Chapter 2 The Long Case

Most candidates have a small leather briefcase (or equivalent carrying bag) for their equipment. Be absolutely familiar with the equipment you have in your bag. Nothing looks worse than a candidate fumbling through his or her bag or, worse still, his or her pockets at the vital moment.

Obtaining the history

Making notes is vital. Two commonly used methods are:

1. Using a small spiral-bound pad.

2. Using a small card system: numbering the cards, and using headings such as ‘examination findings’.

Remember to keep to the essentials and to include the following:

1. Identification of the child’s details—age, date of birth, home address.

2. Identification of the clinical problem(s).

3. Specific inquiry of system involvement.

4. Relevant past medical history: include birth history, immunisation history.

7. Social history: always ask about parental relationships, number of children, family income, financial support, other siblings’ reactions to the patient’s illness, schooling.

The following questions have been found useful by many candidates:

1. What exactly is wrong with your child?

2. Is your child an inpatient at the moment?

3. What are the names of the doctors taking care of your child?

4. What tests have been done on your child? Have any new tests been done lately? How often do you come for review? How many times has your child been admitted?

5. What treatment is your child on? Have there been any recent changes in your child’s treatment?

6. What is worrying you the most?

7. What is worrying the doctors the most?

8. What is worrying the child the most?

9. What complications of treatment are there?

10. What of the future? For the family? For the patient?

11. Is there anything else that someone else has done or asked that I haven’t done or asked?

Remember, do not accept the patient’s history without questioning.

Preparation to meet the examiners

Ask yourself whether the case is mainly a management or a diagnostic problem. If it is a diagnostic problem, remember that ‘common things occur commonly’. If more than half of your findings support your first diagnosis, then it is most likely the correct one. For your alternative diagnoses, take the main positive findings and have three possible diagnoses for each. Make a summary of the possible diagnoses that occur three or more times.

1. ‘Tell me about your patient’. You should be able to give a clear, concise presentation lasting less than 10–12 minutes.

2. ‘What is your conclusion about this case?’ You should respond by giving a most likely diagnosis and differential diagnoses. Avoid giving an over-comprehensive list of differential diagnoses.

3. ‘How would you manage this patient?’ You should prepare an outline of management and be able to support it. You are probably going to be asked about relevant investigations. You should have reasons for doing the test and be able to discuss the test in detail. Write down any test results given and comment on their significance.

A long-case proforma

Details and history

Next, the presenting complaint is set out in detail.

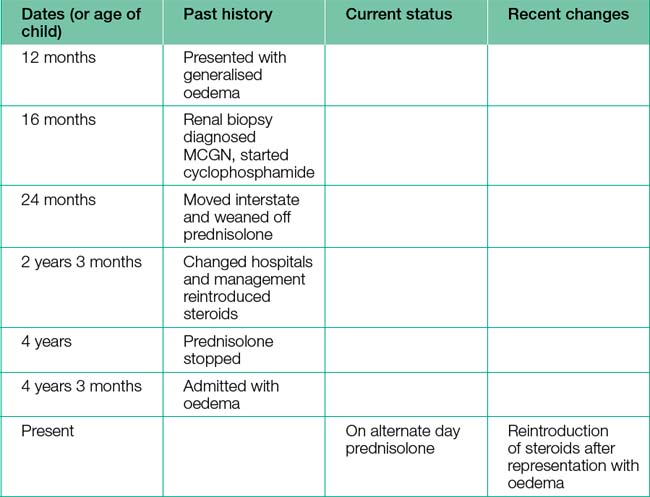

Then, for each problem listed in the opening statement, make four columns, with the headings Dates (or age of child), Past history, Current status, Recent changes. The history is listed in chronological order under each heading. For example, if the problem was nephrotic syndrome it could be listed as in Table 2.1.

Remaining history

When you have completed the problem listing sheets, remember to ask the parent supplying the history, ‘What did the examiners ask you?’ Then the rest of the history can be obtained. The prompts given in Table 2.2 may help.

| Birth history |

| Date of birth__________/Birth weight__________/Hospital__________Pregnancy: Drugs__________/Bleeding__________/Illnesses__________Hyper/hypotension__________/Hospitalisations__________Ultrasounds__________/Other tests__________Polyhydramnios:__________/Fetal movements:__________Planned?__________/Gestation__________/Delivery method__________Apgar scores__________at 1 minute __________at 5 minutes |

| Perinatal history |

| Respiratory distress__________/Oxygen requirement__________Feeding: Breast__________/Bottle__________/Tube__________Jaundice__________/Weight gain__________/Other problems__________Discharge date/age__________/Discharge weight__________ |

| Feeding history |

| Currently__________/Breast/bottle: until__________/Solids: since__________Past feeding history__________ |

| Milestones |

| Good baby?__________/Hearing__________/Smiled__________Compared to sibs__________/Sat__________/Sleeping behaviour__________Crawled__________/Feeding self__________/Walking__________Toilet trained__________/Talking: single words__________Sentences__________School compared to sibs__________/Vision__________Current developmental abilities/problems:Vision__________/Hearing__________/Gross motor__________Fine motor__________/Language__________/Personal social__________ |

| Family history |

| Mother: Name__________Age__________ Job__________ Health__________Father: Name__________Age__________ Job__________ Health__________Note any consanguinity__________/Planning any more children?__________Relevant family history__________/Other diseases in family__________Previous marriages__________Past pregnancies: Terminations__________/Miscarriages__________Children who have died__________Family interactions__________/Family supports__________Family’s understanding of disease: Mother/Father/Sibs__________ |

| Social history (can be the most important) |

| Financial status__________/Private health insurance__________Home__________/Car__________/Allowances__________Family supports__________/Other supports__________Societies__________/Magazines__________How long in Australia?__________ |

| School history |

| School attended__________/Grade__________/Performance__________Subjects__________/Sports__________/Friends__________Ambitions__________/How much school has been missed?__________Repeated any grades?__________ |

| Parents |

| Change in social life__________/Parents’ friends__________Last holiday?__________/Respite care? __________ |

| Home |

| Any structural changes to cope with the illness?__________ |

| Transport to school/doctor |

| Need for special transport__________/Financial burden of transport__________ |

| Other past history |

| Infections__________/Fractures__________Operations__________/Hospitalisations__________ |

| Immunisation |

| Up to date?__________/Given on time?__________Any missed?__________/Adverse reactions?__________ |

| Allergies |

| Presenting symptoms: Rash__________/Angio-oedema__________/Anaphylaxis__________ Requirement for adrenaline?__________/Medicalert bracelet__________ |

| Most serious problem |

| Mother’s opinion__________/Father’s opinion__________Patient’s opinion__________/Doctor’s opinion__________ |

| Parents’ understanding of disease |

| _________ |

| Compliance |

| _________ |

| Alternative medicine |

| __________ |

| Systems review |

| Cardiovascular/Respiratory/Ear, nose, throat/Eyes/Gastrointestinal tract/Central nervous system/Skin/Joints/Endocrine/Renal/Haematological |

| Home management |

| Medications Side effects Levels Note: List the above under headings: many long-case patients are on multiple drugs. |

| Other management |

| Physiotherapy__________/Occupational therapy__________Speech therapy __________/Other therapy__________Daily routine__________Clinics attended__________Specialists seen regularly (what do they ask/do/examine?)__________Local doctor__________Paediatrician __________ |

Examination

Next, describe the parameters (head circumference, weight, height) and show the examiners the centile chart (which you have of course plotted at high speed). The vital signs (pulse, respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature and, if relevant to the presentation, urinalysis) may then be given, and then the findings in the organ system most relevant to the child’s current clinical problems. Again, using the nephrotic syndrome example, this would be similar to the following: ‘Examination of the renal system was as follows: periorbital oedema, ascites, tense scrotum, no effusions, Cushingoid features (buffalo hump, loss of supraclavicular fossa), but no striae, cataracts, not short, no acne, no bone pain, no bruising’.

• ‘As regards management, my main concerns are …’, or

• ‘With respect to [problem], as the paediatrician looking after [patient], I would …’, or

Remember to have a list of issues ready to discuss confidently.