Chapter 669 The Knee

Normal Range of Motion

Knee pain is one of the most common presenting complaints in older children and adolescents. This is commonly related to trauma but may also be insidious in onset. Knee effusion may be a common feature associated with knee pain. Depending on the etiology of the intra-articular process, the fluid collected in the knee may be blood (trauma- or hemophilia-induced hemarthrosis), inflammatory fluid (juvenile rheumatoid arthritis), or purulent material (septic arthritis). The presence of fat globules in the blood aspirated from a hemarthrosis suggests an occult fracture. Recurrent effusions can indicate a chronic internal derangement such as a meniscal tear. Aspiration of the joint fluid is often necessary to establish the diagnosis as well as to offer relief of symptoms (Chapter 684).

669.1 Discoid Lateral Meniscus

Treatment

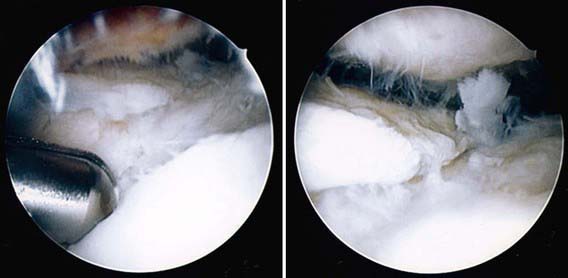

Many children with discoid menisci require no treatment. These children should be followed and treated only if pain or loss of motion occurs. Surgery may be considered when DLM leads to locking, swelling, loss of motion, inability to run, or inability to participate in sports. The treatment is to excise tears and reshape the meniscus arthroscopically (Fig. 669-1). Meniscal instability can occasionally be repaired or reconstructed. Complete excision may be necessary if other procedures are unsuccessful.

669.3 Osteochondritis Dissecans

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

MRI is helpful in determining the integrity of the articular cartilage and stability of the lesion. Arthroscopy is the most reliable method of evaluating the status of the lesion (Fig. 669-2). Factors commonly associated with a good prognosis are younger age group, small lesion, non–weight-bearing location, and no displacement. Four stages are involved with the progression of osteochondritis dissecans. Stage I consists of a small area of subchondral compression; stage II consists of a partially detached fragment; in stage III, the fragment is completely detached but remains in the crater; and by stage IV, the fragment is loose in the joint.

Ganley TJ, Kolze EA, Gregg JR. Pediatric sports medicine. In: Dormans JP, editor. Pediatric orthopedics and sports medicine: the requisites in pediatrics. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004:138-158.

Kocher MS, DiCanzio J, Zurakowski D, et al. Diagnostic performance of clinical examination and selective magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of intraarticular knee disorders in children and adolescents. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:292-296.

669.4 Osgood-Schlatter Disease

Radiographs are usually the only diagnostic studies necessary (Fig. 669-3). Fragmentary ossification of the tibial tubercle is noted in some cases, which is often a normal variant. Some cases are associated with patella alta.

Figure 669-3 Lateral radiograph of the knee demonstrating apophysitis of the tibial tubercle in Osgood-Schlatter disease.

Bensahel H, Souchet P, Pennecot GF, et al. The unstable patella in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;9:265-270.

Davids JR. Pediatric knee: clinical assessment and common disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1996;43:1067-1090.

Ganley TJ, Kolze EA, Gregg JR. Pediatric sports medicine. In: Dormans JP, editor. Pediatric orthopedics and sports medicine: the requisites in pediatrics. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004:138-158.

Ganley TJ, Lou JE, Pryor K, et al. Sports medicine. In: Dormans JP, editor. Pediatric orthopedics and sports medicine: the requisites in pediatrics. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004:273-298.

Hamer AJ. Pain in the hip and knee. BMJ. 2004;328:1067-1069.

Herring JA. Disorders of the knee. In: Herring JA, editor. Tachdjian’s pediatric orthopedics. ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:789-837.

669.5 Idiopathic Adolescent Anterior Knee Pain Syndrome

Davids JR. Pediatric knee: clinical assessment and common disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1996;43:1067-1090.

Ganley TJ, Lou JE, Pryor K, et al. Sports medicine. In: Dormans JP, editor. Pediatric orthopedics and sports medicine: the requisites in pediatrics. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004:273-298.

Hamer AJ. Pain in the hip and knee. BMJ. 2004;328:1067-1069.

Herring JA. Disorders of the knee. In: Herring JA, editor. Tachdjian’s pediatric orthopedics. ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:789-837.

Stanitski CL. Instructional course lecture: anterior knee pain syndromes in the adolescent. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1407-1416.

669.6 Patellar Subluxation and Dislocation

Sillanpää PJ, Mattila VM, Mäenpää H, et al. Treatment with and without initial stabilizing surgery for primary traumatic patellar dislocation. A prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(2):263-273.

Vahasarja V, Kinnunen P, Lanning P, et al. Operative realignment of patellar malalignment in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:281-285.