CHAPTER 360 The Natural History of Cerebral Aneurysms

Natural History of Unruptured Aneurysms

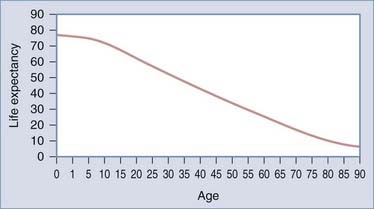

Intact or unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIAs) are aneurysms with no recent or remote history of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Management of these patients is controversial because the natural history from the current studies is unclear.1 The treating physician must evaluate not only the aneurysm but also patient factors such as age, medical condition, and family history. Such information allows the neurosurgeon to make a calculated judgment about the lifetime risk associated with UIAs in comparison to the risk related to treatment. For example, a relatively benign natural history would favor conservative therapy (i.e., observation), particularly in the older population. In contrast, a more malignant natural history in a younger patient would make intervention more urgent. Life tables, which are based on population studies, are an estimate of life expectancy (Fig. 360-1), but an individual may vary considerably from these averages. Therefore, assessment of an individual patient’s risk involves evaluating not only the likelihood of rupture of an intact aneurysm but also the patient’s life expectancy.

Prevalence of Unruptured Aneurysms

There is considerable variation in the reported prevalence of UIAs (Table 360-1). This variation can be attributed to multiple factors, such as the nature of the study (i.e., retrospective or prospective), the mechanism and accuracy of detection (i.e., autopsy, CT, computed tomographic angiography [CTA], MRI, magnetic resonance angiography [MRA], catheter angiography), the interest and focus of the investigator (i.e., pathologist, neuropathologist, or vascular neuropathologist), and definition of a cerebral aneurysm (i.e., 1-mm versus larger expansion at a vessel bifurcation). In addition, the characteristics of the population, such as age (e.g., elderly) and nationality (i.e., Finnish and Japanese), will influence the prevalence. Lifestyle (i.e., tobacco use) and environmental factors (alcohol) may also explain variations in reported prevalence rates of UIAs. Finally, it is becoming more evident that genetic influences are involved in aneurysm formation (for further discussion, please see Chapter 362).

| NO. OF PATIENTS | PREVALENCE | |

|---|---|---|

| Autopsy | ||

| Fox et al., 1983 | 164,764 | 0.8% |

| Radiology | ||

| Pre-CT era: Winn et al., 1978 | 4658 | 0.65% |

| Post-CT era: Ujie et al., 1993 | 1612 | 2.7% |

CT, computed tomography.

Rinkel and colleagues comprehensively reviewed 23 studies including more than 50,000 patients and noted a prevalence, on average, of 0.4% in retrospective autopsy studies, 3.6% in prospective autopsy studies, 3.7% in retrospective angiography studies, and 6.0% in prospective angiography studies.2 As just noted, this variation can be attributed to the nature of the population studied and the mechanisms used to document the presence of a UIA. Most of the angiographic studies analyzed by Rinkel and coworkers originated in the post-CT/MRI era, which may have skewed the prevalence of UIAs upward.2 In the post-CT/MRI era, angiography is used mainly for patients with vascular disease and therefore encompasses an older segment of the patient population. In contrast, a pre-CT (see Table 360-1) study based on angiography revealed a prevalence of 0.65%. In the pre-CT era, angiography was used more liberally; a broader segment of the population was surveyed and therefore may be more representative of the true prevalence of UIAs.

Rupture Rate of Unruptured Aneurysms

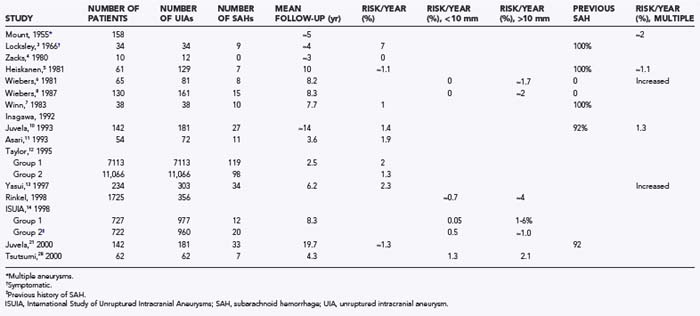

Despite intensive investigations, the incidence of SAH in patients with UIAs is not perfectly defined, as shown in the following studies (summarized in Table 360-2):

The strengths of the ISUIA include its multicenter design, which minimizes referral and treatment bias, and its size, which provides robust statistical power to formulate conclusions.14 The study has, however, been challenged on a number of points that are largely related to selection bias, the retrospective nature of the study, and the inclusion of patients with cavernous aneurysms in the study population.1,15–17 Cavernous carotid aneurysms are known to have a lower risk for hemorrhage.18 However, after excluding intracavernous aneurysms, the investigators concluded that the rate of hemorrhage was only slightly increased from 0.05% to 0.066% per year for small aneurysms and from 0.95% to 1.38% for large aneurysms.19

The most significant criticism of the study is related to the possibility of selection bias. Does the population studied truly represent a population of patients with UIA, or has some selection bias created a population with an inherently lower risk for rupture? This concern is particularly significant because selection bias cannot be corrected with any statistical methods. In regard to selection bias, all patients were selected for observation or surgery after consultation with a neurosurgeon.1,15–17,20 If it is assumed that most experienced neurosurgeons have an intuitive concept of what constitutes an aneurysm at high risk for rupture (e.g., size, configuration, family history), it is reasonable to presume that high-risk patients were treated and removed from the study pool. Removal of these high-risk patients could potentially skew the risk for rupture downward. Indeed, a calculation by Winn and associates based on the low rupture rate in the ISUIA project resulted in an extraordinary high UIA prevalence rate of 16% to 33%.1,20 This calculated prevalence rate derived from ISUIA data is several magnitudes larger than the reported prevalence rates of UIAs2 (see Table 360-1).

As with other studies, the analysis by Juvela and colleagues21 has limitations. Although the study generally lacked selection bias, the aneurysm population was derived from 30 to 50 years ago, before the introduction of imaging techniques, and it may represent a different group of patients than seen today.22 In addition, the data were compiled from a single center with the inherent single-center bias.23 A potential does exists for genetic bias because the Finnish population is known to have a higher prevalence of UIAs, a higher incidence of SAH (13 to 16 per 100,000 persons per year24,25) than in other Western countries (10/100,000 persons per year26), and a different aneurysm distribution (higher frequency of middle cerebral artery aneurysms).17,27 Most importantly, with regard to the validity of the natural history of UIAs, the study had insufficient numbers of truly incidental asymptomatic aneurysms; only 5 (4%) of the 142 patients had no previous history of SAH.21 The patients in the study by Juvela and associates21 were similar to those reported by Winn and coauthors7 in that the study involved long-term follow-up of patients with multiple aneurysm who suffered an SAH and had the offending lesion clipped, as well as similar to the patients in group 2 of the ISUIA study. All three studies reported a rate of rupture approximating 1%.

However, this study by Tsutsumi and colleagues28 must be interpreted with caution because the sample population was small and the power of the statistical analysis is therefore in question. Moreover, the follow-up period was relatively short, and the data were derived from a single center, with the associated single-center bias. The patients were obtained from a population of patients undergoing cerebral angiography who were older (mean age, 70.8 years) and had a high concomitant rate of ischemic and hemorrhagic events.

Factors Associated with Rupture

Aneurysm Size

Aneurysm size has long been considered to be an important independent variable in the risk for rupture. This was first clearly demonstrated in the study by Wiebers and coworkers in 1981, who reported a zero risk of rupture for aneurysms less than 10 mm in diameter versus an approximate 1.7% risk per year for aneurysms larger than 10 mm.6 These findings were supported in their later study reported in 1987.8 Other studies have also supported the relationship between size and rupture rate.2,7,21,28,29

Aneurysm Location

The large ISUIA study found that site was an independent variable in the incidence of SAH: basilar tip, vertebrobasilar, posterior cerebral, and posterior communicating artery aneurysms had a higher risk for rupture. The increased risk for rupture of aneurysms with a basilar artery location was also noted by Wiebers and colleagues in an earlier study.6 Rinkel and associates demonstrated that the relative risk for aneurysm rupture was higher for aneurysms located in the posterior circulation, with a relative risk of 4.1.2

In summary, UIAs located at the basilar bifurcation, and posterior communicating artery locations appear to have a higher risk for rupture than do UIAs at other sites. In contrast, as noted earlier,18 aneurysms within the cavernous sinus appear to have a lower likelihood of bleeding.

Multiple Aneurysms

For example, in 1974 Mount and Brisman reviewed 158 patients with unruptured, multiple aneurysms (which included the earlier study of Heiskanen and Marttila30) monitored for an average of 5 years and noted a bleeding rate of at least 2% per year.30 Wiebers and associates also found that multiple aneurysms had a greater propensity for rupture than did solitary aneurysms.6,8 This was consistent with the data from Winn and colleagues.7 Yasui and coworkers demonstrated an annual rupture rate of 6.8% in patients with multiple aneurysms and 1.9% in those with single UIAs.13 A meta-analysis by Rinkel and associates found that the risk for rupture was higher in patients with multiple aneurysms, with a 1.7 relative risk for rupture in patients with multiple lesions in comparison to those with an asymptomatic lesion.2 In contrast, a study conducted in Helsinki by Juvela and colleagues with 2 decades of follow-up did not confirm a higher risk for SAH in patients with multiple UIAs.10,21

Aneurysm Growth

The report by Juvela and coauthors of patients harboring a UIA had a median follow-up period of 14 years and noted that aneurysms that subsequently ruptured (17 patients) displayed a significant increase in size.10 Among the 14 patients for whom angiographic follow-up was available and in whom there was no sign of rupture, no significant increase in aneurysm size was noted. Interestingly, growth was strongly associated with cigarette smoking (odds ratio [OR], 3.48; 95% CI, 1.14 to 10.64; P < .05).10 In contrast, Sampei and coworkers observed the growth of aneurysms between successive angiographic examinations in 25 patients and noted that rebleeding did not appear to be affected by the growth rate or by the initial size of the aneurysm.31 However, 11 of the patients were monitored for only less than 1 month.

Symptomatic Aneurysms

Symptomatic aneurysms are aneurysms accompanied by signs and symptoms related to the lesion, excluding clinical features related to SAH. The symptoms may be mild, such as headaches, or more severe, such as cranial nerve palsies and brainstem signs. The studies of Locksley3 and Rinkel and colleagues2 support the existence of a relationship between symptomatic UIAs and an increased propensity for rupture. In the Cooperative Aneurysm Study, 34 patients with symptomatic, unruptured aneurysms were observed for almost 4 years (47 months), and 26% died of SAH (≈7%/yr).3 This rate was significantly higher than the rupture rate for incidental aneurysms (0.8%/yr). Rinkel and colleagues found that the relative risk for rupture of a symptomatic aneurysm was 8.2 times that of an asymptomatic lesion.2 However, in a multivariate analysis by Wiebers and associates, no correlation could be found between risk for hemorrhage and symptoms.6 This was also the case for Juvela and coworkers, who found that the percentage of patients without SAH was 65% to 80% at 20 years of follow-up, which did not differ significantly when symptomatic and nonsymptomatic (i.e., incidental) aneurysms were compared.10

Excluding headaches as a symptom, the majority of symptomatic aneurysms are associated with cranial nerve III dysfunction and are therefore most likely located at the posterior communicating location. This location has been found to have a higher rate of rupture of UIAs.14,32–34 Moreover, to affect cranial nerve III function, a UIA must enlarge. Increased size has been demonstrated to be correlated with hemorrhage. Thus, the perception that symptomatic UIAs have an increased rate of rupture may be an epiphenomenon related to aneurysm location and size.

In summary, the data are equivocal on an association between symptoms and rupture in UIAs.

Patient Age

Increasing age has been thought to increase the risk for hemorrhage. Wier, in a comprehensive review of the literature, stated that the rate of aneurysm rupture progressively increases with age but that extreme old age is protective.35 An increased risk for hemorrhage with increasing age was also demonstrated by Wiebers and colleagues, but only in patients whose aneurysm was 10 mm or larger.8 Juvela and coauthors noted that the only variable that tended to predict rupture was the age of the patient.10,21 Age as a predictor of rupture was also demonstrated in the ISUIA,14 but just in patients with a history of SAH (group 2). However, a protective effect of age was suggested in the earlier autopsy data from McCormick,36 as well as in a subsequent large population analysis by Taylor and colleagues of more than 20,000 elderly patients,12 although the shortened life expectancy (see Fig. 360-1) of the moderately to extremely elderly (i.e., reduced duration of risk) may account for the suggestion of age serving as protection against rupture of UIAs.

Systemic Hypertension

The role of hypertension in aneurysm formation and rupture has been controversial. The concept of hypertension increasing the risk for hemorrhage makes intuitive sense. However, Stehbens, in a review of pathology data, concluded that no association exists between hypertension and SAH,37,38 and other studies have arrived at similar conclusions.6,8,10,39 In contrast, though, some investigators have found that hypertension increases the risk for SAH. For example, the study by Sacco and associates, which reviewed the data on 5184 residents of Framingham, Massachusetts, demonstrated a significantly higher risk for SAH in patients with hypertension.23 Winn and colleagues described the long-term (7.7 years) outcome in patients with multiple aneurysms who had suffered an SAH and had their offending lesion directly clipped.7 Systemic hypertension was found to increase the risk for subsequent rupture of a previously intact UIA. Asari and Ohmoto analyzed data from 54 patients with 72 unruptured aneurysms and found that hypertension was significant in predicting future rupture.11

In 1995, Taylor and colleagues described the demographics and prevalence of hypertension in 20,767 Medicare patients with unruptured aneurysms and compared these results with a random sample of the hospitalized Medicare population.12 For patients with an unruptured cerebral aneurysm as the primary diagnosis, hypertension was found to be a significant risk factor for future SAH (risk ratio, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.01 to 2.11). A study by Inagawa found that the frequency of hypertension was increased in patients with UIAs but was not related to risk for rupture.40

Strong support for hypertension being a risk factor comes from the remarkable prospective study by Sandvei and associates from one county in Norway in which 75,000 individuals were monitored for more than 2 decades. The authors found that hypertension was significantly overrepresented in patients subsequently suffering an aneurysmal SAH.41

Cigarette Smoking

Cigarette smoking has been statistically associated with the occurrence of aneurysmal SAH. In a multicenter study, prospective data revealed that patients with SAH reported current smoking rates 2.5 times higher than expected based on U.S. and European national surveys.42 Moreover, cigarette smoking was also associated with younger age at the onset of SAH (5 to 10 years younger, P < .0001).43 Matsumoto and colleagues observed 123 patients with an unruptured cerebral aneurysm incidentally detected during investigation for other diseases.43 Sixty-nine patients, shown to be free of cerebral aneurysms with MRA, served as a control population. Smoking significantly increased the risk for aneurysm formation and SAH, especially in women and younger patients.43 In 2000, Qureshi and associates, in analyzing prospectively collected data from a multicenter clinical trial, found that smoking (OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.1 to 4.5) was independently associated with large aneurysms in patients with SAH. As noted previously, aneurysmal size is associated with risk for rupture of UIAs. The prospective study by Sandvei and colleagues found that past and current smokers had a significantly higher likelihood of having an aneurysmal SAH than nonsmokers did.41

Alcohol, Diabetes Mellitus, and Metabolic Factors

Alcohol use and the presence of diabetes mellitus did not appear to be overly represented in 285 patients with UIA.40 In contrast, alcohol use has been found to be associated with and diabetes to be protective of nonaneurysmal SAH.44 The prospective study by Sandvei and associates revealed that high body mass was protective against aneurysmal SAH.41

Gender

It has long been recognized that cerebral aneurysms occur more frequently in females than in males.36,37,45 With respect to gender and rupture rate, several studies suggest that female gender increases the risk for rupture. For example, the meta-analysis of nine studies by Rinkle and colleagues found a higher rupture rate in women, with a relative risk of 2.1.2 In addition, Juvela and coworkers found that female gender was an independent risk factor for rupture of UIAs.21 However, in the large analysis of hospital data, Taylor and associates found that gender was not a predictor for risk of hemorrhage.12

In summary, women may have an increased likelihood for UIA rupture, but the data are inconclusive.

Genetic and Molecular Factors

A comprehensive discussion of the genetics of cerebral aneurysms is presented in Chapter 362. However, in brief, based on a number of observations,46,47 there is increasing evidence of a genetic role in the formation of cerebral aneurysms. Moreover, genetic and molecular factors may be associated with an increased rate of rupture of UIAs.47–52 For example, several diseases, such autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), Marfan’s disease, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, have been associated with an increased prevalence and rupture of UIAs.53 Unruptured cerebral aneurysms have been found in 6% of patients with ADPKD and no family history of UIAs, a figure higher than in the non-ADPKD population.54 In ADPKD patients with a family history of UIAs, the prevalence has been found to be 16%.54 The latter patients also appear to have an increased risk for rupture of UIAs.54

In similar fashion, patients who have more than one first-degree relative with a cerebral aneurysm have a risk of harboring a UIA as high as 4% to 25%.46,55,56 The percentage of patients with a discernible family history of aneurysmal SAH may be miscalculated by a bedside interview,57 and consequently, previous studies may have underestimated this genetic connection. Familial UIAs appear to rupture sooner, at a smaller size, and be located less frequently at the anterior communicating location.46,58,59 Moreover, familial UIAs occur as multiple rather than single aneurysms. Further evidence of a genetic basis is the concordant presence of UIAs in monozygotic twins60 and the higher rate of aneurysm formation and rupture in the Finnish and Japanese populations.61

Natural History of Ruptured Aneurysms

In contrast to the natural history of UIAs, which is still unclear, the natural history of ruptured aneurysms is better defined and based significantly on randomized trials comparing surgery with bed rest therapy.3,62–69 These trials stem from an era when the results of surgery and conservative therapy for ruptured aneurysms were equivocal.62–64 The results from these various studies defined the natural history of ruptured cerebral aneurysms and are divided into two epochs: short term (hospitalization to 6 months after the initial SAH) and long term (after 6 months). Not to be ignored is the initial epoch or prehospital (or never hospitalized) period. This prehospital phase is frequently overlooked and can be documented only with population-based studies. Three percent to 18% of patients suffering an SAH die before hospitalization.70,71 The variation in prehospital death rate may reflect the setting (urban versus rural), medical retrieval system, geography, rigor in analyzing prehospital deaths, or any combination of these factors. However, variation in the prehospital death rate may indicate the potential for improvement in the treatment of aneurysmal SAH.

Short-Term Outcome: Post-hospitalization Period to Six Months

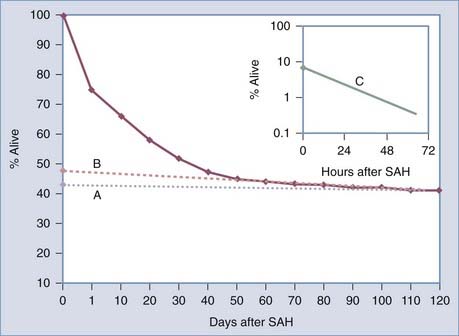

For hospitalized SAH patients, mortality is associated with initial hemorrhage, rebleeding, related complications such as vasospasm and hydrocephalus, and medical complications.70 The initial direct effects are the major cause of mortality, but rebleeding also makes a significant contribution.70 Locksley provided another view of the natural history in his analysis of the survival of 830 conservatively treated patients after rupture of a single aneurysm (Fig. 360-2).3 Three populations were identified by curve-stripping technique: group 1 (9% of the population) had a half-life that was measured in hours. This segment of the SAH population represents grade V patients.72 The second group (47% of the population) had a half-life measured in days. These patients are probably representative of grade III patients. The last group, 43% of the population, had a half-life measured in months and represents patients with the best grade.

Factors Associated with Outcome after Aneurysm Rupture

Grade on Admission

As illustrated in Table 360-3, there is a strong statistical correlation between clinical grade on admission and mortality during the first 6 months after the initial hemorrhage.34 This association was subsequently confirmed in a study by Philips and coworkers39 and more recently by Lagares and colleagues.73

TABLE 360-3 Hunt and Hess Grade on Admission Is Strongly Correlated (P < .001) with Mortality at 6 Months in Conservatively Managed Patients (N = 364)

| GRADE | MORTALITY (%) |

|---|---|

| I | 15 |

| II | 30 |

| III | 50 |

| IV | 65 |

| V | 95 |

(From Winn HR, Richardson AE, Jane JA. The long-term prognosis in untreated cerebral aneurysms: I. The incidence of late hemorrhage in cerebral aneurysm: a 10-year evaluation of 364 patients. Ann Neurol. 1977;1:358-370.).

Aneurysm Location

In addition to clinical grade on admission, aneurysm location is also associated with mortality as indicated in Table 360-4.34 Thus, mortality at 6 months in conservatively treated patients was 34% to 39% after rupture of an anterior circulation aneurysm, approached 50% in patients with multiple aneurysms, and was a higher still (61%) with aneurysms arising from the posterior circulation.34

| ANEURYSM LOCATION | MORTALITY (%) |

|---|---|

| ACA | 33.7 |

| PCA | 36.6 |

| MCA | 39.3 |

| Multiple | 47.0 |

| VBA | 60.9 |

ACA, anterior communicating artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; PCA, posterior communicating artery; VBA, vertebral-basilar arteries.

* The original population consisted of 719 patients with a single ruptured aneurysm.

Time after Hemorrhage

Time after hemorrhage is also correlated with mortality.74 For patients seen immediately after their aneurysm ruptures, the likelihood of 1-month survival is approximately 40%. In contrast, if a patient is not seen for 24 hours, the likelihood of survival to 1 month is “improved” to 60%. Alternatively, if a patient does not come to medical attention for 7 days, the likelihood of survival to 1 month is almost 80%. The difference in survival is related to the high mortality during the initial period after SAH (see Fig. 360-2). The association between time after hemorrhage and survival is important to consider when evaluating individual patients, as well as when reviewing the results of treatment studies in the literature.

Molecular and Genetic Profiles

A variety of molecular factors have been investigated to determine whether their presence is associated with outcome. Leung and associates recently tested the hypothesis that the apolipoprotein E genotype (APOE4) would be expressed more frequently in patients with an unfavorable outcome. Apolipoprotein E is a known “injury factor.”75 In 72 patients, APOE4 was detected in 15 (21%). These investigators found that age and clinical and CT grade were associated with outcome in univariate analysis, as was the presence of APOE4. In multiple logistic regression analysis, the association with APOE4 persisted (OR, 11.3; 95% CI, 2.2 to 57.0; P = .003), although the gain in discrimination was small. Other molecular markers have also been studied, and it is anticipated that in the future, this aspect of SAH will be intensively expanded.47

Environmental Factors

Pobereskin found smoking to be positively associated with survival after aneurysmal SAH.76

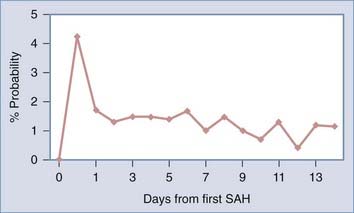

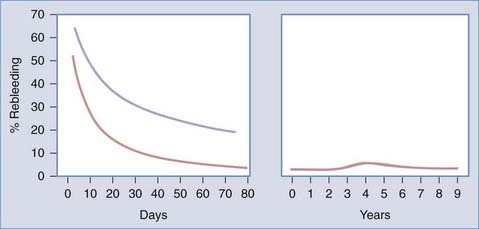

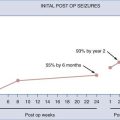

Rebleeding

Rebleeding is strongly correlated with mortality.32–34 The rate of rebleeding is highest during the first 24 hours,32–3477 as indicated in Figure 360-3, and may be particularly high during the first 6 hours.78 The probability of rebleeding on a daily basis is higher than 4% on the first day, decreases in subsequent days to 1% to 2%, and exhibits a slow decline extending out to 6 months. Factors related to rebleeding are discussed later.

Gender

The influence of gender on outcome after aneurysmal SAH is unclear. Most studies, including population-based analyses, have not identified any difference in mortality in men versus women70 but did note a difference in mortality in premenopausal versus postmenopausal women.79

Factors Associated with Rebleeding

A variety of aneurysm and patient factors have been found to be associated with rebleeding in the early phase (hospitalization to 6 months). For example, Hunt-Hess clinical grade on admission (OR, 1.92 per grade; 95% CI, 1.33 to 2.75; P < .001) and maximum aneurysm diameter (OR, 1.07/mm; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.13; P = .005) were independent predictors of rebleeding.80 Other factors associated with rebleeding have been noted to differ, depending on aneurysm location (see Table 360-4). For example, the risk of rebleeding from anterior communicating aneurysms is increased by the following factors: gender (females), aneurysms that point superiorly and have a wide neck, history of coma, systemic hypertension, and elderly age. The associated risk factors for bleeding from posterior communicating aneurysms are different and include age, larger aneurysms, the presence of clot, and vasospasm. More recently, configuration of the aneurysm sac and intra-aneurysm blood flow dynamics as determined by microanalysis have been implicated in rebleeding.81–83 Finally, recent studies suggest that molecular and genetics factors may be influencing rebleeding rates.84,85

Late Follow-up: after Six Months

The cooperative aneurysm trial in 1966,65–68 as well as the earlier prescient aneurysm trial at Atkinson Morley’s Hospital in Wimbledon, England, under the direction of McKissock and Richardson,32,33,62–64,86–88 relegated in a random fashion a large number of patients to bed rest. These individuals were then subsequently observed over the course of many years, which allowed the long-term natural history of conservatively treated patients to be defined. Before analyzing these data, the long-term outcome, as measured in years, was thought to be benign,65,89 with the development of “healed” aneurysms and no or minimal risk of rehemorrhage.

Late Rebleeding

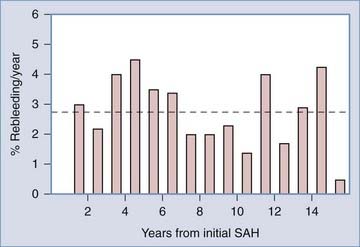

Long-term studies have revealed that aneurysms do not “heal.” Instead, long-term follow-up has documented a persistent yearly rebleeding rate of approximately 3% and persistence of this rate well into the second decade of follow-up.71,90 As illustrated in Figure 360-4, the average rebleeding rate over the initial 15 years of observation was 2.74% per year. The rate of rebleeding during the acute period as measured in days is in contrast to the rate of rebleeding as measured in years in Figure 360-5.

Late Mortality

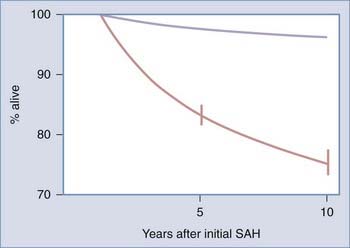

The overall mortality associated with a late hemorrhage approximated 60%. The mortality rate of 60% is similar to that observed during the acute period (0 to 6 months) when the prehospital deaths are included. It is interesting that 18% of the patient who rebled late died before they could be hospitalized. Over the course of decades of follow-up, the majority of deaths were related to fatal rebleeding, which occurred at a yearly rate of 2% to 3%. Even when late SAH deaths were excluded, these patients had a higher mortality rate than age-matched patients did (Fig. 360-6). The primary cause of non–SAH-associated deaths was cardiovascular disease.

Alvord ECJr, Loeser JD, Bailey WL, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage due to ruptured aneurysms. A simple method of estimating prognosis. Arch Neurol. 1972;27:273-284.

Bromberg JE, Rinkel GJ, Algra A, et al. Subarachnoid haemorrhage in first and second degree relatives of patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:288-289.

Graf CJ. Prognosis for patients with nonsurgically-treated aneurysms. Analysis of the Cooperative Study of Intracranial Aneurysms and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1971;35:438-443.

Heiskanen O. Risk of bleeding from unruptured aneurysm in cases with multiple intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1981;55:524-526.

Inagawa T. Risk factors for the formation and rupture of intracranial saccular aneurysms in Shimane, Japan. World Neurosurg. 2010:155-164.

Juvela S, Porras M, Poussa K. Natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: probability of and risk factors for aneurysm rupture. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:379-387.

Kassell NF, Torner JC. Aneurysmal rebleeding: a preliminary report from the Cooperative Aneurysm Study. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:479-481.

Locksley HB. Natural history of subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracranial aneurysms and arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:321-368.

McKissock W, Richardson A, Walsh L. Posterior-communicating aneurysms: a controlled trial of the conservative and surgical treatment of ruptured aneurysms of the internal carotid artery at or near the point of origin of the posterior communicating artery. Lancet. 1960;1:1203-1206.

McKissock W, Richardson A, Walsh L, et al. Multiple intracranial aneurysms. Lancet. 1964;1:623-626.

McKissock W, Walsh L. Subarachnoid haemorrhage due to intracranial aneurysms; results of treatment of 249 verified cases. Br Med J. 1956;2:559-565.

McKissock W, Richardson A, Walsh L. Anterior communicating aneurysms: a trial of conservative and surgical treatment. Lancet. 1965;1:874-876.

McKissock W, Richardson AE, Walsh L. Middle-cerebral aneurysms. Further results in the controlled trial of conservative and surgical treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Lancet. 1962;2:417-420.

Mount LA, Brisman R. Treatment of multiple aneurysms—symptomatic and asymptomatic. Clin Neurosurg. 1974;21:166-170.

Nishioka H. Report on the Cooperative Study of Intracranial Aneurysms and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Section VII. I. Evaluation of the conservative management of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:574-592.

Nishioka H. Results of the treatment of intracranial aneurysms by occlusion of the carotid artery in the neck. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:660-704.

Perret G, Nishioka H. Report on the Cooperative Study of Intracranial Aneurysms and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. IV. Cerebral angiography. An analysis of the diagnostic value and complications of carotid and vertebral angiography in 5,484 patients. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:98-114.

Perret G, Nishioka H. Report on the cooperative Study of Intracranial Aneurysms and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Section VI. Arteriovenous malformations. An analysis of 545 cases of cranio-cerebral arteriovenous malformations and fistulae reported to the cooperative study. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:467-490.

Pirson Y, Chauveau D, Torres V. Management of cerebral aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:269-276.

Richardson AE, Jane JA, Payne PM. Assessment of the natural history of anterior communicating aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1964;21:266-274.

Richardson AE, Jane JA, Payne PM. The prediction of morbidity and mortality in anterior communicating aneurysms treated by proximal anterior cerebral ligation. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:280-283.

Richardson AE, Jane JA, Yashon D. Prognostic factors in the untreated course of posterior communicating aneurysms. Arch Neurol. 1966;14:172-176.

Rinkel GJ, Djibuti M, Algra A, et al. Prevalence and risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review. Stroke. 1998;29:251-256.

Rinne J, Hernesniemi J, Niskanen M, et al. Analysis of 561 patients with 690 middle cerebral artery aneurysms: anatomic and clinical features as correlated to management outcome. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:2-11.

Sahs AL, Perret G, Locksley HB, et al. Preliminary remarks on subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1966;24:782-788.

Sandvei MS, Romundstad PR, Muller TB, et al. Risk factors for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in a prospective population study: the HUNT study in Norway. Stroke. 2009;40:1958-1962.

Stehbens WE. Pathology of the Cerebral Blood Vessels. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1972.

Taylor CL, Yuan Z, Selman WR, et al. Cerebral arterial aneurysm formation and rupture in 20,767 elderly patients: hypertension and other risk factors. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:812-819.

Tsutsumi K, Ueki K, Morita A, et al. Risk of rupture from incidental cerebral aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:550-553.

Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Sundt TMJr, et al. The significance of unruptured intracranial saccular aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:23-29.

Winn HR, Almaani WS, Berga SL, et al. The long-term outcome in patients with multiple aneurysms. Incidence of late hemorrhage and implications for treatment of incidental aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:642-651.

Winn HR, Jane JASr, Taylor J, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic incidental aneurysms: review of 4568 arteriograms. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:43-49.

Winn HR, Richardson AE, Jane JA. The long-term prognosis in untreated cerebral aneurysms: I. The incidence of late hemorrhage in cerebral aneurysm: a 10-year evaluation of 364 patients. Ann Neurol. 1977;1:358-370.

Winn HR, Richardson AE, Jane J, editors. The Assessment of the Natural History of Single Aneurysms That Have Ruptured. New York: Raven Press. 1982:1-10.

Winn HR, Richardson AE, O’Brien W, et al. The long-term prognosis in untreated cerebral aneurysms: II. Late morbidity and mortality. Ann Neurol. 1978;4:418-426.

Zacks DJ, Russell DB, Miller JD. Fortuitously discovered intracranial aneurysms. Arch Neurol. 1980;37:39-41.

1 Winn H. Section overview: unruptured aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:1-2.

2 Rinkel GJ, Djibuti M, Algra A, et al. Prevalence and risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review. Stroke. 1998;29:251-256.

3 Locksley HB. Natural history of subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracranial aneurysms and arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:321-368.

4 Zacks DJ, Russell DB, Miller JD. Fortuitously discovered intracranial aneurysms. Arch Neurol. 1980;37:39-41.

5 Heiskanen O. Risk of bleeding from unruptured aneurysm in cases with multiple intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1981;55:524-526.

6 Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, O’Fallon WM. The natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:696-698.

7 Winn HR, Almaani WS, Berga SL, et al. The long-term outcome in patients with multiple aneurysms. Incidence of late hemorrhage and implications for treatment of incidental aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:642-651.

8 Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Sundt TMJr, et al. The significance of unruptured intracranial saccular aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:23-29.

9 Easton J, Castel J, Wiebers D. Management of unruptured aneurysms. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1993;3:60-64.

10 Juvela S, Porras M, Heiskanen O. Natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a long-term follow-up study. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:174-182.

11 Asari S, Ohmoto T. Natural history and risk factors of unruptured cerebral aneurysms. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1993;95:205-214.

12 Taylor CL, Yuan Z, Selman WR, et al. Cerebral arterial aneurysm formation and rupture in 20,767 elderly patients: hypertension and other risk factors. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:812-819.

13 Yasui N, Suzuki A, Nishimura H, et al. Long-term follow-up study of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:1155-1159.

14 Unruptured intracranial aneurysms—risk of rupture and risks of surgical intervention. International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1725-1733.

15 Piepgras DG. Unruptured aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:63.

16 Juvela S. Unruptured aneurysms [editorial]. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:58-60.

17 Dumont AS, Lanzino G, Kassell NF. Unruptured aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:52-56.

18 Inagawa T, Hada H, Katoh Y. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms in elderly patients. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:364-370.

19 Piepgras D, Kassell N, Torner J. A response from the ISUIA. Surg Neurol. 1999;52:428-429.

20 Winn HR, Jane JASr, Taylor J, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic incidental aneurysms: review of 4568 arteriograms. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:43-49.

21 Juvela S, Porras M, Poussa K. Natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: probability of and risk factors for aneurysm rupture. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:379-387.

22 Wiebers DO, Piepgras DG, Brown RDJr, et al. Unruptured aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:50-51.

23 Sacco RL, Wolf PA, Bharucha NE, et al. Subarachnoid and intracerebral hemorrhage: natural history, prognosis, and precursive factors in the Framingham Study. Neurology. 1984;34:847-854.

24 Sarti C, Tuomilehto J, Salomaa V, et al. Epidemiology of subarachnoid hemorrhage in Finland from 1983 to 1985. Stroke. 1991;22:848-853.

25 Fogelholm R, Hernesniemi J, Vapalahti M. Impact of early surgery on outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. A population-based study. Stroke. 1993;24:1649-1654.

26 Ingall TJ, Whisnant JP, Wiebers DO, et al. Has there been a decline in subarachnoid hemorrhage mortality? Stroke. 1989;20:718-724.

27 Rinne J, Hernesniemi J, Niskanen M, et al. Analysis of 561 patients with 690 middle cerebral artery aneurysms: anatomic and clinical features as correlated to management outcome. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:2-11.

28 Tsutsumi K, Ueki K, Morita A, et al. Risk of rupture from incidental cerebral aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:550-553.

29 Mizoi K, Yoshimoto T, Nagamine Y, et al. How to treat incidental cerebral aneurysms: a review of 139 consecutive cases. Surg Neurol. 1995;44:114-120.

30 Mount LA, Brisman R. Treatment of multiple aneurysms—symptomatic and asymptomatic. Clin Neurosurg. 1974;21:166-170.

31 Sampei T, Mizuno M, Nakajima S, et al. [Clinical study of growing up aneurysms: report of 25 cases.]. No Shinkei Geka. 1991;19:825-830.

32 Richardson AE, Jane JA, Payne PM. Assessment of the natural history of anterior communicating aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1964;21:266-274.

33 Richardson AE, Jane JA, Yashon D. Prognostic factors in the untreated course of posterior communicating aneurysms. Arch Neurol. 1966;14:172-176.

34 Winn HR, Richardson AE, Jane J, editors. The Assessment of the Natural History of Single Aneurysms That Have Ruptured. New York: Raven Press. 1982:1-10.

35 Weir B, editor. Aneurysms Affecting the Nervous System. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1987.

36 McCormick W. The natural history of intracranial saccular aneurysms: an autopsy study. Neurol Neurosurg. 1978;1:1-8.

37 Stehbens WE. Aneurysms and anatomical variation of cerebral arteries. Arch Pathol. 1963;75:45-64.

38 Stehbens WE. Pathology of the Cerebral Blood Vessels. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1972.

39 Philips L, Whisnant J, O’Fallon W, et al. The unchanging pattern of subarachnoid hemorrhage in a community: influence of arterial hypertension and gender. Neurology. 1980;30:1034-1040.

40 Inagawa T. Risk factors for the formation and rupture of intracranial saccular aneurysms in Shimane, Japan. World Neurosurg. 2010:155-164.

41 Sandvei MS, Romundstad PR, Muller TB, et al. Risk factors for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in a prospective population study: the HUNT study in Norway. Stroke. 2009;40:1958-1962.

42 Weir BK, Kongable GL, Kassell NF, et al. Cigarette smoking as a cause of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and risk for vasospasm: a report of the Cooperative Aneurysm Study. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:405-411.

43 Matsumoto K, Akagi K, Abekura M, et al. [Cigarette smoking increases the risk of developing a cerebral aneurysm and of subarachnoid hemorrhage.]. No Shinkei Geka. 1999;27:831-835.

43a Qureshi AI, Sung GY, Suri MF, et al. Factors associated with aneurysm size in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: effect of smoking and aneurysm location. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:44-50.

44 Feigin VL, Rinkel GJ, Lawes CM, et al. Risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage: an updated systematic review of epidemiological studies. Stroke. 2005;36:2773-2780.

45 McCormick WF, Nofzinger JD. Saccular intracranial aneurysms: an autopsy study. J Neurosurg. 1965;22:155-159.

46 Wills S, Ronkainen A, van der Voet M, et al. Familial intracranial aneurysms: an analysis of 346 multiplex Finnish families. Stroke. 2003;34:1370-1374.

47 Peck G, Smeeth L, Whittaker J, et al. The genetics of primary haemorrhagic stroke, subarachnoid haemorrhage and ruptured intracranial aneurysms in adults. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3691.

48 Bilguvar K, Yasuno K, Niemela M, et al. Susceptibility loci for intracranial aneurysm in European and Japanese populations. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1472-1477.

49 Kilic T, Sohrabifar M, Kurtkaya O, et al. Expression of structural proteins and angiogenic factors in normal arterial and unruptured and ruptured aneurysm walls. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:997-1007.

50 Nahed BV, Bydon M, Ozturk AK, et al. Genetics of intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:213-225.

51 Nahed BV, Seker A, Guclu B, et al. Mapping a mendelian form of intracranial aneurysm to 1p34.3-p36.13. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:172-179.

52 Ozturk AK, Nahed BV, Bydon M, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of two large kindreds with intracranial aneurysms demonstrates linkage to 11q24-25 and 14q23-31. Stroke. 2006;37:1021-1027.

53 Ong AC. Screening for intracranial aneurysms in ADPKD. BMJ. 2009;339:3763.

54 Pirson Y, Chauveau D, Torres V. Management of cerebral aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:269-276.

55 Leblanc R. Familial cerebral aneurysms. Can J Neurol Sci. 1997;24:191-199.

56 Bromberg JE, Rinkel GJ, Algra A, et al. Subarachnoid haemorrhage in first and second degree relatives of patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:288-289.

57 Greebe P, Bromberg JE, Rinkel GJ, et al. Family history of subarachnoid haemorrhage: supplemental value of scrutinizing all relatives. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:273-275.

58 ter Berg HW, Dippel DW, Limburg M, et al. Familial intracranial aneurysms. A review. Stroke. 1992;23:1024-1030.

59 Teunissen LL, Rinkel GJ, Algra A, et al. Risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review. Stroke. 1996;27:544-549.

60 ter Laan M, Kerstjens-Frederikse WS, Metzemaekers JD, et al. Concordant symptomatic intracranial aneurysm in a monozygotic twin: a case report and review of the literature. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2009;12:295-300.

61 Wermer MJ, van der Schaaf IC, Algra A, et al. Risk of rupture of unruptured intracranial aneurysms in relation to patient and aneurysm characteristics: an updated meta-analysis. Stroke. 2007;38:1404-1410.

62 McKissock W, Richardson A, Walsh L. Posterior-communicating aneurysms: a controlled trial of the conservative and surgical treatment of ruptured aneurysms of the internal carotid artery at or near the point of origin of the posterior communicating artery. Lancet. 1960;1:1203-1206.

63 McKissock W, Richardson A, Walsh L. Anterior communicating aneurysms: a trial of conservative and surgical treatment. Lancet. 1965;1:874-876.

64 McKissock W, Richardson AE, Walsh L. Middle-cerebral aneurysms. Further results in the controlled trial of conservative and surgical treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Lancet. 1962;2:417-420.

65 Nishioka H. Report on the Cooperative Study of Intracranial Aneurysms and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Section VII. I. Evaluation of the conservative management of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:574-592.

66 Nishioka H. Results of the treatment of intracranial aneurysms by occlusion of the carotid artery in the neck. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:660-704.

67 Perret G, Nishioka H. Report on the cooperative Study of Intracranial Aneurysms and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Section VI. Arteriovenous malformations. An analysis of 545 cases of cranio-cerebral arteriovenous malformations and fistulae reported to the cooperative study. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:467-490.

68 Perret G, Nishioka H. Report on the Cooperative Study of Intracranial Aneurysms and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. IV. Cerebral angiography. An analysis of the diagnostic value and complications of carotid and vertebral angiography in 5,484 patients. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:98-114.

69 Sahs AL, Perret G, Locksley HB, et al. Preliminary remarks on subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1966;24:782-788.

70 Longstreth WTJr, Nelson LM, Koepsell TD, et al. Clinical course of spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage: a population-based study in King County, Washington. Neurology. 1993;43:712-718.

71 Winn HR, Richardson AE, Jane JA. The long-term prognosis in untreated cerebral aneurysms: I. The incidence of late hemorrhage in cerebral aneurysm: a 10-year evaluation of 364 patients. Ann Neurol. 1977;1:358-370.

72 Hunt WE, Hess RM. Surgical risk as related to time of intervention in the repair of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1968;28:14-20.

73 Lagares A, Gomez PA, Lobato RD, et al. Prognostic factors on hospital admission after spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2001;143:665-672.

74 Alvord ECJr, Loeser JD, Bailey WL, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage due to ruptured aneurysms. A simple method of estimating prognosis. Arch Neurol. 1972;27:273-284.

75 Leung CH, Poon WS, Yu LM, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and outcome in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2002;33:548-552.

76 Pobereskin LH. Incidence and outcome of subarachnoid haemorrhage: a retrospective population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:340-343.

77 Kassell NF, Torner JC. Aneurysmal rebleeding: a preliminary report from the Cooperative Aneurysm Study. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:479-481.

78 Fujii Y, Takeuchi S, Sasaki O, et al. Ultra-early rebleeding in spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:35-42.

79 Longstreth WT, Nelson LM, Koepsell TD, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage and hormonal factors in women. A population-based case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:168-173.

80 Naidech AM, Janjua N, Kreiter KT, et al. Predictors and impact of aneurysm rebleeding after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:410-416.

81 He W, Hauptman J, Pasupuleti L, et al. True posterior communicating artery aneurysms: are they more prone to rupture? A biomorphometric analysis. J Neurosurg. 2010;112:611-615.

82 Ma B, Lu J, Harbaugh RE, et al. Nonlinear anisotropic stress analysis of anatomically realistic cerebral aneurysms. J Biomech Eng. 2007;129:88-96.

83 Zhou X, Raghavan ML, Harbaugh RE, et al. Patient-specific wall stress analysis in cerebral aneurysms using inverse shell model. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:478-489.

84 Khurana VG, Meissner I, Sohni YR, et al. The presence of tandem endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphisms identifying brain aneurysms more prone to rupture. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:526-531.

85 Khurana VG, Sohni YR, Mangrum WI, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphisms predict susceptibility to aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral vasospasm. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:291-297.

86 McKissock W, Richardson A, Walsh L, et al. Multiple intracranial aneurysms. Lancet. 1964;1:623-626.

87 McKissock W, Walsh L. Subarachnoid haemorrhage due to intracranial aneurysms; results of treatment of 249 verified cases. Br Med J. 1956;2:559-565.

88 Richardson AE, Jane JA, Payne PM. The prediction of morbidity and mortality in anterior communicating aneurysms treated by proximal anterior cerebral ligation. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:280-283.

89 Graf CJ. Prognosis for patients with nonsurgically-treated aneurysms. Analysis of the Cooperative Study of Intracranial Aneurysms and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1971;35:438-443.

90 Winn HR, Richardson AE, O’Brien W, et al. The long-term prognosis in untreated cerebral aneurysms: II. Late morbidity and mortality. Ann Neurol. 1978;4:418-426.