Chapter 489 The Leukemias

489.1 Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

Etiology

In virtually all cases, the etiology of ALL is unknown, although several genetic and environmental factors are associated with childhood leukemia (Table 489-1). Exposure to medical diagnostic radiation both in utero and in childhood has been associated with an increased incidence of ALL. In addition, published descriptions and investigations of geographic clusters of cases have raised concern that environmental factors can increase the incidence of ALL. Thus far, no such factors other than radiation have been identified in the USA. In certain developing countries, there has been an association between B-cell ALL and Epstein-Barr viral infections.

Cellular Classification

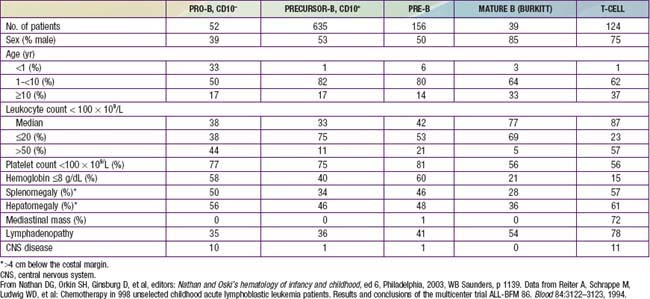

The classification of ALL depends on characterizing the malignant cells in the bone marrow to determine the morphology, phenotypic characteristics as measured by cell membrane markers, and cytogenetic and molecular genetic features. Morphology alone usually is adequate to establish a diagnosis, but the other studies are essential for disease classification, which can have a major influence on the prognosis and the choice of appropriate therapy. The most important distinguishing morphologic feature is the French-American-British (FAB) L3 subtype, which is evidence of a mature B-cell leukemia. The L3 type, also known as Burkitt leukemia, is one of the most rapidly growing cancers in humans and requires a different therapeutic approach than other subtypes of ALL. Phenotypically, surface markers show that about 85% of cases of ALL are derived from progenitors of B cells, about 15% are derived from T cells, and about 1% are derived from B cells. A small percentage of children with leukemia have a disease characterized by surface markers of both lymphoid and myeloid derivation. Immunophenotypes often correlate to disease manifestations (Table 489-2).

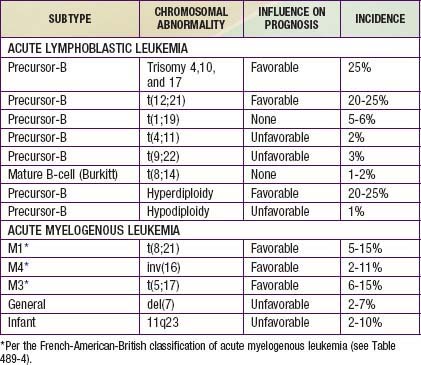

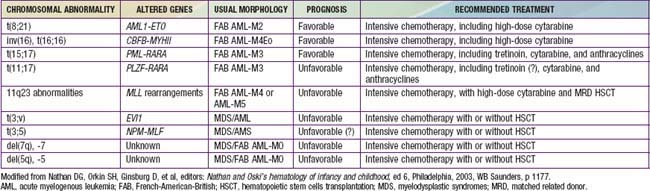

Chromosomal and genetic abnormalities are found in most patients with ALL (Table 489-3, Fig. 489-1). The abnormalities, which may be related to chromosomal number, translocations, or deletions, provide important prognostic information. The identification of the leukemia-specific fusion-gene sequences in archived neonatal blood spots of some children who develop ALL at a later date indicates the importance of in utero events in the initiation of the malignant process, but the long lag period before the onset of the disease in some children, reported to be as long as 14 yr, supports the concept that additional genetic modifications also are required for disease expression. The polymerase chain reaction and fluorescence in situ hybridization techniques offer the ability to pinpoint molecular genetic abnormalities and to detect small numbers of malignant cells during follow-up and are of proven clinical utility. The development of DNA microanalysis makes it possible to analyze the expression of thousands of genes in the leukemic cell. This technique promises to further enhance the understanding of the fundamental biology and to provide clues to the therapeutic approach of ALL. Some effectors of critical signal transduction pathways have already been implicated in the pathogenesis of ALL using this technique.

Clinical Manifestations

On physical examination, findings of pallor, listlessness, purpuric and petechial skin lesions, or mucous membrane hemorrhage can reflect bone marrow failure (Chapter 487). The proliferative nature of the disease may be manifested as lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, or, less commonly, hepatomegaly. In patients with bone or joint pain, there may be exquisite tenderness over the bone or objective evidence of joint swelling and effusion. Nonetheless, with marrow involvement, deep bone pain may be present but tenderness will not be elicited. Rarely, patients show signs of increased intracranial pressure that indicate leukemic involvement of the CNS. These include papilledema (see Fig. 487-3), retinal hemorrhages, and cranial nerve palsies. Respiratory distress usually is related to anemia but can occur in patients with an obstructive airway problem (wheezing) due to a large anterior mediastinal mass (e.g., in the thymus or nodes). This problem is most typically seen in adolescent boys with T-cell ALL. T-cell ALL also has a higher leukocyte count.

Precursor B-cell ALL (CD10+ or common acute lymphoblastic leukemia antigen [CALLA] positive) is the most common immunophenotype (see Table 489-2), with onset at 1-10 yr of age. The median leukocyte count at presentation is 33,000, although 75% of patients have counts <20,000; thrombocytopenia is seen in 75% of patients, and hepatosplenomegaly is seen in 30-40% of patients. In all types of leukemia, CNS symptoms are seen at presentation in 5% of patients (5-10% have blasts in the CSF). Testicular involvement is rarely evident at diagnosis, but prior studies have indicated occult involvement in 25% of boys. There is no indication for testicular biopsy.

Treatment

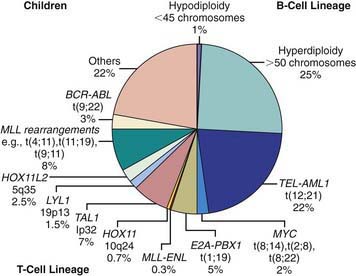

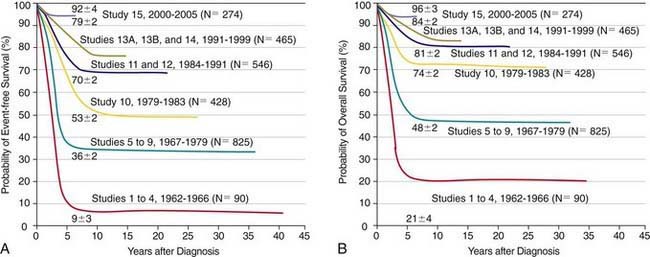

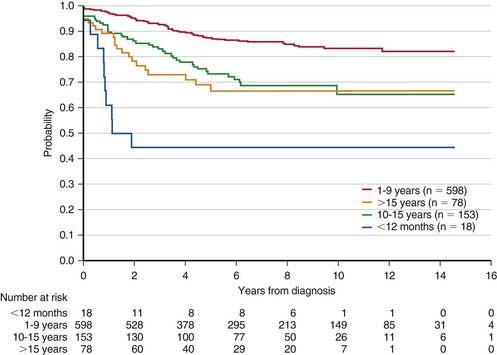

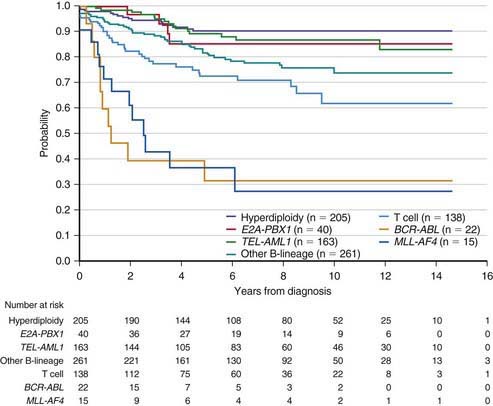

The single most important prognostic factor in ALL is the treatment: Without effective therapy, the disease is fatal. The survival rates of children with ALL since the 1970s have improved as the results of clinical trials have improved the therapies and outcomes (Fig. 489-2). Survival is also related to age (Fig. 489-3) and subtype (Fig. 489-4).

Figure 489-3 Kaplan-Meier estimates of event-free survival according to age at diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

(From Pui CH, Robinson LL, Look AT: Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, Lancet 371:1030–1042, 2008.)

Figure 489-4 Kaplan-Meier analysis of event-free survival according to biological subtype of leukemia.

(From Pui CH, Robinson LL, Look AT: Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, Lancet 371:1030–1042, 2008.)

In the future, treatment also may be stratified by gene expression profiles of leukemic cells or the presence of minimal residual disease. In particular, gene expression arrays induced by exposure to the chemotherapeutic agent can predict which patients have drug-resistant ALL. Pharmacogenetic testing of the thiopurine S-methyltransferase gene, which converts mercaptopurine or thioguanine (both prodrugs) into active chemotherapeutic agents, can identify rapid metabolizers (associated with toxicity) or slow metabolizers (associated with treatment failure), thus optimizing drug dosing (Chapter 56).

Treatment of Relapse

The major impediment to a successful outcome is relapse of the disease. Relapse occurs in the bone marrow in 15-20% of patients with ALL and carries the most serious implications, especially if it occurs during or shortly after completion of therapy. Intensive chemotherapy with agents not previously used in the patient followed by allogeneic stem cell transplantation can result in long-term survival for some patients with bone marrow relapse (Chapter 129).

The most current information on treatment of childhood ALL is available in the PDQ (Physician Data Query) on the National Cancer Institute website (www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/childALL/healthprofessional/).

Prognosis

Most children with ALL can now be expected to have long-term survival, with the survival rate >80% at 5 yr from diagnosis (see Fig. 489-2). The most important prognostic factor is the choice of appropriate risk-directed therapy, with the type of treatment chosen according to the subtype of ALL, the initial white blood count, the age of the patient, and the rate of response to initial therapy. Characteristics generally believed to adversely affect outcome include age <1 yr or >10 yr at diagnosis, a leukocyte count of >50,000/µL at diagnosis, T-cell immunophenotype, or a slow response to initial therapy. Chromosomal abnormalities, including hypodiploidy, the Philadelphia chromosome, and MLL gene rearrangements, and certain mutations, including deletion of the IKZF1 gene, portend a poorer outcome. More-favorable characteristics include a rapid response to therapy, hyperdiploidy, trisomy of specific chromosomes, and rearrangements of the TEL/AML1 genes.

Balduzzi A, Valsecchi MG, Uderzo C, et al. Chemotherapy versus allogeneic transplantation for very-high-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in first complete remission: comparison by genetic randomization in an international prospective study. Lancet. 2005;366:635-642.

Bercovich D, Ganmore I, Scott M, et al. Mutations of JAK2 in acute lymphoblastic leukaemias associated with Down’s syndrome. Lancet. 2008;372:1484-1492.

Borowitz MJ, Devidas M, Hunger SP, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and its relationship to other prognostic factors: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Blood. 2008;111:5477-5485.

Claudio J, Rocha C, Cheng C, et al. Pharmacogenetics of outcome in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2005;105:4752-4758.

Eapen M, Rubinstein P, Zhang MJ, et al. Outcomes of transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood and bone marrow in children with acute leukaemia: a comparison study. Lancet. 2007;369:1947-1954.

Greaves M. In utero origins of childhood leukaemia. Early Hum Dev. 2005;81:123-129.

Hijiya N, Hudson MM, Lensing S, et al. Cumulative incidence of secondary neoplasms as a first event after childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA. 2007;297:1207-1215.

Holleman A, Cheok MH, den Boer ML, et al. Gene-expression patterns in drug-resistant acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells and response to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:533-542.

Jansen NCAJ, Kingma A, Schuitema A, et al. Neuropsychological outcome in chemotherapy-only-treated children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3025-3030.

Kadan-Lottick NS, Brouwers P, Breiger D, et al. A comparison of neurocognitive functioning in children previously randomized to dexamethasone or prednisone in the treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:1746-1752.

Kadan-Lottick NS, Ness KK, Bhatia S, et al. Survival variability by race and ethnicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA. 2003;290:2008-2014.

Merzenich H, Schmiedel S, Bennack S, et al. Childhood leukemia in relation to radio frequency electromagnetic fields in the vicinity of TV and radio broadcast transmitters. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1169-1178.

Mitchell C, Hall G, Clarke RT. Acute leukemia in children: diagnosis and management. BMJ. 2009;338:1491-1495.

Mullighan CG, et al. Deletion of IKZF1 and prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:470-480.

Murray MJ, Tang T, Ryder C, et al. Childhood leukaemia masquerading as juvenile idiopathic arthritis. BMJ. 2004;329:959-961.

Papaemmanuil E, Hosking FJ, Vijayakrishnan J, et al. Loci on 7p12.2, 10q21.2 and 14q11.2 are associated with risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1006-1010.

Patel SR, Ortin M, Cohen BJ, et al. Revaccination of children after completion of standard chemotherapy for acute leukemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:635-642.

Pieters R, Schrappe M, De Lorenzo P, et al. A treatment protocol for infants younger than 1 year with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (Interfant-99): an observational study and a multicentre randomized trial. Lancet. 2007;370:240-250.

Pui CH, Campana D, Pei D, et al. Treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2730-2740.

Pui CH, Cheng C, Leung W, et al. Extended follow-up of long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:640-648.

Pui CH, Evans WE. Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:166-178.

Pui CH, Relling MV, Downing JR. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1535-1548.

Pui CH, Robinson LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2008;371:1030-1042.

Ramanujachar R, Richards S, Hann I, et al. Adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: emerging from the shadow of paediatric and adult treatment protocols. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47:748-756.

Ravindranath Y. Down syndrome and leukemia: new insights into the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44:1-7.

Saha V. Simplifying treatment for children with ALL. Lancet. 2007;369:82-83.

Schrappe M. Mitoxantrone in first-relapse paediatric ALL: the ALL R2 trial. Lancet. 2011;376:1968-1969.

Shaw PJ, Kan F, Ahn KW, et al. Outcomes of pediatric bone marrow transplantation for leukemia and myelodysplasia using matched sibling, mismatched related, or matched unrelated donors. Blood. 2010;116(19):4007-4015.

Stanulla M, Schaeffeler E, Flohr T, et al. Thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) genotype and early treatment response to mercaptopurine in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA. 2005;293:1485-1489.

Stanulla M, Schünermann HJ. Thioguanine versus mercaptopurine in childhood ALL. Lancet. 2006;368:1304-1306.

Temming P, Jenney MEM. The neurodevelopmental sequelae of childhood leukemia and its treatment. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:936-940.

Treviño LR, Yang W, French D, et al. Germline genomic variants associated with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nature Genetics. 2009;41:1001-1005.

Winick NJ, Carroll WL, Hunger SP. Childhood leukemia—new advances and challenges. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:601-604.

Yang JJ, Cheng C, Devidas M, et al. Ancestry and pharmacogenomics of relapse in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43(3):237-241.

Yang JJ, Cheng C, Yang W, et al. Genome-wide interrogation of germline genetic variation associated with treatment response in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA. 2009;301:393-403.

Zweidler-McKay PA, Hilden JM. The ABCs of infant leukemia. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2008;38:73-104.

489.2 Acute Myelogenous Leukemia

Epidemiology

AML accounts for 11% of the cases of childhood leukemia in the USA; it is diagnosed in approximately 370 children annually. The relative frequency of AML increases in adolescence, representing 36% of cases of leukemia in 15-19 yr olds. One subtype, acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), is more common in certain other regions of the world, but incidence of the other types is generally uniform. Several chromosomal abnormalities associated with AML have been identified, but no predisposing genetic or environmental factors can be identified in most patients (see Table 489-1). Nonetheless, a number of risk factors have been identified, including ionizing radiation, chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., alkylating agents, epipodophyllotoxin), organic solvents, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, and certain syndromes: Down syndrome, Fanconi anemia, Bloom syndrome, Kostmann syndrome, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, Diamond-Blackfan syndrome, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, and neurofibromatosis type 1.

Cellular Classification

The characteristic feature of AML is that >20% of bone marrow cells on bone marrow aspiration or biopsy touch preparations constitute a fairly homogeneous population of blast cells, with features similar to those that characterize early differentiation states of the myeloid-monocyte-megakaryocyte series of blood cells. The most common classification of the subtypes of AML is the FAB system (Table 489-4). Although this system is based on morphologic criteria alone, current practice also requires the use of flow cytometry to identify cell surface antigens and use of chromosomal and molecular genetic techniques for additional diagnostic precision and also to aid the choice of therapy. The World Health Organization (WHO) has proposed a new classification system that incorporates morphology, chromosome abnormalities, and specific gene mutations. This system provides significant biologic and prognostic information.

Table 489-4 FRENCH-AMERICAN-BRITISH (FAB) CLASSIFICATION OF ACUTE MYELOGENOUS LEUKEMIA

| SUBTYPE | COMMON NAME |

|---|---|

| M0 | Acute myeloblastic leukemia without differentiation |

| M1 | Acute myeloblastic leukemia without maturation |

| M2 | Acute myeloblastic leukemia with maturation |

| M3 | Acute promyeloblastic leukemia |

| M4 | Acute myelomonocytic leukemia |

| M5 | Acute monocytic leukemia |

| M6 | Erythroleukemia |

| M7 | Acute megakaryocytic leukemia |

Diagnosis

Analysis of bone marrow aspiration and biopsy specimens of patients with AML typically reveals the features of a hypercellular marrow consisting of a monotonous pattern of cells with features that permit FAB subclassification of disease. Flow cytometry and special stains assist in identifying myeloperoxidase-containing cells, thus confirming both the myelogenous origin of the leukemia and the diagnosis. Some chromosomal abnormalities and molecular genetic markers are characteristic of specific subtypes of disease (see Tables 489-3 and 489-5).

Treatment

Aggressive multiagent chemotherapy is successful in inducing remission in about 85-90% of patients. Targeting therapy to genetic markers may be beneficial (see Table 489-5). Up to 5% of patients die of either infection or bleeding before a remission can be achieved. Matched-sibling bone marrow or stem cell transplantation after remission has been shown to achieve long-term disease-free survival in 60-70% of patients. Continued chemotherapy for patients who do not have a matched sibling donor is generally less effective than marrow transplantation but nevertheless is curative in about 45-50% of patients. However, for selected patients with favorable prognostic features [t(8;21); t(15;17); inv(16); FAB M3] and improved outcome with chemotherapy, matched sibling stem cell transplantation is recommended only after a relapse. Matched unrelated donor (MUD) stem cell transplants may be effective therapy, but they carry the risk of significant graft versus host disease as well as the complications associated with intensive myeloablative therapy. MUD transplants are usually reserved for patients who have a relapse. However, patients with unfavorable prognostic features (e.g., monosomy 7 and 5, 5q-, and 11q23 abnormalities) who have inferior outcome with chemotherapy might benefit from MUD stem cell transplant in first remission.

The most current information on treatment of AML is available in the PDQ (Physician Data Query) on the National Cancer Institute website (www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/childAML/healthprofessional/).

Fernandez HF, Sun Z, Yai X, et al. Anthracycline dose intensification in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1249-1259.

Gentles AJ, Plevritis SK, Majeti R, et al. Association of a leukemic stem cellgene expression signature with clinical outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA. 2010;304(24):2706-2714.

Mardis ER, Ding L, Dooling DJ, et al. Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1058-1066.

Raimondi SC, Chang MN, Ravindranth Y, et al. Chromosome abnormalities in 478 children with acute myeloid leukemia: clinical characteristics and treatment outcome in cooperative group study—POG 8821. Blood. 1999;94:3707-3716.

Ross ME, Mahfouz R, Onciu M, et al. Gene expression profiling of pediatric acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2004;104:3679-3687.

Rubnitz JE, Gibson B, Smith FO. Acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:21-51.

Schlenk RF, Dohner K, Krauter J, et al. Mutations and treatment outcome in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1909-1918.

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffee ES. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissue, ed 4. Lyons: International Agency for Research in Cancer; 2008.

Woods WG, Neudorf S, Gold S, et al. A comparison of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, autologous bone marrow transplantation, and aggressive chemotherapy in children with acute myeloid leukemia in remission. Blood. 2001;97:56-62.

489.3 Down Syndrome and Acute Leukemia and Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder

Acute leukemia occurs about 15-20 times more frequently in children with Down syndrome than in the general population (Chapter 76). The ratio of ALL to AML in patients with Down syndrome is the same as that in the general population. The exception is during the first 3 yr of life, when AML is more common. In children with Down syndrome who have ALL, the expected outcome of treatment is slightly inferior to that for other children. Patients with Down syndrome demonstrate a remarkable sensitivity to methotrexate and other antimetabolites, which can result in substantial toxicity if standard doses are administered. In AML, however, patients with Down syndrome have much better outcomes than non–Down syndrome children, with a >80% long-term survival rate. After induction therapy, these patients receive therapy that is less intensive to achieve better results.

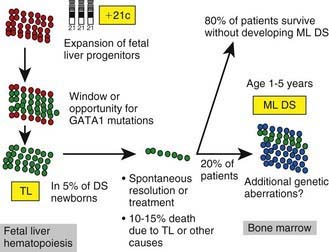

Approximately 10% of neonates with Down syndrome develop a transient leukemia or myeloproliferative disorder characterized by high leukocyte counts, blast cells in the peripheral blood, and associated anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly. These features usually resolve within the first 3 mo of life. Although these neonates can require temporary transfusion support, they do not require chemotherapy unless there is evidence of life-threatening complications. However, patients who have Down syndrome and who develop this transient leukemia or myeloproliferative disorder require close follow-up, because 20-30% will develop typical leukemia (often acute megakaryocytic leukemia) by 3 yr of life (mean onset, 16 mo). GATA1 mutations (a transcription factor that controls megakaryopoiesis) are present in blasts from patients with Down syndrome who have transient myeloproliferative disease and also in those with leukemia (Fig. 489-5 and see Table 489-5). Transient myeloproliferative disease also can occur in patients who do not have phenotypic features of Down syndrome. Blasts from these patients might have trisomy 21, suggesting a mosaic state.

Bercovich D, Ganmore I, Scott LM, et al. Mutations of JAK2 in acute lymphoblastic leukaemias associated with Down’s syndrome. Lancet. 2008;372:1484-1492.

Cushing T, Clericuzio C, Wilson C, et al. Risk for leukemia in infants without Down syndrome who have transient myeloproliferative disorder. J Pediatr. 2006;148:687-689.

Linabery AM, Olshan AF, Gamis AS, et al. Exposure to medical test irradiation and acute leukemia among children with Down Syndrome: a report from the children’s oncology group. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1499-e1508.

Mullighan CG, Collins-Underwood JR, Phillips LA, et al. Rearrangement of CRLF2 in B-progenitor- and Down syndrome–associated acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2009;41(11):1243-1246.

Zwaan MC, Reinhardt D, Hitzler J, et al. Acute leukemias in children with Down syndrome. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;5:53-70.

489.4 Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec), an agent designed specifically to inhibit the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase, has been used in adults and has shown an ability to produce major cytogenetics responses in >70% of patients (see Table 488-1). Experience in children suggests it can be used safely with results comparable to those seen in adults. While waiting for a response with imatinib, disabling or threatening signs and symptoms of CML can be controlled during the chronic phase with hydroxyurea, which gradually returns the leukocyte count to normal. Prolonged morphologic and cytogenetic responses are expected, but the opportunity for cure is enhanced by HLA-matched family donor allogeneic stem cell transplant, with up to 80% of children achieving a cure.

Kantarjian H, Giles F, Wunderle L, et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant CML and Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2542-2550.

Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Hochhaus A, et al. Dasatinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2260-2270.

Kolb EA, Pan Q, Ladanyi M, et al. Imatinib mesylate in Philadelphia chromosome–positive leukemia of childhood. Cancer. 2003;98:2643-2650.

Saglio G, Kim DN, Issaragrisil S, et al. Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2251-2256.

Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome–positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2531-2540.

489.5 Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia

Woods WG, Barnard DR, Alonzo TA, et al. Prospective study of 90 children requiring treatment for juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:434-440.

Yoshimi A, Kojima S, Hirano N. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, and management considerations. Paediatr Drugs. 2010;12:11-21.