CHAPTER 50 The mechanism of continence

Urinary Incontinence

Anatomy of the lower urinary tract

The pelvic floor

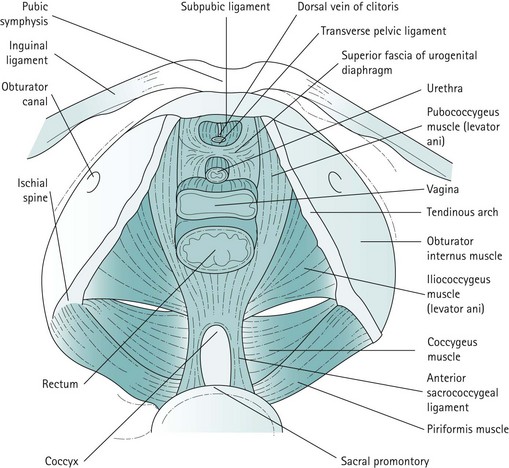

For the context of this chapter, the pelvic floor structures that will be described are the levator ani muscles, the endopelvic fascia and condensations of this fascia which form the ligaments. The levator ani muscles are often described as funnel-shaped structures, but in-vivo imaging has revealed that they are, in fact, more horizontal. The fibres of each side pass downwards and inwards. The two muscles, one on each side, constitute the pelvic diaphragm. Defects in the levator ani allow the urethra, vagina and rectum to pass. The levator ani is subdivided into the pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus and coccygeus. The pubococcygeus arises anteriorly from the posterior aspect of the pubic bone and from the anterior portion of the arcus tendineus (white line), which is a condensation of the obturator internus fascia. The medial fibres of the pubococcygeus merge with the fibres of the vagina and perineal body, and have been given various names such as puborectalis, pubourethralis and pubovaginalis. The iliococcygeus arises from the remainder of the arcus tendineus, partly overlapping the pubococcygeus on its perineal surface and extending to the medial surface of the ischial spine. The coccygeus or ischiococcygeus is a rudimentary muscle arising from the tip of the ischial spine, and quite often constitutes only a few muscle fibres on the sacrospinous ligament. Posteriorly, the muscles of the levator ani or pelvic diaphragm insert into the sides of the coccyx and the anococcygeal raphe, which is formed by the interdigitation of muscle fibres from either side. The most medial fibres of the pubococcygeus that pass round the rectum at the anorectal junction form the puborectalis muscle (Figure 50.1).

Innervation of the bladder and urethra

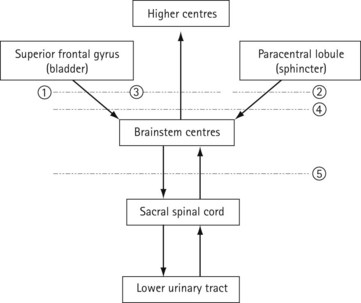

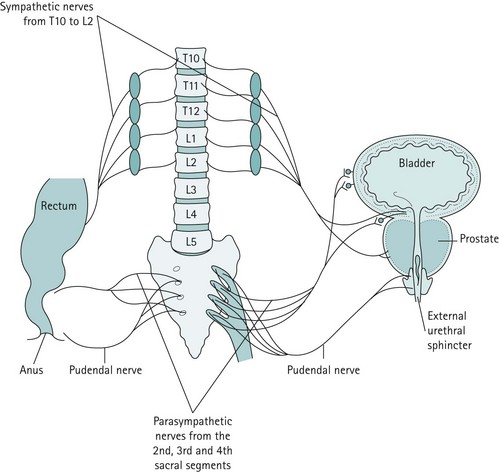

The bladder has a rich parasympathetic nerve supply (Figure 50.2). The postganglionic cell bodies lie either in the bladder wall or pelvic plexuses, innervated by preganglionic fibres that originate from cell bodies in the grey columns of S2–4. There is little sympathetic innervation of the bladder, although greater quantities of noradrenergic terminals can be detected in the bladder neck or trigone. Noradrenergic effects can be either inhibitory or excitatory, depending on the receptor type present.

Figure 50.2 The major innervation pathways at the pelvic level that are basic to control of micturition and continence.

Central nervous control of continence

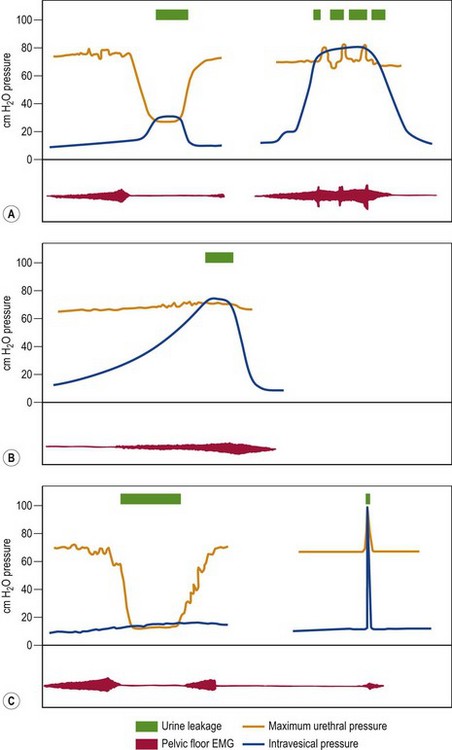

The connections of the lower urinary tract within the central nervous system are complex (Figure 50.3). There are many discrete areas which influence micturition, and these have been identified within the cerebral cortex, in the superior frontal and anterior cingulate gyri of the frontal lobe and the paracentral lobule; within the cerebellum, in the anterior vermis and fastigial nucleus; and in subcortical areas, including the thalamus, the basal ganglia, the limbic system, the hypothalamus and discrete areas of the mesencephalic pontine medullary reticular formation. The full function and interactions of these various areas are incompletely understood, although the effects of ablation and tumour growth in humans and stimulation studies in animals have given some insights.

The mechanism of urinary continence

Bladder

Urethra

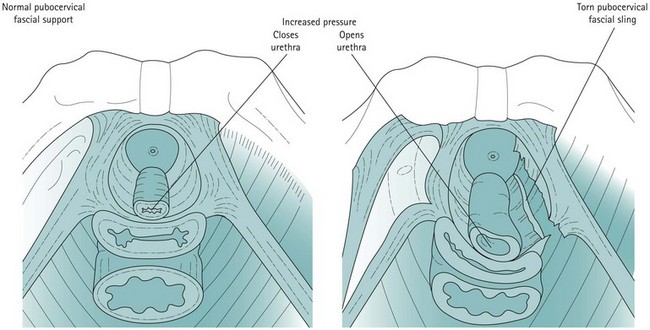

Urethral support

From cadaveric studies, ultrasound and MRI, it is postulated that the urethra is supported by a hammock (Figure 50.4). This hammock is contributed to by its immediate intimate relationship with the vagina, and the pubocervical fascia that lies between them and attaches laterally to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, which attaches to muscle fascia and which are in connection with the levator ani muscles themselves. During any rise in abdominal pressure, these may cause compression of the urethra against the anterior vaginal wall. In this model, it is the stability of the supporting structures rather than the height of the urethra that determines stress continence. In an individual with a firm supportive layer, the urethral compression can be compared with the way that the flow of water through a garden hose can be stopped by stepping on it and compressing it against concrete. The pubourethral ligaments also contribute to midurethral support.

Normal micturition cycle

Pathophysiology of urinary incontinence

Anal Incontinence

Definition

Faecal incontinence is defined as ‘the involuntary or inappropriate passage of faeces’ (Royal College of Physicians 1995). This definition, however, is incomplete as it may not include incontinence to flatus. Therefore, many adopt the term ‘anal incontinence’ to include flatus. Furthermore, this definition includes transient episodes of incontinence that may be experienced following a bout of gastrointestinal upset, and therefore a definition similar to that proposed by the International Continence Society for urinary incontinence may be more appropriate; namely, anal incontinence is the involuntary loss of flatus or faeces that is a social or hygienic problem.

Prevalence of anal incontinence

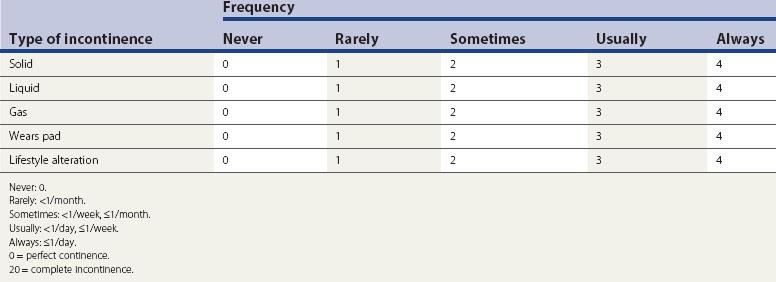

The estimated community prevalence of faecal incontinence is 4.2 per 1000 in men aged 15–64 years, 10.9 per 1000 in men aged 65 years or over, 1.7 per 1000 in women aged 15–64 years and 13.3 per 1000 in women aged 65 years or over. In residential homes for the elderly, the incidence was found to be 10.3% but may approach 60% in the elderly. Although the incidence of faecal incontinence in 45-year-old women is eight times higher than that in men of the same age, its prevalence has not been accurately assessed in the younger age groups. Even a minor degree of faecal incontinence can be very distressing and is a cause of great embarrassment; therefore, very few admit to it and seek medical assistance. In one study, half the patients referred to a gastrointestinal clinic complaining of diarrhoea were incontinent, but less than half of them volunteered this information. Moreover, clinicians may not enquire or document this symptom, and therefore the true prevalence of faecal incontinence can be grossly underestimated. A validated scoring system would therefore be more representative for epidemiological and research purposes. The Wexner scoring system is very popular and includes the need to wear a pad and alteration in lifestyle (Table 50.1). A modified version of the Wexner score has also been introduced to include faecal urgency, the ability to defer defaecation and the use of antidiarrhoeal medications.

The anal sphincter mechanism

The puborectalis and the external anal sphincter

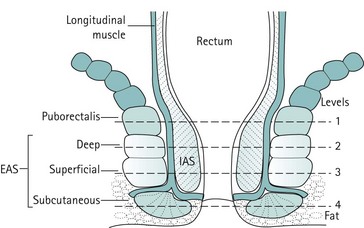

Proximally, the EAS lies in contiguity with the posterior half of the puborectalis; distally, it merges with the perianal skin. Like the levator ani, it is primarily composed of striated muscle. There is lack of consistency in the literature with regard to the structural subdivisions of the EAS. Some authors describe it as one structure, while others have subdivided it into two or even three components: the subcutaneous and deep EAS as annular muscles not attached to the coccyx, and the superficial EAS (middle layer) as being elliptical with fibres running anteroposteriorly from the perineal body to the coccyx and the anococcygeal raphe (Figure 50.6). The deep EAS has anterior fibres which cross over to the opposite side and combine with the superficial transverse perinei attaching to the ascending ramus of the ischium. Electrophysiological techniques have shown that the motor supply of the puborectalis is via direct branches of the sacral nerves (S3 and S4), and that of the EAS is via the pudendal nerve (S2–4). This supports the contention that the puborectalis is part of the levator ani and separate from the anal sphincter. Nevertheless, close cohesion between these muscles would seem to be essential because without it, peristalsis would pull the rectum upwards and over its contents without expelling them through the anus. Frustration in attempts to identify these subdivisions of the EAS led some authors to propose that the EAS is, in fact, a single structure with no real subdivision. As these subdivisions are not identified during surgery, they do not appear to be clinically relevant. However, a clear understanding of normal anatomy and variants is important during imaging (ultrasound and MRI) of the anal sphincter in order to avoid misinterpretation.

The defaecation cycle

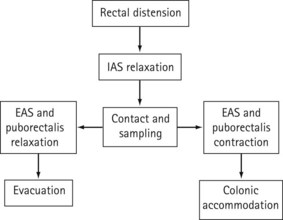

Following rectal distension with either faeces or flatus, the internal sphincter relaxes to allow sampling of rectal contents to take place by the specialized sensory epithelium of the anal canal (Figure 50.7). This relaxation is mediated via myenteric connections modulated by the autonomic nervous system, and is known as the ‘rectoanal inhibitory reflex’ (RAIR). If it is socially convenient, the puborectalis and external sphincter relax and evacuation occurs. If the time for evacuation is inappropriate, EAS contraction extends the period of continence to allow the compliance mechanisms within the colon to make adjustments in order to accommodate the increased rectal volume. Thereafter, the stretch receptors are no longer activated and afferent stimuli are abolished, together with the sensation of faecal urgency.

Figure 50.7 The mechanism of defaecation. EAS, external anal sphincter; IAS, internal anal sphincter.

The factors contributing to the mechanism of incontinence will be discussed in detail below.

Anal continence mechanisms

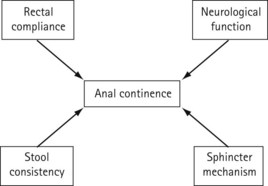

The mechanism that maintains continence is complex and affected by various factors such as mental function, lack of a compliant rectal reservoir, changes in stool consistency and volume, diminished anorectal sensation and enhanced colonic transit (Figure 50.8). However, analogous to urinary continence, anal continence can be maintained provided that the anal pressure exceeds the rectal pressure. As shown in Figure 50.6, the ultimate barrier to rectal contents is provided by the puborectalis sling and anal sphincters. An increased volume of liquid stool coupled with rapid colonic transit may overwhelm the compliant rectal reservoir. Therefore, if the rectum is able to function effectively as a rectal reservoir and in the presence of normal stool consistency, faecal incontinence can usually be attributed to defective function of the anal sphincter complex.

Comparison between Bladder and Bowel

Reflex adaptation of the rectum and bladder in response to filling are fairly analogous. There is an inverse relationship between distension and compliance. The ‘irritable bladder’ is more often found in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. The aetiology of faecal and urinary incontinence may also be comparable, and Table 50.2 compares bladder and bowel conditions.

| Bladder | Bowel |

|---|---|

| Detrusor overactivity | Irritable bowel syndrome |

| Urodynamic stress incontinence | Faecal incontinence |

| Detrusor sphincter dyssynergia | Anismus |

| Urgency | Urgency |

| Hypotonic bladder | Constipation |

Conclusion

KEY POINTS

Royal College of Physicians. Clinical Audit Scheme for the Management of Urinary and Faecal Incontinence. London: RCP; 1995. (out of print; ISBN 9781860160530)

Abrams P, Blaivas J, Stanton SL, Anderson J. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function. International Urogynaecology Journal. 1990;1:45-58.

Asmussen M, Ulmsten U. On the physiology of continence and pathophysiology of stress incontinence in the female. In: Umsten U, editor. Contributions to Gynaecology and Obstetrics. Volume 10, Female Stress Incontinence. Basel: Karger; 1983:32-50.

Bradley WE, Timm TW, Scott FB. Innervation of the detrusor muscle and urethra. Urological Clinics of North America. 1974;1:3-27.

Constantinou CE. Resting and stress urethral pressures as a clinical guide to the mechanism of continence. Clinics in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1985;12:343-356.

Coolsaet B. Cystometry. In: Stanton SL, editor. Clinical Gynaecological Urology. St Louis: CV Mosby; 1984:59-81.

DeLancey JO. Structural aspects of the extrinsic continence mechanism. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1988;72:296-301.

Gosling JA, Dixon J, Critchley HOD, Thompson SA. A comparative study of human external sphincter and periurethral levator ani muscle. British Journal of Urology. 1981;53:35-41.

Griffiths DJ. Urodynamics. Bristol: Adam Hilger; 1980.

Hilton P. Mechanism of continence. In: Stanton SL, Monga AK, editors. Clinical Urogynaecology. Churchill Livingstone; 2000:31-40.

Kapoor D, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Combined urinary and fecal incontinence. International Urogynaecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2005;16:321-328.

Monga AK, Phillips C. Structural urogynaecology. In: Thomas E, Stones RW, editors. Gynaecology Highlights. Oxford: Health Press; 1999:43-52.

Wein A. Physiology of micturition. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 1986;2:689-699.

Zacharin RF. The suspension mechanism of the female urethra. Journal of Anatomy. 1963;97:423-427.

Matzel KE. Sacral nerve stimulation for fecal disorders: evolution, current status, and future directions. Acta Neurochirurgica Supplement. 2007;97:351-357.

Pemberton JH, Swash M Henry MM, editors. The Pelvic Floor — its Function and Disorders. London: WB Saunders, 2002.

Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI. Anal sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. USA Journal of Medicine. 1993;329:1905-1911.

Sultan AH, Nugent K. Pathophysiology and non-surgical treatment of anal incontinence. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2004;111(Suppl 1):84-90.

Sultan AH, Thakar R, Fenner D. Perineal and Anal Sphincter Trauma. London: Springer; 2007.