Chapter 16 The Management Options for Adult Distal Humeral Fractures

Introduction

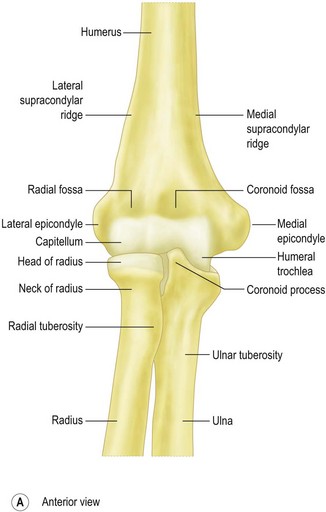

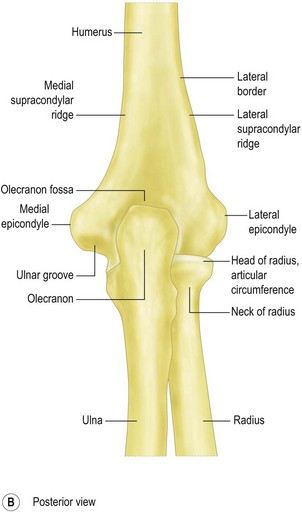

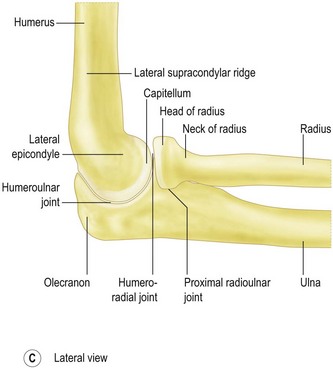

The humerus flattens and widens distally, with the maximum width between the epicondyles. The distal articular segment is held by the medial and lateral columns of thick cortical bone. A thin plate of bone between the columns constitutes the olecranon fossa posteriorly and the coronoid fossa anteriorly. This accommodates the olecranon and coronoid processes on extension and flexion respectively. The medial column diverges from the humerus at an angle of 45° and the proximal two-thirds are made of thick cortical bone, but the distal part is composed of soft cancellous bone. The triangular shape of the medial column enables screw placement for fracture fixation. The lateral column diverges from the humeral shaft at about 20° and has cortical bone similar to the medial column and also allows good fixation for screws. The distal part of this column is complex, with soft cancellous bone. The capitellum forms part of the lateral column.1,2 It has a curved anterior articular surface that articulates with the radial head. Posteriorly the surface is non-articular and therefore can be used for screw placement, although care should be taken not to penetrate the articular surface (Fig. 16.1A, B). The common extensor origin from the lateral column and the flexor origin from the medial column are responsible for fracture fragment rotation following injury.

Figure 16.1 The anatomy of the distal humerus.

From Ross LM, Lamperti ED, consulting eds. Thieme atlas of anatomy. Georg Thieme: Stuttgart; 2006.

The articular portion projects anterior to the shaft of the humerus at about 40° in the sagittal plane; hence it is not well exposed through a posterior approach (Fig. 16.1C). It also has a valgus angulation of 4–8° to the shaft in the coronal plane.3 Restoring the articular anatomy and stabilizing the two columns without impingement of the fossae by metalwork is the key to successful surgical management of these complex injuries.4

Background/aetiology

Distal humeral fractures have a bimodal age distribution, affecting the young (high energy) or the elderly (low energy). Peaks of incidence have been noted in males aged 12–19 years and in females aged 80 and older. The most common mechanism of injury is axial loading of the distal humerus, by a simple fall. The next most common causes of fractures are road traffic accidents and sport.5

Fractures of the distal humerus account for approximately 2–6% of all fractures and about 30% of all elbow fractures.6 One epidemiological study from Finland showed that the age-adjusted incidence of osteoporotic fractures of the distal humerus increased, from 12/100 000 women in 1970 to 28/100 000 women in 1995 and it predicts a threefold increase by the year 2030.7

Classification

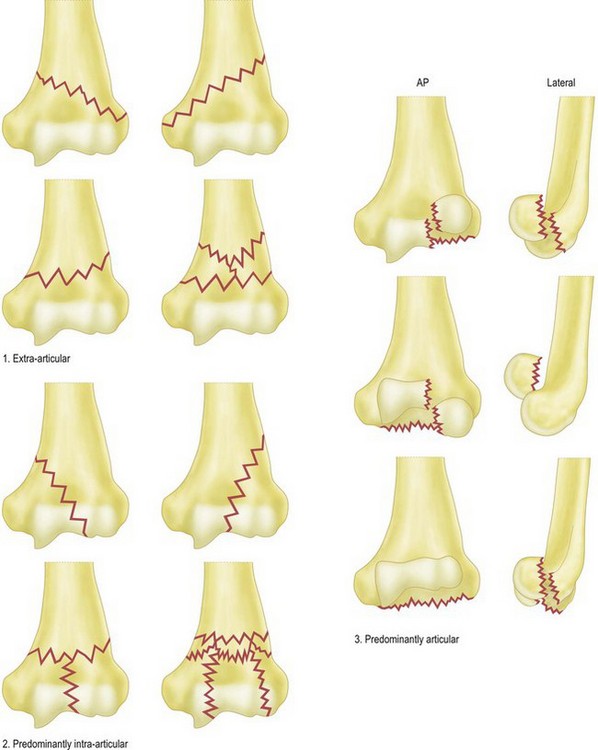

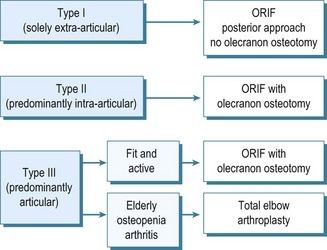

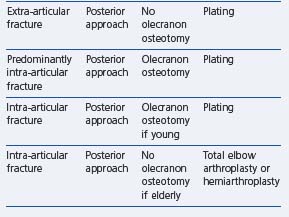

Various classification systems have been proposed for distal humeral fractures. In 1969 Riseborough and Radin developed a system of classifying T-shaped intercondylar fractures of the distal humerus based on the degree of fragment displacement, rotation and comminution.8 The AO group devised a classification system dividing the distal humerus into three types based on fracture lines lying extra-articularly, intra-articularly with or without involvement of a single column, and intra-articularly involving both columns. Stepwise progression into grouping and subgrouping of these fractures is dependent on the site of the fracture lines and the degree of fracture comminution. Fractures that do not fall into any of the three types or nine groups are labelled type D or .4, respectively.9 Later, Mehne and Jupiter developed a classification system based on three broad groups of fractures. Intra-articular fractures are subdivided into those with either single-columnar or bicolumnar involvement or those involving the capitellum or trochlea. Extra-articular, but intracapsular, fractures are also subdivided depending on the proximity of the fracture to the joint. Epicondyle fractures represent extra-articular fractures in this classification.1 In an assessment of these classification systems, Wainwright et al concluded that they were neither reliable nor reproducible, and thus their usefulness in decision making and comparison of outcomes was questionable.10 More recently, a clinically useful classification for fractures of the distal humerus has been developed and validated.11 This classification system has three main components – extra-articular, predominantly intra-articular and predominantly articular (Fig. 16.2) – based on plain AP and lateral radiographs. The classification system was found to be both substantially reliable (k, 0.664) and reproducible (k, 0.732). It achieved superior inter-observer and intra-observer agreement compared with the other three classification systems, with a low proportion of unclassifiable fractures. A management algorithm used with this classification aids the surgical decision-making process for these complex fractures (Fig. 16.3).

Presentation and investigations

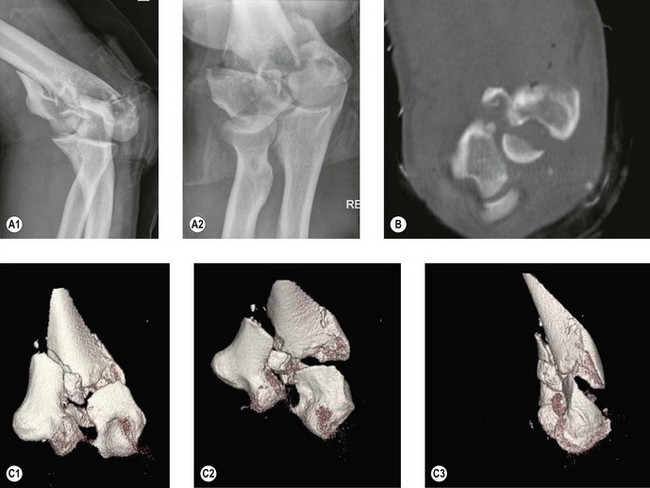

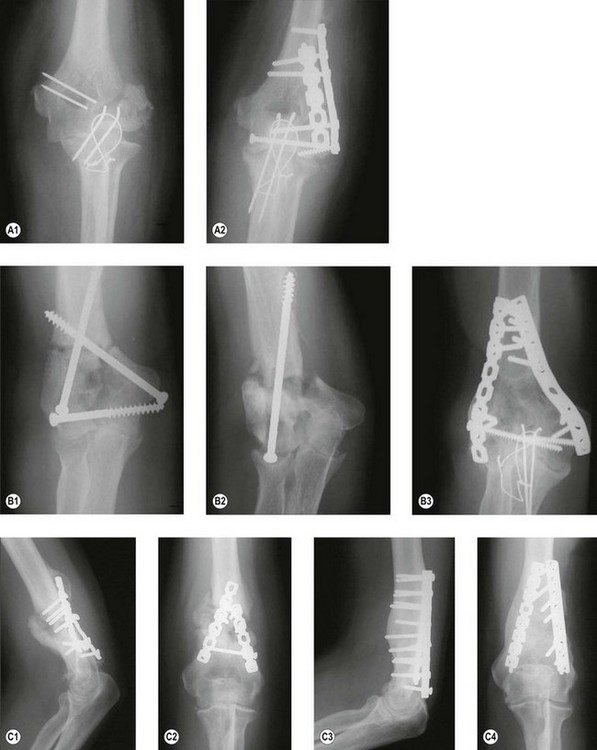

Once a clinical diagnosis has been established, plain anteroposterior and lateral radiographs should be performed to confirm the diagnosis (Fig. 16.4A). Further imaging with a CT scan may be helpful in assessing the type of fracture and the number and orientation of the fragments (Fig. 16.4B). More recently, three-dimensional reconstruction CT scanning has been used (Fig. 16.4C). Although these require more time and may increase the overall cost of imaging, they have been shown to be easier to interpret than two-dimensional scans and are helpful in identifying the components and special orientation of complex articular fragments. This can be particularly helpful for preoperative planning of complex fracture fixations.12

Surgical technique and rehabilitation

Clinical Pearl 16.2

With fractures extending proximally the radial nerve must also be found and protected.

If a preoperative decision is made that the fracture is not reconstructable, then either a hemiarthroplasty or total joint replacement should be considered. These options are described in Chapters 18 and 19.

Summary Box 16.1 Treatment options

| Elderly medically unfit patients | Conservative treatment |

|---|---|

| Young patients | Internal fixation – 90–90 plating or parallel plating |

| Elderly medically fit patients | Internal fixation, hemiarthroplasty or total elbow arthroplasty |

Treatment options, outcome and literature review

Extra-articular fractures

Fractures involving the distal diaphysis and metaphysis have been managed by non-operative and operative means.13,14 Advocates of non-operative treatment claim there are significant benefits of avoiding the risks associated with surgery, but comparative studies have shown better outcomes with surgical anatomical fixation and mobilization.13–15

Sarmiento et al reported good results from non-operative treatment by initially using a hanging cast, followed by functional bracing in comminuted extra-articular distal humeral fractures. They reported a 96% union rate and a residual varus angulation of 9° in 81% of patients. They noted minimal loss of range of movement and function.13 These results have not been reproduced in other institutes,15 and a recent comparative study of bracing and internal fixation concluded that anatomical reconstruction and internal fixation produced better outcomes.14 Non-operative treatment may occasionally be appropriate in patients who are anaesthetically unfit with multiple comorbidities.

When surgical intervention is undertaken, a rigid plate and screw fixation is recommended through a posterior triceps splitting/sparing approach (see Ch. 6 for surgical approach), taking care to protect the ulnar and radial nerves. The more distal extra-articular fractures are stabilized by reconstructing the medial and lateral columns using a double plating technique.

Predominantly intra-articular fractures

The goal of treatment in these fractures is to restore articular anatomy and provide stable fixation, enabling early motion. The complex anatomy, substantial forces across the elbow joint, and frequently diminished bone density make fixation technically demanding and explain the relatively high complication rates. The majority of non-unions (as high as 75%) in this region are caused by inadequate primary fracture fixations;6 hence stable initial fixation with early motion is the key to a good outcome.

Historically these fractures were treated non-operatively using the ‘bag of bones’ method or plaster immobilization with minimal fixation techniques.16 The outcomes, however, were poor compared to stable fixation17 and non-operative treatment is now only used for patients with multiple comorbidities who are unfit for surgery. The gold standard for management of these fractures is open reduction, rigid internal fixation and early mobilization.

The surgical approach requires good exposure of the articular fragments and the distal humeral shaft. This can be achieved adequately by an olecranon osteotomy18 (apex distal, chevron) at the level of the bare area of the olecranon with proximal reflection of the triceps. An olecranon osteotomy is particularly useful in complex articular injuries since it is often difficult to be certain that an accurate articular reconstruction has been achieved if the olecranon is left intact. Pre-drilling holes to fix the osteotomy prior to performing the osteotomy helps in anatomical reconstruction of the olecranon at the end of the procedure.

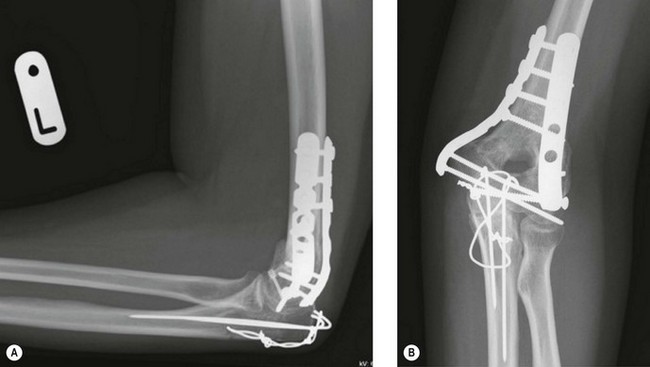

Careful isolation and protection of the ulnar nerve are needed during fracture exposure, owing to its close proximity to the medial epicondyle. The fracture haematoma is removed, taking care to avoid loss of small bone fragments. The fracture anatomy must be fully identified if the fracture is to be successfully reconstructed. It is important to begin the reconstruction by starting with fragments that clearly fit together. These may be held with temporary wires or fracture reduction clamps. Once adequate reduction of the fragments is achieved, definitive fixation using plates and screws can be performed. The plates may need to be contoured to the distal humerus or, alternatively, pre-contoured plates may be used. The pre-contoured plates have the advantage of providing a template onto which the fracture can be reduced. Most modern plating systems can be used in locking, non-locking or hybrid modes. The locking plates provide a fixed angle construct, which acts as a scaffold in supporting the osteopenic distal humerus. The plates are either placed in a 90–90 (posterolateral and medial) (Fig. 16.5) or a parallel (medial and lateral) (Fig. 16.6) configuration to support the medial and lateral columns. The 90–90 configuration is the traditional AO method of fixing the distal humerus. The procedure involves fixation of the articular fragments, and then fixation of the articular segment to the humeral shaft with the two plates.

Biomechanical studies have shown locking plates to provide superior bone implant anchorage in osteoporotic (bone mineral density < 420 mg/cm3) and comminuted fractures of the distal humerus, but have shown no difference in good-quality bone when fractures were fixed with the 90–90 technique.19 In addition, superior stiffness to bending and torsion has been reported with parallel plating when compared to the 90–90 technique.20 Clinical studies have also shown superior results with parallel plating.21 The parallel plating technique is described in more detail in Chapter 17.

Articular fractures

Internal fixation

Intra-articular fractures of the distal humerus in young and active individuals should be managed by internal fixation. Good-quality imaging helps identify the various fracture patterns, and this is essential for preoperative planning. Various patterns of injury of the distal humerus have been described. Ring et al produced a descriptive classification based on the configuration of the fracture and described five components of the distal humerus: (1) the capitellum and the lateral aspect of the trochlea; (2) the lateral epicondyle; (3) the posterior aspect of the lateral column; (4) the posterior aspect of the trochlea; and (5) the medial epicondyle.22 The surgical approach to these fractures is dependent on the type of fracture.

Isolated capitellar fractures are rare. Bryan and Morrey described three types of capitellar fractures: type 1 is a shear type of fracture in the coronal plane involving most of the capitellum, with little or no trochlear element but with good subchondral bone; type 2 is a capitellar fracture with a thin shell of subchondral bone; and type 3 is a comminuted or compression fracture of the capitellum.23 This classification does not address capitellar fractures that extend into the trochlea. A more recent classification proposed by Dubberley et al is more useful in managing these injuries. This classification has three types: type 1 is primarily a capitellar fracture, which is approached through Kocher’s approach; type 2 fractures involve the capitellum and the trochlea as one fragment; these fractures are best exposed through combined lateral and medial incisions or via an olecranon osteotomy; in type 3, the capitellar and trochlear fragments are separate and these are comminuted shear fractures. An olecranon osteotomy is the preferred approach for these fractures (Fig. 16.7). When posterior wall comminution is recognized in any of the fractures, it is further subclassified as a type B injury.24 If the capitellum, lateral trochlea and the lateral epicondyle are involved, then a lateral approach with distal reflection of the lateral epicondyle with its soft tissue attachment provides adequate exposure of the fracture fragments and facilitates fixation using headless cannulated screws after temporary wire fixation. The lateral epicondylar fragment is then reattached using a screw or tension band wiring technique. If the medial epicondyle is fractured with a small medial articular fragment a medial approach to the elbow can be used. The olecranon and radial head can be used as a template to reduce the fracture, taking care to elevate any posterior impaction.

Various internal fixation devices have been used to fix intra-articular fractures. Biomechanical studies have shown that posteroanteriorly directed cancellous lag screws are significantly more stable than anteroposteriorly directed screws, but the conical headless screw (Acutrak) was significantly more stable than posteroanterior cancellous screws.25 Comparison between the types of headless screws showed the Acutrak screws to be superior to Herbert screws.26 In the presence of comminution, supplemental bone graft and/or plate fixation should be considered.24

Ring et al reported good to excellent results in 16 of 21 patients who had open reduction and internal fixation of articular fractures of the distal humerus at a mean follow-up of 40 months. The average arc of movement at the ulnohumeral joint was 96°. Ten patients required a second operation (six had contracture release, two for ulnar nerve decompressions, one needed revision fixation and one had removal of metalwork).22 More recently, Dubberley et al reported functional outcomes in 28 patients with a mean follow-up of 56 months. The average Mayo performance index was 91±11, with a mean range of motion of 19–138°. Two patients with comminution had non-union requiring total elbow arthroplasty.24

Total elbow replacement

Although anatomical reduction and fracture fixation is the treatment of choice for distal humeral fractures, the presence of comminution and osteopenia makes this a demanding and difficult procedure in the older patient. For this reason total elbow arthroplasty has been advocated as an alternative surgical option.27 It is indicated in elderly patients with low demands, patients of any age with inflammatory arthritis, pathological bone or reduced life expectancy, or in patients with non-unions who are over the age of 70. Good to excellent medium-term results with linked prosthesis have been reported in rheumatoid and non-rheumatoid patients.28,29 A retrospective review of 48 patients treated primarily by a total elbow arthroplasty for distal humeral fractures reported an average Mayo elbow performance score of 93 (maximum possible 100) at a mean follow-up of 7 years. Rheumatoid arthritis was present in 40% of the patients.28 A recent study of 26 non-rheumatoid patients who had linked total elbow replacement for distal humerus fractures reported a mean Mayo elbow performance score of 92 at 63 months follow-up.29 Unlinked total elbow replacements have also been used for distal humeral fractures, and although early results are promising no long-term results are available.30

A prospective randomized multicentre trial comparing open reduction and internal fixation and primary semi-constrained total elbow replacement for comminuted intra-articular fractures in patients over the age of 65 reported better outcomes after a total elbow replacement at 2 years compared to open reduction and internal fixation.31 A study comparing total elbow arthroplasty undertaken as a primary procedure for distal humeral fractures in the elderly, with total elbow arthroplasty after failed internal fixation or conservative treatment at a mean follow-up of 56.1 months, reported no significant difference between the two groups.32 The place of total elbow arthroplasty for distal humeral fractures is dealt with in greater detail in Chapter 19.

Complications of treatment

The management of postoperative stiffness is dealt with in Chapter 20.

Malunion and non-union of distal humeral fractures can be particularly challenging to treat. They will usually require further surgery, with debridement of non-united bone fragments, bone grafting and replating. Ali et al33 reported their experience of treating 16 patients with distal humeral non-unions. They noted that although non-unions occurred in all decades from the second to the ninth they were most common in patients aged between 41 and 50 years (31%). They found no association with gender, a history of smoking or mechanism of injury. When, however, they analysed other publications,34,35 including the AO classification of the original fracture, they noted that non-unions were more frequently associated with fractures that had a supracondylar component. They also stated that they considered the primary treatment of the original fracture to be suboptimal in 12 of their 16 patients (75%). Fractures had been fixed using only K-wires, screws or inadequate plates (Fig. 16.8).

1 Mehne DK, Jupiter JB. Fractures of the distal humerus. In: Browner BD, Jupiter JB, Levine AM, et al, editors. Skeletal trauma: fractures, dislocations, ligamentous injuries. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1992:1146-1176.

2 Diederichs G, Issever A, Greiner S, et al. Three-dimensional distribution of trabecular bone density and cortical thickness in the distal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:399-407.

3 London JT. Kinematics of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:529-535.

4 O’Driscoll SW. Optimizing stability in distal humeral fracture fixation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:186S-194S.

5 Robinson CM, Hill RM, Jacobs N, et al. Adult distal humeral metaphyseal fractures: epidemiology and results of treatment. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17(1):38-47.

6 Korner J, Lill H, Müller LP, et al. The LCP-concept in the operative treatment of distal humerus fractures: biological, biomechanical and surgical aspects. Injury. 2003;34(Suppl 2):20-30.

7 Palvanen M, Kannus P, Niemi S, et al. Secular trends in the osteoporotic fractures of the distal humerus. Eur J Epidemiol. 1998;14:159-164.

8 Riseborough EJ, Radin EL. Intercondylar T fractures of the distal humerus in the adult: a comparison of operative and non-operative treatment in 29 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:130-141.

9 Muller ME, Nazarian S, Koch P, et al. The comprehensive classification of fractures in long bones. Berlin: Springer; 1990.

10 Wainwright AM, Williams JR, Carr AJ. Interobserver and intraobserver variation in classification systems for fractures of the distal humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:625-626.

11 Davies MB, Stanley D. A clinically applicable fracture classification for distal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(5):602-608.

12 Doornberg J, Lindenhovius A, Kloen P, et al. Two and three-dimensional computed tomography for the classification and management of distal humeral fractures. evaluation of reliability and diagnostic accuracy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1795-1801.

13 Sarmiento A, Horowitz A, Aboulafia A, et al. Functional bracing for comminuted extra-articular fractures of the distal third of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72-B:283-287.

14 Jawa A, McCarty P, Doornberg J, et al. Extra-articular distal-third diaphyseal fractures of the humerus: a comparison of functional bracing and plate fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2343-2347.

15 Aitken GK, Rorabeck CH. Distal humeral fractures in the adult. Clin Orthop. 1986;207:191-197.

16 Ring D, Jupiter JB. Complex fractures of the distal humerus and their complications. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:85-97.

17 Papaioannou N, Babis GCh, Kalavritinos J, et al. Operative treatment of type C intra-articular fractures of the distal humerus: the role of stability achieved at surgery on final outcome. Injury. 1995;26(3):169-173.

18 Wilkinson JM, Stanley D. Posterior surgical approaches to the elbow: a comparative anatomic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(4):380-382.

19 Schuster I, Korner J, Arzdorf M, et al. Mechanical comparison in cadaver specimens of three different 90-degree double-plate osteosyntheses for simulated C2-type distal humerus fractures with varying bone densities. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22(2):113-120.

20 Schemitsch EH, Tencer AF, Henley MB. Biomechanical evaluation of methods of internal fixation of the distal humerus. J Orthop Trauma. 1994;8:468-475.

21 Shin SJ, Sohn HS, Do NM. A clinical comparison of two different double plating methods for intraarticular distal humerus fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:2-9.

22 Ring D, Jupiter JB, Gulotta L. Articular fractures of the distal part of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:232-238.

23 Bryan RS, Morrey BF. Fractures of the distal humerus. In: Morrey BF, editor. The elbow and its disorders. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1985:302-339.

24 Dubberley JH, Faber KJ, MacDermid JC, et al. Outcome after open reduction and internal fixation of capitellar and trochlear fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(1):46-54.

25 Elkowitz SJ, Polatsch DB, Egol KA, et al. Capitellum fractures: a biomechanical evaluation of three fixation methods. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(7):503-506.

26 Elkowitz SJ, Kubiak EN, Polatsch D, et al. Comparison of two headless screw designs for fixation of capitellum fractures. Bull Hosp Joint Dis. 2003;61(3–4):123-126.

27 Bryan RS, Morrey BF. Fractures of the distal humerus. In: Morrey BF, editor. The elbow and its disorders. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1985:325-333.

28 Kamineni S, Morrey BF. Distal humeral fractures treated with noncustom total elbow replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:940-947.

29 Ali A, Shahane S, Stanley D. Total elbow arthroplasty for distal humeral fractures: indications, surgical approach, technical tips, and outcome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):53-58.

30 Kalogrianitis S, Sinopidis C, El Meligy M, et al. Unlinked elbow arthroplasty as primary treatment for fractures of the distal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:287-292.

31 McKee MD. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial of open reduction – internal fixation versus total elbow arthroplasty for displaced intra-articular distal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:3-12.

32 Prasad N, Dent C. Outcome of total elbow replacement for distal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:343-348.

33 Ali A, Douglas H, Stanley D. Revision surgery for non-union after early failure of fixation of fractures of the distal humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87B:1107-1110.

34 Ackerman G, Jupiter JB. Non-union of fractures of the distal end of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70A:75-83.

35 Sanders RA, Sackett JR. Open reduction and internal fixation of delayed union and non-union of the distal humerus. J Orthop Trauma. 1990;4:254-259.