Chapter 5 The long case

Purpose

Format

There is only one long case. You may take in your exami nation kit but not any written material. Notes are to be written on paper provided. You have 35 min utes with the patient to spend however you choose, followed by five minutes sitting outside the exam room to organise/consolidate/prepare your thoughts and written notes, followed by 20 minutes with two examiners for your presentation and questioning. During your time with the examiners, one examiner will direct the questions while the other mostly observes and takes notes. The second examiner may occasionally ask questions to clarify issues, but typically remains silent. This pattern will continue for all the clinical components of the examination and is designed to ensure fairness and consistency. While one examiner is leading the discussion, the other is checking that you have addressed the relevant material. Both examiners agree on the final mark using these notes. Should you be unsuccessful in the examination overall, these notes will be used to provide you with feedback.

The presentation

At the end of your presentation, the examiners may clarify some points or, unless you beat them to it, they will typically begin with the actual or potential ED presentations that could be expected with this patient. You may be shown results of investigations or other material from the patient’s clinical notes as part of the discussion. All questions will relate specifically to this patient and thus will vary from you being asked about a provisional diagnosis, a diff erential diagnosis and/or an investigation plan, right through to detailed management.

Preparation

General preparation for this section of the exam is relatively easy as it covers very much what you do every day. Therefore, the best preparation is to remem ber the core principles (see Chapter 1) and use them constantly: all are relevant for the long case.

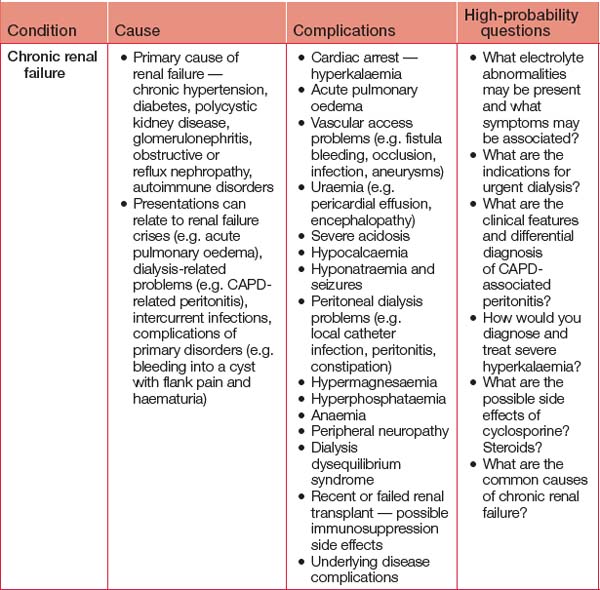

Table 5.1 outlines important cases to review, although this is by no means an exhaustive list of what you can expect to encounter in the exam. Look out for patients with these conditions at work during your exam preparations. It is always beneficial to have seen actual patients who can literally be ‘walking textbooks’. Recalling your management of actual cases is easier than trying to remember lists from texts.

Considering how the 3Cs apply to each potential long case problem will enable you to pre-empt and prepare for the obvious relevant questions you could be asked in the exam. Some examples of this approach are provided in Table 5.2.

On the day

Time with the patient (35 minutes)

You may be provided with the patient’s medication chart (if an in-patient) or the patient may have a list. If not, compile a list as best you can — as you would during a clinical shift in ED. Some observations may be provided where pertinent, but none should be expected or demanded. If you want a blood pressure and it is not provided, measure it. If fundal exami nation is relevant to the case (e.g. diabetic, stroke, visual field defect), you will be provided with an ophthalmoscope. However, potentially embarrassing examinations such as PR or PV examinations are not to be undertaken. You will have time with the examiners to say what other aspects would make part of your normal examination. Where relevant, these findings will be provided by the examiners.

For outpatients, start with their previous presentations, remembering one of these may be the starting point of discussions with the examiners.

History taking and examination

It is worthwhile spending a minute at the start of your allocated time setting out your paper in the way you have practised, as this will help prevent omissions. An example of some section headings to consider is provided in Table 5.3. Modification is needed for diff erent types of patients (e.g. a birth, developmental and immunisation history will be most relevant for children).

TABLE 5.3 Possible subheadings for the long case presentation

* Developing a mnemonic for the various systems is a good way to ensure all systems are covered.

Aim to finish your history and examination with time to spare before your 35 minutes are up. Make sure you ask the patient whether there was anything the examiners seemed particularly interested in or any aspect of the history or examination they elicited that you have not. Having spare time will enable you to explore more detail if needed, confirm any findings you were unsure about and commence the process of collating your thoughts. If you start this while you are still with the patient, you have the opportunity to complete any ‘gaps’ that may suddenly come to mind.

The five-minute break

At the end of the presentation, the examiners will ask you some questions. Initial questions will relate to ED presentations (actual or potential for this patient). Use this time to consider what those questions are likely to be, organise your thoughts and prepare your responses. You should also decide whether you wish to lead or be led in this ‘dance’ with the examiners.