecretory agent, typically a PPI, together with one or more antibiotics. This ‘triple therapy’ is usually given for 7 days followed by a healing dose of PPI for 4–6 weeks. Eradication rates of greater than 90% occur with good compliance, although reinfection following successful eradication is possible. Without eradication therapy, approximately 80% of ulcers will recur within 1 year. Complete resolution of symptoms is a good indicator of successful eradication. However, where symptoms persist, it is advisable to recheck the H. pylori status.

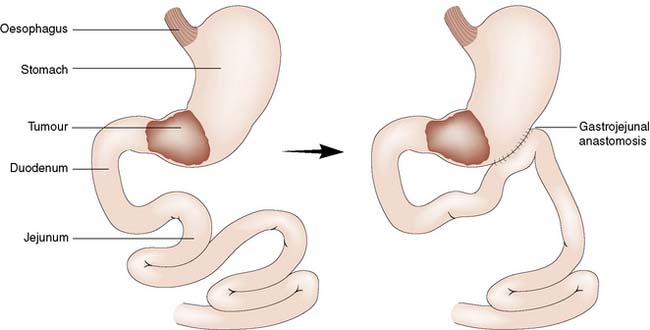

Surgical management

Gastric ulceration

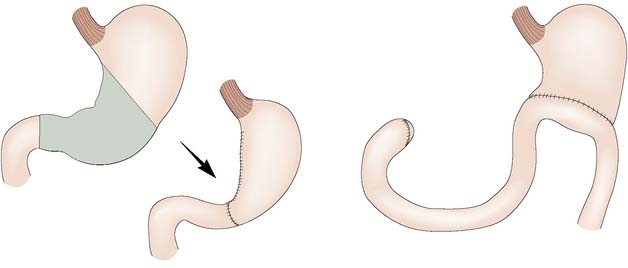

Failure of conservative therapy to heal a gastric ulcer is an indication for surgical intervention. Where malignancy cannot be excluded or is suspected, resection of the ulcer is the treatment of choice. The extent and type of resection will be determined by the position of the ulcer within the stomach and its suspected malignant potential. Benign distal ulcers may be treated by a Billroth I gastrectomy, whereby the distal part of the stomach is removed and the proximal stump anastomosed to the duodenum. More proximal ulcers usually necessitate a Polya-type reconstruction involving anastomosis of the gastric remnant to the jejunum (Fig. 13.18).

Complications of peptic ulceration requiring operative intervention

Perforation

Diagnosis

In 60% of cases of perforation, an erect chest X-ray will demonstrate free air under the diaphragm, although the absence of free air does not exclude a perforation (see Fig. 13.5). A lateral decubitus film can be useful where an erect chest X-ray is not feasible, e.g. because of shock or disability.

Management

Duodenal ulcers

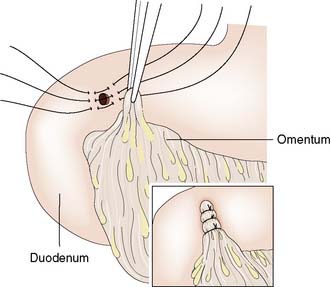

Surgery usually involves simple closure, whereby the ulcer is under-run with sutures or plugged using an omental patch (Fig. 13.19), coupled with a thorough peritoneal lavage. All patients should receive 72 hours of intravenous PPI therapy and then H. pylori eradication therapy and a healing course of oral PPIs.

Gastric ulcers

Summary Box 13.3 Peptic ulcer disease

• Helicobacter pylori is the most important cause – eradicate it

• NSAID medication next commonest cause

• Surgery now only for complications (bleeding and perforation)

• Always biopsy a gastric ulcer – some will be malignant

• If an ulcer fails to heal with medical therapy look for rare causes (i.e. ZE).

Acute haemorrhage

The differential diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal bleeding is summarized in Table 13.2. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding presents with haematemesis (vomiting blood) and/or melaena (the passage of black tarry stool that has a very characteristic smell). Melaena results from the digestion of blood by enzymes and bacteria. Less commonly, melaena may be the result of a bleed from the right colon. Very rarely, if bleeding is very brisk, upper gastrointestinal bleeding may present as fresh rectal bleeding, in which case signs of cardiovascular instability are present. Slow chronic blood loss may be asymptomatic and detected on rectal examination by a positive faecal occult blood test.

Detection and endoscopic treatment

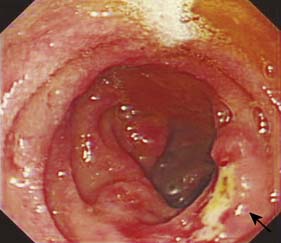

The aims of management of bleeding peptic ulcers are to identify the bleeding point, arrest the bleeding (bleeding ceases spontaneously in 90% of patients) and prevent recurrence. Once resuscitation has occurred, endoscopy is used to detect the site of bleeding (Fig. 13.20), doing so in 80–90% of cases. The endoscopist should also have the necessary experience and training to attempt control of the bleeding using techniques such as adrenaline (epinephrine) 1:10 000 injection and application of heater probes and clips. Bleeding from the ulcer base, the presence of a visible vessel and adherent clot overlying the ulcer are features associated with a significantly increased risk of further bleeding.

Surgical management

• Duodenal ulcers. A bleeding duodenal ulcer may simply be under-run with sutures, through a duodenotomy (opening of the anterior wall of the duodenum) to gain access to the ulcer. Once tolerating oral fluids, the patient should be started on H. pylori eradication therapy empirically.

• Gastric ulcers. With a bleeding gastric ulcer, the possibility of malignancy must be considered. The ulcer must be biopsied in all cases to determine its nature. In young fit patients, the ulcer should be excised completely by taking a small wedge resection. In elderly patients or those with significant co-morbidity, under-running of the ulcer may be preferable, at least in the first instance. If the pathology result confirms malignancy, then the patient should have accurate staging and further treatment as indicated. If the ulcer proves to be benign, H. pylori eradication is indicated. NSAIDs should be avoided.

Gastric neoplasia

Benign gastric neoplasms

Benign tumours of the stomach may arise from epithelial or mesenchymal tissue. Adenomatous polyps may be single or multiple and are the most common benign epithelial neoplasm. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) arise from the pacemaker cells in the gastric wall and have a variable natural history. Diagnosis is usually by endoscopy and EUS; biopsies are rarely helpful as the lesions are submucosal. Small asymptomatic GISTs (up to 2 cm diameter) can safely be left alone but larger ones should be either kept under surveillance (2–5 cm) or resected (> 5 cm). Symptomatic gastric GISTs (bleeding, pain, obstruction) should usually be resected (Fig. 13.21) and laparoscopic techniques are often possible.

Malignant gastric neoplasms

Gastric carcinoma

Aetiology

• Diet. Gastric cancer is noted more commonly where malnutrition is prevalent. It has also been associated with the use of certain preservatives in food; nitrates, nitrites and nitrosamines have been implicated. Where soils are rich in nitrates or dietary intake is high, gastric carcinoma is more common. A high vitamin intake is thought to be protective against the development of cancer of the stomach. Diets rich in carotene and vitamins C and E have been shown to reduce the incidence of intestinal metaplasia in the stomach, a condition thought to be associated with malignant change.

• H. pylori infection. Recent epidemiological studies have suggested that H. pylori may be associated with an increased incidence of malignant change within the stomach (EBM 13.6). At the present time, it is thought that its ability to produce ammonia as well as other mutagenic chemicals may play a part in neoplastic transformation of the gastric mucosa. Such changes are thought to be enhanced by lack of vitamin C.

• Gastric polyps. Hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps are the most frequently found, but only the latter have significant malignant potential. Studies have shown that over one-quarter of adenomatous polyps may show malignant changes within them. Furthermore, gastric carcinoma is frequently encountered in stomachs affected by polyps. This suggests that conditions necessary for the development of polyps may also enhance the development of malignancy.

• Gastroenterostomy. Where there has been a previous gastric resection or duodenal bypass for benign disease and the remaining stomach has been anastomosed to the bile-containing upper gastrointestinal tract, the stomach remnant is more vulnerable to malignant change than the intact stomach. The risk of malignant change increases with the time elapsed since surgery. Patients who have had gastric resections with gastroenterostomy may be 4–5 times more liable to develop gastric carcinoma in the stomach remnant than the normal population.

• Chronic atrophic gastritis. This condition is associated with a loss of the gastric glands from the stomach mucosa. It has been noted to be more frequent in patients at increased risk of developing stomach cancer. Chronic atrophic gastritis is associated with pernicious anaemia, which is linked to an increased risk of gastric cancer. Such patients have a four-fold increased risk compared to the normal population.

• Intestinal metaplasia. This condition arises when the gastric mucosa is replaced by mucosa containing glands that have features more in common with those found in the small intestine. Such changes are usually found in the distal part of the stomach and are associated with an increased risk of development of gastric carcinoma.

• Gastric dysplasia. When the gastric mucosal cells become less uniform in size, shape and organization, dysplastic changes may result and may be low- or high-grade. Patients with high-grade dysplasia often have associated malignant change.

• Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: Inherited mutations of the E-cadherin gene can result in an aggressive form of signet ring gastric adenocarcinoma affecting young patients. Once symptomatic these patients are rarely curable. Consequently, patients with a strong family history of gastric cancer should be referred for genetic counselling and, if appropriate, offered endoscopic surveillance and/or a prophylactic total gastrectomy (EBM 13.7).

13.6 The role of H. pylori eradication in the prevention of gastric cancer

Ley C, et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004;13:4–10. Wong BC, et al. JAMA 2004; 291:187–194.

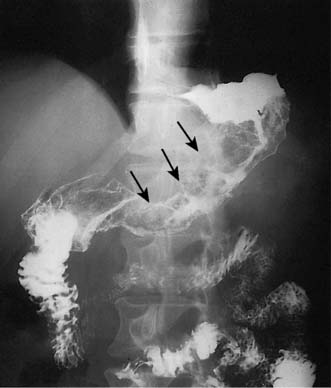

Advanced gastric cancer

The vast majority of malignant gastric tumours found in Western countries are locally advanced gastric adenocarcinomas. These tumours have invaded into the muscularis propria and sometimes through to the serosa. The risk of peritoneal metastases and lympho-vascular invasion is much higher than for early tumours. Advanced gastric tumours often invade the adjacent gastric wall via submucosal lymphatics creating a diffusely thickened and rigid stomach (linitis plastica) (Fig. 13.22). Invasion into adjacent structures such as the pancreas can also occur (Fig. 13.23).

Factors affecting survival in advanced gastric cancer

The survival of patients with advanced gastric cancer depends upon the stage of the tumour at presentation and on the general fitness of the patient. Treatment with curative intent implies surgical resection, increasingly combined with perioperative chemotherapy. For surgery to be curative, excision of the primary tumour must be adequate, with margins clear of the tumour and with satisfactory en bloc resection of all possible involved lymph nodes (EBM 13.8).

13.8 D1 versus D2 (radical) lymph node dissection in gastric cancer

McCulloch P, et al. Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews 2004; CD001964.

A comprehensive pathological classification of tumours has enabled the prognosis of a particular stage of cancer to be estimated. Such staging is usually classified according to the tumour size (T), the node status (N), and the presence or absence of distant metastases (M) (Table 13.3).

| T (Tumour) | |

| T1 | Tumour invades lamina propria or submucosa |

| T2 | Tumour invades muscularis propria or subserosa |

| T3 | Tumour invades serosa |

| T4 | Tumour invades adjacent structures |

| N (Node) | |

| N0 | No lymph node involvement |

| N1 | Fewer than 7 lymph nodes involved by tumour |

| N2 | 7–15 lymph nodes involved by tumour |

| N3 | More than 15 lymph nodes involved by tumour |

| M (Metastases) | |

| M0 | No metastases |

| M1 | Metastases present |

* Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al, eds. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6th edn. Springer-Verlag: New York; 2002.

Staging of gastric carcinoma

• CT: Any patient with a histological diagnosis of gastric cancer should undergo a CT scan of their chest, abdomen and pelvis unless they are very frail. This should provide information about the M-stage (liver, lung, peritoneum and distant nodes) and can help exclude T4 involvement of adjacent structures such as the pancreas.

• EUS: EUS is excellent at determining T-stage. High frequency probes (10 MHz or more) can accurately differentiate between T1–4 disease and add information of local nodal status (N-Stage).

• Staging laparoscopy: This procedure is essential in patients with locally advanced tumours to detect small volume peritoneal and liver metastases that cannot be detected by CT (Fig. 13.24). Peritoneal washings are also helpful as patients with positive peritoneal cytology for malignancy have a very poor prognosis and rarely benefit from surgery.

• PET-CT: Gastric adenocarcinomas are not always PET-avid. This limits PET’s application as a routine staging procedure looking for metastatic disease.

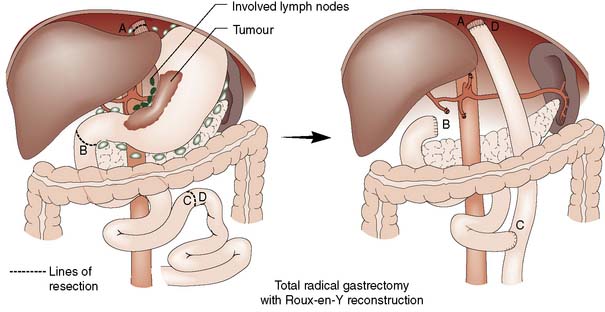

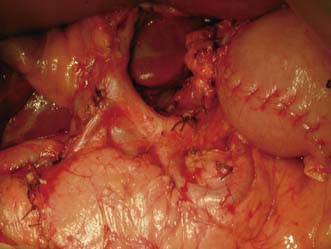

Treatment with curative intent

• Surgery alone: Patient with early gastric cancer should undergo a distal (subtotal) or total D2 gastrectomy (depending upon the site of the tumour) done by an experienced surgeon working in a high volume cancer centre. The ‘D2’ description refers to the excision of both the first tier of perigastric lymph nodes and the second tier of nodes along the gastric arteries (Fig. 13.25). Reconstruction of the gastrointestinal tract is usually by Roux en-Y to prevent bile reflux (Fig. 13.26). When oncologically safe to do so, a distal gastrectomy is preferable to a total gastrectomy as it gives a better quality of life

• Combined therapy: Randomized clinical trials in the UK have shown improved survival for patients who have perioperative chemotherapy and surgery compared to those who have surgery alone. The effect seems most pronounced for advanced tumours; the neo-adjuvant or preoperative component of the chemotherapy seems to have the biggest impact on survival (EBM 13.9). Further trials continue to discover if newer agents such as Bevacizamab can improve survival further. The surgery is the same regardless of whether chemotherapy is given or not.

Fig. 13.25 Operative view of the coeliac axis after D2 nodal dissection and removal of all lymph nodes.

Palliation

• Best supportive care: Some patients are too frail for any anticancer therapy and all focus should be on relieving their symptoms and supporting them and their families through their terminal illness. Nausea and vomiting is treated with antiemetics such as cyclizine or ondansetron. Poor appetite may respond to steroids such as dexamethasone. Pain often requires opiate analgesia. Eating can be particularly difficult for patients with advanced gastric cancer and dietetic support is essential. Towards the end of a patient’s life they may need medication via a subcutaneous infusion from a portable syringe driver.

• Palliative chemotherapy: For patients who are fit enough, valuable improvements in quality of life can be achieved with palliative chemotherapy using combinations of drugs such as epirubicin, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil. In addition, life expectancy can be extended if the tumour is chemosensitive (EBM 13.10).

• Palliative radiotherapy: Bleeding from advanced gastric tumours can be troublesome and can be greatly reduced by a short course of external beam radiation.

• Stenting: Patients with gastric outlet obstruction who have persistent vomiting may benefit from the endoscopic placement of a self-expanding metallic stent although the results are unpredictable.

• Palliative surgery: Options include a gastric bypass (often done laparoscopically) for distal tumours, or a palliative resection. The latter is a big undertaking for patients with incurable disease and should only be considered in those with distal tumours who have not benefitted from lesser interventions and who are fit (Fig. 13.27).

Prognosis

When the tumour is confined to the mucosa or submucosa without lymph node or distant metastases, a 5-year survival of the order of 95–100% can be achieved. With increasing penetration of the tumour through the stomach wall and increasing numbers of nodes involved, the 5-year survival decreases. A further deterioration occurs when distant metastases are present, in which case 5-year survival is unusual (Table 13.4).

Table 13.4 Examples of stages of gastric cancer and their prognosis.

| Stage | 5-year survival (%) |

|---|---|

| T1N0M0 | 95+ |

| T1N1M0 | 70–80 |

| T2N1M0 | 45–50 |

| T3N2M0 | 15–25 |

| M1 | 0–10 |

Other gastric tumours

Carcinoid tumours

Summary Box 13.4 Gastric cancer

Miscellaneous conditions of the duodenum

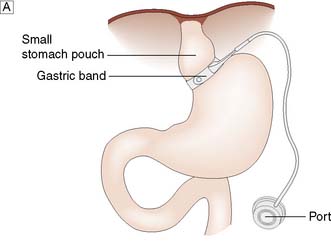

Surgery for obesity

• Restrictive: decreases food intake, as the patient suffers early satiety even after small meals. Overeating causes upper abdominal pain, and vomiting may be required to relieve it

• Malabsorptive: alters digestion, leading to food intake being poorly absorbed and eliminated in the stool. Overeating typically leads to excessive diarrhoea and flatulence.

Operations for obesity

The gastric band is a ring with an inflatable inner cuff, which is placed laparoscopically a short distance below the oesophagogastric junction, creating a small (approximately 50 ml) gastric pouch (Fig. 13.28A). The cuff can be inflated or deflated via injections into a port site located in the subcutaneous tissues, in order to tighten or relax the cuff around the stomach. The tighter the cuff, the longer foodstuffs entering the gastric pouch will take to exit through the ring into the remainder of the stomach and intestinal tract, prolonging the feeling of satiety.

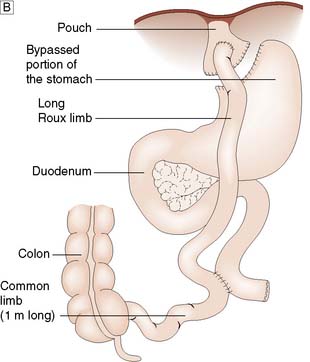

Gastric bypass involves stapling the stomach closed a short distance below the oesophagogastric junction (Fig. 13.28B). A Roux limb is then brought up and anastomosed to the small proximal gastric remnant. Depending on the size of the pouch and calibre of the anastomosis, there will be a degree of restrictive activity, as well as a major malabsorptive element, as food will enter the distal jejunum and proximal ileum without exposure to bile or pancreatic and other digestive enzymes.