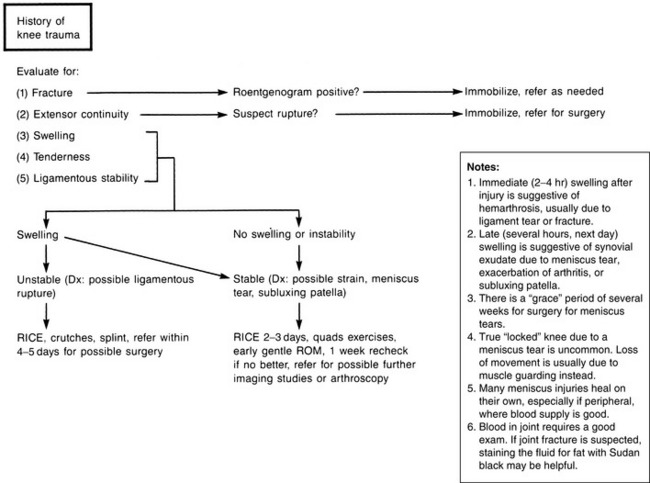

Chapter 11 The Knee

The knee is the largest joint in the body. The lower portion of the femur and upper aspect of the tibia articulate at only two points where the rounded femoral condyles bear weight on the flat tibial plateaus. The knee joint is subject to a wide variety of traumatic, mechanical, and inflammatory disorders.

Anatomy

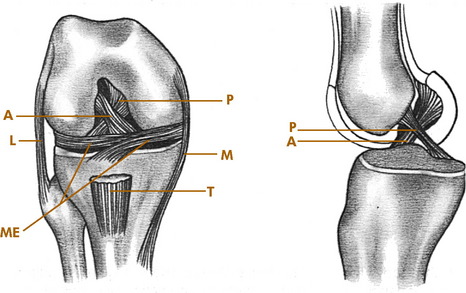

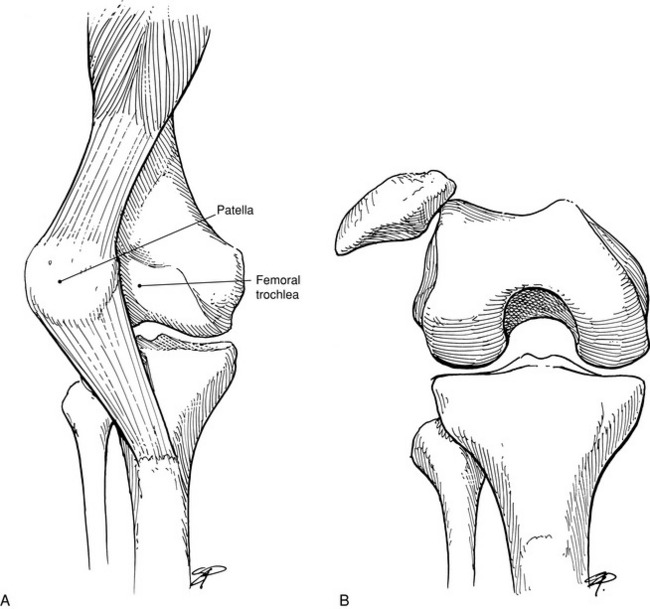

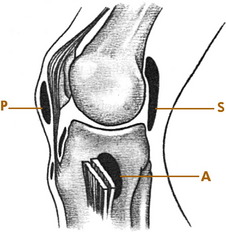

The knee joint consists of medial and lateral, femoral and tibial condyles; and the patella. It is essentially a round bone sitting on a flat bone with no intrinsic bony stability and depends completely on its ligaments, muscles, menisci, and capsule for support. The most important ligaments of the knee are the medial and lateral collateral ligaments (LCLs) along with their associated posterior capsular structures and the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (Fig. 11-1). The medial collateral ligament originates below the adductor tubercle and attaches to the upper medial tibia. It limits abduction and assists in controlling rotation. The LCL attaches to the lateral epicondyle of the femur and head of the fibula and controls adduction. The cruciate ligaments attach to the intraarticular portions of the femur and tibia. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) prevents anterior displacement of the tibia and helps control rotation of the tibia on the femur. The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) prevents backward displacement of the tibia on the femur.

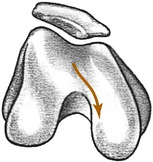

Normal knee motion consists of a combination of rotation and either extension or flexion. Normally, as the knee flexes, the tibia internally rotates. Extension of the knee is accompanied by lateral or external rotation of the tibia. These rotational motions are controlled by the ligaments and menisci of the knee. This rotation is reflected in the course that the patella takes with flexion and extension movements (Fig. 11-2). Thus, damage to the knee (such as a torn meniscus, which prevents normal tibial rotation) can cause patellar symptoms resulting from abnormal patellar excursion. These patellar symptoms are typically aggravated by walking up and down stairs, an activity that puts the greatest strain on the patella and knee extensors.

Roentgenographic Anatomy

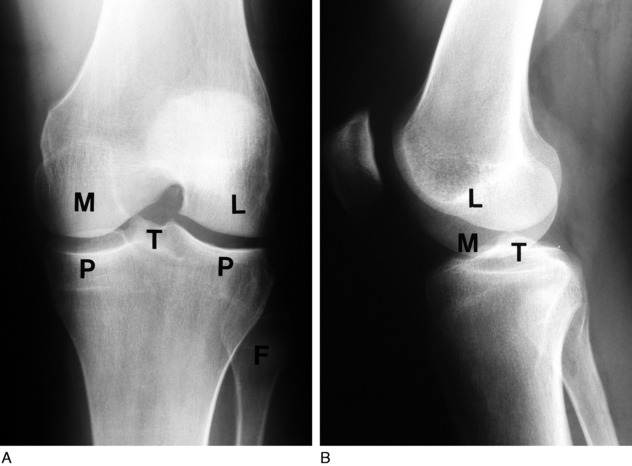

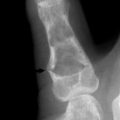

Anteroposterior and lateral views are essential in the diagnosis of knee disorders (Fig. 11-3). A tunnel view visualizes the intercondylar notch, and tangential views are helpful in diagnosing patellar disorders. With patients over the age of 40, the anteroposterior view should always be performed with the patient standing. This may reveal subtle joint space narrowing if osteoarthritis is present.

Lesions of the Meniscus

INJURIES OF THE MENISCUS

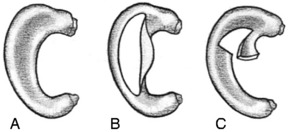

The menisci, or semilunar cartilages, are two C-shaped structures composed of fibrocartilage that help act as cushions between the femur and tibia. They also assist in the control of normal knee motion. If the normal rotation of the tibia is forcibly prevented as the knee is flexed or extended (that is, if flexion occurs with external rotation or extension occurs with internal rotation), a tear in the meniscus can occur. The injury may be isolated or in conjunction with ligamentous ruptures. Meniscus tears are the most common of all knee injuries, and the pathologic characteristics of the tear are variable (Fig. 11-4). When an injury occurs that produces free fragments or tears, healing to the main body of the meniscus may not take place. The fragment often remains permanently detached but viable because nourishment for the meniscus is provided by the joint fluid. This joint fluid circulates around the tear and often prevents healing from taking place. Persistent symptoms are the result. The medial meniscus is injured 10 times more frequently because it is more firmly attached and less mobile than the lateral meniscus. In long-standing disease, articular cartilage erosion of the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joints may even result.

FIG. 11-4 A, Normal meniscus. B, Longitudinal, or “bucket-handle,” tear. C, Tear of the posterior horn.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The examination usually reveals a joint effusion (Fig. 11-5). Its presence indicates acute or chronic synovial irritation. Its absence by history or examination should cause another diagnosis to be considered. This fluid may cause the patella to be ballotable. A click may also be present when the patella is pressed against the femur.

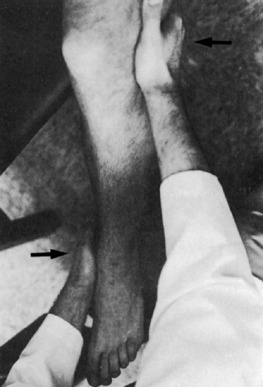

Pain and tenderness at the joint line either medially or laterally may be present. The range of motion is frequently limited. This may be caused by swelling, pseudolocking, or occasionally the interposition of the torn meniscus. In long-standing disease, atrophy of the quadriceps muscle, especially the vastus medialis, occurs rapidly (Fig. 11-6).

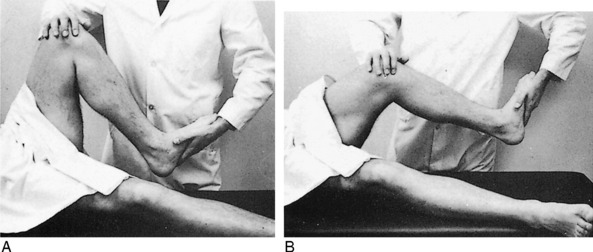

The McMurray test is sometimes helpful in detecting a meniscus tear, although it is difficult to perform on a painful, swollen knee, and the results are often inconsistent (Fig. 11-7). Full knee flexion, which increases pressure on the posterior horns, may cause pain with many meniscus tears.

SPECIAL STUDIES

TREATMENT

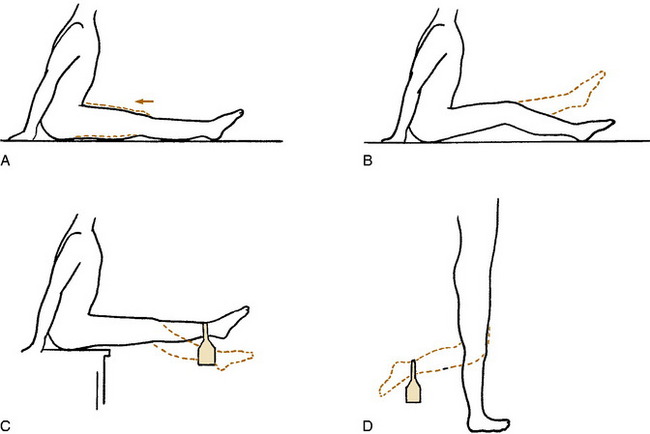

The initial treatment is conservative, except for those rare cases in which the knee is truly locked. Many meniscus tears, especially peripheral ones, can heal spontaneously in a few weeks. A bulky compression dressing (often called the “Robert Jones” dressing) and ice are applied if the injury is acute, and the knee is elevated (Fig. 11-8). The patient is placed on crutches and started on quadriceps-strengthening exercises (Fig. 11-9). These exercises will help compress out the joint effusion and maintain strength, and they should always be performed with the knee near complete extension to prevent patellofemoral pain from developing. Gentle range-of-motion exercises are started in 2 to 3 days. Swimming is an excellent exercise for increasing motion and decreasing discomfort. As pain subsides and motion returns, weight-bearing activities are gradually resumed, but quadriceps exercises are continued for 2 to 4 weeks. There are few indications for aspiration of the knee and even fewer indications for the injection of steroids in the treatment of an acute injury. The protective responses of the patient should be maintained, and it is better to reduce swelling by quadriceps contractions and to rehabilitate the knee through exercises.

Comments

Meniscal “tears” are common in conjunction with osteoarthritis of the knee, and if the two disorders occur together, which they often do, it is virtually impossible to determine whether the meniscal abnormality is the source of pain. This calls into question the usefulness of MRI (and meniscal surgery) in the older patient who already has degenerative disease on plain films. The likelihood of finding a meniscal tear in the presence of moderate osteoarthritis is almost 90%, and MRI probably adds very little to the decision-making process in these patients. Decisions regarding the usefulness of meniscectomy in these patients should be made on a clinical basis (mechanical symptoms, joint line tenderness, and so on), but even these features lack specificity in this group of patients.

CALCIFICATION OF THE MENISCI

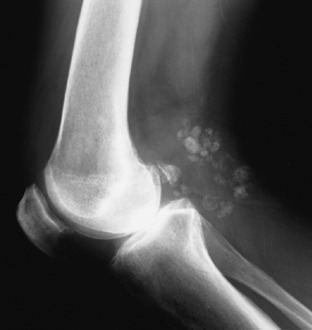

The meniscus can become calcified from a variety of causes (Fig. 11-10), the most common being degeneration and trauma. However, calcification can also occur in several other conditions, including degenerative arthritis, ochronosis, and pseudogout. The calcification itself is usually not painful. The symptoms are those that result from the primary disorder, and treatment is directed at that disorder.

Cysts

CLINICAL FEATURES

In children, the symptoms are usually related to the effects of direct pressure of the cyst on the adjacent soft tissues. Local discomfort may be present. In adults, the symptoms are related not only to the effects of the pressure of the cyst but also to the primary intraarticular abnormality. (Many cysts are asymptomatic, however.) The cyst commonly changes in size, depending on the activity of the patient and the amount of swelling in the knee.

Examination will reveal a cystic mass of variable size lateral to the medial hamstrings in the popliteal fossa (Fig. 11-11). The lesion may be locally tender. Other findings of primary joint disease may be present, especially in adults.

Except for occasional osteoarthritis, the roentgenogram is usually normal. Ultrasound studies are easy and can document the cystic nature of the lesion when the diagnosis is in doubt. They are also cost effective. MRI can identify underlying joint pathology as well. Occasionally, the cyst may even form multiple calcific loose bodies (Fig. 11-12).

TREATMENT

Adult patients are primarily treated nonsurgically. The cyst may be aspirated to reassure the patient of its benign nature. Aspiration, sometimes with injection of 1 mL of steroid, is often performed to relieve symptoms, and although recurrence is common, the symptoms are usually more tolerable. An intraarticular injection may also be needed to suppress the synovitis. If surgery is being considered, every attempt should be made to detect any underlying joint abnormality. Cyst excision without correction of the intraarticular abnormality is followed by a high rate of recurrence of the cyst. Correction of the intraarticular condition also frequently renders cyst excision unnecessary because the cyst becomes asymptomatic following elimination of the cause of the chronic effusion. Most patients are treated successfully by aspiration alone, or simple observation if the cyst is not symptomatic.

CYSTS OF THE MENISCUS

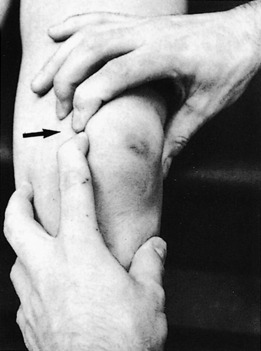

Cysts may also develop in a meniscus, usually the lateral, as a result of degeneration or trauma. The patient is generally a young adult who has a history of pain and a gradually enlarging mass over the lateral joint line (Fig. 11-13). A knee effusion may be present. Treatment consists of aspiration or meniscectomy and cyst excision if the patient is symptomatic.

Lesions of the Ligaments

CLINICAL FEATURES

TREATMENT

Treatment of cruciate injuries varies, depending on the age and activity of the patient and the presence of any additional injuries. Isolated ACL and PCL ruptures are generally treated nonsurgically, at least initially, in many cases. Reconstruction is usually required in patients with high demands. A well-constructed brace may provide an option in some patients. The treatment of combined cruciate/collateral injuries is unsettled. Surgery may be required to improve joint stability in the patient with multiple ligament involvement.

Minor ligament sprains are treated in the same manner as meniscus injuries (Fig. 11-19). Immobilization in a compression dressing with ice and elevation for 2 to 3 days are followed by exercises to promote absorption of swelling and restoration of motion and strength.

CHRONIC INSTABILITY

Patients often present with episodes of the knee “giving way” or “going out,” especially with activities that require cutting or changing directions. A chronic effusion may be present in the knee. Although a torn meniscus can cause similar symptoms, the most common cause of this problem is chronic instability caused by ACL deficiency. Although the initial disability from isolated ACL injuries may seem minimal, the injury may result in progressive deterioration with increasing knee laxity, tears in either meniscus, and articular cartilage degeneration. The ACL rupture has been referred to as “the beginning of the end” of the athlete’s knee.

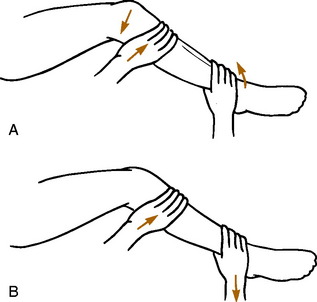

Older injuries often cause the knee to “give out,” a term usually called the pivot shift. This usually occurs when the patient comes to a sudden stop or changes directions quickly. The pivot shift is a sign that the tibia is subluxing on the femur. A synovitis is often present. The findings are often suggestive of meniscal injury (which may also be present), but the pivot shift test is usually diagnostic (Fig. 11-20).

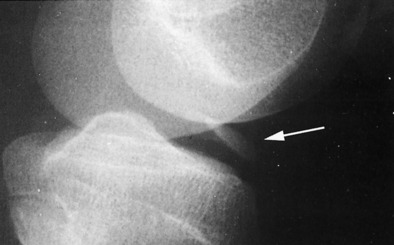

PELLEGRINI–STIEDA DISEASE

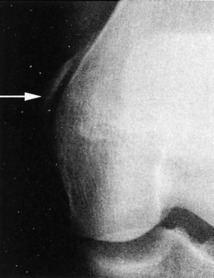

Occasionally, a sprain or repeated trauma of the medial collateral ligament is followed by the formation of a calcified mass at the site of the ligament injury, usually the femoral attachment (Fig. 11-21). This area of dystrophic calcification may remain tender and swollen for an extended period of time. Ossification of the mass may even occur. The symptoms gradually subside, and symptomatic treatment is usually all that is necessary. The mass rarely needs to be removed.

Disorders of the Extensor Mechanism

PATELLOFEMORAL PAIN SYNDROME

CLINICAL FEATURES

The majority of patients are teenagers or young adults. Crepitus is often the symptom of most concern. Pain beneath or near the patella is usually present, but many patients are unable to pinpoint the spot of maximal discomfort. Symptoms are characteristically aggravated by walking up and down stairs, an activity that puts the patella under the greatest flexion load. Squatting and prolonged sitting with the knee flexed (such as at the movie, the so-called “movie sign”) are also uncomfortable. This discomfort is often relieved by extension of the knee. Symptoms of giving way or locking may be present, and a history of previous trauma is common. The disease is frequently bilateral and may be confused with a meniscus injury or tendinitis.

Examination will reveal generalized tenderness around the patella, but the site is often not consistent or specific compared with the tenderness seen when quadriceps or patellar tendinitis is present. Direct pressure against the patella may be painful, and contraction of the quadriceps against patellar pressure is often uncomfortable (Fig. 11-22). Effusions are rare, unless the condition is associated with another problem such as a meniscal injury. Crepitus may be palpable during flexion and extension, although this finding is of debatable significance. There may also be signs of malalignment or an unstable patella, but commonly the examination is completely normal, except for tenderness around and beneath the patella. Roentgenographic examination is usually normal unless patellar subluxation is present.

TREATMENT

Most management programs emphasize conservative treatment. The patient is reassured of the benign nature of the problem. Treatment is directed toward the underlying cause, if any is present. “Flexion loads” should be avoided, especially improperly performed quadriceps exercises. Otherwise, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), ice after activities, moist heat, and an exercise program addressing flexibility and strength are advised (Table 11-1). Referral to physical therapy may be helpful, but any exercise program should be pain free. Most cases eventually recover spontaneously. Activities, including athletics, are allowed as tolerated. If symptoms persist, surgery may rarely be indicated. It usually consists of some procedure to realign the patella, if needed, to prevent abnormal motion or to release excessive lateral patellar pressure. Shaving or removal of “abnormal” articular cartilage is often only of limited value. Surgery has a high failure rate, probably because the cause of the disorder is not clearly understood. Arthroscopy may even trigger a sympathetic dystrophy in some cases. Anterior knee pain itself does not appear to lead to patellofemoral arthritis, but symptoms may persist for years.

| Stretch | Quads, hamstrings, triceps, heel cord |

| Strengthen | Quads (short arc) |

| Modalities | Ice, heat, massage? |

| Medication | NSAIDs |

NOTE: Eliminate overuse, flexion loads.

RECURRENT SUBLUXATION OF THE PATELLA

Recurrent subluxation of the patella (patellofemoral instability) is a common disorder that is often undiagnosed because the symptoms are similar to other derangements of the knee. In this condition, the patella subluxes or dislocates laterally. The onset is usually without any specific trauma, although it may follow an acute patellar dislocation that fails to heal properly. The disorder is frequently bilateral. The cause is often complex. Conditions that predispose the patella to not remain centralized in the femoral groove and track too far laterally are: (1) a shallow lateral femoral condyle; (2) a high Q angle (see Chapter 15); (3) inadequate development of the oblique portion of the vastus medialis muscle; (4) genu valgum; (5) ligamentous laxity; and (6) internal femoral torsion.

CLINICAL FEATURES

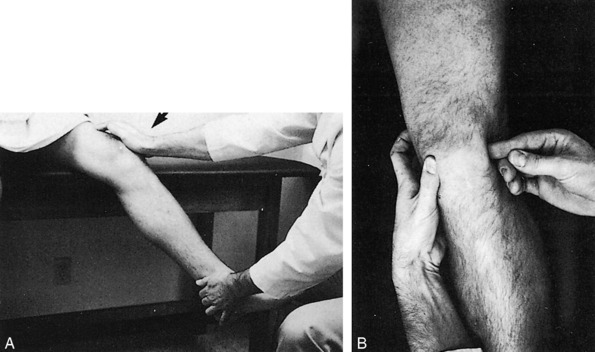

The symptoms are pain, swelling, and a sensation of the knee giving out. Acute dislocation may even occur, but more commonly, the symptoms are caused by recurrent subluxation. The patient may be able to describe the direction of movement of the patella. Physical examination usually reveals local tenderness over the medial facet of the patella and in the soft tissue medial to the patella. The patella may appear laterally displaced and higher than normal when the knee is slightly flexed (patella alta). Passive hypermobility with lateral displacement is often noted when pressure is applied against the patella with the knee relaxed in slight flexion (Fig. 11-23). This maneuver reproduces the sensation that the patient feels when the patella subluxes and often causes apprehension. Reflex contraction of the quadriceps muscle may also occur when the patella is manipulated. A joint effusion and mild quadriceps atrophy may be present. There are often findings of malalignment and mild laxity as well.

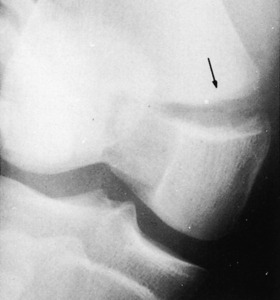

Roentgenographic studies are frequently helpful. A “sunrise” view taken with the knee relaxed in slight flexion will often reveal lateral displacement (Fig. 11-24).

TREATMENT

Treatment is directed at improving extensor muscle tone. Short arc quadriceps exercises are begun, and frequently, the vastus medialis portion of the quadriceps will strengthen enough to prevent recurrent lateral subluxation from occurring. The hamstrings are stretched if needed. Cycling may be helpful, and patellar stabilizing braces are sometimes prescribed.

ACUTE DISLOCATION OF THE PATELLA

A sudden valgus strain to the knee or a direct blow against the medial aspect of the patella may cause the patella to dislocate laterally (Fig. 11-25). The deformity is usually obvious, with the patella displaced in the lateral position and the knee held in slight flexion. There are usually no predisposing anatomic factors such as those seen with recurrent subluxation. Roentgenographic examination should always be performed to rule out any associated osteochondral fracture.

Occasionally, intravenous sedation may be needed. The knee is immobilized for 2 to 3 weeks by a knee immobilizer. Quadriceps exercises are begun as soon as possible. Traumatic dislocation is always accompanied by a partial rupture of the medial retinaculum and supporting structures of the patella. This may rarely lead to recurrent episodes of subluxation or dislocation. If it does, surgical reconstruction of the extensor mechanism may be necessary.

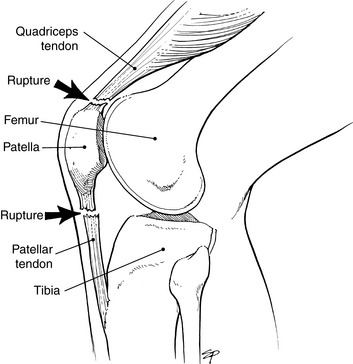

RUPTURES OF THE EXTENSOR MECHANISM

The extensor mechanism occasionally ruptures as a result of attrition. (Healthy, young tendon rarely ruptures.) Often, the rupture occurs during the course of normal activities, such as stair walking. The rupture may take place in the quadriceps or patellar tendon (Fig. 11-26). Patellar tendon ruptures are usually at its attachment to the patella. Active extension is immediately lost, but pain may be minimal, especially in an older patient with chronic degeneration of the muscle–tendon unit. Bilateral spontaneous quadriceps ruptures may be associated with diabetes, gout, and oral steroid use.

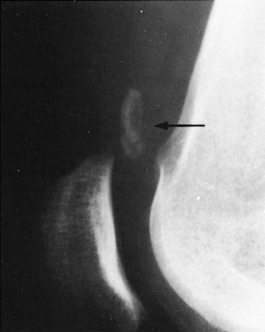

CLINICAL FEATURES

Clinically, hemorrhage and a palpable sulcus are present in the area of the rupture. Extension of the knee is markedly weakened or even completely absent. The patient is usually unable to perform a straight leg raise. A lateral roentgenogram taken with the knee in 90 degrees of flexion usually reveals proximal displacement of the patella (patella alta) when the rupture has occurred in the patellar tendon (Fig. 11-27). Roentgenograms are usually not helpful when the rupture has occurred proximal to the patella in the quadriceps mechanism.

OSGOOD–SCHLATTER DISEASE

Osgood–Schlatter disease is a disorder that involves the growing tibial tuberosity of adolescents. The cause is unknown, but the disorder is generally considered to be a traumatically produced lesion that occurs at the attachment of the patellar tendon to the tibial tuberosity. It is a self-limited condition that ends with closure of the upper tibial epiphyseal plate. The disorder usually becomes evident between the ages of 8 and 15 years and is frequently bilateral. Males are affected three times as often as females.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Although usually normal, a lateral roentgenogram of the upper portion of the tibia with the leg slightly internally rotated may reveal variable degrees of separation and fragmentation of the upper tibial epiphysis. Occasionally, the fragmented area fails to unite to the tibia and persists into adulthood (Fig. 11-28).

Osteochondritis Dissecans

CLINICAL FEATURES

The symptoms consist of pain, stiffness, and swelling that are worsened with activity. A painful limp is frequently present, and locking may even occur if the fragment has become detached. Diminished motion, swelling, and medial joint tenderness are usually present. This tenderness may be well localized and is best elicited by deep local pressure over the affected area with the knee flexed 90 degrees. Thigh atrophy may be seen, and Wilson’s sign may be abnormal (pain with knee extension and internal rotation of the foot).

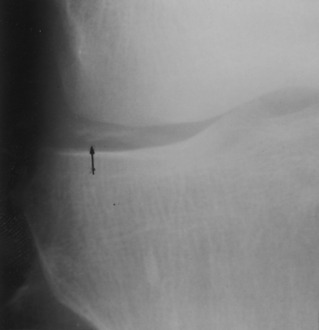

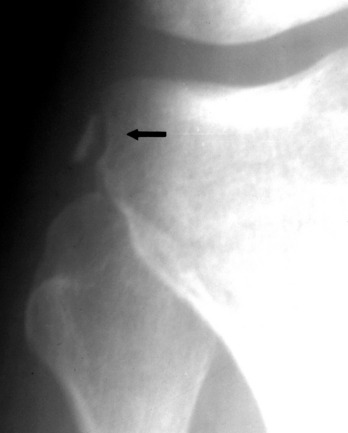

The roentgenogram is usually diagnostic (Fig. 11-29). A fragment of avascular bone is seen that is demarcated from the adjacent femur by a radiolucent line. Occasionally, a loose body may be present. Bone scanning and MRI may be helpful in management decisions.

Loose Bodies

CLINICAL FEATURES

Loose bodies may cause swelling and intermittent locking of the joint. There is frequently a feeling of weakness and instability. The loose body is occasionally palpable and freely movable. The roentgenogram is usually diagnostic (Fig. 11-30). A primary lesion such as osteochondritis dissecans may be detected, but frequently no joint abnormality other than the loose body is visualized.

Degenerative Arthritis

The knee is the joint most commonly affected by osteoarthritis. The main factor in its development is the aging process, and although the cause is unknown in most cases (primary osteoarthritis), obesity and malalignment of the lower extremity may play some role. Secondary or posttraumatic arthritis often develops after ligamentous injuries or severe trauma. The pathologic features were described in Chapter 10.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The symptoms are similar to those that occur with osteoarthritis in any other joint. The medial compartment is most commonly involved, which typically leads to increased bowing over time. Pain with activity that is relieved by rest is characteristic. Morning stiffness that is relieved by activity is also usually present. A chronic effusion is not uncommon. Crepitus and grating are also frequent complaints. Restriction of motion, joint swelling, local tenderness, and deformity are common clinical findings. Late stages are associated with pain at rest. The roentgenographic features consist of joint space narrowing, osteophyte formation, and sclerosis in the subchondral region (Fig. 11-31).

Osteonecrosis

ROENTGENOGRAPHIC FINDINGS

Initially, films are usually normal or show minimal degenerative arthritis consistent with the patient’s age. An early bone scan may show well-localized increased uptake over the involved area. MRI will also reveal the lesion. Eventually, radiolucency from a subchondral zone of sclerosis appears. The necrotic area frequently fragments and collapses, and this results in secondary osteoarthritis (Fig. 11-32).

Bursitis

Protective bursal sacs are present wherever soft tissue, such as muscle or tendon, moves over a bony prominence. They can become painful as a result of irritation or direct trauma. One such bursa that is frequently symptomatic in the knee is the anserine bursa. This bursa is located deep to the insertions of the semitendinosus, gracilis, and sartorius tendons medially (Fig. 11-33). Anserine bursitis is often difficult to separate from medial joint osteoarthritis. (Sometimes they occur together.) The tenderness from anserine bursitis is below the joint line.

Treatment measures include moist heat, rest, and the injection of a steroid/lidocaine mixture into the tender bursa (Fig. 11-34). NSAIDs are given to control pain and inflammation. Recurrent anserine bursitis is often related to osteoarthritis of the knee.

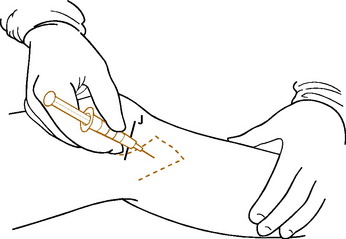

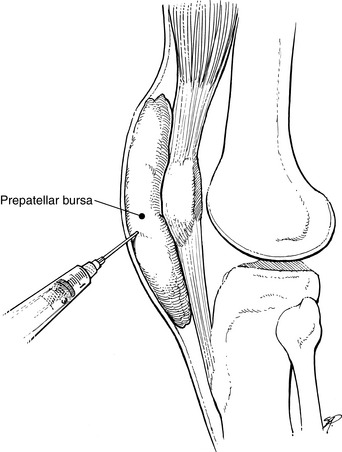

Acute traumatic prepatellar bursitis usually responds to rest. Aspiration may be performed for pain relief, but the fluid often returns. The fluid should be cultured if suspicious for infection. If infection develops, aspiration or open drainage followed by the appropriate antibiotic coverage is indicated. Incision and drainage should never be performed for sterile recurrent swelling because a chronic draining sinus tract may result. Recurrent bursal effusions may be aspirated repeatedly (Fig. 11-35). Eventually, most will “dry up” on their own. A chronic, swollen bursa that is vulnerable to repeated injuries may need to be excised.

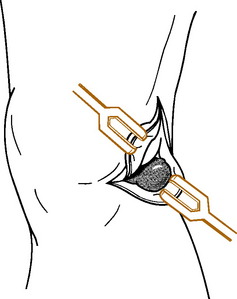

Arthroscopy

Arthroscopy is a valuable tool in the diagnosis and treatment of many disorders of the knee. It has also been used in the shoulder, elbow, hip, and ankle joint, but is most useful in problems of the knee. The procedure is safe and relatively minor with little morbidity. It is usually performed on an outpatient basis. Its diagnostic accuracy approaches 100%, and by using separate puncture holes of entrance, small instruments may be passed into the knee to perform a variety of functions. The most common are removal or repair of meniscus tears and removal of loose bodies. It is used to evaluate the knee of patients with Baker’s cyst to determine whether any intraarticular abnormality is present that may have caused the cyst to develop. In this case, the intraarticular problem might require treatment rather than the Baker’s cyst. Arthroscopic surgery is also frequently used to remove damaged articular cartilage from the patella in patients with chondromalacia, but the results in this condition are often inconsistent and unpredictable.

Fractures of the Knee

FRACTURES OF THE TIBIAL PLATEAU

A common fracture in the knee is an injury to the lateral tibial plateau (Fig. 11-36). This injury results from a force applied to the lateral aspect of the knee with the leg in the extended weight-bearing position. This is often caused by being struck by the bumper of a car. Undisplaced, impacted fractures are easily treated by a compression dressing and early motion with avoidance of weight bearing for 6 to 8 weeks. Displaced fractures require open reduction and internal fixation with elevation of the depressed plateau fragment.

FRACTURES OF THE PATELLA

Fractures of the patella are usually transverse and result from a fall onto the knee or a direct blow. They are classified as undisplaced or displaced (Fig. 11-37). Undisplaced (less than 8 mm) fractures are easily treated nonoperatively. A compression dressing followed by a removable splint may be all that is necessary in the conscientious patient. Otherwise, a cylinder cast or brace is applied and maintained for 5 to 6 weeks. This is followed by an active exercise program to restore strength and mobility.

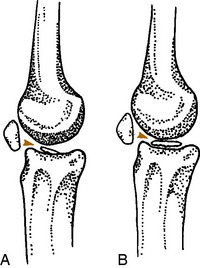

Patellar fractures are not to be confused with a bipartite patella (Fig. 11-38). This is a developmental variant that is often bilateral and usually asymptomatic. It is most often located in the superolateral pole of the patella and represents failure of this ossification center to unite with the main patella.

FRACTURES OF THE TIBIAL EMINENCE

Fractures of the intercondylar region of the tibia are more common in children than adults. They usually occur in the area of attachment of the ACL. If the fragment is only partially displaced, conservative treatment with immobilization for 8 weeks is usually sufficient (Fig. 11-39). Only the fracture that is completely avulsed and displaced from its bed requires surgical repair (Fig. 11-40) to restore strength to the cruciate ligament and prevent any mechanical blocking from occurring.

Traumatic Dislocation of the Knee

This is an uncommon injury but one that can be devastating. It usually results from severe trauma. Associated neurovascular injuries are very common, especially peroneal nerve damage. The dislocation is more commonly anterior (Fig. 11-41). Some injuries reduce spontaneously, which makes recognition of the exact nature of the injury difficult.

Aegerter E, Kirkpatrick JA. Orthopedic diseases, ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1968.

Bourne MH, Mazel WAJr, Scott SG, et al. Anterior knee pain. Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63:482-491.

Carpenter JE, Kasman R, Mathews LS. Fractures of the patella. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992:1550-1561.

Cutbill JW, Ladly KO, Bray RC, et al. Anterior knee pain: a review. Clin J Sports Med. 1997;7:40-45.

Duri ZA, Patel DV, Aichroth PM. The immature athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2002;21:461-482.

Ecker ML, Lotke PA. Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1994;2:173-178.

Ewing JW. Plica: pathologic or not? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993;1:117-121.

Fischer RL. Conservative treatment of patellofemoral pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 1986;17:269-272.

Garth WB. Current concepts regarding the anterior cruxiate ligament. Orthop Rev. 1992;21:565-575.

Geary M, Schepsis A. Management of first-time patellar dislocations. Orthopedics. 2004;27:1058-1062.

Good L, Johnson RJ. The dislocated knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:284-292.

Guhl JF. Update in the treatment of osteochondritis dissecans. Orthopedics. 1984;7:1744.

Helfet AJ. Disorders of the knee. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1974.

Insall J. Current Concepts Review: patellar pain. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:147-152.

Jackson RW. The painful knee: arthroscopy or MRI imaging? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1996;4:93-99.

Lotke PA, Ecker ML. Osteonecrosis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:470-473.

Matave MJ. Patellar tendon ruptures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1996;4:287-296.

Peh WC. Osteochondritis dissecans. Am J Orthop. 2004;33:46.

Sisto DJ, Warren RF. Complete knee dislocation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;198:94-101.

Stanitski CL. Anterior knee pain syndromes in the adolescent. Instr Course Lect. 1994;43:211-220.

Traina SM, Bronberg DF. ACL injury patterns in women. Orthopedics. 1997;20:545-552.