Chapter 45 The International Knee Documentations Committee Rating System

INTRODUCTION

In order to provide a comprehensive analysis of the knee condition and its impact on activity levels after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, some authors1,24 have suggested that rating systems measure a variety of symptoms, sports and daily activity functions, and objective findings. To our knowledge, only two such systems are available that measure all of these factors and that have established psychometric properties of reliability, validity, and responsiveness; the Cincinnati Knee Rating System (CKRS)3,16 and the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) system.9 Each of these systems measures pain, swelling, giving-way, functions of sports and daily activities, sports activity levels, patient perception of the knee condition, range of knee motion, joint effusion, tibiofemoral and patellofemoral compartment factors, knee ligament subluxations, radiographic indices, and function. The CKRS is described in detail in Chapter 44.

The IKDC is one of the most commonly used instruments to determine the results of ACL reconstruction and other knee operative procedures and has been considered a “gold standard” in the validity analyses and development of other systems.7,9,11,14 This chapter describes the history, development, initial forms, and revisions of the IKDC system. Investigations that provided reliability, validity, and responsiveness data are summarized. The major sections of the current knee forms are described.

HISTORY OF THE IKDC

As early as 1983, some authors5 expressed concern that comparing results of different methods of treatment of ACL ruptures was not possible without a standardized method of evaluation. At that time, a multitude of scoring systems had been proposed to quantify symptoms and functional limitations caused by ACL injuries and to evaluate the results of operative and conservative treatment. None of these systems was accepted internationally. One major problem was that the majority assigned numerical values to factors that were not quantifiable, weighted certain factors over others, and then added these scores together to provide an excellent, good, fair, or poor overall outcome grade. Because the content and relative weight given to each component varied greatly from one system to another, individuals rated as excellent or good on one instrument could be rated as fair or poor on another.24

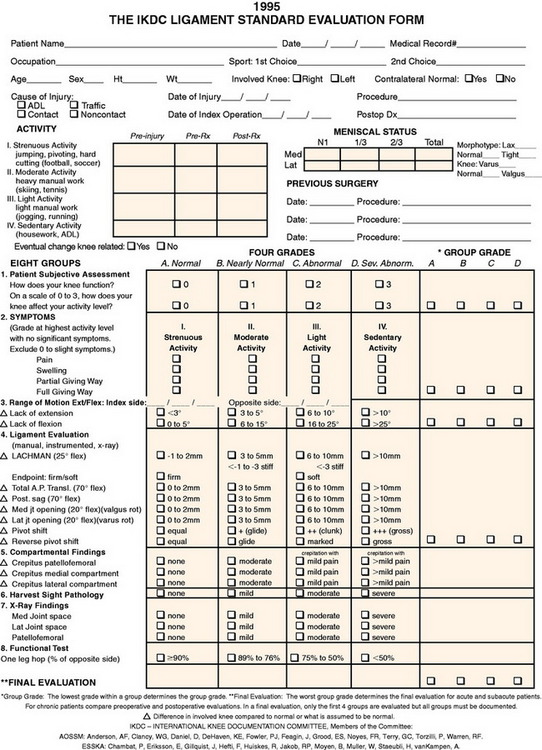

In order to develop a worldwide, standardized knee ligament rating system, a group of knee surgeons from Europe (European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy [ESKA]) and America (American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine [AOSSM]) founded the IKDC in 1987 (Table 45-1). Common terminology to describe knee motion and function were agreed upon by the committee members.19 A set of measurements to determine knee motion limits was validated in formal investigations.4,18,19 Methods to quantify knee function, activity levels, and symptoms were evaluated. A single-page Knee Ligament Standard Evaluation Form was then created (Fig. 45-1).6,11 The goals of the evaluation form were to measure the essential criteria judged at that time to be necessary to determine the results of treatment and to be simple enough to complete that research personnel were not required. The committee anticipated that a more comprehensive system would eventually be developed. The form evaluated sports activity levels and eight domains including patient assessment of knee function, symptoms, range of knee motion, ligament evaluation, compartment findings, harvest site pathology, radiographic findings, and single-leg hop function testing.

TABLE 45-1 Members of the International Knee Documentation Committee, 1987

| North American Members | European Members |

|---|---|

FIGURE 45-1 The 1995 International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) Knee Ligament Standard Evaluation Form.

(Reprinted with permission from the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, Rosemont, IL.)

The 1995 IKDC evaluation form adopted the philosophy of Noyes and coworkers (contained in the CKRS17,20) in the assessment of symptoms that were graded at the highest activity level possible without incurring pain, swelling, or giving-way. Two questions determined the patient assessment of knee function and its effect on activity level. A total of 24 factors were rated as either normal, nearly normal, abnormal, or severely abnormal, as shown in Figure 45-1. Four domains (patient subjective assessment, symptoms, range of motion, and ligament evaluation) received a final rating, and an overall evaluation result was derived, also using the same philosophy as that of the CKRS.3,16 In this manner, the lowest-graded factor determined the overall grade for each individual domain and the final evaluation. For example, a knee that had a positive pivot shift test and 6 mm of increased anteroposterior displacement on KT-2000 testing would receive an abnormal rating, even if all of the other categories were rated as normal or nearly normal. The form also rated sports activities according to a four-level gradient of strenuous, moderate, light, or sedentary.

Irrgang and associates11 evaluated the construct and concurrent validity of the 1995 IKDC evaluation form in 133 patients who were 1 to 5 years post–ACL reconstruction. These authors reported that the form was useful for reporting outcome after ACL reconstruction. The scoring system clearly distinguished patients whose outcomes were normal or nearly normal from those who were abnormal or severely abnormal, thus preventing a positively biased result when a significant problem in the knee persisted postoperatively. All the domains contributed to the final rating; however, symptoms and knee ligament evaluation accounted for 62% of the variance in the final rating. The authors did not conduct reliability or responsiveness testing in this investigation.

Paxton and colleagues21 reported the reliability and internal consistency of the 1995 IKDC evaluation form in 153 patients who had sustained patellar dislocations. The patients completed the form 2 to 5 years after their injury. Adequate reliability and internal consistency (correlation coefficients, 0.82 and 0.84, respectively) were reported. However, high ceiling effects were noted that indicated poor content validity for this group of patients.

COMPONENTS OF THE IKDC

The IKDC Knee scoring System currently includes six forms for research investigations. The IKDC is copyrighted by the AOSSM. All of the forms are available by contacting the AOSSM at http://www.aossm.org/tabs/Index.aspx

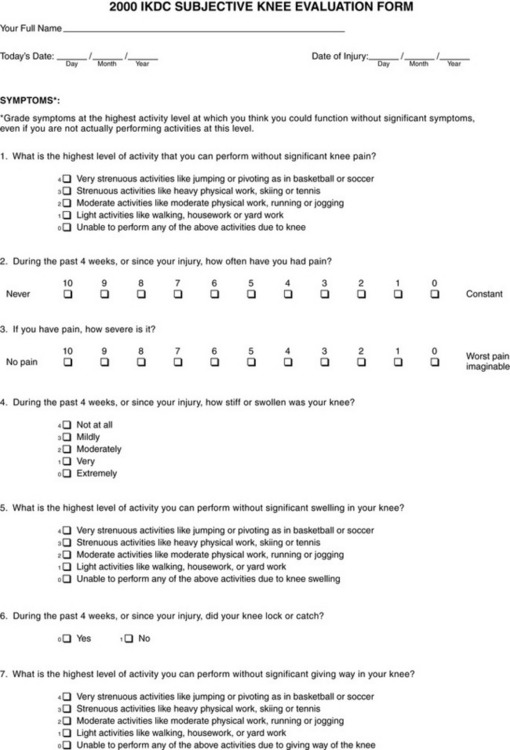

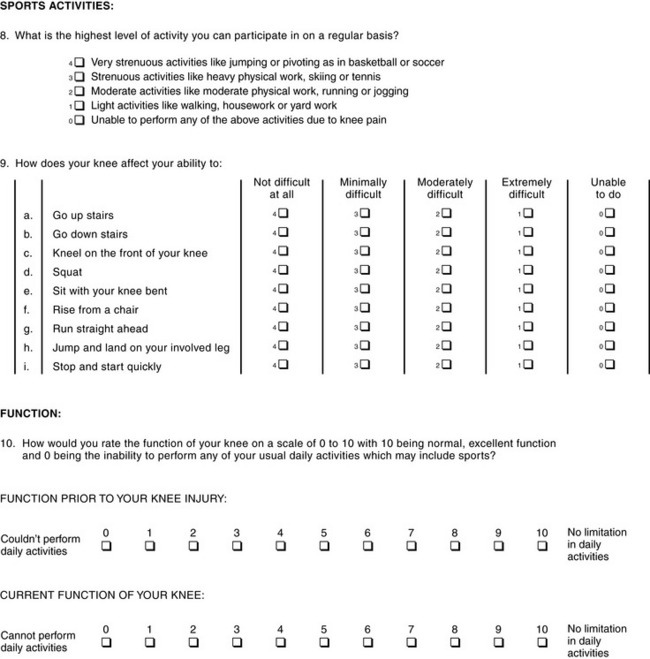

2000 IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form

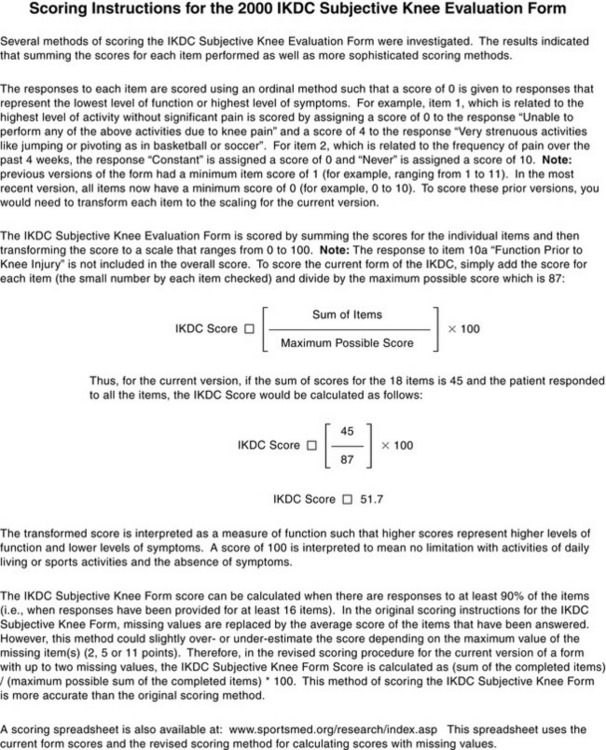

In 1997, the AOSSM elected to revise the IKDC rating system in order to broaden its application. The focus of the new committee (Table 45-2) shifted from designing and implementing a disease-specific (knee ligament) instrument to creating and testing a general (generic) knee problem instrument. Thus, the 2000 IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form (Fig. 45-2) was devised to rate symptoms and functional limitations for a variety of knee disorders and operations including ligament and meniscus tears, patellofemoral pain, and articular cartilage lesions. This form comprises 18 questions in the domains of symptoms, functions of daily and sports activities, current function of the knee, and participation in work and sports. An overall score is calculated on the sum of the questions answered (at least 90% of the questions must be answered) divided by the maximum possible score, as shown in Figure 45-2. The AOSSM provides an online scoring worksheet through its website that calculates a patient’s raw and percentile scores based on normative data. This form does not analyze findings from a physical examination, radiographs, knee arthrometer tests, function tests, or other objective tests.

TABLE 45-2 Members of the International Knee Documentation Committee, 1997

| North American Members | European Members |

|---|---|

| Ex-Officio Members | Pacific Rim Members |

|---|---|

FIGURE 45-2 The 2000 IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form.

(Reprinted with permission from the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, Rosemont, IL.)

Critical Points COMPONENTS OF THE INTERNATIONAL KNEE DOCUMENTATION COMMITTEE

2000 IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form

The 2000 IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form underwent reliability and validity testing in 533 patients9 and responsiveness testing in 207 patients who had a wide variety of knee problems.10 The overall score (scale, 0–100 points) had acceptable reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.94); convergent validity with the SF-36 scales of physical function, bodily pain, and the physical component summary score (Pearson correlation coefficients, 0.63, 0.64, and 0.66, respectively); and discriminate validity with the SF-36 subscales of mental health, role limitations due to mental problems, general health, and the mental components summary score. Adequate responsiveness, with a large effect size of 1.13 and a large standard response mean of 0.94, was reported. An additional evaluation of responsiveness was determined by ascertaining the change in the overall score (between treatment evaluations) that best distinguished patients who improved from those who did not. A change of 20.5 points had the greatest specificity in making this distinction, whereas a change of less than 12 points was not considered clinically relevant for indicating improvement.

Anderson and coworkers2 reported normative data obtained in a random sample of 5246 knees. The data collected allow comparison of a patient’s score to those of age- and gender-matched normal subjects. This investigation also demonstrated adequate construct validity of this form, because the overall score was able to identify patients who had knee symptoms and low levels of function. Slobogean and associates26 reported normative data obtained in a small random sample of 125 children aged 12 to 14 years. The mean score for this population (8 points) was identical to that of the young adulthood data published by Anderson and coworkers.2 However, the instrument’s psychometric properties have yet to be established in pediatric and adolescent patients.

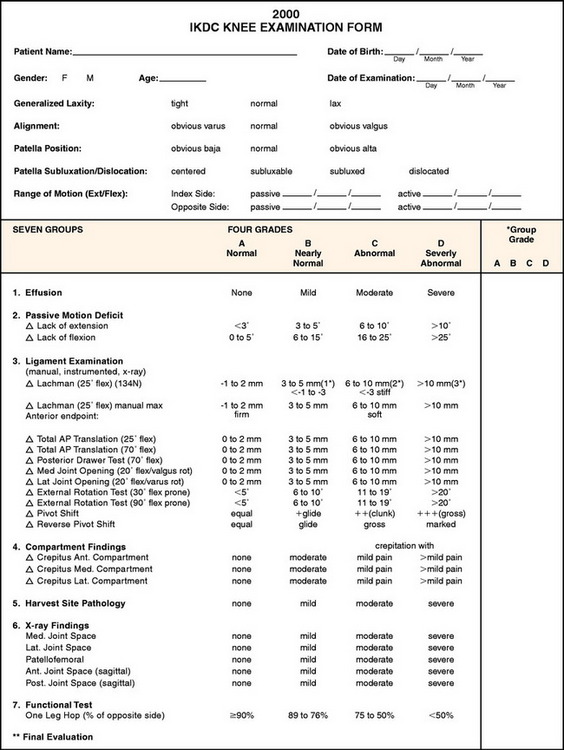

2000 IKDC Knee Examination Form

Because the 2000 IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form does not incorporate data from the physical examination, radiographs, knee arthrometer tests, function tests, or other objective tests, researchers are encouraged to also complete the 2000 IKDC Knee Examination Form (Fig. 45-3) to provide comprehensive data for publication. The 2000 IKDC Knee Examination Form is markedly similar to the original 1995 IKDC Knee Ligament Standard Evaluation form, except the original categories of patient subjective assessment and symptoms were eliminated and a rating of knee effusion was added to produce a total of seven domains. In addition, the original Sports Activity Scale was removed and inserted into the 2000 IKDC Subjective Knee Form.

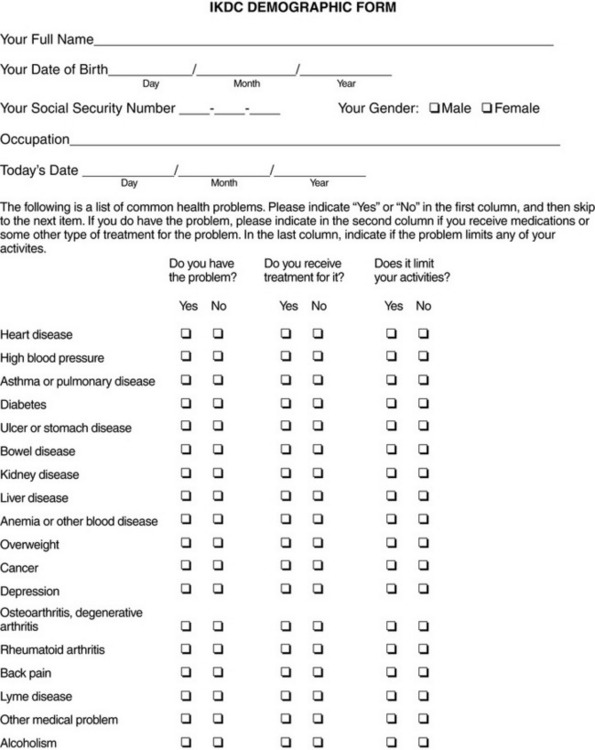

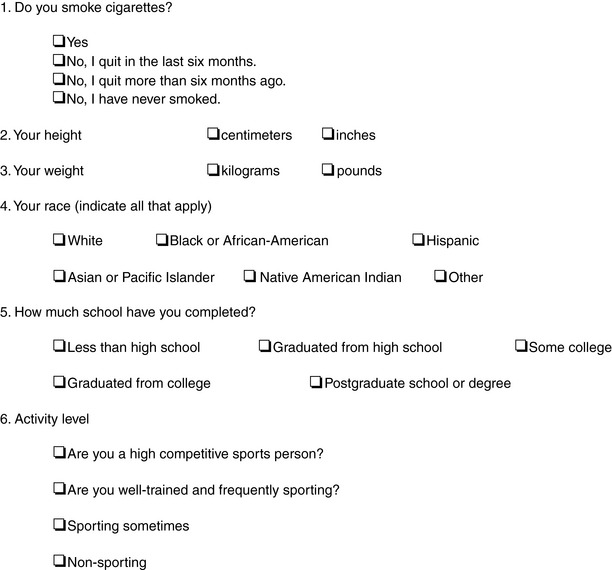

IKDC Demographic Form

The IKDC Demographic Form (Fig. 45-4) is a MODEMS-compatible questionnaire. The MODEMS project, developed by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons in 1995, was terminated in 2000. The system was expected to be the premier program for the collection and analysis of functional outcomes information on a variety of musculoskeletal conditions. The program was terminated owing to lack of subscribers and interest to maintain financial viability. Researchers who wish to remain MODEMS-compatible are required to complete the IKDC Demographic Form and Current Health Assessment Form.

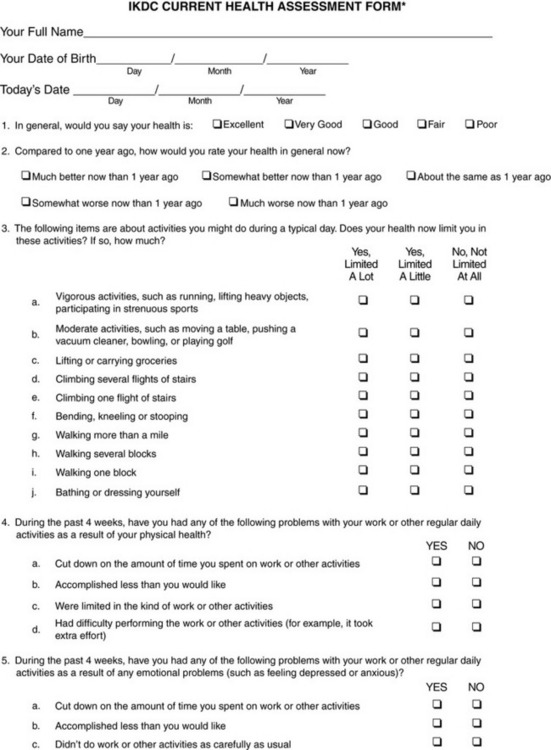

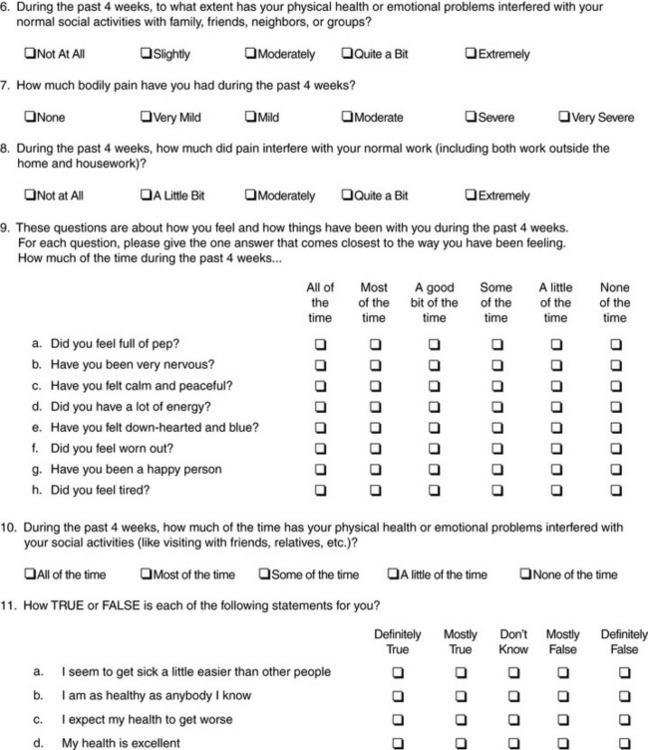

IKDC Current Health Assessment Form

The IKDC Current Health Assessment Form (Fig. 45-5) comprises 35 of the 36 questions from the SF-36. The reliability and validity of the SF-36 as a generic, patient-based health status instrument have been well documented.15,28,29 Shapiro and colleagues25 reported that the SF-36 was useful in showing significant changes with treatment for ACL ruptures treated either conservatively or surgically. These authors recommended including this outcome measure along with other disease-specific measures such as the IKDC Knee Examination Form when reporting outcome after ACL reconstruction.

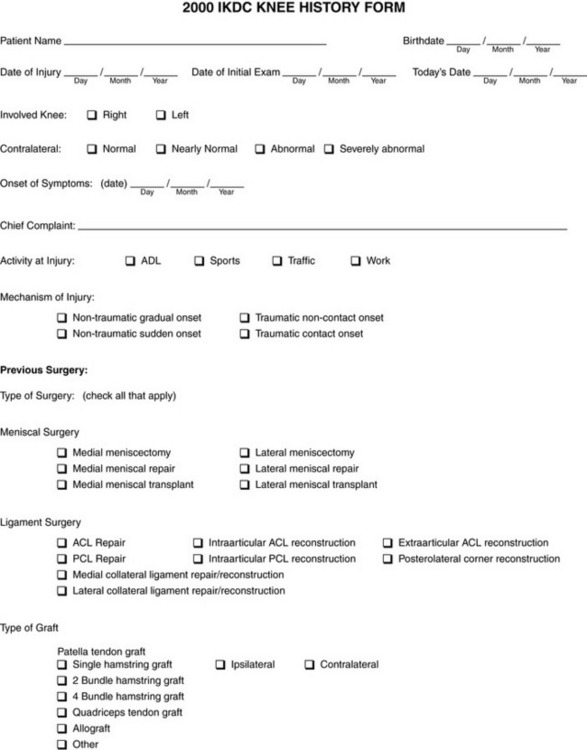

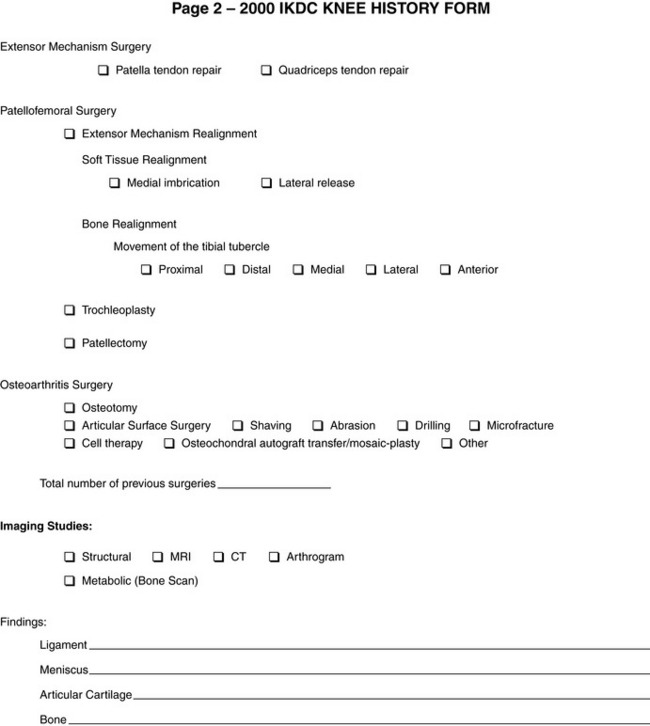

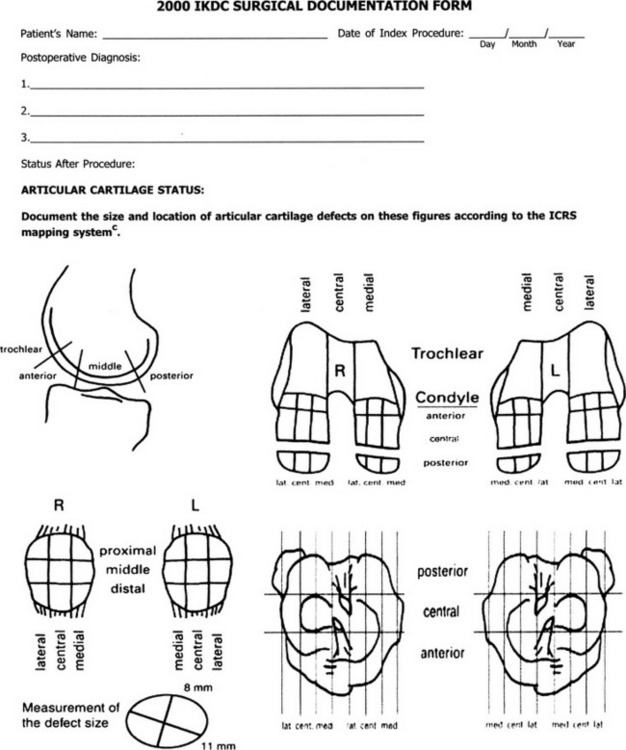

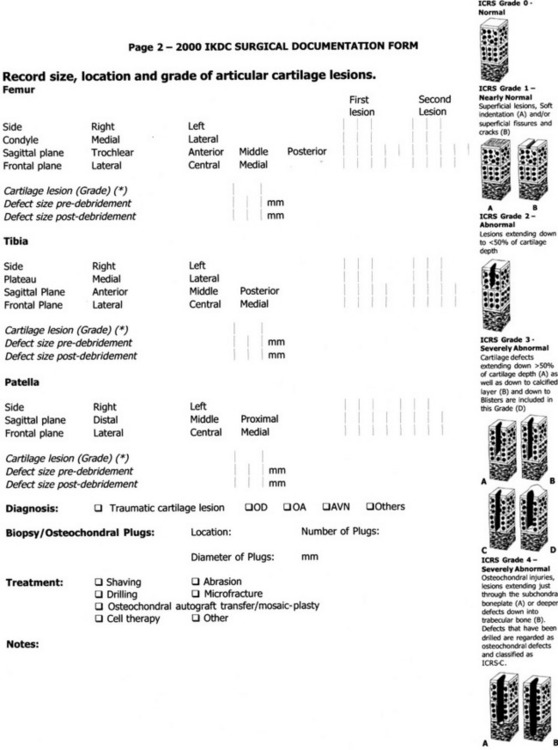

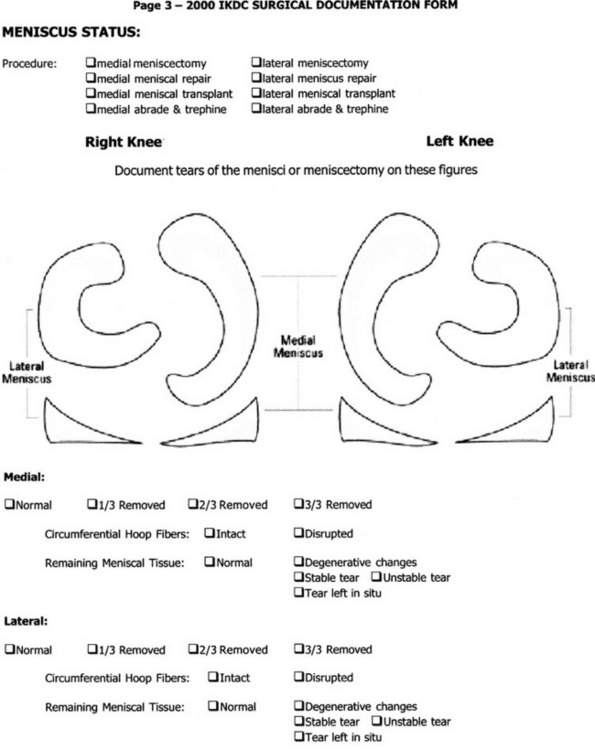

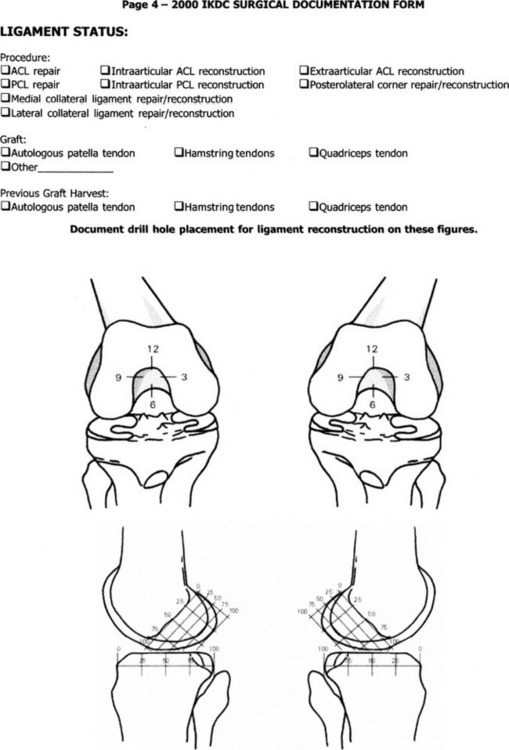

2000 IKDC Knee History and Surgical Documentation Forms

The 2000 IKDC Knee History Form (Fig. 45-6) allows documentation of injury history, previous knee surgery, and imaging studies. The 2000 IKDC Surgical Documentation Form (Fig. 45-7) includes the articular cartilage classification system of the International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS),6 described in further detail in Chapter 47, Articular Cartilage Rating Systems. The size, location, and grade (normal; ICRS grade 1, nearly normal; ICRS grade 2, abnormal; ICRS grade 3, severely abnormal; ICRS grade 4, severely abnormal) of articular cartilage lesions are recorded. This form also documents surgical procedures for articular cartilage lesions and meniscus and ligament damage. However, the form does not record other surgical procedures such as extensor mechanism realignment or osteotomy.

COMPARISON OF IKDC OUTCOMES WITH THOSE OF OTHER KNEE RATING SYSTEMS

To date, the majority of investigations that compared either the psychometric properties or the outcome scores of the IKDC with those of other systems used the 1995 IKDC evaluation form. Risberg and coworkers2 compared the responsiveness of the IKDC, Cincinnati, and Lysholm knee scores in 109 patients who were evaluated 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after ACL reconstruction. The IKDC domains analyzed were patient subjective assessment (IKDC-1), symptoms (IKDC-2), range of motion (IKDC-3), ligament examination (IKDC-4), and the final grade (IKDC-F).

Hrubesch and associates8 failed to find significant correlations between the IKDC rating and the Cincinnati, Lysholm, Feagin and Blake, Zarins and Rowe, and Marshall scores. However, these authors did not use the entire Cincinnati Knee Rating System, which incorporates variables similar to those of the IKDC knee examination form (see Chapter 44, The Cincinnati Knee Rating System). This was the reason that the superior results were found using the Cincinnati score compared with the IKDC overall grade.

Kocher and colleagues13 conducted a study to identify the determinants of patient satisfaction of the outcome of ACL reconstruction. Patient satisfaction was significantly associated with the IKDC-1 to IKDC-3 (subjective assessment, symptoms, range of motion) and IKDC-F. There was no association between IKDC-4 (ligament examination) and patient satisfaction.

AUTHORS’ COMMENTS

It is important to realize the limitations of the 2000 IKDC Subjective Knee Form. First, this form is, by intended design, a generic knee questionnaire. The authors believe that investigators should use instruments as sensitive to the condition under study as possible and understand, therefore, that generic questionnaires have limited usefulness in investigations composed of patients with a specific diagnosis. Second, this form combines data from 18 questions that rate symptoms, functions of daily and sports activities, current function of the knee, and participation in work and sports into one numerical value. The IKDC to date has not recommended that researchers separately assess specific symptoms, functional limitations, or sports activity levels before and after treatment, even though the questionnaire format allows for such an assessment. Therefore, given the current committee recommendations, the ability to detect specific limitations, such as pain or giving-way during various activities, is not possible. Investigators and readers cannot ascertain from a single numerical value whether an individual is participating in athletics and, if so, whether problems are incurred. Changes in sports activity levels are not determined, nor are limitations in individual knee functions such as walking, running, and pivoting. The authors believe that it is important in athletically active populations to provide a specific analysis of the sports levels pre- and postoperatively, which may be easily done by reporting the distribution of patients in the five levels provided in question #8. It is equally important to report the percentage of patients who returned to athletics without symptoms versus those who experienced problems and were considered knee abusers.20

In the authors’ opinion, the age- and gender-matched percentiles generated by the AOSSM online scoring system for the 2000 IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form are more useful than the total score. For instance, a 46-year-old woman who experiences only mild, occasional symptoms with strenuous activities could score an 87.36, which initially appears to be a good result and would compare favorably with scores of other systems such as the Lysholm27 or Activities of Daily Living Scale of the Knee Outcome Survey.12 However, this total score places this patient into only the 50th percentile according to the IKDC normative database. Therefore, researchers should consider incorporating the age- and gender-matched percentiles in the results section of published studies, such as is commonly done with SF-36 data. An example of this type of analysis with SF-36 data may be found in the investigation of Sekiya and coworkers23 who described the short-term (average, 2.8 yr postoperative) outcome of combined meniscus transplantation and ACL reconstruction in 28 patients. The mean absolute scores were provided for the individual domains of the SF-36 questionnaire, along with scores standardized to age- and sex-matched U.S. population norms for each individual patient.

1 Anderson A.F., Federspiel C.F., Snyder R.B. Evaluation of knee ligament rating systems. Am J Knee Surg. 1993;6:67-73.

2 Anderson A.F., Irrgang J.J., Kocher M.S., et al. The International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Evaluation Form: normative data. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:128-135.

3 Barber-Westin S.D., Noyes F.R., McCloskey J.W. Rigorous statistical reliability, validity, and responsiveness testing of the Cincinnati Knee Rating System in 350 subjects with uninjured, injured, or anterior cruciate ligament–reconstructed knees. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:402-416.

4 Daniel D.M. Assessing the limits of knee motion. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:139-147.

5 Feagin J., Blake W.P. Postoperative evaluation and result recording in the anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;172:143-147.

6 Hefti F., Muller W., Jakob R.P., Staubli H.U. Evaluation of knee ligament injuries with the IKDC form. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1993;1:226-234.

7 Hoher J., Munster A., Klein J., et al. Validation and application of a subjective knee questionnaire. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1995;3:26-33.

8 Hrubesch R., Rangger C., Reichkendler M., et al. Comparison of score evaluations and instrumented measurement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:850-856.

9 Irrgang J.J., Anderson A.F., Boland A.L., et al. Development and validation of the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:600-613.

10 Irrgang J.J., Anderson A.F., Boland A.L., et al. Responsiveness of the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1567-1573.

11 Irrgang J.J., Ho H., Harner C.D., Fu F.H. Use of the International Knee Documentation Committee guidelines to assess outcome following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1998;6:107-114.

12 Irrgang J.J., Snyder-Mackler L., Wainner R.S., et al. Development of a patient-reported measure of function of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1132-1145.

13 Kocher M.S., Steadman J.R., Briggs K., et al. Determinants of patient satisfaction with outcome after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:1560-1572.

14 Marx R.G., Stump T.J., Jones E.C., et al. Development and evaluation of an activity rating scale for disorders of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:213-218.

15 McHorney C.A., Ware J.E., Rachel J.F., Sherbourne C.D. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40-66.

16 Noyes F.R., Barber S.D., Mangine R.E. Bone–patellar ligament–bone and fascia lata allografts for reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:1125-1136.

17 Noyes F.R., Barber S.D., Mooar L.A. A rationale for assessing sports activity levels and limitations in knee disorders. Clin Orthop. 1989;246:238-249.

18 Noyes F.R., Cummings J.F., Grood E.S., et al. The diagnosis of knee motion limits, subluxations, and ligament injury. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:163-171.

19 Noyes F.R., Grood E.S., Cummings J.F., Wroble R.R. An analysis of the pivot shift phenomenon. The knee motions and subluxations induced by different examiners. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:148-155.

20 Noyes F.R., Mooar P.A., Matthews D.S., Butler D.L. The symptomatic anterior cruciate–deficient knee. Part I: the long-term functional disability in athletically active individuals. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:154-162.

21 Paxton E.W., Fithian D.C., Stone M.L., Silva P. The reliability and validity of knee-specific and general health instruments in assessing acute patellar dislocation outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:487-492.

22 Risberg M.A., Holm I., Steen H., Beynnon B.D. Sensitivity to changes over time for the IKDC form, the Lysholm score, and the Cincinnati Knee Score. A prospective study of 120 ACL reconstructed patients with a 2-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1999;7:152-159.

23 Sekiya J.K., Giffin J.R., Irrgang J.J., et al. Clinical outcomes after combined meniscal allograft transplantation and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:896-906.

24 Sgaglione N.A., Del Pizzo W., Fox J.M., Friedman M.J. Critical analysis of knee ligament rating systems. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:660-667.

25 Shapiro E.T., Richmond J.C., Rockett S.E., et al. The use of a generic, patient-based health assessment (SF-36) for evaluation of patients with anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:196-200.

26 Slobogean G.P., Mulpuri K., Reilly C.W. The International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Evaluation Form in a preadolescent population: pilot normative data. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:129-132.

27 Tegner Y., Lysholm J. Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;198:43-49.

28 Ware J.E., editor. SF-36 Health Survey. Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1997.

29 Ware J.E., Sherbourne C.D. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.