Chapter 7 The Neck

A. Neck Features And Swellings

(1) Generalities

The neck is an important crossroad of anatomic structures and organ systems, the most important of which is the thyroid (discussed in Chapter 8).

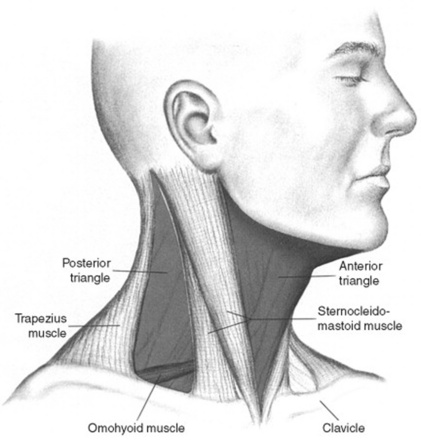

7 What are the anterior and posterior triangles of the neck?

They are important regions of the lateral neck, separated from each other by the sternocleidomastoid muscles (SCMs) (Fig. 7-1). These can be easily located through inspection and palpation, especially if tensed against resistance. The remaining borders of the posterior triangle are the anterior margin of the trapezius and the upper margin of the clavicle, whereas the remaining borders of the anterior triangle are the mandible and midline.

8 What are the contents of the cervical triangles?

In the anterior triangle, one can often palpate the jugulodigastric node. Other nodes are instead undetectable, unless enlarged by infection, inflammation, or malignancy. The anterior triangles also may harbor important embryologic remnants, such as thyroglossal duct/cysts, branchial cysts, and dermoids.

In the anterior triangle, one can often palpate the jugulodigastric node. Other nodes are instead undetectable, unless enlarged by infection, inflammation, or malignancy. The anterior triangles also may harbor important embryologic remnants, such as thyroglossal duct/cysts, branchial cysts, and dermoids.

In the posterior triangle, there are many undetectable nodes that can become enlarged after a pharyngitis or a viral upper respiratory illness (URI).

In the posterior triangle, there are many undetectable nodes that can become enlarged after a pharyngitis or a viral upper respiratory illness (URI).

The subclavian artery may be felt pulsating at the base of the neck, just above the clavicle.

The subclavian artery may be felt pulsating at the base of the neck, just above the clavicle.

The transverse process of the atlas may be palpated high in the neck, between the mandibular angle and mastoid process. It may be misinterpreted as a cervical mass.

The transverse process of the atlas may be palpated high in the neck, between the mandibular angle and mastoid process. It may be misinterpreted as a cervical mass.

The pulsatile common carotid artery (and its prominent bifurcation) is usually felt more laterally, along the SCM.

The pulsatile common carotid artery (and its prominent bifurcation) is usually felt more laterally, along the SCM.

9 Which swellings may be encountered during inspection of the neck?

Many. Classification and origin depend on location (posterior or anterior triangle; and for the latter, midline or lateral aspect) and nature (inflammatory or neoplastic) (Table 7-1).

| Anterior triangle |

| Midline |

Mostly thyroidal—goiter/nodule(s) Mostly thyroidal—goiter/nodule(s) |

Thyroglossal (duct) cyst Thyroglossal (duct) cyst |

Thyroglossal fistula Thyroglossal fistula |

Dermoid (cyst) Dermoid (cyst) |

| Lateral aspect |

Branchial cleft cyst Branchial cleft cyst |

Branchial fistula Branchial fistula |

Branchial hygroma Branchial hygroma |

Cystic hygroma Cystic hygroma |

Laryngocele Laryngocele |

Masseter muscle hypertrophy Masseter muscle hypertrophy |

| Posterior triangle |

| Neoplastic |

Lymphomas Lymphomas |

Metastatic Metastatic |

Neurogenic Neurogenic |

Paragangliomas/glomus tumors Paragangliomas/glomus tumors |

Miscellaneous (ectopic salivary) Miscellaneous (ectopic salivary) |

| Inflammatory: localized |

Tuberculous lymphadenitis (scrofula) Tuberculous lymphadenitis (scrofula) |

Bacterial lymphadenitis (abscess) Bacterial lymphadenitis (abscess) |

Suppurated branchial or thyroglossal cyst Suppurated branchial or thyroglossal cyst |

| Inflammatory: diffuse |

Ludwig’s angina Ludwig’s angina |

(2) Swellings of the Anterior Triangle (Midline)

10 What is the origin of midline swellings of the anterior cervical triangle?

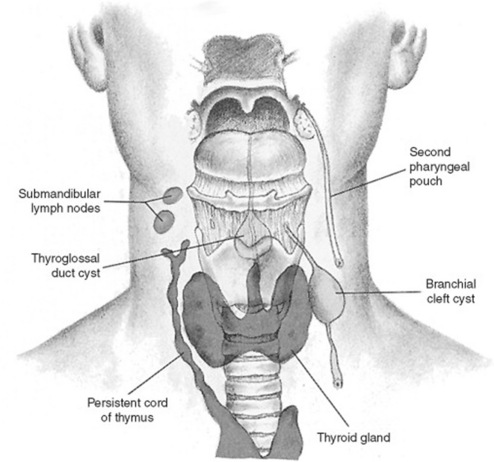

They are mostly thyroidal (goiters or nodules). Less commonly, they represent remnants of embryonic structures, such as dermoids or thyroglossal duct cysts (Fig. 7-2). Since only thyroid and laryngeal structures ascend with deglutition, nonthyroidal masses can be easily identified by asking the patient to swallow.

12 Do thyroglossal cysts transilluminate?

No—which is counterintuitive, considering their cystic nature.

13 How common is a thyroglossal cyst?

Quite common. In fact, of all congenital neck masses, 75% are thyroglossal duct cysts.

14 What accounts for the other 25% of congenital neck masses?

Branchial cleft cysts, typically located more laterally, just between the SCM and hyoid.

21 Is adenopathy common in branchial cysts?

No. If present, consider either tuberculous adenitis (scrofula) or a complicating abscess.

28 How does congenital hypertrophy of the masseter present?

Like a parotid mass. Differentiation can be easily accomplished by palpation.

31 What are the most common neoplastic swellings?

Lymphomas: These commonly present with cervical adenopathy.

Lymphomas: These commonly present with cervical adenopathy.

Metastatic lymphadenitis: Most commonly from thyroid, nasopharynx, and the postcricoid region. Neoplastic nodes may compress or invade the sympathetic chain, thus causing Horner’s syndrome (ptosis and miosis of the affected side).

Metastatic lymphadenitis: Most commonly from thyroid, nasopharynx, and the postcricoid region. Neoplastic nodes may compress or invade the sympathetic chain, thus causing Horner’s syndrome (ptosis and miosis of the affected side).

Neurogenic tumors: These include neurofibromas and neuroblastomas, which, along with lipomas and cystic hygromas, are not uncommon in children.

Neurogenic tumors: These include neurofibromas and neuroblastomas, which, along with lipomas and cystic hygromas, are not uncommon in children.

Paragangliomas or glomus tumors: Rare in the neck—usually at the carotidal bifurcation, or higher up in the parapharyngeal region. May have a pulse and a bruit.

Paragangliomas or glomus tumors: Rare in the neck—usually at the carotidal bifurcation, or higher up in the parapharyngeal region. May have a pulse and a bruit.

Miscellaneous parapharyngeal tumors: Mostly ectopic salivary neoplasms, which, like neurogenic tumors and lymphomas, cause not only neck swelling, but also medial displacement of the pharyngeal wall and tonsil.

Miscellaneous parapharyngeal tumors: Mostly ectopic salivary neoplasms, which, like neurogenic tumors and lymphomas, cause not only neck swelling, but also medial displacement of the pharyngeal wall and tonsil.

39 How does Ludwig’s angina spread?

The submandibular space. This is the primary site of infection in Ludwig’s. It is subdivided into two spaces that communicate posteriorly: (1) the sublingual space, which is bound superiorly by the mouth floor, posteriorly by the tongue base, anterolaterally by the mandible, and inferiorly by the mylohyoid muscle; and (2) the submaxillary space, which is bound superiorly by the mandibular ramus and inferiorly by both the hyoid and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. Note that the anterior and lateral borders of the entire submandibular space are formed by the outer investing fascia’s attachments to the mandible.

The submandibular space. This is the primary site of infection in Ludwig’s. It is subdivided into two spaces that communicate posteriorly: (1) the sublingual space, which is bound superiorly by the mouth floor, posteriorly by the tongue base, anterolaterally by the mandible, and inferiorly by the mylohyoid muscle; and (2) the submaxillary space, which is bound superiorly by the mandibular ramus and inferiorly by both the hyoid and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. Note that the anterior and lateral borders of the entire submandibular space are formed by the outer investing fascia’s attachments to the mandible.

The pharyngomaxillary space. This is bound superiorly by the base of the skull, posteriorly by the prevertebral fascia, laterally by the outer investing fascia, anteriorly by the pterygomandibular raphe, and inferiorly by the hyoid bone. It communicates laterally with the parotid and masticator spaces, and posteriorly with the retropharyngeal space.

The pharyngomaxillary space. This is bound superiorly by the base of the skull, posteriorly by the prevertebral fascia, laterally by the outer investing fascia, anteriorly by the pterygomandibular raphe, and inferiorly by the hyoid bone. It communicates laterally with the parotid and masticator spaces, and posteriorly with the retropharyngeal space.

The retropharyngeal space. This is contained between the middle and deep cervical fascia. It begins superiorly at the base of the skull and extends inferiorly to the upper mediastinum.

The retropharyngeal space. This is contained between the middle and deep cervical fascia. It begins superiorly at the base of the skull and extends inferiorly to the upper mediastinum.

43 What other inflammatory condition may occur in the neck?

An inflamed sebaceous or intradermal cyst. This may occur anywhere, presenting as a smooth subcutaneous mass with a central visible punctum. Its superficial location easily differentiates it from other neck swellings.

An inflamed sebaceous or intradermal cyst. This may occur anywhere, presenting as a smooth subcutaneous mass with a central visible punctum. Its superficial location easily differentiates it from other neck swellings.

Cellulitis. A superficial soft tissue infection different from Ludwig’s—although it also may result from a lower molar dental abscess. Yet there is no localized swelling or masses.

Cellulitis. A superficial soft tissue infection different from Ludwig’s—although it also may result from a lower molar dental abscess. Yet there is no localized swelling or masses.

B. Salivary Glands

47 Where are the sublingual glands?

In the mouth floor, just under the tongue. They are palpable but not routinely assessed.

49 What are the causes of salivary gland swelling?

Bilateral swelling carries a much wider differential diagnosis:

Malnutrition, such as starvation, kwashiorkor, and anorexia nervosa. Painless salivary swelling may occur even in bulimics, who are malnourished but do not look cachectic.

Malnutrition, such as starvation, kwashiorkor, and anorexia nervosa. Painless salivary swelling may occur even in bulimics, who are malnourished but do not look cachectic.

Sjögren’s syndrome. This is a keratoconjunctivitis sicca, characterized by dry eyes (xerophthalmia) and dry mouth (xerostomia). It is caused by a lymphocytic infiltration of salivary and lacrimal glands, associated with an autoimmune arthritis. It was first described in 1933 by Henrik Sjögren, the same surgeon who in 1935 developed corneal transplants.

Sjögren’s syndrome. This is a keratoconjunctivitis sicca, characterized by dry eyes (xerophthalmia) and dry mouth (xerostomia). It is caused by a lymphocytic infiltration of salivary and lacrimal glands, associated with an autoimmune arthritis. It was first described in 1933 by Henrik Sjögren, the same surgeon who in 1935 developed corneal transplants.

Mikulicz’s syndrome. Chronic dacryoadenitis with bilateral painless swelling of lacrimal and salivary glands and decreased-to-absent lacrimation/salivation—not autoimmune but otherwise identical to Sjögren’s. Causes include tuberculosis, Waldenström’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and infiltration by sarcoid and lymphoma. It was first described by Johann von Mikulicz (1850–1905), a pioneering Polish-German surgeon and spare-time pianist, who studied under Billroth, taught at Krakow, and was among the first to use gloves during surgery.

Mikulicz’s syndrome. Chronic dacryoadenitis with bilateral painless swelling of lacrimal and salivary glands and decreased-to-absent lacrimation/salivation—not autoimmune but otherwise identical to Sjögren’s. Causes include tuberculosis, Waldenström’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and infiltration by sarcoid and lymphoma. It was first described by Johann von Mikulicz (1850–1905), a pioneering Polish-German surgeon and spare-time pianist, who studied under Billroth, taught at Krakow, and was among the first to use gloves during surgery.

Alcoholism (with or without cirrhosis). May cause fatty infiltration of the salivary glands and painless enlargement, very much like in the pancreas.

Alcoholism (with or without cirrhosis). May cause fatty infiltration of the salivary glands and painless enlargement, very much like in the pancreas.

Leukemic infiltrates and lymphomas

Leukemic infiltrates and lymphomas

Drugs. Painless (or painful) swelling may result from sulfonamides, propylthiouracil, lead, mercury, and iodide.

Drugs. Painless (or painful) swelling may result from sulfonamides, propylthiouracil, lead, mercury, and iodide.

Acute parotitis. Usually infectious, most commonly viral (mumps). Still, bacterial parotitis also may cause acute swelling and tenderness of the parotids, but this is usually unilateral and limited to debilitated patients with uncontrolled diabetes, renal failure, dehydration, or severe electrolyte imbalances. Often due to staphylococcal infection, it may progress to abscess, causing the overlying skin to become deeply red.

Acute parotitis. Usually infectious, most commonly viral (mumps). Still, bacterial parotitis also may cause acute swelling and tenderness of the parotids, but this is usually unilateral and limited to debilitated patients with uncontrolled diabetes, renal failure, dehydration, or severe electrolyte imbalances. Often due to staphylococcal infection, it may progress to abscess, causing the overlying skin to become deeply red.

C. Trachea

1 Allard RHB. The thyroglossal cyst. Head Neck Surg. 1982;5:134-146.

2 Bailey H. Thyroglossal cysts and fistulae. Br J Surg. 1925;12:579-589.

3 Bounds GA. Subphrenic and mediastinal abscess formation: A complication of Ludwig’s angina. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;23:313-321.

4 Ellis P, Van Nostrand AW. The applied anatomy of thyroglossal tract remnants. Laryngoscope. 1977;87:765-770.

5 Ewing CA, Kornblut A, Greeley C, et al. Presentations of thyroglossal duct cysts in adults. Eur Arch Otorh. 1999;256:136-138.

6 Girard M, Deluca SA. Thyroglossal duct cyst. Am Fam Physician. 1990;42:665-668.

7 Guarisco JL. Congenital head and neck masses in infants and children. Ear Nose Throat J. 1991;70:40-47.

8 Hawkins DB, Jacobsen BE, Klatt EC. Cysts of the thyroglossal duct. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:1254-1258.

9 Himalstein MR. Branchial cysts and fistulas. ENT. 1980;159:2329.

10 Juang YC, Cheng DL, Wang LS, et al. Ludwig’s angina: An analysis of 14 cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 1989;21:121-125.