CHAPTER 13 The multi-vectored rhytidoplasty

The stigmata of facial aging are well known. They include loss of elasticity and laxity of the cheeks, jowl formation, perioral wrinkles, platysmal bands, and laxity of cervical skin. The possible combinations are infinite, and each patient must be carefully analyzed to formulate a treatment plan. Our challenge as plastic surgeons is to recreate harmony between facial regions and to balance and smoothly blend the transition between these regions. It is important to ascertain what patients looked like early in their lives. Several questions then arise for the plastic surgeon. Do the patients themselves remember? Do we restore their youthful appearance? Do we make them look different, or even better? It is also important to keep in mind that not everyone needs to have everything corrected.

My goals in choosing a procedure for facial rejuvenation are:

• It must provide reproducible results with repeated use.

• It must allow familiarity with easily mastered techniques.

• It must be able to be performed in a reasonable time at a reasonable cost.

• It must meet the patient’s goals.

• The technique must be equally applicable for primary and secondary procedures.

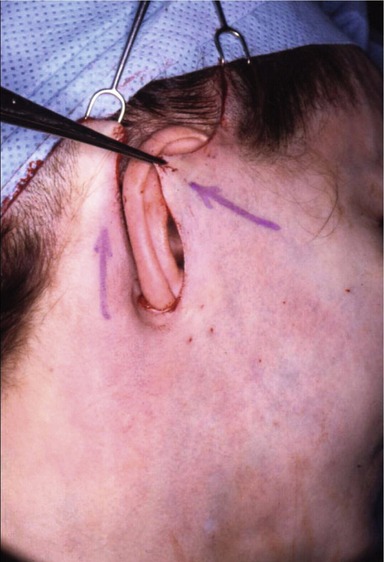

The facialplasty is begun by undermining the right side of the face and neck and then the left side. The submental, anterior, and lateral aspects of the neck are undermined and defatted as necessary. Bands may be excised vertically and/or transected transversely (inferiorly), and then the SMAS in the left and right cheeks and neck is tightened. Finally, the submental incision is closed and the flaps on the right and left sides of the face and neck are redraped, the excess skin is excised and the incisions are closed. The incisions must be placed so that they will heal well, and great attention to technique and detail will result in scars that will be almost imperceptible. It does not matter how long the scar is, it matters where it is, and how it looks! (see Fig. 13.1).

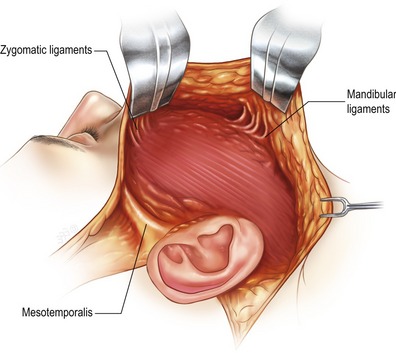

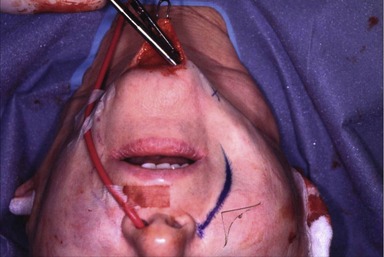

Laxity in the lower face and submental areas develops because of loss of support from the SMAS, and especially because of loss of elasticity of the skin and its attachments to the deeper tissues, except where attached to the facial skeleton by the osseocutaneous ligaments. These ligaments do not become lax with time and are the cause for some of the deformities seen in the aging face due to the descensus of the soft tissues, such as the lateral perioral labiomandibular creases and formation of jowls. Therefore it is important to release the zygomatic and mandibular osseocutaneous ligaments (see Figs 13.2, 13.3, and 13.4).

I used to believe that to decrease the prominence of the nasolabial folds and creases it was necessary to do a supra-SMAS dissection medial to the nasolabial fold to allow redraping and produce effacement (see Fig. 13.5). Now I believe that it is preferable to leave the skin and subcutaneous tissues attached to the underlying SMAS medially, so that when it is redraped the nasolabial fold will be less evident and the crease effaced. Dissection only in the sub-SMAS plane prohibits fat contouring in the labiomandibular fold and jowls, especially in an overweight patient. Removal of the subcutaneous adipose tissue in the neck provides improvement in contour, especially when present in excess in an overweight individual, but care must be taken to remove fat in the face in moderation (if at all), especially in a younger, thinner person. Remember that the subcutaneous adipose tissues atrophy as aging progresses (see Fig. 13.6).

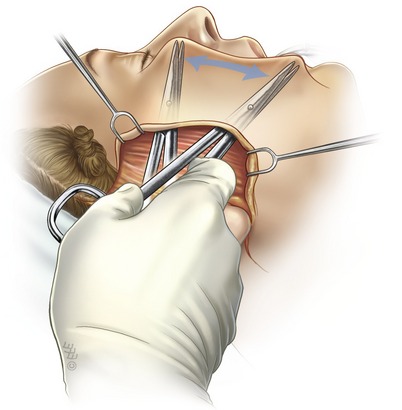

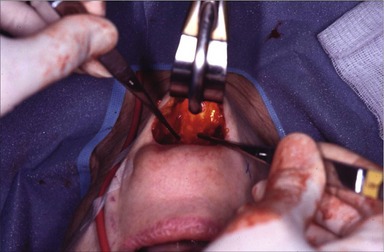

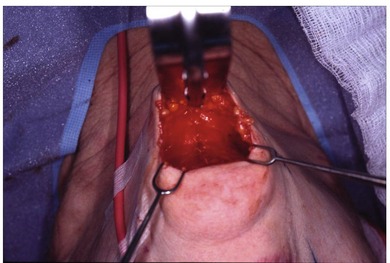

For ultimate improvement in the contour of the neck, the platysma needs to be strengthened and utilized as a sling or corset to improve the cervicomental angle, making it more acute. Bringing the two platysma muscles together in the midline (submental, anterior cervical) and tightening and slightly lifting the lateral, posterior border elevates the soft tissues of the neck, including ptotic submandibular glands, obviating the need to partially remove or excise them or the muscles in the submental region (see Figs 13.7, 13.8 and 13.9).

The main surgical objective is to perform a multi-vectored bi-directional resetting of the skin/subcutaneous tissue flap and of the SMAS flap with different tensions to achieve a more youthful appearance (see Figs 13.10, 13.11). This is not possible with a deep plane or composite procedure because all of the tissues are mobilized and moved as a single unit.

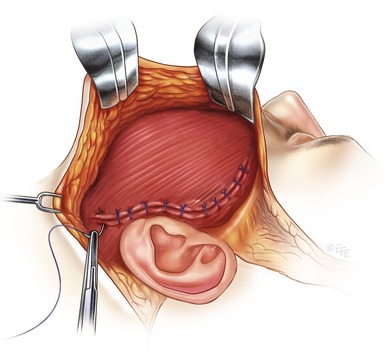

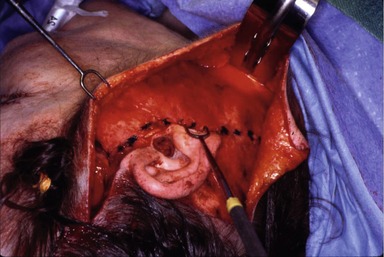

The need to manipulate the SMAS seems to be generally accepted, however the best method continues to be controversial. My choices for SMAS tightening include plication, lateral SMAS-ectomy, or an extended SMAS flap with or without a post-auricular extension. Permanent sutures of 3-0 Mersilene are used, and they are tiered if necessary. The SMAS tension is set supero-laterally (see Figs 13.12, 13.13). The skin vector is set opposite to the SMAS vector, perpendicular to the nasolabial crease. The preauricular closure is tension-free. The face and neck are “hung” by key tension sutures, which are placed in the superior preauricular and postauricular region, not by the earlobe (see Figs 13.14, 13.15). For perfect scars with no trace of operation behind the ears, 4-0 nylon vertical mattress sutures are placed to approximate the postauricular flap into the sulcus. It is necessary to adjust the posterior retromastoid hairline to avoid a step-off. The earlobe is replaced and repositioned with a vertical mattress suture to the underlying non-mobile deep tissues so that it will not wander inferiorly (see Figs 13.16, 13.17, and 13.18). I prefer to dissect and redrape the tissues in a superficial rather than a deep plane because I have not ever believed that the periosteum or its soft tissue attachments become loose with advancing age. For this reason, it has not made sense to me to perform subperiosteal release of a composite of tissues in order to correct the laxity which has occurred in the more superficial tissues.

The following are my thoughts about some new ideas being presented for facial rejuvenation. Increasing the volume of the external tissues of the face by the subcutaneous injection of fat or filling materials is not a permanent solution for long-lasting rejuvenation. Initial improvement is temporary at best. The procedure has to be repeated for maintenance of results and therefore I feel that this should be considered ancillary rather than primary.

Duffy MJ, Friedland JA. The superficial plane rhytidectomy revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:1392.

Friedland JA, Jacobsen WM, TerKonda S. The safety and efficacy of combined upper blepharoplasties and open coronal browlift: a consecutive series of 600 patients. Aesth Plast Surg. 1996;20:453–462. –

Friedland JA. Superficial/skin level rhytidectomy provides safe, superior facial contouring. Aesth Surg J. 1998;18:226.

Friedland JA. The cutaneous rhytidectomy. In: Bernard R, ed. Surgical restoration of the aging face. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1996.

Friedland JA. Rhytidectomy: the superficial plane. Operat Tech Plast Surg. 1995;2:89.

Friedland JA, Smith JW, Evaluation of the aging face. Weinzweig J, ed. Plastic surgery secrets, 2nd edn, Philadelphia, PA: Hanley & Belfus, 1999.

xylocaine with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine.

xylocaine with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine.