19 The leg, ankle, and foot

In the orthopaedic out-patient clinic disorders of the foot are second in frequency only to disorders of the back. Their prevalence may have several causes. Hereditary factors: The foot is probably in a state of relatively rapid evolution consequent upon man’s assumption of the upright posture, and perhaps for that reason it is prone to variations in structure and form which may impair its efficiency. Postural stresses: Overweight throws an increased burden on the feet, and they may be unable to withstand the stress without ill-effect, especially if the intrinsic muscles are poorly developed. Footwear: The wearing of shoes is a potent cause of foot disorders. Many types of shoe interfere seriously with the mechanics of the foot, and the ladies’ shoe with high heel and pointed toe is particularly to blame.

SPECIAL POINTS IN THE INVESTIGATION OF LEG, ANKLE, AND FOOT COMPLAINTS

Steps in clinical examination

A suggested plan for the routine clinical examination of the leg, ankle, and foot is summarised in Table 19.1.

Table 19.1 Routine clinical examination in suspected disorders of the leg, ankle, and foot

| 1. LOCAL EXAMINATION OF THE LEG, ANKLE, AND FOOT | |

| Inspection | At the toes: |

| Bone contours and alignment | Flexion |

| Soft-tissue contours | Extension |

| Colour and texture of skin | |

| Scars or sinuses | Power (tested against resistance of examiner) |

| Palpation | Each muscle group to be tested in turn. (Power of calf muscles is best tested with the patient recumbent and then standing) |

| Skin temperature | |

| Bone contours | |

| Soft-tissue contours | (Compare with other side) |

| Local tenderness | Stability |

| State of peripheral circulation | Integrity of ligaments—particularly the lateral ligament of the ankle |

| Dorsalis pedis pulse | |

| Posterior tibial pulse | Appearance of foot on standing |

| Popliteal pulse | Colour |

| Femoral pulse | Shape of longitudinal arch |

| ? Cyanosis of foot when dependent | Shape of forefoot |

| Movements (active and passive, compared with normal side) | Efficiency of toes |

| At the ankle: | Efficiency of calf muscles (? ability to raise heel from ground while standing on affected leg alone) |

| Plantarflexion | |

| Extension (dorsiflexion) | Gait |

| At the subtalar joint: | |

| Inversion-adduction | Condition of footwear |

| Eversion-abduction | Sites of greatest wear. (Compare with other side) |

| At the midtarsal joint: | |

| Inversion-adduction | |

| Eversion-abduction | |

| 2. GENERAL EXAMINATION | |

| General survey of other parts of the body. The local symptoms may be only one manifestation of a widespread disease | |

Assessing the state of the peripheral circulation

Clinical assessment. This is based on a study of the texture of the skin and nails, colour changes, skin temperature, the arterial pulses, auscultation, and exercise tolerance. Texture of skin and nails: The skin of an ischaemic foot loses its hair and becomes thin and inelastic. The nails are coarse, thickened and irregular. Ulceration of the tips of the toes may be noted. Colour changes. A brick-red rubor or cyanosis occurring when the foot is made dependent after a period of elevation (Buerger’s test) denotes serious impairment of the arterial circulation. Temperature: A foot with impaired arterial supply is colder than normal, but little reliance can be placed on this test as applied clinically at the bedside. Arterial pulses: The pulses to be felt for are the dorsalis pedis, the posterior tibial, the popliteal and the femoral. The popliteal pulse is often difficult to feel even in normal individuals. Palpation should be made with the fingertips of both hands supporting the slightly flexed knee. Pulsation of the dorsalis pedis artery is best felt at the dorsum of the foot between the bases of the first and second metatarsals. The posterior tibial artery is felt about 2 cm behind and below the tip of the medial malleolus. Absence or impairment of arterial pulsation is an important sign of defective circulation. It should be remembered, however, that a normal pulse is easily masked by thickening or oedema of the soft tissues. Capillary return: In limb ischaemia capillary return is slowed after blanching of a digital pulp or nail by pressure. Auscultation: A bruit over one of the major limb vessels, caused by turbulence of blood flow, may denote partial obstruction or an arterio-venous communication.

Special investigations. These may be indicated when the clinical examination shows evidence of vascular impairment. They include ankle blood pressure recordings, Doppler ultrasound probe analysis, combined probe analysis and ultrasonography, pulse volume recording (plethysmography), and digital arteriography. For more detail on these and the treatment of limb ischaemia readers should consult a textbook of vascular surgery.

Movements at the ankle and tarsal joints

Ankle movement. The ankle is strictly a hinge joint. The only movements are extension (dorsiflexion) and plantarflexion. The range should be judged from the excursion of the hindfoot rather than the forefoot, so that any contribution from the tarsal joints is disregarded. Similarly, in testing the passive range, the foot should be controlled from the heel (Fig. 19.1). The normal range of ankle movement varies in different subjects; so the normal ankle must be used as a control. An average range is about 25° of extension (dorsiflexion) and 35° of plantarflexion.

In clinical examination the range of movement contributed by each component can be determined separately. To test subtalar movement support the lower leg by a hand gripping the ankle. With the other hand lightly grasp the calcaneus from below (Fig. 19.2). Instruct the patient alternately to invert and evert the foot, observing the range through which the heel rocks from side to side. Compare with the sound foot. The normal range is about 20° on each side of the neutral position.

To test midtarsal movement grasp the calcaneus firmly so that subtalar movement is eliminated. With the other hand lightly grasp the midfoot near the bases of the metatarsals (Fig. 19.3). Instruct the patient alternately to twist the foot inwards and outwards into inversion and eversion, and compare the range with that on the sound side. The normal is a rotation of about 15° on each side of the neutral position.

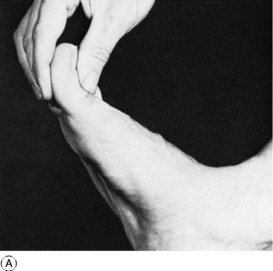

Toe movements. Determine the active and passive range at the metatarso-phalangeal and interphalangeal joints. It should be remembered that the normal range of dorsiflexion of the great toe at the metatarso-phalangeal joint is nearly 90° (Fig. 19.4). The range varies, but limitation to less than 60° of dorsiflexion is certainly abnormal. The range of downward flexion is about 15° but it varies between individuals. Movement at the lesser toes is variable: there should be not less than 30° of flexion at the metatarso-phalangeal joints and at the interphalangeal joints.

Examination of the feet under weight-bearing stress

Instruct the patient to stand evenly on both feet. Observe the general shape of the ankle, foot, and toes. Study the shape of the longitudinal arch. Is it of normal shape? Is it flattened so that the navicular region is in contact with the ground (pes planus or valgus)? Or is it higher than normal (pes cavus)? It is important to view the heel from the back, so that any inward (varus) or outward (valgus) deviation may be noted. Next study the forefoot. Is it splayed and broader than normal? Assess the function of the toes. Normally they can be pressed upon the ground by the action of the intrinsic muscles so that the metatarsal heads are lifted up and relieved of weight-bearing pressure. Finally, examine the efficiency of the calf muscles. The crucial test is to ask the patient to stand on the affected leg and to raise the heel from the ground (see Fig. 19.5).

Examination of spine

Certain deformities of the foot – especially pes cavus with clawing of the toes – may be caused by a neurological abnormality in the thoraco-lumbar or lumbar region of the spine, associated with spina bifida or other developmental anomaly (see p. 171). Examination should therefore be made for a tell-tale dimple, pigmented area, or tuft of hair on the overlying skin.

Footwear

The examination of the foot is not complete until the patient’s shoes have been inspected and compared on the two sides. Note the position of greatest wear. When the foot is normal the greatest wear in the sole occurs beneath the ball of the foot and slightly to the medial side. In the heel it is at the posterior border slightly to the lateral side. The state of the uppers is also important: excessive bulging on the medial side suggests a valgus foot and excessive bulging on the lateral side an inverted foot.

Radiographic examination

When laxity of the lateral ligament is suspected a special inversion film is required. This is an antero-posterior projection taken while the heel is held in fullest inversion by an assistant. If the lateral ligament is torn or lax the talus will then be shown tilted in the ankle mortise (see Fig. 19.10, p. 433).

DISORDERS OF THE LEG

RUPTURE OF THE CALCANEAL TENDON

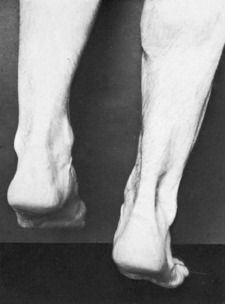

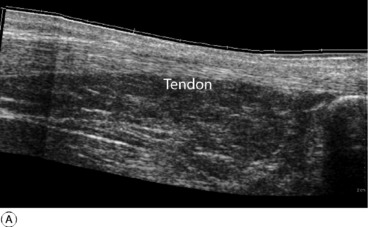

Diagnosis. The retention of some power of plantarflexion may deflect the unwary from the correct diagnosis. The crucial test is to ask the patient to lift the heel from the ground while standing only upon the affected leg (Fig. 19.5). This is impossible if the tendon is ruptured. In cases of doubt the gap in the tendon may be well demonstrated by ultrasound or MRI scanning (Fig. 19.6).

In the majority of younger patients, particularly those who wish to continue athletic pursuits after healing, operative treatment is preferable. It entails repair of the tendon, using non-absorbable sutures of synthetic material, tension on the suture line being relaxed by immobilising the limb with right-angled knee flexion and moderate ankle plantarflexion for 2 weeks. For the next four weeks a below-knee plaster with the ankle at 90° is worn. Certain protocols allow earlier mobilisation of the ankle under close supervision of a physiotherapist.

ACUTE OSTEOMYELITIS (General description of acute osteomyelitis, p. 85)

The pathological and clinical features and treatment conform to the general description on page 89.

CHRONIC OSTEOMYELITIS (General description of chronic osteomyelitis, p. 90)

Brodie’s abscess. This rather uncommon lesion was described on page 92. It is a special form of chronic osteomyelitis which arises insidiously, without a recognised acute infection preceding it. The tibia is the commonest site (see Fig. 7.7, p. 93).

SYPHILITIC INFECTION OF THE TIBIA (General description of syphilitic osteitis, p. 95)

Although skeletal syphilis is now rare in Western countries, it still occurs in other parts of the world, and when it does occur the tibia is often the bone affected. The infection may take the form of a localised gumma or of diffuse osteoperiostitis (see Fig. 7.11A&B, p. 96). There is a gradually enlarging swelling, with moderate pain. It is important to bear the possibility of syphilis in mind, because the swelling is easily mistaken for a tumour.

TUMOURS OF BONE

Benign tumours (General description of benign bone tumours, p. 106)

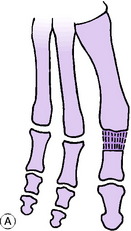

Chondroma

In the tibia or fibula this is seldom found except in multiple form in the condition of dyschondroplasia (p. 65). The individual tumours in this condition resemble enchondromata. They arise from the growing epiphysial cartilage plate, and they interfere with the normal growth of the bone. An important effect is that the growth of the tibia and fibula may be unequal, with the consequence that the bones may become curved or the plane of the ankle joint may be tilted away from the horizontal (see Fig. 6.4A, p. 65).

Malignant tumours (General description of malignant bone tumours, p. 112)

INTERMITTENT CLAUDICATION

Pathology. The basic disturbance is ischaemia of muscle, in consequence of which metabolites cannot be removed speedily enough when the muscle is exercised. The accumulation of metabolites is believed to be responsible for the pain, which subsides within a few minutes when the muscle is rested. The muscles usually affected are those of the calf, but in some instances other muscle groups are involved, according to the site of the arterial obstruction. The vascular lesion is usually a complete occlusion of the femoral or the popliteal artery. In claudication affecting the buttock the aortic bifurcation or the iliac artery may be occluded.

On examination there is objective evidence of impaired arterial circulation in the lower limb (p. 421). The posterior tibial, dorsalis pedis, and popliteal pulses are absent. There may be ischaemic changes in the skin of the foot. Evidence of widespread arterial or cardiac disease is nearly always found on general examination.

DISORDERS OF THE ANKLE

PYOGENIC ARTHRITIS OF THE ANKLE (General description of pyogenic arthritis, p. 96)

Pyogenic arthritis of the ankle is uncommon. The organisms reach the joint through the blood stream or through a penetrating wound; local spread from a focus of osteomyelitis of the tibia or fibula is rare because the bony metaphyses are entirely extra-capsular (see Fig. 7.2, p. 87).

TUBERCULOUS ARTHRITIS OF THE ANKLE (General description of tuberculous arthritis, p. 98)

Treatment. Early conservative treatment (p. 102) may restore a mobile ankle, but if in a resistant case articular cartilage is badly eroded or destroyed arthrodesis may have to be undertaken.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS OF THE ANKLE (General description of rheumatoid arthritis, p. 134)

One or both ankles are often affected by rheumatoid arthritis in common with other joints in the lower limb, particularly the foot. There may be marked destruction of the articular cartilage and subchondral bone with pain, stiffness, and deformity (Fig. 19.7).

Treatment. Medical treatment is along the lines suggested for the disease as a whole (p. 137). Local treatment: In the active phase rest in a plaster is sometimes required, but in most cases the patient should be encouraged to remain active as far as possible, with such help as may be gained from local support by a moulded polypropylene splint. Operation is advised mainly when destruction of articular cartilage has led to intractable pain with marked impairment of capacity for walking. Arthrodesis and replacement arthroplasty are the methods available. Arthrodesis is usually the operation of choice because it gives permanent relief of pain with good function. If the subtalar and midtarsal joints are also severely affected they should be included in the fusion. Replacement arthroplasty of the ankle is appropriate in some patients (Fig. 19.8). The operation is technically demanding because of the limited surgical access to the joint, while the long-term results are much less satisfactory than with the hip or knee because poor bone support may lead to early implant loosening.

OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE ANKLE (General description of osteoarthritis, p. 140)

Clinical features. The symptoms are pain which slowly increases over months and years, and limp. On examination the joint is a little thickened from hypertrophy of bone (osteophyte formation) at the joint margins. Movements are restricted slightly or severely according to the degree of arthritis.

Radiographs show the typical features of osteoarthritis – narrowing of the cartilage space, a tendency to sclerosis of the bone adjacent to the joint, and osteophyte formation at the joint margins (Fig. 19.9).

Surgical treatment should usually be by arthrodesis, which provides a painless stable joint for many years. A number of different methods are available to produce reliable bony fusion and with the introduction of arthroscopic techniques to remove the degenerate cartilage, combined with rigid internal fixation across the opposed bone surfaces, the post-operative rehabilitation is rapid. Unfortunately, after 10–15 years more than 50% of these patients develop further disability from hindfoot pain because of the accelerated onset of arthritis in the adjacent sub-talar and talo-navicular joints. In an attempt to overcome this problem in younger patients, replacement arthroplasty with resurfacing prostheses has been explored as a possible alternative (see Fig. 19.8). As with arthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis, the long-term results are still uncertain because of bone resorption and implant loosening and it is not yet widely recommended.

RECURRENT SUBLUXATION OF THE ANKLE

When the lateral ligament of the ankle is torn and fails to heal there may be persistent instability with recurrent attacks of giving way in which the talus tilts medially in the ankle mortise. Anterior displacement relative to the tibial articular surface may also occur. The causative injury is always a severe inversion force.

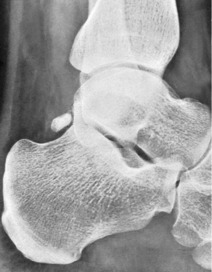

Radiographic features. Routine radiographs do not show any abnormality. Antero-posterior films must be taken while the heel is held fully inverted. If the lateral ligament is torn or lax the talus will then be shown tilted away from the tibio-fibular mortise at the lateral side through 20 or 30° or more (Fig. 19.10). Anterior displacement of the talus relative to the tibial articular surface may sometimes also be demonstrated in lateral radiographs taken while the foot is pushed forwards.

Treatment. If the disability is slight it may be sufficient to strengthen the evertor muscles (mainly the peronei) by exercises, to enable them to control the ankle more efficiently. Stability may also be enhanced by broadening and ‘floating out’ the heel of the shoe. If the disability is severe operation is required. A new lateral ligament may be constructed either from the peroneus brevis tendon or from the peroneus tertius. Trials are also proceeding with the use of artificial ligaments, either as substitutes or as a means of promoting the growth of new ligamentous tissue.

DISORDERS OF THE FOOT

CONGENITAL CLUB FOOT (Talipes equino-varus)

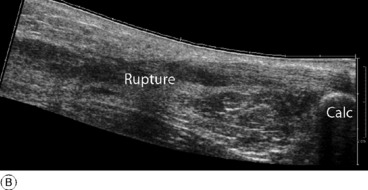

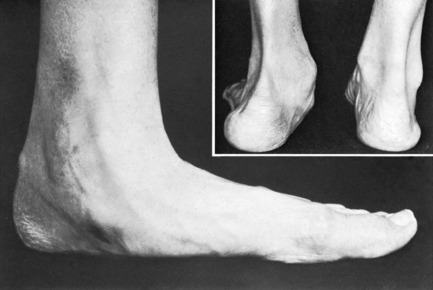

The rather vague term ‘club foot’ has come to be synonymous in the minds of most surgeons with the commonest and most important congenital deformity of the foot—talipes equino-varus (Fig. 19.11). The less common, and usually less serious, form of club foot, talipes calcaneo-valgus, will be considered later under that title.

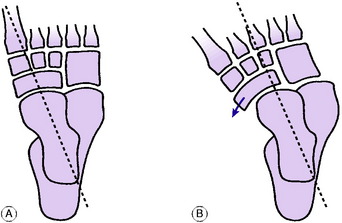

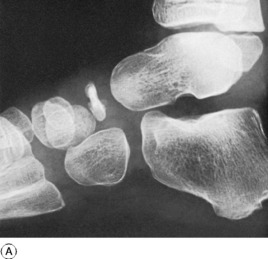

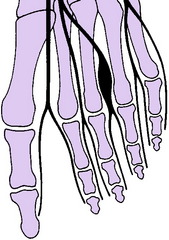

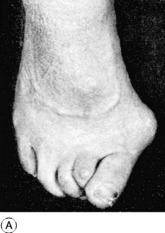

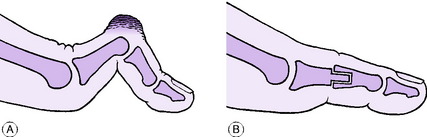

Pathology. The crucial component of the deformity is subluxation of the talo-navicular joint, so that the navicular bone lies partly on the medial aspect of the head of the talus instead of on its distal aspect (Fig. 19.12). The soft tissues at the medial side of the foot are under-developed and shorter than normal. The foot is adducted and inverted at the subtalar, midtarsal, and anterior tarsal joints, and is held in equinus (plantarflexion) at the ankle. In most cases under-development of the calf and peroneal muscles is a striking feature. Thus if only one foot is affected there is a marked discrepancy in the girth of the calf between the two sides.

In the absence of early effective treatment the developing tarsal bones assume an abnormal shape as growth occurs, perpetuating the deformity.

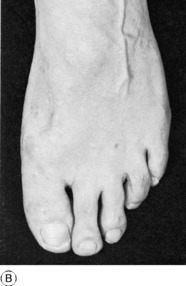

Clinical features. The deformity is much commoner in boys than in girls. (Contrast developmental dysplasia (congenital dislocation) of the hip, which is much commoner in girls.) One or both feet may be affected. When the infant is born it is noticed that the foot is turned inwards so that the sole is directed medially (Fig. 19.11). The deformity, to be more precise, consists of three elements:

Radiographic features. In the antero-posterior radiograph of a normal foot a line projecting the long axis of the talus forwards passes medial to the first metatarsal bone or coincides with it (Fig. 19.12A). In uncorrected or incompletely corrected club foot the line passes lateral to the metatarsal (Fig. 19.12B).

Treatment in a fresh case. Although it is seemingly a simple deformity, talipes equino-varus presents difficult problems in treatment. The most widely accepted practice is to rely upon conservative treatment by correction and splintage during the first year of life (often using the so-called Ponseti technique1) and often well beyond that; if casting and splintage fail to correct the position then operative correction is carried out.

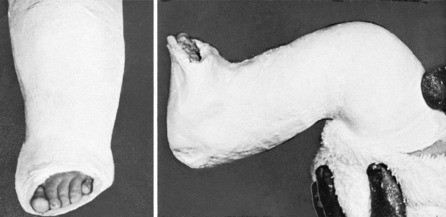

Correction of deformity. The deformity is corrected by firm manual pressure without anaesthesia (Fig. 19.13). The Ponseti technique involves first correcting the cavus deformity, then the adduction and heel varus, and finally the equinus deformity. Depending on the severity of the deformity, it may be possible to correct it fully by two or three manipulations, or as many as five or six manipulations at weekly intervals may be required.

Retention in a plaster is much to be preferred, because it holds the foot in the over-corrected position more efficiently and for a longer period than do metal splints or strapping – even though the technique of applying a plaster correctly is not easy to learn. The plaster must extend to the upper thigh, with the knee flexed 90° (Fig. 19.14); otherwise the infant is able to draw the foot up inside the plaster, with consequent loss of correction. The plaster must be changed every week at first, but the interval may be extended to two and then three weeks as the child grows larger.

Treatment in neglected or relapsed cases. Repeated manipulation and retention in plaster can produce worthwhile improvement in children of up to two years of age. If significant deformity is still present after the age of two, operative treatment is required. It should be appreciated that in these late cases no method of treatment – whether conservative or operative – is capable of restoring the foot to normal. The most that can be done is to restore a plantigrade foot.1

CONGENITAL TALIPES CALCANEO-VALGUS

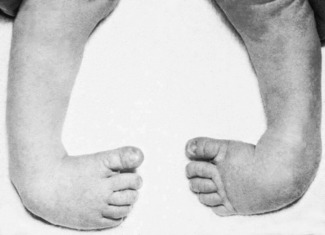

Clinical features. One foot or both feet may be affected. The foot rests in a position of eversion and dorsiflexion, so that its dorsum lies almost in contact with the shin (Fig. 19.15). Tightness of the dorso-lateral soft tissues prevents the foot from being brought down easily into inversion and equinus, though with steady pressure a fair degree of correction can usually be obtained.

If calcaneo-valgus deformity still persists when the child is a month old more intensive supervision is required. The surgeon should gently over-correct the deformity as far as possible by manipulation without anaesthesia, thereafter applying a plaster with the foot in the over-corrected position. The plaster is changed weekly until a full range of inversion and equinus is gained. At that stage the plaster may be discarded without fear of relapse.

ACCESSORY BONES IN THE FOOT

Many accessory bones have been described in the foot, but most are of little or no practical importance. The commonest is the os trigonum, which lies immediately behind the talus, on the upper surface of the tuberosity of the calcaneus (Fig. 19.16). It does not cause symptoms. It may be confused with a fracture of the talus.

The only tarsal accessory bone that is frequently responsible for symptoms is the os tibiale externum1 (accessory navicular bone) (Fig. 19.17). This lies medial to the navicular bone, and forms a well-marked prominence at the inner border of the foot which may become painful and tender from the pressure of the shoe. If the symptoms justify operation the accessory bone should be removed.

PES CAVUS

In pes cavus or ‘hollow foot’ the longitudinal arch of the foot is accentuated.

Cause. In many cases the deformity has a congenital basis. It is sometimes familial. In other cases there is an underlying neurological disorder causing muscle imbalance. For instance, it is often associated with a minor degree of spinal dysraphism (p. 171), or it may follow poliomyelitis.

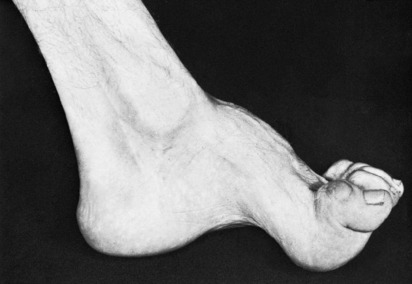

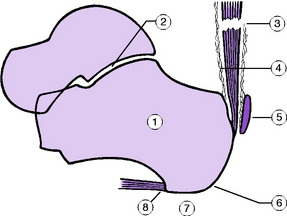

Pathology. The metatarsal heads are lowered in relation to the hind part of the foot, with consequent exaggeration of the longitudinal arch. The soft tissues in the sole are abnormally short, and eventually the bones themselves alter shape, perpetuating the deformity. There is always associated clawing of the toes, which are hyperextended at the metatarso-phalangeal joints and flexed at the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints (Fig. 19.18). This clawing seems to result from defective action of the intrinsic muscles – lumbricals and interossei. The effect is that the toes are almost functionless, and unable to take their normal share in weight-bearing. Consequently excessive weight falls upon the metatarsal heads on walking or standing, and hard callosities form in the underlying skin. The mal-alignment of the tarsal joints predisposes to the later development of osteoarthritis.

On examination the deformity is characteristic and easily recognised (Fig. 19.18). The longitudinal arch is high; the forefoot is thick and splayed; the toes are clawed; the metatarsal heads are prominent in the sole. Callosities beneath the metatarsal heads indicate that they take excessive weight. The toes cannot be straightened at will by the patient, nor can they be pressed firmly upon the ground to take a share in weight-bearing. There may also be tender callosities where the tops of the toes have rubbed against the shoes.

The base of the spine should be examined for a congenital anomaly such as spina bifida, which may be suggested by the presence of a dimple, a tuft of hair, or an area of pigmentation. If suspicion of spinal dysraphism exists radiographs of the spine should be obtained.

Operations on the tarsal joints. When osteoarthritis of the tarsal joints is the main cause of the symptoms arthrodesis of the affected joints – usually the subtalar, calcaneo-cuboid, and talo-navicular joints (the so-called triple arthrodesis) – is required. At the same time the deformity is corrected by excising a wedge of bone, base upwards, from the metatarsus. When necessary, this operation may be combined with operations to straighten the toes.

PES PLANUS (Flat foot; valgus foot)

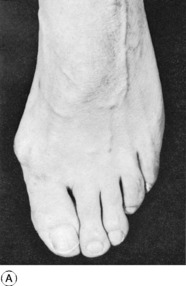

In this common condition the longitudinal arch of the foot is reduced so that, on standing, its medial border is close to, or in contact with, the ground (Fig. 19.19). It is usually associated with some degree of twisting outwards of the foot on its longitudinal axis (eversion or valgus deformity).

In adults, too, flat feet are often free from symptoms, but they are more liable than are normal feet to suffer foot strain (p. 444), and when pain is complained of it is usually from that cause.

Treatment. In children under 3 years old treatment is not required. In children over 3 the accepted method of treatment is to tilt the shoe slightly to the lateral side by inserting a wedge, base medially, between the layers of the heel (not the sole) (Fig. 19.20). This may help to overcome the valgus twist and to reduce the bulging-over of the uppers at the medial side, but it must be accepted that in most cases it is little more than a placebo. In older children it is better to insert a valgus insole (arch support) into the shoe, and this may be supplemented by a course of supervised exercises to strengthen the intrinsic muscles of the foot.

In cases of severe valgus deformity – which is usually the consequence of selective muscle imbalance, as after poliomyelitis – operation to restore the correct relationship between talus and calcaneus, and to fuse the two bones together (talo-calcaneal arthrodesis), may be considered. In children this operation may be done by placing bone grafts extra-articularly in the sinus tarsi, from the lateral side.

Peroneal spastic flat foot (spasmodic painful flat foot) and tarsal coalition

Treatment. If coalition is diagnosed early, excision of the abnormal bar may relieve pain and restore some mobility. In the later stages, if degenerative arthritis causes severe disability arthrodesis of the affected joints may be required.

OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE TARSAL JOINTS

Radiographs confirm the diagnosis and may give an indication of the primary underlying cause.

OSTEOCHONDRITIS OF THE NAVICULAR BONE (Köhler’s disease1)

The general subject of osteochondritis was discussed in Chapter 8 (p. 130). The growing navicular bone is one of its best-recognised sites. The developing nucleus of the bone is temporarily softened and usually becomes compressed by the mechanical forces entailed in walking. A disturbance of blood supply is possibly a causative factor, but the pathogenesis is not fully understood.

Pathology. The pathology is believed to be like that of osteochondritis of other growing bony nuclei (see Table 8.2, p. 131). The bone, presumably necrotic from ischaemia, loses its normal trabecular structure and may become fragmented as it is gradually absorbed and replaced by new living bone. After about two years the normal bone structure is restored and the bone may regain almost its normal size and shape. If slight deformation of the bone does remain, the growing foot seems to adapt itself to the altered shape and little or nodisability persists.

Radiographic features. Radiographs are diagnostic. The ossifying nucleus of the navicular bone appears squashed antero-posteriorly (Fig. 19.21A); it is denser than normal, and may have a fragmented appearance. Serial radiographs during the 2-year span of the disease show the gradual evolution of the bone changes. After a stage of maximal density and deformation a few months after the onset there is gradual improvement until normal bone texture is restored (Fig. 19.21B).

Treatment. Despite the slow evolution of the bone changes prolonged treatment is not required. Good results follow symptomatic treatment. Usually all that is necessary is to rest the foot for 6–8 weeks in a walking plaster.

PAINFUL HEEL

The causes of painful heel are conveniently classified according to the site of the pain (Fig. 19.22).

DISEASE OF THE CALCANEUS

Arthritis of the subtalar joint

The commonest type of arthritis in the subtalar joint is osteoarthritis secondary to fracture of the calcaneus (p. 444). The joint is occasionally subject to other forms of arthritis, such as pyogenic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculous arthritis, and gout.

Calcaneal paratendinitis (calcaneal tenosynovitis)

Clinical features. The patient is usually an active athletic young adult. There is pain in the region of the calcaneal tendon, made worse by activities such as running or dancing. On examination there is tenderness on palpation between finger and thumb deep to the tendon (Fig. 19.22), and there is slight local thickening in this region. The tendon itself is of normal size and consistency.

Treatment. Local physiotherapy may be helpful, particularly by the application of ultrasound therapy to the affected area, or from eccentric calf muscle training. In many cases relief is afforded by local injection of hydrocortisone deep to the tendon. (The tendon itself must not on any account be injected lest it be weakened, with serious risk of rupture.) In a resistant case operation may be required: it consists in excising the loose connective tissue surrounding and deep to the tendon.

Post-calcaneal bursitis

Clinical features. There is troublesome tenderness where the swelling is in contact with the shoe (Fig. 19.22). The symptoms are aggravated by walking, and they tend to be worse in winter than in summer; hence the term ‘winter heel’. On examination there is an obvious gristly prominence at the back of the heel; the overlying skin is thickened and may be red.

Calcaneal apophysitis (Sever’s disease1)

This harmless condition occurs only in children, during the period of active growth of the calcaneal apophysis. It was formerly believed to be an example of osteochondritis (p. 130), but it is now generally agreed that it is nothing more than a chronic strain at the attachment of the posterior apophysis of the calcaneus to the main body of the bone, possibly from the pull of the calcaneal tendon. It may thus be regarded as analogous to Osgood–Schlatter’s disease of the tibial tubercle (p. 415), and totally unrelated to osteochondritis.

Clinical features. The child, usually between 8 and 13 years old, complains of pain behind the heel, and a slight limp may be noticed. On examination there is tenderness over the lower posterior part of the tuberosity of the calcaneus (Fig. 19.22). Radiographs usually fail to show any alteration from the normal. Importance has sometimes been attached to an appearance of fragmentation of the calcaneal apophysis, but this is a normal state, often seen in children without pain in the heel.

Tender heel pad

Clinical features. Pain beneath the heel on standing or walking is the only symptom. On examination there is well-marked local tenderness on firm palpation over the heel pad (Fig. 19.22).

Plantar fasciitis

Pathology. The lesion affects the soft tissues at the site of attachment of the plantar aponeurosis to the inferior aspect of the tuberosity of the calcaneus (Fig. 19.22).

Treatment. Conservative treatment usually suffices if pursued energetically, though recovery may be slow. A course of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is usually prescribed. The heel should be protected by a resilient cushion on an insole. If these measures fail, local injection of hydrocortisone into the tender area may be tried. If the fasciitis is part of a widespread inflammatory disorder (notably Reiter’s syndrome) treatment appropriate to the underlying condition should be instituted.

PAIN IN THE FOREFOOT (METATARSALGIA)

Anterior flat foot (dropped transverse arch)

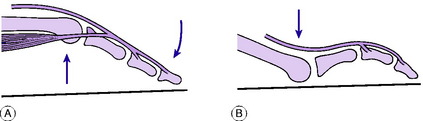

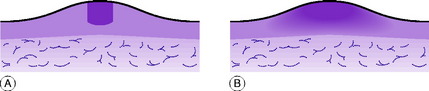

Pathology. Even in normal feet the transverse arch is only a potential arch, not a constant one. But in the normal state the metatarsal heads can be raised from the ground at will by the action of the toes, held straight at the interphalangeal joints by the intrinsic muscles and flexed strongly at the metatarso-phalangeal joints by the intrinsic muscles in conjunction with the long and short flexors (Fig. 19.23A). Thus the weight is shared between the metatarsal heads and the toes. If the intrinsic muscles are inefficient the toes are unable to fulfil their important weight-sharing function and all the pressure falls upon the metatarsal heads (Fig. 19.23B). The excessive pressure leads to the formation of callosities.

If disability is severe, pain from local prominence of an individual metatarsal head in the sole may be relieved by osteotomy of the neck of the metatarsal and dorsal displacement of the head.

Stress fracture of a metatarsal bone (march fracture; fatigue fracture)

Radiographs at first show only a faint hair-line crack which is easily overlooked (Fig. 19.24A), but after two or three weeks the callus surrounding the fracture is clearly visible and usually abundant (Fig. 19.24B).

Plantar digital neuritis (Morton’s metatarsalgia1; interdigital neuroma)

This condition, which is primarily an affection of a digital nerve, is characterised typically by metatarsal pain combined with a radiating pain in the third and fourth toes.

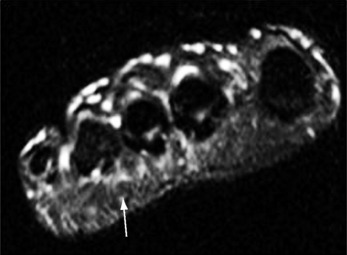

Pathology. The underlying lesion is a fibrous thickening or ‘neuroma’ of the digital nerve of the 3–4 cleft just proximal to its point of division into terminal branches. It takes the form of a fusiform swelling, usually about a centimetre long, surrounding the nerve as it lies in the space between the heads of the third and fourth metatarsals (Fig. 19.25). Occasionally the nerve to the 2–3 cleft is the one affected. The cause of the fibrous thickening is uncertain.

On examination the forefoot is often splayed, as in anterior flat foot. Sometimes a painful click can be elicited by compressing the metatarsal heads together from side to side, and upward pressure on the sole between the third and fourth metatarsal heads is painful.

Imaging. Plain radiographs are normal, but the abnormality of the nerve can be visualised with ultrasound or MRI scanning (Fig. 19.26) confirming the diagnosis.

PLANTAR WART (Verruca pedis; verruca plantaris)

Plantar warts may occur in any part of the sole of the foot, including the under surface of the heel. They are like warts elsewhere, except that they do not project beyond the skin surface. They are distinct from plantar callosities, which are simply localised thickenings of the skin at points of excessive pressure.

Cause. A virus infection is responsible.

Clinical features. The chief complaint is of severe localised pain on walking. On examination the skin surrounding the wart is thickened and therefore raised. The wart, a little darker in colour and with a mosaic surface, is seen in the centre of the raised area (Fig. 19.27). Its edge is clearly demarcated from the surrounding skin: this can be discerned easily if the skin is stretched away from the wart, when a tiny cleft becomes apparent between wart and skin. There is always marked local tenderness on pressure over the wart.

Diagnosis. The main difficulty is to distinguish warts from callosities. Warts occur anywhere on the sole, callosities only over points of pressure. Warts are also much more tender than callosities. But the most reliable distinguishing feature is that a wart has a mosaic surface and a clearly defined margin with a potential cleft between it and the skin (Fig. 19.28A), whereas a callosity blends imperceptibly with the surrounding normal skin (Fig. 19.28B).

CALLOSITIES

A callosity is simply a localised thickening of the skin in response to abnormal pressure. It is nearly always secondary to a pre-existing disorder of the foot.

Plantar callosities are callosities on the sole of the foot. They occur under a prominent bone. They are commonest beneath the metatarsal heads when deficient intrinsic muscles prevent the toes from taking their proper share in weight-bearing (anterior flat foot, p. 449). They are also common beneath the base of the fifth metatarsal in patients who for any reason walk with the foot inverted.

Callosities on the toes often take the form of localised thickenings, when they are termed corns. They are caused by pressure against the shoe, and they are especially common when the dorsum of a toe is made unduly prominent by a fixed flexion deformity, as in hammer toe (see Fig. 19.33A, p. 459).

DISORDERS OF THE TOES

HALLUX VALGUS

Cause. In some cases, particularly in children and adolescents, hereditary factors are responsible. But in most the deformity is caused by the toes being persistently forced laterally by enclosure in narrow pointed shoes. The wearing of high heels favours the development of hallux valgus because the forefoot is forced into the narrow pointed part of the shoe.

Pathology. Outward deviation of the great toe is the most obvious feature of the deformity, but a further, almost constant feature is that the first metatarsal is deviated medially, so that the gap between the heads of the first and second metatarsals is unduly wide (metatarsus primus varus). Indeed this may often be the primary defect. After several years two secondary changes occur. One is the formation of a thick-walled bursa (bunion) over the medial prominence of the metatarsal head; this may become inflamed, occasionally with suppuration. The second, a later development, is osteoarthritis of the metatarso-phalangeal joint consequent upon its mal-alignment (see Fig. 19.30B).

Clinical features. The patient is nearly always a woman, who is often at or past middle age when she seeks advice but may sometimes be a young woman or even an adolescent girl. The early symptoms arise from tenderness over the bunion from pressure against the shoe. There is also difficulty in getting comfortable footwear. Later, additional symptoms arise from osteoarthritis of the metatarso-phalangeal joint, and from flattening of the transverse arch (anterior flat foot, p. 449), which is a common associated deformity.

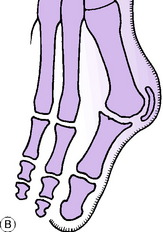

On examination the deformity is obvious at a glance (Figs 19.29A and 19.30A). The skin over the prominent joint is hard, reddened, and tender. Often a thick-walled bursa can be felt, and occasionally it is distended with fluid (Fig. 19.30B). In relatively early cases metatarso-phalangeal joint movements are free and painless, but in severe cases of many years’ duration the secondary osteoarthritis makes movement limited and painful. In late cases the forefoot is often flat and splayed, and the toes may be severely curled (Fig. 19.30A).

Treatment. In mild cases treatment is not required, but footwear must be selected with care to obtain adequate width. It may also be worthwhile to protect the bunion with pads of felt, and to wear a wedge of plastic foam between the great toe and the second toe to reduce the deformity.

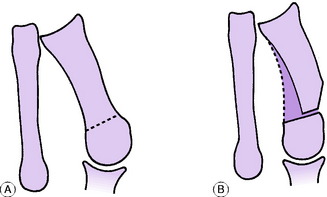

Displacement osteotomy of the neck of the first metatarsal bone. This is illustrated in Fig. 19.31. After division of the neck of the metatarsal the head fragment is displaced markedly laterally (Fig. 19.31B). The outward shift of the metatarsal head eliminates the prominence of the ‘exostosis’ without the need for its removal. The soft tissues between the heads of the first and second metatarsals are also relaxed, allowing permanent reduction of the subluxation at the first metatarso-phalangeal joint. After operation the toe may be immobilised in plaster for 6 weeks or fixed with a screw to ensure union at the site of osteotomy without loss of position.

By a process of remodelling, the alignment of the first metatarsal is gradually altered after operation so that it lies closer to the second metatarsal (Fig. 19.31B).

In this operation the joint itself is left undisturbed, indeed unopened. The operation gives good results in patients with relatively slight deformity (Fig. 19.29B): it does not shorten the toe appreciably or impair active movement, and it is therefore particularly suitable for young patients who wish to lead an energetic life.

Excision arthroplasty of the first metatarso-phalangeal joint by Keller’s1 method is widely used in elderly patients. The object is to create a flail, freely movable false joint between the first metatarsal and the proximal phalanx, with correction of the mal-alignment. This is done by excising the proximal half of the proximal phalanx so that a gap is left between the two bones: at the same time the bursa is excised and the medial prominence of the metatarsal head is smoothed off with a chisel (Fig. 19.32A).

The space created by excision of the base of the phalanx fills with rubbery fibrous tissue, and a false joint forms which allows a reasonable range of movement (Fig. 19.32B).

When severe hallux valgus in an elderly patient is associated with flattening of the transverse arch and marked clawing of the toes (see Fig. 19.30A), operation of any type may be disappointing and it may be wiser to rely upon well-made surgical shoes.

HAMMER TOE

The term hammer toe denotes a fixed flexion deformity of an interphalangeal joint.

Cause. Presumably an imbalance of the delicate arrangement of flexor and extensor tendons is responsible; but the precise explanation of its occurrence is unknown. Hammer deformity, especially of the second toe, is often associated with severe hallux valgus (see Fig. 19.30A).

Pathology. The proximal interphalangeal joint of the second toe is that most commonly affected. The affected joint is sharply angled into flexion. Secondary contracture of the plantar aspect of the joint capsule fixes the deformity, and a callosity usually forms over the dorsum of the flexed joint, from pressure against the shoe (Fig. 19.33A).

Clinical features. Typically the deformity affects only one toe – usually the second. In the characteristic deformity the proximal interphalangeal joint is in fixed flexion, and the distal interphalangeal joint, though still mobile, rests in compensatory hyperextension (Fig. 19.33A). The symptoms, if any, are caused by the overlying callosity or ‘corn’ or pain from bearing weight on the end of the toenail.

Treatment. If symptoms are slight the deformity may be accepted, or conservative treatment by protective felt pads may be sufficient. In severe cases operation gives gratifying results. The joint surfaces are excised and the joint is arthrodesed or pseudarthrosed in the corrected position (Fig. 19.33B).

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS OF THE TOE JOINTS

Deformity of the forefoot is a common cause of pain and disability in rheumatoid arthritis, but may be underdiagnosed because of the more visible problems in the patient’s other lower limb joints. Characteristically the metatarso-phalangeal joints are most affected, with destruction of articular cartilage, dorsal subluxation of the phalanges and clawing of the toes. Painful skin callosities then develop on the sole beneath the prominent metatarsal heads and on the dorsum of the flexed toes from the pressure of footwear.

In the early stages radiographs show only joint narrowing and marginal erosions. In the later stages there may be subluxation or dislocation of the metatarso-phalangeal joints with marked destruction of bone (Fig. 19.34).

OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE TOE JOINTS

In practice, osteoarthritis in the toes is seen commonly only in the metatarso-phalangeal joint of the great toe. This has been termed hallux rigidus. Occasionally the metatarso-phalangeal joint of one of the smaller toes is affected, usually as a late result of Freiberg’s disease of a metatarsal head (p. 462).

Hallux rigidus

Pathology. The changes are like those of osteoarthritis in other joints. The articular cartilage is gradually worn away from both surfaces of the joint until eventually the subchondral bone is exposed. The exposed bone becomes hard and glossy (eburnation). The marginal bone hypertrophies to form osteophytes, which often cause obvious thickening, especially at the dorsum of the toe.

Clinical features. The complaint is of pain in the base of the great toe on walking. On examination the metatarso-phalangeal joint is palpably thickened from osteophyte formation. If an osteophyte is especially prominent on the dorsal or medial aspect of the joint a thick-walled bursa (bunion) may form over it; occasionally the bursa is distended with fluid. Flexion and extension of the toe at the metatarso-phalangeal joint are restricted – usually markedly so by the time the patient seeks advice (Fig. 19.35A). Forced dorsiflexion of the painful joint on walking is the main source of the disability. (It should be remembered that the normal range of dorsiflexion at the metatarso-phalangeal joint of the great toe is nearly 90°.)

Radiographs confirm the presence of osteoarthritis. The cartilage space is narrowed, the subchondral bone tends to be sclerotic, and there is osteophytic spurring of the joint margins (Fig. 19.35B).

When the disability is severe operation should be advised. One method is to create a flail joint by excision of the base of the proximal phalanx (Keller’s arthroplasty), as for hallux valgus. Many surgeons find, however, that arthrodesis of the metatarso-phalangeal joint (see Fig. 4.1B) in a position of slight extension gives better results, with complete relief of pain.

GOUTY ARTHRITIS OF THE GREAT TOE JOINTS (General description of gouty arthritis, p. 143)

The joints of the great toe are those most often affected in gout, especially in the first attack.

Chronic gout. In this form deposits of sodium biurate in and around the joints of the great toe lead to persistent nodular thickening. Radiographs show rounded areas of transradiance in the bone ends; these represent deposits of sodium biurate (which is transradiant) in the subchondral bone.

Treatment. Acute attacks respond to selected non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as indometacin or naproxen, begun in high dosage which is reduced after two or three days, or to colchicine. Meanwhile the foot should be rested, and the toe should be protected from pressure by a bulky wool dressing. The treatment of recurrent and chronic gout was detailed on page 145.

FREIBERG’S DISEASE OF A METATARSAL HEAD1 (Metatarsal osteochondritis)

Freiberg’s disease of a metatarsal head is regarded by some as an example of osteochondritis juvenilis (p. 130) and by others as osteochondritis dissecans (p. 153). It may therefore be advisable to use the non-committal eponymous title for the present. The essential feature of Freiberg’s disease is partial necrosis and fragmentation of a metatarsal head, which may become deformed under the pressure of weight-bearing. It is an uncommon condition.

Pathology. The epiphysis of one of the metatarsal heads – nearly always the second or third – is the part affected. The bony nucleus becomes necrotic and granular. Part of the articular surface separates, usually remaining attached only by a hinge of articular cartilage. While it is in this crumbly state the metatarsal head is crushed by the pressure against it of the base of the proximal phalanx of the toe. The articular surface of the metatarsal head thus loses its normal dome-shaped contour and becomes flat (Fig. 19.36). After about 2 years the texture of the bone returns to normal, but flattening of the articular surface remains. Later, the distortion of the joint surface often leads to osteoarthritis.

Clinical features. At the time of onset the patient is 14 to 17 years old. There is pain in the affected metatarso-phalangeal joint, worse on standing or walking. On examination there is slight thickening in the region of the head of the metatarsal, which is tender on pressure. Movements of the metatarso-phalangeal joint are slightly restricted and painful. Radiographs reveal the nature of the trouble, though at first the changes are very slight and may be overlooked. Later the head of the metatarsal appears fragmented, with patches of increased density. Finally, the articular surface is flattened, so that the end of the bone appears square-cut instead of round (Fig. 19.36).

Treatment. When the diagnosis can be made in the early stage – before marked radiographic changes are apparent – operation offers a hope of preventing permanent distortion of the joint surface. Through a window cut in the dorsal surface of the metatarsal neck the necrotic bone of the head is curetted out and replaced by cancellous chip bone grafts, packed firmly enough to restore the normal dome-shaped contour of the articular surface. Thereafter the toe is supported in a plaster cuff for 6 weeks.

INGROWING TOE NAIL (Embedded toe nail)

Ingrowing toe nail is common only in the great toe.

When the nail is cut its sides should be left long enough to project beyond the terminal pulp (Fig. 19.37A): if it is cut too short a sharp corner of nail lies in contact with the lateral skin fold (Fig. 19.37B), and this corner may tend to embed itself in the skin, especially if there is local pressure at the side of the toe. In the presence of dirt and sweat, infection is then liable to arise.

Clinical features. The lesion may be at the medial or (more commonly) the lateral border of the nail, or both. There is pain at the affected anterior corner of the nail. On examination the skin fold is inflamed, and there may be local suppuration where the corner of the nail digs into the skin.

Treatment. In mild cases conservative treatment may suffice. Pledgets of gauze soaked in alcohol (surgical spirit) are tucked beneath the corner of the nail twice a day, and the nail is allowed to grow until its edges project beyond the skin folds (Fig. 19.37A).

In long-standing cases operation is advisable. If only one side of the nail is involved it is sufficient to avulse a strip of nail at the affected side and then to prevent re-growth of this part. Since the nail is formed only from the germinal matrix – the proximal curved segment of the nail bed that corresponds to the lunula – and not from the nail bed as a whole, it is necessary to remove only an appropriate piece of the germinal matrix to prevent regrowth (Fig. 19.37C).

In the worst cases, with infection at both sides of the nail, permanent ablation of the entire nail by excision of the whole of the germinal matrix is more satisfactory (Fig. 19.37D). The small raw area that remains can be covered simply by advancing a dorsal skin flap, based proximally and with its free edge at the nail fold.

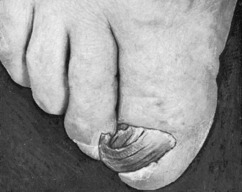

ONYCHOGRYPOSIS

Translated from the Greek, this means ‘hooked nail’. The term is descriptive. The nail – usually of the great toe – is enormously thickened, discoloured and curved, eventually resembling a miniature ox-horn (Fig. 19.38). The condition is due to a chronic fungal infection of the nail.

Treatment. Simple removal of the nail is an adequate temporary measure; but the new nail will become similarly deformed. The chance of this is reduced with appropriate oral antifungal therapy. For permanent cure the nail bed must be ablated by excision of the germinal matrix, as described in the section on ingrowing toe nail (p. 464).

1 Ignacio Ponseti (1914–) Spanish born orthopaedic surgeon emigrated to Iowa in USA in 1941 and developed his innovative conservative treatment for clubfoot, which he still teaches and is widely used throughout the world.

1 Plantigrade = sole walking; with the sole on the ground.

1 The term os tibiale externum may seem confusing in so far as the ossicle is on the inner side of the foot. The title however relates to the embryonic position of the foot, in which the ossicle forms on the outer side.

1 Alban Köhler (1874–1947) German pioneer in radiology worked in Wiesbaden and described the condition in 1908.

1 James Sever (1878–1964) American orthopaedic surgeon who was Chief at Boston Children’s Hospital for 40 years and described the condition in 1912. He also wrote articles on neonatal brachial plexus injuries.

1 Thomas Morton (1835–1903) American Civil War surgeon and founder of Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital described the condition in 1876.

1 Albert H. Freiberg (1868–1940) American orthopaedic surgeon worked throughout his career in Cincinnati, Ohio. He described the condition, which he described as an infarction from local trauma, in 1914.