Chapter 9 The medical literature

This chapter is presented in three parts:

Part A: the emergency physician’s guide to basic statistics

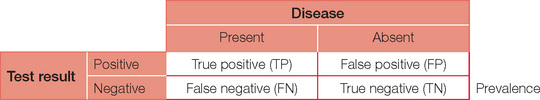

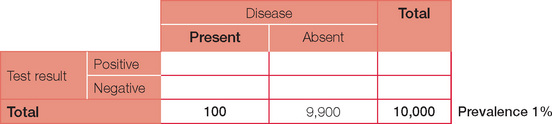

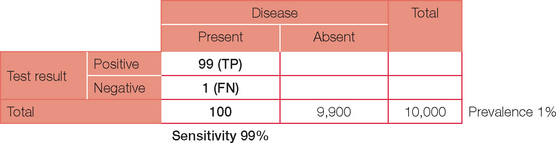

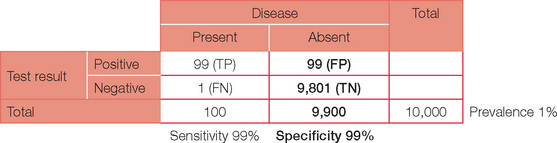

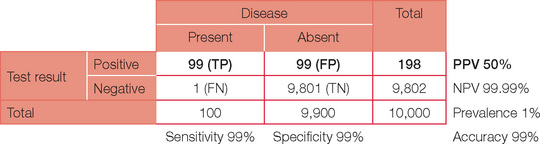

The table can now be completed with simple arithmetic.

Accuracy = (TP + TN)/(TP + TN + FP + FN)

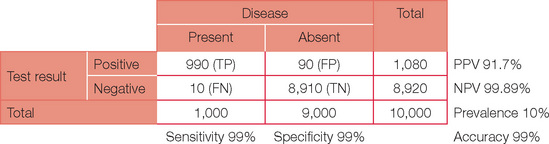

Below is the original question with a prevalence of 10%.

Note, the PPV has now increased dramatically. If your confidence in basic statistics has now grown (and your headache has gone), try different combinations and permutations of parameters to confirm the effect on PPV and NPV. To start with, review a paper or even work through the detail for an investigation you perform on a regular basis. You may never view basic statistics with fear again!

Part B: an overview of EBM

The context

This excerpt from an editorial by Davidoff et al. in the BMJ in 1995 still holds true today. EBM comprises the latest information on the most effective or least harmful management for patients (Davidoff et al., 1995). The key processes in EBM are:

Critical appraisal is ‘the process of systematically examining research evidence to assess its validity, results and relevance before using it to inform a decision’ (Mark, 2008). It allows the reader to assess in a systematic way how strong or weak a paper is in answering a clinically relevant question or whether the paper can be relied on as the basis for making clinical decisions for patients.

Most readers will not limit their literature search in terms of date of publication (when) unless they are confident that a treatment or test was developed only recently, or an unlimited search yields numerous citations, which become unmanageable. As there is often a time lag between study citations being added to searchable databases, it is worthwhile considering conducting a more recent targeted search in relevant journals if the topic area is rapidly evolving. Wang and Bakhai (2006) and Pocock (1983) provide excellent further reading in the area of clinical trials, as do Greenhalgh’s ‘Education and debate’ series from the BMJ (Greenhalgh, 1997a) and Gordon Guyatt’s 2000 focus series from the JAMA (Guyatt, 2000).

Before looking for individual studies, we recom mend a concerted search for metaanalyses, which offer a useful background perspective and, if one is lucky, may even answer the research question, using the summated ‘quality overall evidence’ available so far (Mark, 2008). Meta-analyses are formally designed and properly conducted critical appraisals of intervention trials that attempt to ‘aggregate’ outcome findings from individual studies if they show a consistent effect. The presence of compelling outcome effects, consistent in direction and size across individual non-clinically heterogeneous studies of acceptable methodological quality, will likely be enough to tell you whether a proposed treatment or diagnostic test will be suited to your patient.

Critically appraising a meta-analysis will still save you time and effort if many intervention trials or studies of diagnostic performance of a certain test relevant to your objective have been carried out. You need to ascertain whether the methodological rigour and quality of the meta-analysis is sufficient for conclusions and recommendations contained in the meta-analysis to reliably fulfil your objectives. If a well-conducted and reported meta-analysis is available, re-examining individual studies in detail is less worthwhile, other than for personal interest. However, a meta-analysis will not include influential studies that become available after the date of publication of the metaanalysis. Carrying out a date-of-publication limited search for newly emerging studies is thus recommended, to see whether the conclusions reached in the meta-analysis remain consistent with the newer studies. For in-depth information on systematic reviews in health care, see the standard text by Matthias Egger et al. (2001).

Critical appraisal and clinical practice

In emergency medicine, critical appraisal of the evidence is most pertinent to time-critical conditions that require non-established or contentious urgent treatments that may be highly beneficial but also lead to significant harm. For example, this situation arises in thrombolytic treatment for acute ischaemic stroke, where treatment administered within three hours of symptom onset gives better neurofunctional outcome, but remains little used for fear of causing intracranial bleeding. ECASS III, a recently published RCT comparing IV alteplase with a placebo in ischaemic stroke, found alteplase to remain beneficial at three to four and a half hours after symptom onset (Hacke et al., 2008). The most recent Cochrane meta-analysis of thrombolysis trials in stroke, published in 2003, did not include ECASS III (Wardlaw et al., 2003). Evidence is in a constant state of evolution, so critical appraisal is a continuing process that aligns itself with continuing medical education and professional development. Nowadays, studies informing on therapeutic (in) effectiveness are easily and rapidly accessible through user-friendly information technology media such as the 24-hour medical cybrary. With the exception of acute resuscitation, there is never an excuse not to evaluate effectiveness prior to patient treatment.

Levels of evidence

Intervention and non-intervention studies can be stratified into several ‘levels of evidence’, according to their internal validity and dependability in informing treatment effects. A well-designed and conducted meta-analysis or randomised controlled blinded treatment trial is widely recognised as being able to offer the most reliable and least biased estimate of treatment benefit or harm (Wang et al., 2006), followed in descending order of quality of evidence by observational non-intervention studies such as case control studies and finally case series and case reports. This is variously graded (e.g. levels I–IV or grade A–C recommendations) depending on the body utilising this. Several issues should be apparent at this stage:

A tool kit of EBM techniques

Critical appraisal of a single intervention study

Critical appraisal requires the following questions to be satisfactorily answered.

What is the research question?

P study participant characteristics at baseline, including disease severity; study setting

I experimental intervention or diagnostic test being investigated

C comparison or control group, usually the standard treatment/test, a placebo or usual care

O outcomes of interest; clinically meaningful for both the clinician and patient

T time period of the study observation or period of follow-up.

Are the study results likely to be valid?

Was the trial design valid?

Was the conduct of the trial valid?

Was the analysis of the trial findings valid?

Intention to treat analysis

All patients should be analysed in the group to which they were randomised. Loss to follow-up greater than 20%, especially if differentially distributed between groups, will lead to post-randomisation bias if intention to treat (ITT) analysis is not used. ITT analysis means that patients are analysed according to the treatment group to which they were random ised, irrespective of whether they underwent the intended intervention or whether they adhered to protocol stipulations. ITT analysis results in an unbiased estimate of effect and more closely reflects what happens in reallife clinical practice, where patients have a range of compliance with treatment recommendations. In contrast, per protocol analysis is biased, since it includes only comparisons between patients who adhere to the treatment allocated to them. If the tested treatment works, the measured effect of the same treatment in the same study will be greater in magnitude for per protocol analysis (where only compliant patients are included in the analy sis) compared with ITT analysis (where all patient outcomes are included in the analysis whether patients comply with the treatment or not).

Statistical method

The use of post-hoc subgroup analyses, unjustified multiple outcome or interim comparisons will likely lead to a false positive finding in a small study subset (the more analyses are done, the more the risk of a false positive finding). However, it is reasonable to conduct post-hoc analysis adjustments if results indicate the method initially chosen is no longer valid. For example, a study may have been designed expecting normally distributed data, but non-normal distribution of data is unexpectedly encountered. In this situation, non-parametric methods will be required. Interested readers are referred to standard texts (Kirkwood et al., 2003) and user-friendly articles (Greenhalgh 1997b; 1997c).

What are the results?

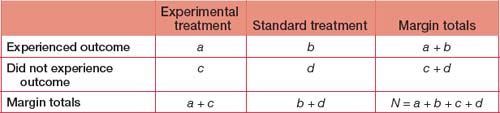

Measures of treatment effect

Number needed to treat

When we look at treatment benefit, the NNT to benefit is equivalent to (1/absolute risk difference). It is clear from this formula that the greater the absolute risk difference conferred by a treatment (the denominator), the smaller the number of patients required to be treated before one experiences a benefit. Using the previous example, where absolute risk difference is 2% benefit conferred by treatment X, the NNT for benefit is (1/0.02) = 50 for one patient to benefit. Although the relative risk of a benefit is 200% when X is compared with Y, 50 patients must be treated with X to obtain benefit for one, reflecting the small absolute risk benefit conferred by X.

How might the results be applied?

An example of the application of these statistical factors and their clinical relevance is provided in Table 9.1 pertaining to the ECASS III study. A reasonable interpretation of this study could be that:

… for adult stroke patients similar to those enrolled in ECASS III (18–80 years admitted to a stroke centre with a diagnosis of acute ischaemic stroke able to receive the study drug within three to four hours after symptom onset), the number needed to treat to achieve a neurofunctional benefit (1 in 14) is far fewer than that required to harm (1 in 46 will suffer symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage). Despite increased risk of intracranial haemorrhage with alteplase, there was no mortality difference.

Source:Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1317−1329.

Critical appraisal of meta-analyses

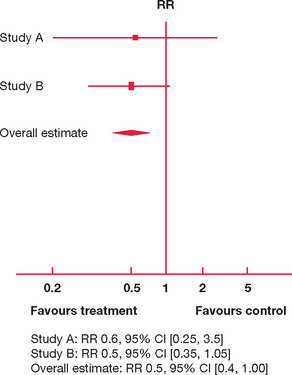

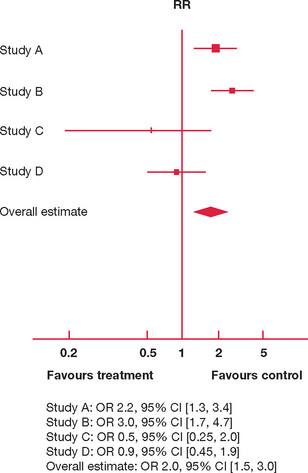

We present two hypothetical meta-analyses for interventions to reduce the risk of failing the fellow ship examination in Figures 9.1 and 9.2.

In Figure 9.1 there are only two studies available, A and B. Both studies have the majority of their 95% CI consistently to one side (left) of the vertical line of no effect. Both A and B are suggestive that an 18-month study phase reduces risk of failure (the risk ratio of failure is 0.6 and 0.5, respectively, with most of the 95% CI to the left of the vertical line). However, the upper limit of 95% CIs for A and B also extends to the right of the vertical line, so that an 18-month study phase may well increase the risk of failure by a factor of 3.5 and 1.05, respectively.

In Figure 9.2 there are four studies comparing the effect of attendance at weekly teaching sessions for six months and taking a three-month overseas holiday on failure in the fellowship examination. The individual study effects are inconsistent:

However, since the effect estimations and 95% CI for individual studies are so variable, is it appropriate to aggregate their results in producing an overall estimate?

Part C: important papers

This section is divided into three groups of papers. First, brief synopses of a selection of important original studies and meta-analyses are presented together with their substantial contribution to evidence-based clinical practice in emergency medicine. These are not presented in any particular order, since all articles in this collection are deemed to be equally important. Next, some papers highlighting controversies and unanswered questions are provided to stimulate you to consider areas of ongoing debate. Some of the issues raised may surprise those who are unaware that the level of evidence supporting some widely employed therapies is not as robust as they once thought. Finally, useful resources that combine evidence from multiple sources into easy-to-use practice recommendations are presented. We encourage you to add to all of these sections during your exam preparations.

Lessons from original papers that have shaped emergency medicine

The Australian investigators are currently studying whether pre-hospital cooling by ambulance paramedics will add any additional benefit. The first of these trials was ceased during interim analysis for futility regarding benefit. With methodological changes, particularly earlier cooling, this remains an area of active research.

Controversies and unanswered questions

ATLS

Interested readers may access further information regarding these most recent changes from http://web15.facs.org/atls_cr/atls_8thEdition_Update.cfm.

Should steroids be given to patients with traumatic spinal cord injuries?

Is hypertonic saline the fluid of choice for patients with traumatic brain injury?

What is the role for recombinant factor VIIa in ED patients?

Is hypotensive resuscitation appropriate for some trauma patients?

What is the best method for reducing anterior shoulder dislocations?

Is needle aspiration a safe and effective treatment of a primary spontaneous pneumothorax?

What is the influence of BLS and ALS by paramedics on outcome in traumatic and non-traumatic conditions?

Is chest compression alone better than full CPR in cardiac arrest?

How should red-back spider (RBS) antivenom be administered?

How much antivenom is needed for brown snake envenomation?

Does octreotide successfully decrease acute bleeding from oesophageal varices?

Should hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy be used to treat patients with carbon monoxide poisoning?

Do hospital medical emergency teams (METs) improve the outcomes of critically ill patients?

Should EDs have a protocol regarding N-AC for prophylaxis against radiocontrast nephropathy?

Is there a role for levosimendan in ED?

Is there a role for new ‘point-of-care’ tests such as brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and procalcitonin in ED?

Should all patients with bacterial meningitis be treated with high-dose steroids?

The evidence for benefit from corticosteroids in adults with bacterial meningitis is less certain. In van de Beek’s meta-analysis, 18 studies involving 2,750 patients were analysed. Adjuvant steroids were associated with lower mortality, reduced rates of severe hearing loss and long-term neurologic sequelae. In children the most significant effects were on preventing hearing loss and in adults the most significant effects were greater protection from death. With steroids, mortality reduction was most noticeable in patients with Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis. Children with Haemophilus influenzae meningitis experienced the least risk of hearing loss:

Is lactulose an important component of supportive treatment for patients with decompensated liver failure?

Evidence-based practice recommendations

Life support

The most recent ILCOR guidelines on ACLS in adults and paediatrics (2005) can be found in:

Acute coronary syndromes

Other topics

Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Research, 1st edn. London: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1991.

Davidoff F, Haynes B, Sackett D, Smith R. Evidence based medicine. BMJ. 1995;310:1085-1086.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG. Systematic Reviews in Health Care. Metaanalysis in Context, 2nd edn. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 2001.

Greenhalgh T. Assessing the methodological quality of published papers. BMJ. 1997;315:305-308.

Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper. Statistics for the non-statistician. I: different types of data need different statistical tests. BMJ. 1997;315:364-366.

Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper. Statistics for the non-statistician. II: ‘significant’ relations and their pitfalls. BMJ. 1997;315:422-425.

Guyatt GH, Naylor D, Richardson WS, et al. What is the best evidence for making clinical decisions? JAMA. 2000;284:3127-3128.

Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317-1329. Sep25

Kirkwood BR, Sterne JAC. Essential Medical Statistics, 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2003.

Mark Daniel B. Chapter 3, ‘Decision-making in clinical medicine’. In Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, editors: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 17th edn., New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2008.

Pocock SJ. Clinical Trials. A Practical Approach, 1st edn. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1983.

Wang D, Bakhai A. Clinical trials. A Practical Guide to Design, Analysis and Reporting, 1st edn. London: Remedica; 2006.

Wardlaw JM, del Zoppo GJ, Yamaguchi T, Berge E. Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 3. Art. No. CD000213. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000213.