The ligamentous concept

Introduction

Lesions of the posterior arch (posterior ligaments and facet joints) have long been considered an important source of low back pain. However, the classic work of Mixter and Barr in 1934, which focused attention on the disc, overshadowed the importance of posterior ligamentous lesions. Disc lesions must be considered to be the main source of backache and sciatica but ligamentous problems remain a possible basis for lumbar symptoms. In lesions of the lumbar spine, discs take the strain first but it is obvious that any change in height and mechanical properties of the disc will also influence the posterior ligamentous structures. There is anatomical evidence for free nerve endings in the posterior ligaments and the capsule of the facet joint.1–3 In addition, a number of investigations have shown that low back pain can be produced by direct stimulation of facet joints and ligaments.4–6

Although ligamentous pain is difficult to prove by technical investigations, it is possible to identify it on clinical grounds.7–10 The ultimate proof of a posterior arch lesion is the improvement of pain and dysfunction after diagnostic infiltration with local anaesthesia.

The structures discussed in this chapter are the supra- and interspinous ligaments, the facet joints, and the intertransverse and the iliolumbar ligaments. The behaviour of the sacroiliac, sacrospinal and sacrotuberous ligaments shows some similarity to that of the lumbar ligaments; however, their disorders and treatment are detailed in Chapter 43.

Mechanism of ligamentous pain

Most of the stabilizing support for the lumbar spine in standing, sitting and flexion–extension is determined by the tension of the ligaments rather than the strength of the paravertebral muscles (Wyke11: Ch. 11; Stokes and Frymoyer12). Postural strain, therefore, will affect the nociceptors in the capsules of the facet joints and the ligaments of the posterior arch, which happens when prolonged or increased postural pressure falls on normal tissues, or when abnormal (traumatized, inflamed or deformed) ligaments are subjected to normal postural stress. The first – prolonged or increased static loading of normal and healthy ligamentous tissues – is the ‘postural’ syndrome. The second – symptoms arising from abnormal (degenerated or inflamed) tissues subjected to normal mechanical stress – is the ‘dysfunction’ syndrome.

Postural syndrome

Pathological changes in the structures responsible for the pain are not present. Only the maintenance of a stress on a normal tissue creates this type of pain – an example of what has been termed ‘the bent finger’ syndrome; if a finger is bent backwards, sooner or later pain will appear.9 If sufficient force is applied for long enough, mechanical deformation of the sensitive structures in the involved tissues induces pain. It is this lumbar aching that everyone experiences when a particular posture is maintained for a long period. Pain increases in intensity the longer the time spent in the position, but the moment another position is adopted the pain will gradually disappear (Box 34.1).

Dysfunction syndrome

Although, in the postural syndrome, the structures are normal and pain is initially produced by subjecting these structures to increased mechanical stresses, it is not unlikely that, sooner or later, damage to the tissues involved will follow. The ligaments can become elongated or inflamed, which results in pain of chemical origin and also in structural changes. In this new situation, pain will be provoked by stress on structures which have become pathological. It is this progression which produces the dysfunction syndrome, defined as lumbar pain resulting from normal mechanical stress on pathological ligaments (Box 34.2).

Postural syndrome

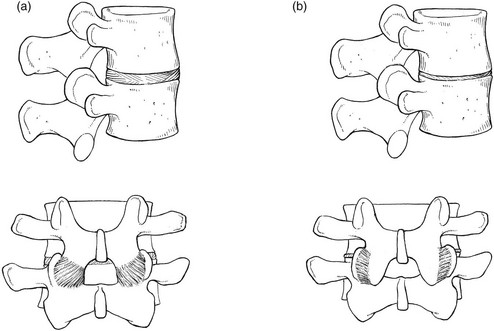

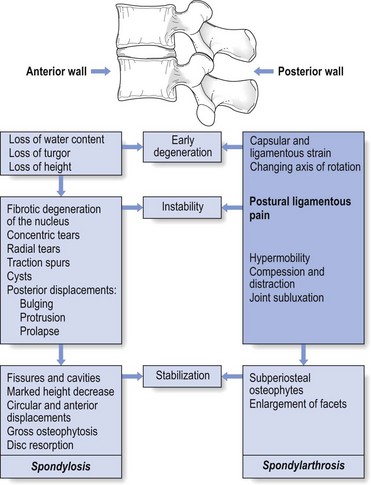

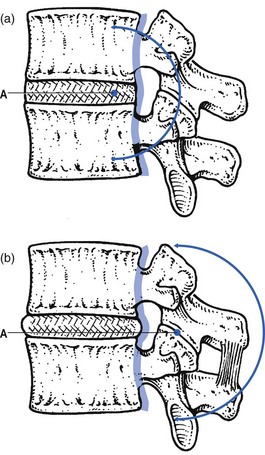

Postural pain appears when normal ligaments are subjected to abnormal mechanical stresses. This happens with inappropriate spinal loading – poor sitting or prolonged bent positions. Alternatively, abnormal mechanical stresses can originate when, as a result of decreasing intervertebral height, too great a load is applied posteriorly to the spine, a situation which can occur during a particular period in the ageing spine. The loss of turgor in the disc and the decrease in intervertebral space will first allow the posterior ligaments to become lax, causing some postural strain. Further diminution in disc height results in structural changes. At the posterior facets, the joint surfaces override and simulate hyperextension (Fig. 34.1). In this position, considerably more weight falls on the facet joints and the posterior capsule becomes overstretched. Two types of fibre orientation have been described in the capsular fibres of the facet joint.13 Type I capsules have the fibres running diagonally from lateral–caudal to medial– cranial; in type II, the direction is horizontal between the points of insertion on the lower and upper articular processes. Especially in type II, axial loading of the spine results in considerable stretching of the fibres as the upper articular process slides downwards over the lower. Pain may then result.

A similar mechanism probably also accounts for ligamentous pain following disc excision and could also explain back pain after chemonucleolysis, which causes a sudden decrease in disc height.14

Postural pain in the ageing spine

Continuing degeneration produces a stiff spine because of periarticular fibrosis and enlargement of the facets. As a result, postural pain normally disappears as these changes advance after middle age (see Fig. 34.3 below).

History

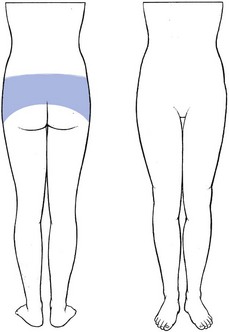

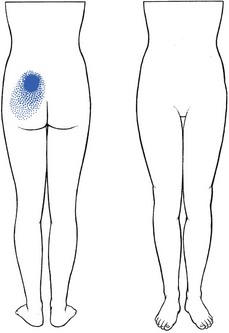

The patient is typically young and female, and has diffuse backache, with bilateral radiation over the iliac crests and the sacroiliac joints (Fig. 34.2); pain is never referred below the upper buttocks. When postural pain originates from the sacroiliac ligaments, however, pain reference in the S1 and S2 dermatomes can be encountered (see Ch. 43).

The ache usually starts after being in one position for a considerable length of time – sitting or standing – and the intensity of the pain and the duration of the position are related. Barbor8 described postural ligamentous pain as the ‘theatre, cocktail party’ syndrome, because these are characteristic examples of prolonged sitting or standing which produce low back pain. Lying down – for instance, prone – often leads to increased pain, and walking can be painful, especially if the patient is merely strolling slowly. In contrast and surprisingly, to someone who is not familiar with the syndrome, the patient states that during activity and sports he or she is absolutely pain-free. Postural pain (Fig. 34.3) is, as its name implies, a result of positions not movements.

Treatment

Classically, self-treatment and especially prophylaxis are recommended. The patient should be informed about the pain mechanism and taught how to avoid constant static postures. If prolonged sitting is unavoidable, attention should be directed to a proper posture and good choice of furniture. Standing should involve regular movement of the body weight from one leg to the other. All such information and training can be given during a ‘back school’ programme (see p. 588). Contrary to general belief,15 it is unnecessary to give patients with postural back pain a programme of strengthening exercises. Strong muscles will not prevent pain provoked by static mechanical stresses.

Chemical sclerosis was used to treat inguinal hernias between the wars and the resulting dense fibrosis of the tissues was noted by Hackett. He adapted the method for the ligamentous periosteal junctions of the posterior lumbar arch as a treatment for chronic low back pain,4 and others followed.16,17 The initial solution used was zinc sulphate and carbolic acid but a bewildering variety of other materials ensued, including various soap derivatives and psyllium seed oil. Not surprisingly, considerable side effects were experienced: three instances of paralysis18,19 and two deaths after injection into the subarachnoid space.20 Dextrose–phenol–glycerol solution, originally developed for the treatment of varicose veins, had a good safety record21 and was introduced into spinal use by Ongley in the late 1950s.10 The mixture provokes an effective inflammatory response, which leads to fibroblast proliferation and new collagen production (O. Troisier, cited by Cyriax22: p. 339). At the periosteal junctions of the ligaments, the fibrosis results in an increase in girth of the ligaments, with contraction and subsequent pain relief. As some of the phenol is injected at or around the medial and lateral branches of the posterior ramus, a direct effect on the nerves may also occur23 and could explain the rapid relief (sometimes from the day or days after the injections) in some patients.

In chronic postural backache, the results of these injections are fair. In our experience, about 70% of patients suffering from a postural syndrome become pain-free after 6–8 weeks – the time required to induce sufficient sclerosis. The experience of others is similar.24 Two randomized studies have shown the effectiveness of the treatment in a group of patients suffering from chronic postural low back pain for an average period of 10 years.10,25

Posterior dysfunction syndrome

The posterior structures involved are the facet joints, the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments, and the iliolumbar ligaments. Disordered muscles are a great rarity, easily distinguished because they are contractile. Ligamentous lesions of the sacroiliac joint will be discussed in Chapter 43.

Facet joints

Arthropathy of the facet joints has been regarded as an important source of low back pain for some time. In 1911, Goldthwait maintained that disease of the facet joint was the chief source of backache.26 By 1933, the term ‘facet joint syndrome’ had been introduced.27 In the 1960s and 1970s, the question as to whether back pain could arise from a facet joint problem was vigorously debated in the medical literature.28–30 Opponents of the idea use the following arguments: first, there is no sensory innervation in the synovial tissue of the articular capsule31,32; second, the frequency of grossly disordered joints seen on random radiographs of asymptomatic patients suggests that it is unlikely that minor disorders would cause pain.33 To this end, Cyriax22 listed lesions of the facet joints known to cause no problems:

• Gross overriding of the articulating surfaces of the facet joints, occurring as the result of disc resorption in elderly people.

• Gross osteoarthritis of the facets, as seen in more than 50% of people above the age of 4534–38; this is an age-dependent and body mass index (BMI)- and gender-independent phenomenon, most frequently observed at two caudal levels, L4–L5 and L5–S1.39

• The angulation that occurs after a wedge fracture of the vertebral body.

• Retrolisthesis, when the inferior articular process shifts backwards on the superior articular process of the vertebra below.

During the last few decades, however, the balance of the controversy has somewhat tipped towards the conviction that facet joints can be a primary source of low back pain. First, there is an anatomical basis: in contrast to the insensitive synovia, the capsule of the facet joint is richly innervated by nociceptors which become activated when the capsule is stretched or pinched.40 In both pain patients and volunteers, chemical or mechanical stimulation of the facet joints and their nerve supply has been shown to elicit back and/or leg pain.41–43 During spine surgery performed under local anaesthesia, lumbar facet capsule stimulation elicits significant pain in approximately 20% of patients.44 Finally, in a substantial percentage of patients with chronic lower back pain, there is a considerable degree of pain relief after diagnostic injections of the joints with local anaesthetic.45–50 However, some studies have demonstrated extravasation into the epidural space following rupture of the joint capsule if large volumes of anaesthetic agent are used. This may result in an unintentional epidural block, explaining the good diagnostic results.51,52

Potential causes of the ‘facet joint syndrome’

Each facet joint receives dual innervation from medial branches arising from the posterior primary rami at the same level and one level above.53 However, free nerve endings have been found in the capsule only and not in the articular cartilage or the synovial tissue.11,33

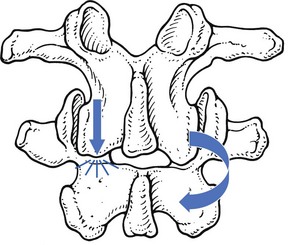

Inflammation could produce pain, as happens during a traumatic arthritis, and it has also been suggested that pain is caused by impingement of a synovial fold between the opposing facets.54,55 Also, inflammatory arthritides, such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and reactive arthritis, may affect the facet joints.56,57 It is not known if advanced osteoarthrosis as such could be the source of a facet syndrome but it is probable that reduced spinal mobility can sometimes predispose to a sprain of the fibrous capsule.58 In degenerative spondylolisthesis, a disorder that causes the whole upper vertebra, including the neural arch and processes, to slip relative to the lower vertebra, the capsules of the facet joints come under permanent traction. This may account for the increased incidence of backache seen in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis.59 A sprain may also follow excessive strain directly on the posterior arch, which sometimes happens as the result of an unintentional twist, usually in extension. Extension of the lumbar spine may be limited by impaction of the inferior articular process on the lamina below. If that happens on one side only, continued application of the extension movement will force the segment towards rotation around the impacted articular process, which draws the inferior articular process of the contralateral facet joint further backwards.60 This may result in sprain of the capsule.61 A similar lesion may result from excessive rotation; rotation is usually limited by the impaction of the facet joint opposite the direction of the movement (normally, the axis of rotation is situated in the posterior third of the disc). If the torque continues, a new axis of rotation will be located in the impacted joint and the contralateral joint will be drawn backwards (Fig. 34.4).62 Although most post-traumatic inflammation subsides spontaneously in the course of a couple of days or weeks, it is conceivable that a chronic ligamentous sprain and lasting pain might occasionally result.

History

The patient presents after hurting his or her back during a particular movement, frequently hyperextension but alternatively hyperextension accompanied by side flexion.63 The pain is strictly unilateral and usually localized, sometimes with slight reference to groin, upper buttock or trochanteric area (Fig. 34.5).64,65 Because a facet joint is a lateral structure, it cannot give rise to central pain.66 However, if there is a bilateral lesion, pain can be bilateral.

Dural symptoms, such as a painful cough or sneeze, are absent.67 Pain usually appears during extension, but standing and lying prone can also be painful.58,68

Clinical examination

The patient stands straight. Usually there is a full range of movement, though extension may be slightly limited. Movements that cause pain at the end of range follow a typical, convergent pattern (Fig. 34.6): for instance, when a left facet joint is at fault, left-sided flexion and extension are painful.69,70 Exceptionally, a divergent pattern can also indicate a facet joint lesion: for a left-side lesion, flexion and side flexion to the right then provoke pain. Sometimes the pain can be provoked only by a combination of extension with side flexion.47

Fig 34.6 Convergent and divergent patterns

A painful arc is always absent, as are dural signs (straight leg raising and neck flexion), typical of discodural interaction; there are no root signs.71 Although some believe that pain on palpation over the facet joint is one of the diagnostic features of the lesion,72,73 palpation of the paravertebral region is non-specific because the tenderness so elicited often results from referral, typical of dural pain.

Because facet joint lesions are rare, the diagnosis is never made without the confirmation of local anaesthetic injection. The technique is set out below but it is important to remember that the results of the block are not always reliable. First, only small amounts of anaesthetic (no more than 1 mL at the dorsal aspect of the capsule) must be used to avoid unintentional epidural injection, which nullifies the test.51,52 Second, numerous studies have documented that the infiltration is associated with a high false-positive rate, ranging from 25 to 40%.74–76

Treatment

Once the diagnosis is made, treatment is infiltration of the posterior aspect of the joint capsule with 10 mg of triamcinolone. In long-standing cases, we prefer to use phenol solution, since the triamcinolone often affords only temporary relief. Others have reported good results after intra-articular injections of a mixture of lidocaine and a corticosteroid suspension,77,37,78 and pain relief is equally good with intra-articular and periarticular injections, indicating that the pain may be of capsular origin, rather than synovial inflammation.79 Good outcomes have also been described after injection with phenol aimed at denervating the joint23 and after radiofrequency ‘denervation’.80,81

Surgery is occasionally performed to treat facet arthropathy despite a lack of evidence supporting fusion for degenerative spinal disorders.82,83

Iliolumbar ligaments

The iliolumbar ligament arises from the tip and lower parts of the transverse process of the fifth lumbar vertebra. It splits into an anterior and a posterior band to insert at the anterior and posterior aspect of the top of the iliac crest (see p. 424).84,85 It plays an important role in the stabilization of the lumbosacral junction. Both anterior and posterior bands restrain flexion of L5 on the sacrum.86 Side flexion is controlled by the contralateral band and extension by the anterior bands. The iliolumbar ligaments are also thought to be important in maintaining torsional stability of the lumbosacral junction.87 Because of the specific orientation of the facets of the lumbosacral junction, some rotation is permitted between L5 and S1, in contrast to the lack of rotation at the more superior lumbar joints, and it seems reasonable to speculate that the iliolumbar ligaments fulfil the same function as the articular stabilization of the higher level.88,89 The stabilizing and anchoring function of the ligaments also modifies the outcome of acute disc displacements. At the L5–S1 level, the strong ligament prevents gross lateral deviations, as is usually seen in L3–L4 or L4–L5 protrusions. However, it is possible for the ligaments to become stretched during long-standing disc displacements. The patient may then suffer from persistent and chronic pain after the primary lesion has been adequately treated by manipulation, traction or surgery.90,91

Alternatively, iliolumbar strain can originate from sudden or repeated overstretching, as in forced rotation during flexion.92 Our personal experience includes instances in soccer players, apparently as the result of repeated lumbosacral torsions; the differential diagnosis of groin pain in such circumstances includes strain of the iliolumbar ligaments.

History

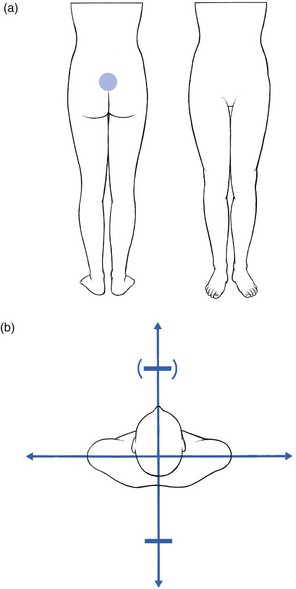

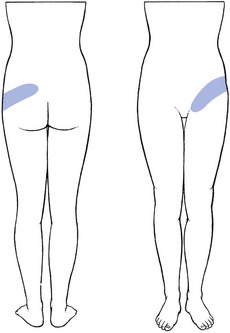

The patient suffers unilateral or bilateral localized pain at the lower lumbar area. The pain may spread along the iliac crest to the groin (Fig. 34.7).93,94

Fig 34.7 Pain reference in iliolumbar sprain.

Clinical examination

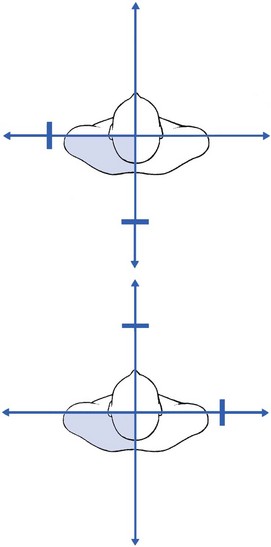

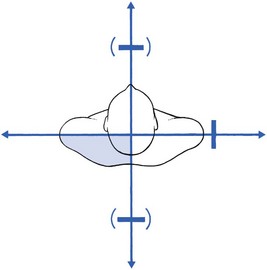

No deviation is visible in the standing position. There is a full range of movement. Side flexion away from the painful side can cause pain at the upper sacroiliac region or in the groin (Fig. 34.8). Sometimes there is also pain at the end of flexion or extension. There are no dural or nerve root signs.

Fig 34.8 Patterns in iliolumbar lesions.

Supraspinous and interspinous ligaments

In vivo measurements taken from lateral radiographs of lumbar spines showed that the interspinous distance extends up to almost four times during full flexion,96 which could imply that the interspinous ligament is lax in the upright position and becomes taut only in the extremes of flexion. However, the orientation of the fibres in this ligament, which is obliquely from posterosuperior to anteroinferior, allows it to be active over a large range of motions during flexion.97,98 Overstretching of the ligaments is therefore very rare, and it is doubtful whether this could be a cause of backache.

Autopsy studies of a large number of subjects have shown that, in subjects over 20 years, over 20% have ruptures of one or more of their supraspinous ligaments, occurring mostly at L4–L5 and L5–S1 segments.99 These figures strongly suggest that ruptures of the supraspinous ligaments, defined by Newman as ‘sprung back’,100 rarely are, of themselves, the cause of low back pain. It is important to realize that, in disc degeneration, an intact supraspinous ligament probably plays an important role in the prevention of posterior displacements. In such circumstances, the posterior fibres of the annulus fibrosus and the posterior longitudinal ligament no longer limit forward flexion because the instantaneous axis of rotation is not at the nucleus but more posteriorly, behind the posterior longitudinal ligament (Fig. 34.9).101 Flexion of the spine is then controlled by the supraspinous ligament (see p. 422). Although a ‘sprung back’ is certainly not the primary cause of pain, it can add to segmental instability and recurrent disc displacements. For this reason, sclerosis of the interspinous and supraspinous ligaments is part of the treatment of recurrent disc displacements (see p. 579).

During full extension, the interspinous distances decrease to between 2 and 4 mm and the processes may meet as the bifid ligament buckles laterally on both sides.102 The ligament is not trapped between the processes and, if pain originates in ‘kissing spines’, it is due to irritation of the periosteum or an adventitial bursa between the abutting spinous processes.103,104

History

There is localized and central pain (Fig. 34.10a), which started after an unintentional hyperextension strain – for instance, bending backwards during gymnastics or diving.105 The pain does not spread over a large area. The patient states that standing upright and backward bending cause discomfort. There are no dural symptoms.

Clinical examination

Extension causes local pain (Fig. 34.10b). Sometimes the end of flexion is also painful. Side flexions are usually free. The lesion is very localized and the patient often indicates the site with one finger. A tender spot, usually at the tips of two consecutive spinal processes, can be palpated. There are no dural or root signs.

References

1. Pedersen, HE, Blunck, CFJ, Gardner, E, Anatomy of lumbosacral posterior rami and meningeal branches of spinal nerves. J Bone Joint Surg 1956; 38A:377. ![]()

2. Bogduk, N, The innervation of the lumbar spine. Spine 1983; 8:286–293. ![]()

3. Stillwell, DL, Nerve supply of vertebral colum. Anat Rec 1956; 125:139. ![]()

4. Hackett, GS. Joint Ligament Relaxation Treated by Fibro-osseous Proliferation. Springfield: Thomas; 1956.

5. Hirsch, C, Studies on the mechanism of low-back pain. Acta Orthop Scand 1951; 20:261–274. ![]()

6. Kuslich, SD, Ulstrom, CL, The tissue origin of low back pain and sciatica. Orthop Clin North Am 1991; 22:181–187. ![]()

7. Troisier, O. Sémiologie et traitement des algies discales et ligamentaires du rachis. Paris: Masson; 1973.

8. Barbor R. Treatment for chronic low back pain. Proc IVth Int Congr Phys Med. Paris, 1964.

9. MacKenzie, RA. The Lumbar Spine. Waikane: Spinal Publications; 1981.

10. Ongley, MJ, Klein, RG, Thomas, AD, et al, A new approach to the treatment of chronic low back pain. Lancet 1987; 18:143–146. ![]()

11. Wyke, B. The neurology of low back pain. In Jayson MIV, ed.: The Lumbar Spine and Back Pain, 2nd ed, Tunbridge Wells: Pitman Medical, 1980.

12. Stokes, I, Frymoyer, JW, Segmental motion and instability. Spine 1987; 12:688–691. ![]()

13. Hedtmann, A, Steffen, R, Methfessel, J, et al, Measurements of human lumbar spine ligaments during loaded and unloaded motion. Spine 1989; 14:175–185. ![]()

14. McCulloch, JA, McNab, I. Sciatica and Chymopapain. London: Williams & Wilkins; 1983.

15. Henchoz, Y, Kai-Lik So, A, Exercise and nonspecific low back pain: a literature review. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75(5):533–539. ![]()

16. Peterson, TH, Injection treatment for back pain. Am J Orthop 1963; 26:320–325. ![]()

17. Myers, A, Prolotherapy treatment of low back pain and sciatica. Bull Hosp Joint Dis 1961; 2:48–55. ![]()

18. Hunt, WE, Baird, WC, Complications following injections of sclerosing agent to precipitate fibro-osseous proliferation. J Neurosurg 1961; 18:461–465. ![]()

19. Keplinger, JE, Bucy, PC, Paraplegia from treatment with sclerosing agents – a report of a case. JAMA 1960; 73:1333–1336. ![]()

20. Schneider, RC, Williams, JI, Liss, L, Fatality after injection of sclerosing agent to precipitate fibro-osseous proliferation. JAMA 1959; 170:1768–1772. ![]()

21. Dodd, H. Treatment of varicose veins with phenol solution. BMJ. 1948; ii:838.

22. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol I, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

23. Silvers, HR, Lumbar percutaneous facet rhizotomy. Spine 1990; 15:36–40. ![]()

24. Watson, JD, Shay, BL, Treatment of chronic low-back pain: a 1-year or greater follow-up. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(9):951–958. ![]()

25. Klein, RG, Eek, BC, DeLong, WB, Mooney, V, A randomized double-blind trial of dextrose–glycerine–phenol injections for chronic, low back pain. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6(1):23–33. ![]()

26. Goldthwait, JE. The lumbosacral articulation: an explanation of many cases of lumbago, sciatica and paraplegia. Boston Med Surg J. 1911; 164:365.

27. Ghormley, RK. Low back pain with special reference to the articular facets with presentation of an operative procedure. JAMA. 1933; 101:17733–17777.

28. Lewin, T, Moffett, B, Vidik, A, The morphology of the lumbar synovial intervertebral joints. Acta Morphol Neerl Scand 1962; 4:299–319. ![]()

29. Hirsch, C, Inglemark, B, Miller, M, The anatomical basis for low back pain. Acta Orthop Scand 1963; 33:1. ![]()

30. Mooney, V, Robertson, J, The facet syndrome. Clin Orthop 1976; 115:149–156. ![]()

31. Wyke, B, Articular neurology – a review. Physiotherapy 1972; 58:94–99. ![]()

32. Grönblad, M, Korkala, O, Konttinen, Y, et al, Silver impregnation and immunohistochemical study of nerves in lumbar facet joint plical tissue. Spine 1991; 16:34–38. ![]()

33. Jackson, RP, The facet joint syndrome: myth or reality? Clin Orthop 1992; 279:110–121. ![]()

34. Lewin, T, Osteoarthrosis in lumbar synovial joints. Acta Orthop Scand. 1966;73(suppl). ![]()

35. Park, WM. The place of radiology in the investigation of low back pain. Clin Rheum Dis. 1980; 6:93–132.

36. Wiesel, SW, Bernini, P, Rothman, RH. Diagnostic studies in evaluating disease and aging in the lumbar spine. In: The Aging Lumbar Spine. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1982.

37. Sanders, HWA, Klinische betekenis van degeneratieve afwijkingen van de lumbale wervelkolom en consequenties van het aantonen ervan. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1983; 127:1374–1385. ![]()

38. Alyas, F, Turner, M, Connell, D, MRI findings in the lumbar spines of asymptomatic, adolescent, elite tennis players. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(11):836–841. ![]()

39. Abbas, J, Hamoud, K, Peleg, S, et al, Facet joints arthrosis in normal and stenotic lumbar spines. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(24):E1541–E1546. ![]()

40. Cavanaugh, JM, Ozaktay, AC, Yamashita, HT, King, AI, Lumbar facet pain: biomechanics, neuroanatomy and neurophysiology. J Biomechanics 1996; 29:1117–1129. ![]()

41. Hirsch, C, Ingelmark, BE, Miller, M, The anatomical basis for low back pain: studies on the presence of sensory nerve endings in ligamentous, capsular and intervertebral disc structures in the human lumbar spine. Acta Orthop Scand 1963; 33:1–17. ![]()

42. Marks, RC, Houston, T, Thulbourne, T, Facet joint injection and facet nerve block: a randomized comparison in 86 patients with chronic low back pain. Pain 1992; 49:325–328. ![]()

43. McCall, IW, Park, WM, O’Brien, JP, Induced pain referral from posterior lumbar elements in normal subjects. Spine 1979; 4:441–446. ![]()

44. Kuslich, SD, Ulstrom, CL, Michael, CJ, The tissue origin of low back pain and sciatica: a report of pain response to tissue stimulation during operations on the lumbar spine using local anesthesia. Orthop Clin North Am 1991; 22:181–187. ![]()

45. Carrera, GF, Lumbar facet joint injection in low-back pain and sciatica. Neuroradiology 1980; 137:665–667. ![]()

46. Destouet, JM, Lumbar facet joint injection: indication, technique, clinical correlation and preliminary results. Radiology 1982; 145:321–325. ![]()

47. Helbig, T, Lee, CK, The lumbar facet syndrome. Spine 1988; 13:61–64. ![]()

48. Jackson, RP, Jacobs, RR, Montesano, PX, Facet joint injection in low-back pain. A prospective statistical study. Spine 1988; 13:966–971. ![]()

49. Schwarzer, AC, Aprill, CN, Derby, R, et al, Clinical features of patients with pain stemming from the zygapophyseal joints. Is the lumbar facet syndrome a clinical entity? Spine 1994; 19:1132–1137. ![]()

50. van Kleef, M, Vanelderen, P, Cohen, SP, et al, Pain originating from the lumbar facet joints. Pain Pract. 2010;10(5):459–469. ![]()

51. Morane, R, O’Connell, D, Walsh, MG, The diagnostic value of facet joint injections. Spine 1988; 13:1407–1410. ![]()

52. Döry, M, Arthrography of the lumbar facet joints. Radiology 1981; 140:23–27. ![]()

53. Bogduk, N. Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum, 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1997.

54. Giles, LGF. Lumbo-sacral and cervical zygapophyseal joint inclusions. Manual Med. 1986; 2:89.

55. Konttinen, Y, Grönblad, M, Korkala, O, et al, Immunohistochemical demonstration of subclasses of inflammatory cells and active, collagen-producing fibroblasts in the synovial plicae of lumbar facet joints. Spine 1990; 15:387–390. ![]()

56. Guillaume, MP, Hermanus, N, Peretz, A, Unusual localisation of chronic arthropathy in lumbar facet joints after parvovirus B19 infection. Clin Rheumatol 2002; 21:306–308. ![]()

57. de Vlam, K, Mielants, H, Verstaete, KL, Veys, EM, The zygapophyseal joint determines morphology of the enthesophyte. J Rheumatol 2000; 27:1732–1739. ![]()

58. Eisenstein, SM, Parry, CR, The lumbar facet arthrosis syndrome: clinical presentation and articular surface changes. J Bone Joint Surg 1987; 69B:3–7. ![]()

59. Herkowitz, HN, Spine update: degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Spine 1995; 20:1084–1090. ![]()

60. Kuo, CS, Hu, HT, Lin, RM, et al, Biomechanical analysis of the lumbar spine on facet joint force and intradiscal pressure – a finite element study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010; 11:151. ![]()

61. Yang, JH, King, AJ, Mechanism of facet load transmission as a hypothesis for low back pain. Spine 1984; 9:557–565. ![]()

62. Twomey, LT, Taylor, J, Furniss, MM, Unsuspected damage to lumbar facet joints after motor-vehicle accidents. Med J Aust 1989; 151:210–217. ![]()

63. Yang, KH, King, AI, Mechanism of facet load transmission as a hypothesis for low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1984;9(6):557–565. ![]()

64. Fukui, S, Ohseto, K, Shiotani, M, et al, Distribution of referred pain from the lumbar zygapophyseal joints and dorsal rami. Clin J Pain 1997; 13:303–307. ![]()

65. McCall, IW, Park, WM, O’Brien, JP, Induced pain referral from posterior lumbar elements in normal subjects. Spine 1979; 4:441–446. ![]()

66. Depalma, MJ, Ketchum, JM, Trussell, BS, et al, Does the location of low back pain predict its source? PMR. 2011;3(1):33–39. ![]()

67. Revel, M, Poiraudeau, S, Auleley, GR, et al, Capacity of the clinical picture to characterize low back pain relieved by facet joint anesthesia. Spine 1998; 23:1972–1977. ![]()

68. Lynch, MC, Taylor, JF, Facet joint injection for low back pain. J Bone Joint Surg 1986; 68B:138–141. ![]()

69. Lippitt, AB, The facet joint and its role in spine pain: management with facet joint injections. Spine 1984; 9:746–750. ![]()

70. Selby, DK, Paris, SC. Anatomy of facet joints and its correlation with low back pain. Contemp Orthop. 1981; 312:1097–1103.

71. Schroeder, WF, The facet syndrome: diagnosis and treatment, 1984.

72. Lewinnek, GE, Warfield, CA, Facet joint degeneration as a cause of low back pain. Clin Orthop 1986; 213:216–222. ![]()

73. White, AH, Injection technique for the diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 1983;14(3):353–367. ![]()

74. Manchikanti, L, Pampati, V, Fellows, B, Bakhit, CE, The diagnostic validity and therapeutic value of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks with or without adjuvant agents. Curr Rev Pain 2000; 4:337–344. ![]()

75. Dreyfuss, PH, Dreyer, SJ, Lumbar zygapophysial joint (facet) injections. Spine J 2003; 3:50S–59S. ![]()

76. Schwarzer, AC, Aprill, CN, Derby, R, et al, The false positive rate of uncontrolled diagnostic blocks of the lumbar zygapophyseal joints. Pain 1994; 58:195–200. ![]()

77. Pneumaticos, SG, Chatziioannou, SN, Hipp, JA, et al, Low back pain: prediction of short-term outcome of facet joint injection with bone scintigraphy. Radiology 2006; 238:693–698. ![]()

78. Murtagh, FR, Computed tomography and fluoroscopy guided anaesthesia and steroid injection in facet syndrome. Spine 1988; 13:686–689. ![]()

79. Lilius, G, Laasonen, EM, Myllynen, P, Lumbar facet joint syndrome; a randomised clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg 1989; 71B:681–684. ![]()

80. Burton, CV, Percutaneous radiofrequency facet denervation. Appl Neurophysiol 1976/77; 39:80–86. ![]()

81. Mehta, M, Sluiiter, ME, The treatment of chronic backpain – a preliminary survey of radiofrequency denervation of the posterior vertebral joints. Anaesthesia 1979; 34:768–775. ![]()

82. Gibson, JN, Waddell, G, Grant, IC, Surgery for degenerative lumbar spondylosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000; 3. ![]()

83. Deyo, RA, Nachemson, A, Mirza, SK, Spinal-fusion surgery: the case for restraint. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:722–726. ![]()

84. Mitchell, GAG. The lumbosacral junction. J Bone Joint Surg. 1934; 16:233–254.

85. Basadonna, P-T, Gasparini, D, Rucco, V, Illiolumbar ligament insertions; in vivo anatomic study. Spine 1996; 21:2313–2316. ![]()

86. Leong, JCY, Luk, KDK, Chow, DHK, Woo, CW, The biomechanical functions of the iliolumbar ligament in maintaining stability of the lumbosacral junction. Spine 1987; 12:669–674. ![]()

87. Chow, DHK, Luk, KDK, Leong, JCY, Woo, CX, Torsional stability of the lumbosacral junction; significance of the iliolumbar ligament. Spine 1989; 14:611–615. ![]()

88. Boebel, R, Anatomische Untersuchungen am Ligamentum iliolumbale. Z Orthop 1961; 95–92. ![]()

89. Yamamoto, I, Panjabi, MM, Oxlands, TR, Crisco, JJ, The role of the iliolumbar ligament in the lumbosacral junction. Spine 1990; 15:1138–1141. ![]()

90. Sims, JA, Moorman, SJ, The role of the iliolumbar ligament in low back pain. Med Hypotheses. 1996;46(6):511–515. ![]()

91. Pool-Goudzwaard, A, Hoek van Dijke, G, Mulder, P, et al, The iliolumbar ligament: its influence on stability of the sacroiliac joint. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2003;18(2):99–105. ![]()

92. Collée, G, Dijkmans, BA, Vandenbroucke, JP, et al, A clinical epidemiological study in low back pain. Description of two clinical syndromes. Br J Rheumatol. 1990;29(5):354–357. ![]()

93. Collée, G, Dijkmans, AC, Vandenbroucke, JP, Cats, A, Iliac crest pain syndrome in low back pain: frequency and features. J Rheumatol 1991; 18:1064–1067. ![]()

94. Fairbans, JCT, O’Brien, JP, The iliac crest syndrome: a treatable cause of low-back pain. Spine 1983; 8:220–224. ![]()

95. Naeim, F, Froetscher, L, Hirschberg, GG, Treatment of the chronic iliolumbar syndrome by infiltration of the iliolumbar ligament. West J Med. 1982;136(4):372–374. ![]()

96. Pearcy, MJ, Tibrewal, SB, Lumbar intervertebal disc and ligament deformations measured in vivo. Clin Orthop 1984; 191:281–286. ![]()

97. Silver, PHS. Direct observations of changes in tension in the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments during flexion and extension of the vertebral column in man. J Anat. 1954; 88:550.

98. Adams, MA, Hutton, WC, Stott, JRR, The resistance to flexion of the lumbar intervertebral joint. Spine 1980; 5:245. ![]()

99. Rissanen, PM, The surgical anatomy and pathology of the supraspinous ligaments of the lumbar spine, with special references to ligament ruptures. Acta Orthop Scand. 1966;46(suppl). ![]()

100. Newman, PH, The sprung back. J Bone Joint Surg 1952; 34B:30. ![]()

101. Hoag, JM, Kosek, M, Moser, JR, Kinematic analysis and classification of vertebral motion. Part I. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1960; 59:899. ![]()

102. Heylings, DJA, Supraspinous and interspinous ligaments of the human lumbar spine. J Anat 1978; 125:127. ![]()

103. Maes, R, Morrison, WB, Parker, L, et al, Lumbar interspinous bursitis (Baastrup disease) in a symptomatic population: prevalence on magnetic resonance imaging. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(7). ![]()

104. Beks, JWF, Kissing spines: fact or fancy? Acta Neurochir 1989; 100:134–135. ![]()

105. Clifford, PD, Baastrup disease. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2007;36(10):560–561. ![]()