The Medical History and the Interview

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

1. Recognize the importance of properly obtaining and recording a patient history.

2. Describe the techniques for structuring the interview.

3. Summarize the techniques used to facilitate conversational interviewing.

4. Identify alternative sources available for the patient history.

5. Define the difference between objective and subjective data and the difference between signs and symptoms.

6. Describe the components of a complete health history and the type of information found in each section of the history.

7. Describe the value in reviewing the following parts of a patient’s chart: (1) admission notes, (2) physician orders, (3) progress notes.

8. Summarize what is indicated by a DNR order and label on the patient’s chart.

This chapter highlights interviewing principles and describes the types of questions used in history taking and the content of the comprehensive health history, emphasizing specific information needed for assessment of the patient with cardiopulmonary complaints. Chapter 3 discusses the most common cardiopulmonary symptoms.

Patient Interview

Principles of Communication

Communication is a process of imparting a meaningful message. The principles and practices of effective communication, which are outlined in Chapter 1, help form the basis for a properly conducted patient interview. Multiple personal and environmental factors affect the way both patients and health care professionals communicate during an interview. As a result, attention to the effects each of these components may have on communication makes the difference between an effective and an ineffective interview.

Structuring the Interview

1. Your introduction establishes your professional role, asks permission to be involved in the patient’s care, and conveys your interest in the patient.

• Dress and groom professionally.

• Enter with a smile and an unhurried manner.

• Make immediate eye contact, and if the patient is well enough, introduce yourself with a firm handshake or other appropriate greeting.

• State your role and the purpose of your visit, and define the patient’s involvement in the interaction.

• Call the patient by name. A person’s name is one of the most important things in the world to that person; use it to identify the patient and establish the fact that you are concerned with the patient as an individual. Address adult patients by title—Mr., Mrs., Miss, or Ms.—and their last name. Occasionally, patients will ask to be called by their first name or nickname, but that is the patient’s choice and not an assumption to be made by the health care professional. Keep in mind that by using the more formal terms of address, you alert the patient to the importance of the interaction.

2. Professional conduct shows your respect for the patient’s beliefs, attitudes, and rights and enhances patient rapport.

• Be sure the patient is appropriately covered.

• Position yourself so that eye contact is comfortable for the patient. Ideally, patients should be sitting up with their eye level with or slightly above yours, which suggests that their opinion is important, too. Avoid positions that require the patient to look directly into the light.

• Avoid standing at the foot of the bed or with your hand on the door while you talk with the patient. This may send the nonverbal message that you do not have time for the patient.

• Ask the patient’s permission before moving any personal items or making adjustments in the room (see Chapter 1).

• Remember, the patient’s dialogue with you and the patient’s medical record are confidential. The patient expects and the law demands that this information be shared only with other professionals directly involved in the patient’s care. When a case is discussed for teaching purposes, the patient’s identity should be protected.

• Be honest. Never guess at an answer or information you do not know. Remember, too, that you have no right to provide information beyond your scope of practice. Providing new information to the patient is the privilege and responsibility of the attending physician.

• Make no moral judgments about the patient. Set your values for patient care according to the patient’s values, beliefs, and priorities. Belittling or laughing at a patient for any reason is unprofessional and unacceptable.

• Be mindful and respectful of cultural, ethnic, religious, and other forms of diversity (see Chapter 1).

• Expect a patient to have an emotional response to illness and the health care environment and accept that response. Listen, then clarify and teach, but never argue. If you are not prepared to explore the issues with the patient, contact someone who is.

• Adjust the time, length, and content of the interaction to your patient’s needs. If the patient is in distress, obtain only the information necessary to clarify immediate needs. It may be necessary to repeat some questions later, to schedule several short interviews, or to obtain the information from other sources.

3. A relaxed, conversational style on the part of the health care professional with questions and statements that communicate empathy encourages patients to express their concerns.

• Expect and accept some periods of silence in a long or first interview. Both you and the patient need short periods to think out the correct responses.

• Close even the briefest interview by asking if there is anything else the patient needs or wants to discuss and telling the patient when you will return.

Questions and Statements Used to Facilitate Conversational Interviewing

1. Open-ended questions encourage patients to describe events and priorities as they see them and thereby help bring out concerns and attitudes and promote understanding. Questions such as “What prompted you to come to the hospital?” or “What happened next?” encourage conversational flow and rapport while giving patients enough direction to know where to start.

2. Closed questions such as “When did your cough start?” or “How long did the pain last?” focus on specific information and provide clarification.

3. Direct questions can be either open-ended or closed questions and always end in a question mark. Although they are used to obtain specific information, a series of direct questions or frequent use of “Why?” can sound intimidating.

4. Indirect questions are less threatening because they sound like statements: “I gather your doctor told you to monitor your peak expiratory flow rates every day.” Inquiries of this type also work well to confront discrepancies in the patient’s statements: “If I understood you correctly, it is harder for you to breathe now than it was yesterday.”

5. Neutral questions and statements are preferred for all interactions with the patient. “What happened next?” and “Tell me more about . . .” are neutral open-ended questions. A neutral closed question might give a patient a choice of responses while focusing on the type of information desired: “Would you say there was a teaspoon, a tablespoon, or a half-cup?” By contrast, leading questions such as “You didn’t cough up blood, did you?” should be avoided because they imply a desired response.

6. Reflecting (echoing) is repeating words, thoughts, or feelings the patient has just stated and is a successful way to clarify and stimulate the patient to elaborate on a particular point. For example, saying to the patient that “So you just said that you could not breathe well and your cough was getting worse for about a week,” might encourage the patient to elaborate on these and other symptoms. However, overuse of reflecting can make the interviewer sound like a parrot.

7. Facilitating phrases, such as “yes” or “umm” or “I see,” used while establishing eye contact and perhaps nodding your head, show interest and encourage patients to continue their story, but this type of phrase should not be overused.

8. Communicating empathy (support) with statements like “That must have been very hard for you” shows your concern for the patient as a human being. Showing the patient that you really care about how life situations have caused stress, hurt, or unhappiness tells the patient it is safe to risk being honest about real concerns. Other techniques for showing empathy are described in Chapter 1.

Cardiopulmonary History and Comprehensive Health History

Variations in Health Histories

Health (medical) histories vary in length, organization, and content, depending on the preparation and experience of the interviewer, the patient’s age, the reason for obtaining the history, and the circumstances surrounding the visit or admission. A history taken for a 60-year-old person complaining of chronic and debilitating symptoms is much more detailed and complex than that obtained for a summer camp application or a school physical examination. Histories recorded in emergency situations are usually limited to describing events surrounding the patient’s immediate condition. In such situations, it is often difficult to get a thorough history, unless the patient is accompanied by someone who can speak on their behalf. Nursing histories emphasize the effect of the symptoms on activities of daily living and the identification of the unique care, teaching, and emotional support needs of the patient and family. Histories performed by physicians often focus on making a diagnosis. Since diagnosis and initial treatment may be done before there is time to dictate or record the history, the experienced physician may record data obtained from a combination of the history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and x-ray films rather than the more traditional history outlined in Box 2-1.

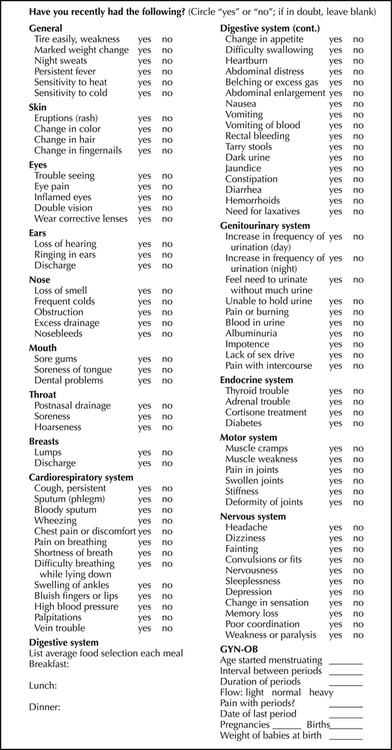

Review of Systems

Review of systems (ROS) is a recording of past and present information that may be relevant to the present problem but might otherwise have been overlooked. It is grouped by body or physiologic systems to guarantee completeness and to assist the examiner in arriving at a diagnosis. Figure 2-1 is an example of an ROS checklist that may be completed by a patient before an interview or by an examiner. It provides for recording both positive and negative responses so that when the documentation is later reviewed, there is no doubt as to which questions were asked. Negative responses to important questions asked at any time during the interview are termed pertinent negatives; affirmative responses are termed pertinent positives. For example, if a patient complains of acute coughing but denies any fever, the fever would represent a pertinent negative, whereas the cough is a pertinent positive.