Chapter 2 The Intensivist in the New Hospital Environment

Patient Care and Stewardship of Hospital Resources

Many studies in the literature have reported that management of the ICU and critically ill patients by intensivists increases survival rates and decreases resource utilization.1–4 In addition to improvement in resource utilization, Gajic et al.3 reported that the presence of a critical care specialist was associated with improved staff satisfaction, an important consideration when considering the increasing staffing limitations. Not all studies have reported a benefit in outcome, however. In sharp contrast to the many studies showing improved outcomes associated with intensivist staffing, Levy et al.5 reported that patients managed by intensivists had a higher risk of death than did those who were not managed by them. It is not clear why this study had such disparate results from previous studies, but one likely reason is that the study design was very different from that of previous studies, as were the definitions used.6 The systematic review by Pronovost et al.1 defined high-intensity staffing as the ICU policy requiring that the intensivist have responsibility for care for all of the patients in the ICU (closed ICUs) or that there be a mandatory consultation by an intensivist. In the study by Levy et al.,5 the involvement of the intensivist was elective (i.e., not decided at the unit level but by the choice of the attending physician). According to the definition by Pronovost et al.,1 ICUs that allow the choice of whether to involve an intensivist are low-intensity staffing models. The effect of intensivists in low-intensity–staffed ICUs has not been studied adequately. Levy et al.5 did a separate analysis of no-choice ICUs versus choice ICUs and reported that the mortality rate was higher in the no-choice ICUs, raising the question again as to whether intensivist staffing may increase mortality rates, although a mechanism by which this outcome might occur is not apparent. The preponderance of available studies continues to show a benefit of management by an intensivist.

Unlike adult critical care units, nearly all pediatric ICUs have trained pediatric intensivists who manage most (if not all) of the patients. In the United States, only about 30% of the adult ICUs are staffed by trained intensivists. Regionalization of trauma services for adults has improved outcomes of trauma patients.7 Regionalization has been recommended as a way to improve the care of critically ill or injured adults and children, although the barriers to regionalization are far greater for adults than for children.8,9 Regionalization effectively puts limited resources together to maximize the effectiveness and availability of these resources to a greater number of patients, although at the expense of travel for many patients and their families.

Organization and Quality Issues

During the past 2 decades, the cost of health care in the United States has increased dramatically, with hospital costs increasing more rapidly than other cost indexes. Controlling critical care medicine costs will be an important issue as health care reform is discussed. Critical care consumes an increasing proportion of hospital beds as the acuity of hospital inpatients increases. Although the cost of critical care is rising, the proportion of national health expenses used in critical care medicine has decreased over time.10,11 Different methods for calculating critical care medicine costs create some discrepancies in the estimates of these costs, making it difficult to ensure that efforts to control costs are really effective. The ICU provides support to a variety of services that could not be offered without ICU care, such as cardiac surgery and transplantation. Defining the ICU as the cost center gives a very different picture of the expense of ICU care than would attributing the costs of such patients to the services that use the ICU. Similarly, attributing some of the revenue that such services generate to the ICU and critical care physicians rather than solely to the surgical service per se provides a different view of the value of the ICU to the institution. Different strategies for controlling costs have potential benefit but often have unintended consequences. Shifting costs from the ICU to the supporting hospital services further complicates efforts to account for accurate ICU costs. True critical care medicine cost containment is extremely difficult, if not impossible.12

Effective multidisciplinary care requires developing a teamwork model in the ICU. True teamwork recognizes the importance of the role of each member of the team and requires respect and trust for the other professions represented on the team. Effective communication between all members of the health care team and the patient/family cannot be overemphasized. A collaborative partnership with shared responsibility for maintaining communication and accountability for patient care includes the recognition that no one provider can perform all parts of patient care; the whole team is much more effective than each member of the team alone. True teamwork is a complementary relationship of interdependence.13

An effective team is critical to both the clinical and financial health of the ICU.14 Good teamwork requires a number of skills. A team performance framework for the ICU requires communication, leadership, coordination, and team decision making. Effective team leadership is crucial for guiding effective team interactions and coordination. Leadership performance can be measured; the leadership performance of attending intensivists is associated with accomplishment of daily patient goals.15 Important leadership characteristics include communication skills, conflict management, time management, acknowledging others’ concerns and one’s own limitations, focus on results, setting high standards, and showing appreciation for the work of the team.

Quality improvement is an important part of ICU management. The intensivist must be responsible for leading and ensuring quality improvement efforts. The Institute of Medicine’s “six aims for improvement” are safety, effectiveness, equity, timeliness, patient centeredness, and efficiency.16 These aims are certainly relevant to pediatric critical care practice and can provide a framework for improving quality in the pediatric ICU (PICU). Acuity scores have been used as tools for measuring quality in the ICU. It is important for the intensivist to understand the various available scoring systems and how they can be used to ensure appropriate use of these tools.17

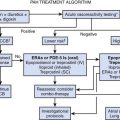

The use of clinical pathways has been shown to improve efficiency of care and decrease resource utilization.18 The intensivist, as leader of the team, must ensure that these guidelines are developed with input from all members of the ICU team to optimize acceptance and smooth implementation of such guidelines. Standardization of care increases the likelihood that every patient will get the appropriate treatments at the right time. A common objection to standardization is that ICU patients are too complex or too different to be able to standardize their care. However, some aspects of care should be provided to most, if not all, patients and can be overlooked easily if they are not standardized. One example is insertion of central venous catheters using full-barrier precautions to prevent line-associated bloodstream infections. Checklists are helpful to remind all members of the team to carry out the “routine” steps every time. In the case of a patient who has a contraindication to “standard” care, the contraindication should be documented. In an environment that is increasingly complex, ensuring reliability in processes of care is exceedingly difficult. Standardizing the processes means that everyone on the team knows what to expect. Empowering every member of the team to speak up if he or she observes an unsafe condition further increases the safety of the patient and the reliability of care.

A systematic review by Carmel and Rowan19 described eight organizational categories that may contribute to patient outcome in the ICU. These factors include staffing, teamwork, patient volume and pressure of work, protocols, admission to intensive care, technology, structure, and error. Pollack and Koch20 demonstrated that organizational factors and management characteristics can influence health outcomes in the neonatal ICU. The intensivist, as captain of the ship, is responsible for ensuring that these important organizational factors are optimized in the ICU.

Manpower Issues

By its very nature, critical care is an intense and stressful field. Optimal clinical care and management in the ICU depends first and foremost on the availability of sufficient numbers of trained critical care professionals. Shortages of all types of critical care providers are an increasing concern. The Society of Critical Care Medicine, the American College of Chest Physicians, and the American Thoracic Society performed a manpower analysis of critical care specialists in 1997 and projected an increasing shortage of intensivists during the next 2 decades.21 These three professional societies, along with the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, further reviewed the available literature to identify causes of the shortage of critical care professionals and possible approaches to redesigning critical care practice.22 These groups recommended common standards across the critical care field to promote uniformity and quality, use of information technology to promote standardization and improve efficiency, government incentives to attract health care professionals to critical care, and sponsorship of research defining the optimum role for intensive care professionals in the delivery of critical care. In an interesting study that looked at intensivist/bed ratio, Dara and Afessa23 reported that differences in intensivist/bed ratios from 1:7.5 to 1:15 were not associated with differences in mortality rates, but a ratio of 1:15 was associated with increased ICU length of stay. Shortages of intensivists, which lead to higher numbers of patients per intensivist, may further limit the availability of ICU beds by increasing the length of stay. Although these projects and the resulting documents were primarily aimed at critical care services for adults, the need for which will unquestionably increase markedly as the population ages, there are similar and equally pressing shortages of well-trained pediatric critical care professionals.24 The pediatric intensivist needs to be aware of the importance of the health care professional as one of the most important resources of the PICU.

A matter that is at least as concerning as the physician shortage in the ICU is the increasing shortage of critical care nurses. As the supply of nurses decreases, the nurse/patient ratio in many ICUs increases. Increasing the number of critically ill patients a nurse must care for has negative effects on both patient care and on nursing morale and job satisfaction.25,26 Decreased morale leads to increased turnover and the loss of experienced and highly skilled nurses. This situation, in turn, places patients at increased risk.

The presence of a pharmacist on rounds in the ICU has been shown to reduce drug errors and improve patient safety. Pharmacists are another group of critical care professionals who are in increasingly short supply.27

With the increasing shortage of intensivists has come consideration of other ways to provide adequate numbers of practitioners to care for critically ill patients. Hospitalists provide a substantial amount of critical care in the United States. One study reported that after-hours care in the PICU by hospitalists was associated with improved survival rates and shorter length of stay compared with care by residents.28 Numerous studies have looked at the role of nurse practitioners and physician assistants as physician extenders in the PICU.29–31 These practitioners can effectively complement the physician staff in the ICU, especially as resident work hours decrease.

1. Pronovost P.J., Angus D.C., Dorman T., et al. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;288:2151-2162.

2. Fuchs R.J., Berenholtz S.M., Dorman T. Do intensivists in ICU improve outcome? Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2005;19:125-135.

3. Gajic O., Afessa B., Hanson A.C., et al. Effect of 24-hour mandatory versus on-demand critical care specialist presence on quality of care and family and provider satisfaction in the intensive care unit of a teaching hospital. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:36-44.

4. Brilli R.J., Spevetz A., Branson R.D., et al. Critical care delivery in the intensive care unit: defining clinical roles and the best practice model. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2007-2019.

5. Levy M.M., Rapoport J., Lemeshow S., et al. Association between critical care physician management and patient mortality in the intensive care unit. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:801-809.

6. Rubenfeld G.D., Angus D.C. Are intensivists safe? Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:877-879. editorial

7. MacKenzie E.J., Rivara F.P., Jurkovich G.H., et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:366-378.

8. Kahn J.M., Branas C.C., Schwab C.W., et al. Regionalization of medical critical care: what can we learn from the trauma experience? Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3085-3088.

9. Accm, Sccm, Pediatric Task Force on Regionalization of Pediatric Critical Care, AAP Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine: Consensus report for regionalization of services for critically ill or injured children. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:236-239.

10. Halpern N.A., Pastores S.M., Greenstein R.J. Critical care medicine in the United States 1985-2000: an analysis of bed numbers, use, and costs. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1254-1259.

11. Milbrandt E.B., Kersten A., Rahim M.T., et al. Growth of intensive care unit resource use and its estimated cost in Medicare. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2504-2510.

12. Halpern NA: Can the costs of critical care be controlled? Curr Opin Crit Care 15:591–596, 2009.

13. Sherwood G., Thomas E., Bennett D.S., et al. A teamwork model to promote patient safety in critical care. Crit Care Nurs Clin N Am. 2002;14:333-340.

14. Reader T.W., Glin R., Mearns K., et al. Developing a team performance framework for the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1787-1793.

15. Stockwell D.C., Slonim A.D., Pollack M.M. Physician team management affects goal achievement in the intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8:540-545.

16. Slonim A.D., Pollack M.M. Integrating the Institute of Medicine’s six quality aims into pediatric critical care: relevance and applications. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:264-269.

17. Marcin J.P., Pollack M.M. Review of the acuity scoring systems for the pediatric intensive care unit and their use in quality improvement. J Intens Care Med. 2007;22:131-140.

18. Holcomb B.W., Wheeler A.P., Ely E.W. New ways to reduce unnecessary variation and improve outcomes in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7:304-311.

19. Carmel S., Rowan K. Variation in intensive care unit outcomes: a search for the evidence on organizational factors. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7:284-296.

20. Pollack M.M., Koch M.A. Association of outcomes with organizational characteristics of neonatal intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1620-1629.

21. Angus D.C., Kelley M.A., Schmitz R.J., et al. Current and projected workforce requirements for care of the critically ill and patients with pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2000;284:2762-2770.

22. Kelley M.A., Angus D.C., Chalfin D.B., et al. The critical care crisis in the United States: a report from the profession. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1219-1222.

23. Dara S.I., Afessa B. Intensivist-to-bed ratio: association with outcomes in the medical ICU. Chest. 2005;128:567-572.

24. Stromberg D. Pediatric cardiac intensivists: are enough being trained? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5:391-392.

25. Marcin J.P., Rutan E., Rapetti P.M., et al. Nurse staffing and unplanned extubation in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:254-257.

26. Aiken L.H., Clarke S.P., Sloane D.M., et al. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288:1987-1993.

27. Leape L.L., Cullen D.J., Clapp M.D., et al. Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 1999;282:267-270.

28. Tenner P.A., Dibrell H., Taylor R.P. Improved survival with hospitalists in a pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:847-852.

29. DeNicola L., Kleid D., Brink L., et al. Use of pediatric physician extenders in pediatric and neonatal intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:1856-1864.

30. Mathur M., Rampersad A., Howard K., et al. Physician assistants as physician extenders in the pediatric intensive care unit setting: a 5-year experience. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:14-19.

31. Kleinpell R.M., Ely E.W., Grabenkort R. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the intensive care unit: an evidence-based review. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2888-2897.