The integumentary system

The integumentary system consists of the skin and its appendages: eccrine, apocrine, apoeccrine, and sebaceous glands; hair; and nails. Functions of the skin include protection from physical and chemical injury, infection, and ultraviolet radiation; modulation of transepidermal water fluxes; prevention of fluid loss and fluid and electrolyte imbalances; and thermoregulation. The skin is also important in sensation (pain, pressure, touch, and temperature), tactile discrimination, contributes to maintenance of blood pressure by dilation or constriction of the peripheral capillaries, and contains precursor molecules for vitamin D.49

Maternal physiologic adaptations

Antepartum period

The basis for changes in the skin, hair, and secretory glands during pregnancy are thought to be hormonal—especially the effects of estrogens and adrenocortical steroids. Similar alterations are often seen in women using oral contraceptives. There is a familial tendency or genetic predisposition for some of the cutaneous and vascular changes.77,118

Alterations in pigmentation

Alterations in pigmentation are common during pregnancy and include hyperpigmentation of specific areas of the body and melasma (chloasma). In early pregnancy, hyperpigmentation is thought to be due to the effects of estrogens and progesterone on melanocytes. This finding is also consistent with reports of alterations in pigmentation associated with use of oral contraceptives.31 Progression is also thought to be related to the effects of placental corticosteroid-releasing hormone and of pro-opiomelanocortin peptides such as adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH), β-endorphin (see Chapter 19), and possibly placental lipid stimulation of tyrosinase (enzyme involved in production of melanin).77,85,90,93,96

Hyperpigmentation.

Hyperpigmentation is the most frequent integumentary alteration during pregnancy. Changes in pigmentation are seen in up to 91% of pregnant women, tend to be more frequent in women with dark hair or complexions, and are progressive throughout pregnancy.62 Most women experience a mild, generalized increase in pigmentation that is especially prominent in areas of the body that tend to be naturally more intensely pigmented. These areas include the areolae, genital skin, axillae, inner aspects of the thighs, and linea alba.23,28,61,77,93

The linea alba is a tendinous median line that extends along the anterior of the abdomen from the umbilicus to the symphysis pubis and occasionally superiorly to the xiphoid process. Hyperpigmentation during pregnancy causes the linea alba to darken and become the linea nigra. Up to one third of women on oral contraceptives also develop a linea nigra. Pigmentary changes tend to fade during the postpartum period in fair-skinned women, but some pigmentary changes may remain in women with darker skin and hair. Hyperpigmentation may be exacerbated by sun exposure.28,61,93,96

Freckles, nevi, and recent scars may darken during pregnancy, perhaps due to an up-regulation of receptors for estrogens and progesterone on the nevus cell surface.27 Existing melanocytic nevi may increase in size or new nevi may develop during pregnancy, although some have reported that existing melanocytic nevi do not change significantly during pregnancy.57 Increased malignant degeneration of nevi is not seen during pregnancy.57,85 Prophylactic removal of nevi following pregnancy may be considered. Any nevi showing signs suggestive of malignancy should be excised.28,61,93,96

Although rare, some women may develop pigmentary demarcation lines, which are areas of hypopigmentation that follow the distribution of peripheral cutaneous nerves, and disappear after delivery. The lines are thought to be due to prolonged uterine compression of these nerves, particularly at S1-S2, leading to a sharp demarcation between pigmented and hypopigmented areas.2,89,93

Melasma.

Melasma (also known as chloasma or the “mask of pregnancy”) is a common occurrence in pregnant women.5,15,77,93,96 Melasma is characterized by irregular, blotchy areas of pigmentation on the face, usually bilateral and symmetrical and seen most commonly on the cheeks, chin, and nose.77 The areas of altered pigmentation are not elevated and can range in color from light to dark brown. Three distribution patterns have been described: centrofacial (63%), involving the cheeks, forehead, upper lip, nose, and chin; malar (21%), over the cheeks and nose; and mandibular (16%), over the ramus of the mandible.5 Three histological patterns have also been identified: epidermal (increased deposition of melanin in the melanocytes of the basal and suprabasal layers), which is seen in 70% of women; dermal (macrophages with large amounts of melanin can be found in both the papillary and reticular layers of the dermis), which is seen in 10% to 15%; and a mixed form, which is seen in 2%.5,61 Although these pigmentary changes tend to fade completely within 1 year following pregnancy, they may persist (especially in dark-haired individuals).63,93,96

Melasma is associated with increased expression of α-melanocyte stimulating hormone in the involved skin area.93 There is a genetic predisposition toward development of melasma.5,100 Melasma is seen most frequently in women with dark hair and complexions, is exacerbated by the sun, and tends to recur (often with increased intensity) in subsequent pregnancies or with use of oral contraceptives.10 Melasma has also been reported occasionally in nonpregnant individuals who are not on oral contraceptives or other hormonal medications.54,93,96,118

Avoidance of sun tanning during pregnancy, use of hats to avoid facial exposure to sun, and use of sunscreens with sun protective ratings greater than 15 may reduce the severity of melasma (Table 14-1). Because melasma often fades spontaneously following pregnancy, treatment is generally limited to the less than 10% of individuals with persistent pigmentation postpartum.77 Various depigmenting formulas have been developed to treat persistent melasma, with varying success. These formulas tend to be relatively effective on epidermal-type melasma but have little effect on the dermal type. Treatment may need to be continued for 5 to 7 weeks before satisfactory results are achieved. Topical 2% to 5% hydroquinone with or without retinoic acid and corticosteroids has also been used postpartum, again with varying success. This treatment can result in complications such as hypopigmentation, hyperpigmentation, and contact dermatitis.5,10,93,96,118

Avoid suntanning during pregnancy or when using oral contraceptives.

Use broad-spectrum sunscreen (rating of 15 or greater).

Counsel regarding the risk of similar changes with oral contraceptives.

Counsel regarding alternative methods of birth control.

Counsel regarding use of sunscreen and protection from sun with sunscreen use following pregnancy.

Changes in connective tissue

Striae gravidarum (also called linear striae, striae distensae, or linear stretch marks) are linear tears in dermal collagen that are commonly seen during pregnancy. These markings initially appear as irregular, pink or purple, wrinkled linear streaks that gradually become white. Striae are most prominent by 6 to 7 months and occur in 50% to 80% of pregnant women.93 They appear initially over the abdomen oriented in opposition to skin tension lines and later on the breasts, thighs, and inguinal area. Striae are seen more frequently in younger women with greater total weight gain during pregnancy, obese women, and women with larger birth weight infants.12 In addition, there appears to be a familial tendency.5,77,86,93,111,118

Striae gravidarum usually fade following pregnancy but never completely disappear, remaining as depressed, irregular white bands. Some women report striae itching, although because both pruritus and striae formation are prominent over the abdominal area during pregnancy, these two phenomena may not be related. There is no effective treatment to prevent striae formation. Topical emollients and antipruritics may be used (see Table 14-1). However, the effectiveness of topical agents such as cocoa butter, vitamin E, tretinoin, and olive oil and of massage to prevent striae formation has not been substantiated in controlled studies.77,96,102,120 Two recent studies found that cocoa butter did not prevent striae gravidarum or reduce its severity.12,87

Striae gravidarum are believed to arise from hormonal alterations—especially of estrogens, relaxin, and adrenocorticoids—along with alterations in the dermal support matrix with stretching.87 The increased levels of estrogens, corticosteroids, and relaxin relax the adhesiveness between collagen fibers and foster formation of mucopolysaccharide ground substance, which causes separation of the fibers and striae formation. The increased glucocorticosteroids during pregnancy may decrease dermal fibroblasts and collagen synthesis. Mast cells, which contain hormonal receptors for estradiol, also increase. Mast cells release enzymes to lyse collagen.5,61,96,102,118

Vascular and hematologic changes

Vascular changes during pregnancy related to the integumentary system include development of spider nevi or angiomas, palmar erythema, nonpitting edema, cutis marmorata, purpura, hemangiomas, and varicosities. Purpura and scattered petechiae may be seen on the legs of some women and are due to decreased capillary integrity with increased hydrostatic pressure.5 These usually resolve postpartum. Vascular changes are a result of distention, instability, and proliferation of blood vessels mediated by changes in pituitary, adrenal, and placental hormones with increased release of angiogenic growth factors.61,63,96 Other alterations in the vascular and hematologic systems are described in Chapters 8 and 9.

Vasomotor instability.

Vasomotor instability during pregnancy may result in flushing, feelings of hot or cold, and cutis marmorata.5,44,89 Cutis marmorata is a transient bluish mottling of the legs that is exaggerated on exposure to cold. It arises from vasomotor instability secondary to elevated estrogens. Persistence postpartum is abnormal and may suggest underlying pathology such as collagen vascular disorder, systemic lupus erythematosus, or vasculitis. Other changes due to vasomotor instability during pregnancy include pallor, facial flushing, and heat and cold sensations. Purpura secondary to increased capillary fragility and permeability occurs during the last months of pregnancy in many women.96,118

Spider nevi.

Spider nevi (also called spider angiomas, spider telangiectases, or nevus araneus) are found in 10% to 15% of normal adults, in individuals with liver dysfunction, and in up to two thirds of pregnant women. These nevi are more common in white pregnant women (60% to 70% by term) than African-American pregnant women (10% by term).44 Spider nevi consist of a central dilated arteriole that is flat or slightly raised with extensive radiating capillary branches. They are most prominent in areas of the skin drained by the superior vena cava (i.e., around the eyes, neck, throat, and arms). The basis for formation has been related to increased estrogen, because these structures are seen more frequently both during pregnancy and with use of oral contraceptives. However, many individuals with spider nevi associated with liver disorders do not have elevated estrogen levels.61,118

Spider nevi generally appear between 2 and 5 months of pregnancy and may increase in size and number as pregnancy progresses. These structures tend to regress spontaneously and fade within the first 7 weeks to 3 months following delivery, although they rarely completely disappear. They may recur or enlarge during subsequent pregnancies. Unresolved spider nevi can be treated by pulse-dye laser or electrodesiccation therapy.93

Palmar erythema.

palmar erythema is seen with pregnancy, liver disease, estrogen therapy and collagen vascular diseases.93 Two patterns of palmar erythema are seen during pregnancy: erythema of hypothenar and thenar eminences, palms, and fleshy portions of the fingertips; and diffuse mottling of the entire palm. The latter form is more common and similar to changes seen with hyperthyroidism and cirrhosis. Palmar erythema generally appears during the first two trimesters and disappears by 1 week after delivery. This phenomenon has a familial tendency and is seen in approximately two thirds of white pregnant women and one third of African-American pregnant women. Spider nevi and palmar erythema often occur together, suggesting a common etiology generally believed to be elevated estrogen levels with increased skin blood flow.5,28,44,61,90,93,118 No treatment is needed. Palmar erythema resolves after delivery.

Nonpitting edema.

Increased vascular permeability and sodium retention due to the effects of estrogens and corticosteroids result in transient nonpitting edema of the face, hands, and feet during late pregnancy.44,89 In the lower extremities, this is aggravated by pressure from the growing uterus. Nonpitting edema occurs in the face, especially the eyelids in approximately 50% of women, and in the lower extremities in 70% and is not associated with preeclampsia.96,118 Although most pronounced in the morning, it usually improves during the day. Interventions for non-pitting edema during pregnancy are listed in Table 14-1. Vulvar edema may also be seen.

Capillary hemangiomas.

Pre existing capillary hemangiomas may increase in size during pregnancy.5,96 In up to one third of pregnant women, new hemangiomas appear by the end of the first trimester, with slight, slow enlargement during the remaining trimesters.44,118 New hemangiomas usually appear on the head and neck and are unusual elsewhere.96 Enlarged existing hemangiomas and new hemangiomas regress postpartum but may not completely disappear. Hemangioma development in pregnancy is related to elevated estrogen.118

Varicosities.

5,61,65,89,93,96,118 Varicosities develop in approximately 40% of pregnant women. Varicosities occur most commonly in the legs but may also appear in the pelvic vessels, vulva, and anal area with hemorrhoid formation. Varicosities arise from estrogen-induced elastic tissue fragility, vascular distension, relaxin-weakened collagen and elastin, increased venous pressure in the lower extremities and pelvis from pressure of the gravid uterus, and familial tendency for valvular incompetence. Varicosities generally regress postpartum but do not completely disappear. Thrombi are rare with leg varicosities but are more frequent with hemorrhoids. Hemorrhoids are discussed in Chapter 12.

Alterations in cutaneous tissue and mucous membranes

The most common mucous membrane alterations are changes in the vagina and cervix, which are seen in all pregnant women, and gingivitis, which is seen in many women. A less common oral finding is a cutaneous lesion of the gums known as angiogranuloma, or epulis. Epulis and gingivitis are discussed in Chapter 12. Increased flow to the nasal mucosa leads to rhinitis in up to one third of women.37 Jacquemier-Chadwick and Goodell signs are vascular changes that are early signs of pregnancy. Jacquemier-Chadwick sign is characterized by erythema of the vestibule and vagina; Goodell sign is characterized by increased vascularity of the cervix.61,63,96

Another cutaneous change during pregnancy is the development of or increase in the number of existing skin tags called molluscum fibrosum gravidarum (also called acrochordons or, if large, fibroepithelial polyps).5,77,90,96 These are soft, skin-colored or hyperpigmented skin tags, which are small (usually 1 to 5 mm), pedunculated fibromas that appear during the second half of pregnancy, primarily on the lateral aspects of the face and neck, upper axillae, groin, and between and underneath the breasts. The cause of fibromata molle is unknown but is thought to be hormonal. These skin tags are more common in the second half of pregnancy, when they may increase in size and number. These growths may regress or clear spontaneously following delivery, although many remain. Remaining skin tags can be excised.61,63,77,90,93,96,118

Alterations in secretory glands

Activity of the sebaceous, apocrine, and eccrine glands of the skin is altered during pregnancy. Sebaceous gland activity is generally reported to increase during pregnancy.5,90,118 Many pregnant women report that their skin, especially on the face, feels “greasy.” Some women may develop acne, often for the first time, although women with existing acne may or may not experience worsening of the acne.5,61 These changes are due to increased ovarian and placental androgens.61,93 Montgomery tubercles (small sebaceous glands on the areola) enlarge, beginning as early as 6 weeks’ gestation. Changes in Montgomery tubercles and the breasts are described in Chapter 5.

Apocrine sweat gland activity decreases during pregnancy, possibly as a result of hormonal changes.5,118 Eccrine sweat gland activity increases gradually during pregnancy, possibly because of increased thyroid activity along with increased body weight and metabolic activity.89,90,118 Because eccrine glands are important (along with the cutaneous blood vessels) in thermoregulation at the skin surface (see Chapter 20), their increased activity reflects dissipation of excess heat produced by the increased metabolic activity of the pregnant woman and her fetus. Increased eccrine activity during pregnancy can lead to miliaria (prickly heat) or dyshidrotic eczema.5,61,118 Palmar sweating is decreased in pregnancy, even though this is an area where eccrine glands are highly concentrated. The basis for this is unclear but may be related to increased thyroid or adrenocortical activity.5,28,61 Interventions are listed in Table 14-1.

Alterations in hair growth

Estrogen increases the length of the anagen (growth) phase of hair follicles during pregnancy (see the Hair Loss section under Postpartum Period). This results in increased hair loss postpartum. The diameter of the hair shaft also thickens by late pregnancy in most women.5,31,83 A mild hirsutism may develop, usually beginning around 20 weeks, with increased growth of hair on the upper lip, chin, and cheeks and in the suprapubic midline. Fine new hairs usually disappear by 6 weeks postpartum, but the coarser hairs usually remain.13,61,77,93,96,113,118

During late pregnancy and the early postpartum period, some women develop hair loss with frontoparietal recession of the hairline similar to changes seen in male-pattern baldness. This loss is rare and is usually associated with complete regrowth and not with later development of female-pattern alopecia.61,96

Alterations in the nails

Changes in fingernails and toenails during pregnancy are uncommon and of unknown pathogenesis. Nail changes occur as early as 6 weeks and include transverse grooves, increased brittleness, distal separation of the nail bed (onycholysis), whitish discoloration (leukonychia), and subungual keratosis. These changes regress after delivery.5,61,77,90,93,118 A faster toenail growth rate has been reported by some women during pregnancy, possibly due to increased peripheral blood flow due to estrogens, along with coarsening of the nail texture.89

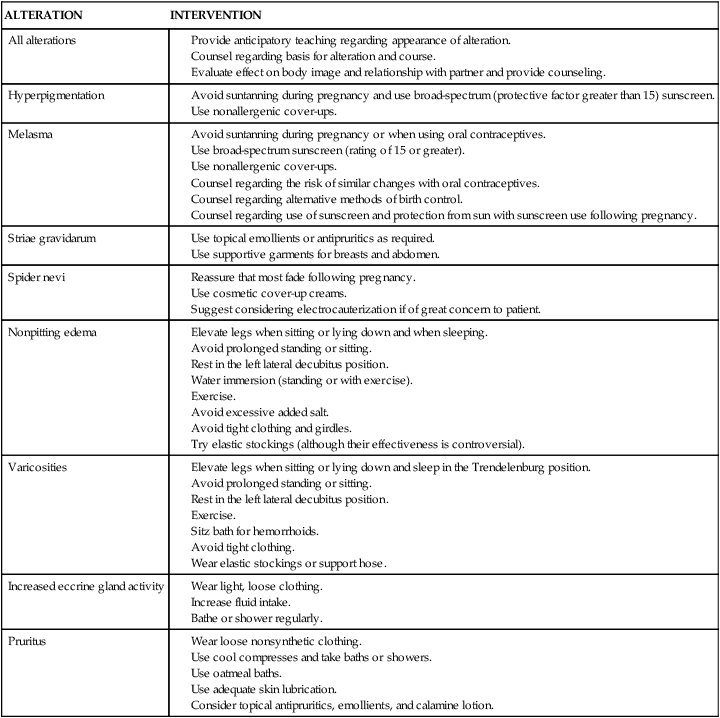

Pruritus

Pruritus is the most common cutaneous symptom during pregnancy.5 The itching may be localized, especially over the abdomen during the third trimester, or generalized. Abdominal pruritus at the end of the first trimester may be an isolated finding or an early sign of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with or without associated jaundice or one of the other specific dermatoses of pregnancy (Table 14-2). Pregnancy-associated pruritus always clears after delivery but may recur in subsequent pregnancies or with use of oral contraceptives.93 Pregnant women with pruritus should also be assessed for other skin disorders, including pregnancy dermatoses, contact dermatitis, and drug reactions.5,93,118

Table 14-2

| DISORDER* | INCIDENCE | ONSET AND ETIOLOGY | CHARACTERISTICS | LOCATION OF ERUPTIONS | COURSE | OTHER MATERNAL FINDINGS | EFFECT ON FETUS/NEONATE |

| Pemphigoid gestationis (herpes gestationis) (11, 20, 93, 96, 97, 98) |

Usually second and third trimesters

Can appear as early as 2 weeks’ gestation or up to 2 weeks postpartum (20%)

May clear toward end of pregnancy and, then exacerbate postpartum

Etiology: autoimmune disorder with production of anti-human leukocyte antigen (HLA) autoantibodies against basal membranes that hold the epidermis and dermis together seen in many women

*Numbers in parentheses refer to citations in reference list.

Postpartum period

Some of the changes in the integumentary system and its associated structures clear spontaneously following delivery; other alterations may regress or fade but do not disappear completely (see previous section for specific skin changes). Hyperpigmentation fades in many women; however, these changes may remain, especially in women with darker skin and hair. In addition melasma may persist for months postpartum in up to 30% of women.93 After delivery, striae gravidarum and spider nevi fade and capillary hemangiomas, varicosities, and skin tags regress. However, these changes may not completely disappear.61,93,96 Increased body and facial hair usually regresses by 6 months postpartum; thinning or regression of the hairline may not reverse completely.77 Alterations in hair growth during pregnancy result in an increased hair loss during the postpartum period in many women.

Hair loss

The scalp contains approximately 100,000 hair follicles. Hair fibers in each follicle independently cycle through three stages: anagen, catagen, and telogen. The anagen or growth stage lasts for 3 to 4 years and is characterized by intense metabolic activity. In this stage, hair grows an average of 0.34 mm/day.93 Catagen is a transitional stage that lasts several weeks. During this stage, metabolic activity and growth slow as the hair bulb is retracted upward into the follicle. Growth of the hair fiber stops during telogen (resting stage). Eventually a new hair bulb begins growing, which ejects the previous hair.93 Normally about 80% of hair follicles are in the anagen stage and 15% to 20% of hair fibers are in the telogen stage, with about 100 to 150 hairs shed per day.96

Under the influence of estrogen during pregnancy, the rate of hair growth slows and the anagen stage is prolonged. This results in an increased number of anagen hairs and a decrease in telogen hairs to less than 10% during the second and third trimesters. During the postpartum period, with the decline in estrogens, these anagen hairs enter catagen and then telogen and are shed. Since there are more anagen hairs (and thus eventually telogen hairs) than usual, most postpartum women experience an increased hair loss, beginning 4 to 20 weeks after delivery. During this time, 30% to 35% of the hairs may enter telogen. Generally, complete regrowth occurs by 4 to 6 months in two thirds of women and by 15 months in the remainder, although the hair may be less abundant than before pregnancy.13,93,96,113 Telogen effluvium is the term used to describe the rapid transition of hair follicles into the telogen stage following delivery, surgery, or severe emotional or physical stress.93,96,118

Clinical implications for the pregnant woman and her fetus

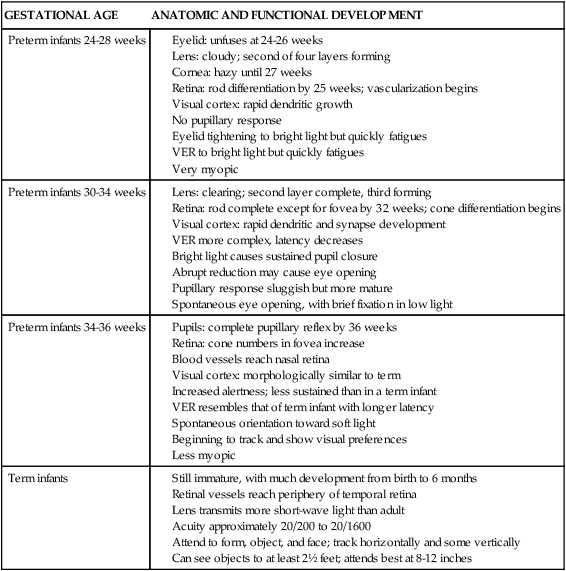

The physiologic changes in the integumentary system during pregnancy and after delivery are common experiences for many women. These changes seldom significantly alter the function or structure of the integumentary system and are considered by some to be minor nuisances.96 However, these changes may have significant psychological and cosmetic implications for the pregnant woman and can contribute to alterations in body image. General interventions include anticipatory counseling, education, and reassurance (see Table 14-1).

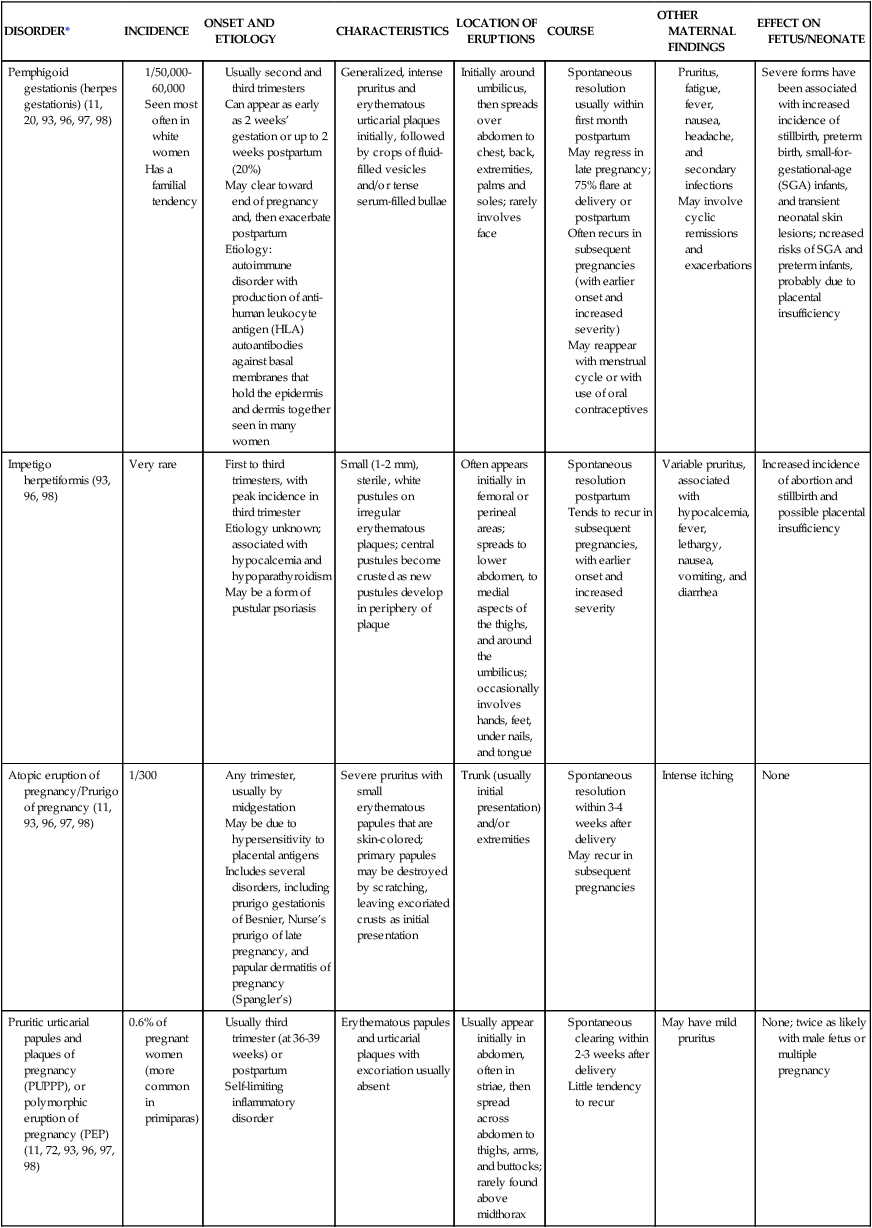

Dermatoses associated with pregnancy

In addition to the normal physiologic skin changes associated with pregnancy, there are several integumentary disorders that are unique to pregnancy. Specific dermatoses seen only during pregnancy include pemphigoid gestationis, impetigo herpetiformis, atopic eruptions of pregnancy/prurigo of pregnancy, pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP) or polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.61,93,96 Several of these disorders have been associated with increased fetal morbidity and mortality (see Table 14-2). Most of these disorders resolve spontaneously within a few weeks after delivery, but can recur with subsequent pregnancies.93

The etiology of some of these disorders is unclear, although others have a hormonal or immunologic basis. For example, pemphigoid gestationis is an autoimmune disorder with production of anti–human leukocyte antigen (HLA) autoantibody against basal membranes that hold the epidermis and dermis together (see Table 14-2).20,40,97 There has sometimes been confusion in classifying some of the rarer dermatoses, in that much of the literature regarding these disorders involves reports of small numbers of women, which may represent different variations of the same disorder. Treatment involves use of topical emollients, antipruritics, cold compresses, oatmeal baths (for relief of itching), and topical steroids. In women with moderate to severe eruptions, systemic steroids and antihistamines may be used. Cautions must be used in prescribing these and other dermatologic agents during pregnancy as some, such as retinoic acid, are teratogenic (see Chapter 7) and thus are contraindicated in pregnancy. There are limited data for most other agents on their use in pregnancy. Thus risk-benefit must be carefully evaluated.17,93

Effects of pregnancy on pre existing skin disorders

The effects of pregnancy on pre existing skin disorders varies from no effect to marked improvement or worsening.28,93,96,118 With disorders such as psoriasis, eczema, contact dermatitis, and acne vulgaris, this range of effects during pregnancy has been described within the same disease in different women.93 Neurofibromas increase in size during pregnancy and new tumors may appear.93 The effect of pregnancy on malignant melanoma is also variable.22,93 No significant effect on survival in women with a diagnosis of localized melanoma (stage I or II) during pregnancy was found in an analysis of six case controlled studies.27 Decreased survival or shorter disease-free survival for pregnant women with recurrent melanoma is reported in some studies.22,27 Effects of pregnancy on other integumentary disorders are reviewed in the literature.93,96

Summary

The effects of pregnancy on the integumentary system include physiologic changes in the skin and its appendages that are experienced by most pregnant women, skin disorders that are unique to pregnancy, and possible changes in pre existing skin disorders. Nursing management of the pregnant woman in relation to these effects includes preparation for the physiologic changes and their sequelae, and reassurance and support, as well as assessment for the specific dermatoses of pregnancy that are associated with maternal systemic symptoms and, if severe and untreated, with increased fetal mortality and morbidity. Clinical recommendations related to changes in the integumentary system during pregnancy are summarized in Table 14-3.

Table 14-3

Recognize the usual changes involving the skin, hair, nails, and sebaceous and sweat glands during pregnancy and the postpartum period (pp. 484-488).

Provide anticipatory teaching regarding the usual alterations in the skin and its appendages during pregnancy (pp. 484-488).

Counsel pregnant women regarding the basis for integumentary alterations and their usual course, and whether or not the change will regress postpartum (pp. 484-488).

Evaluate the effect of integumentary changes on the woman’s body image and relationship with her partner and provide counseling (pp. 484-488).

Counsel women regarding the potential for integumentary alterations during subsequent pregnancies or with use of oral contraceptives (pp. 484-488, Table 14-1).

Recommend specific interventions to reduce or ameliorate the effects of integumentary changes (Table 14-1).

Recognize the specific dermatoses associated with pregnancy (pp. 488, 491 and Table 14-2).

Avoid use of isotretinoin in pregnant women or sexually active women of childbearing age who are not using reliable, highly effective forms of birth control (p. 491 and Chapter 7).

Counsel women with chronic integumentary disorders regarding the effect of pregnancy on their disorder (p. 491).

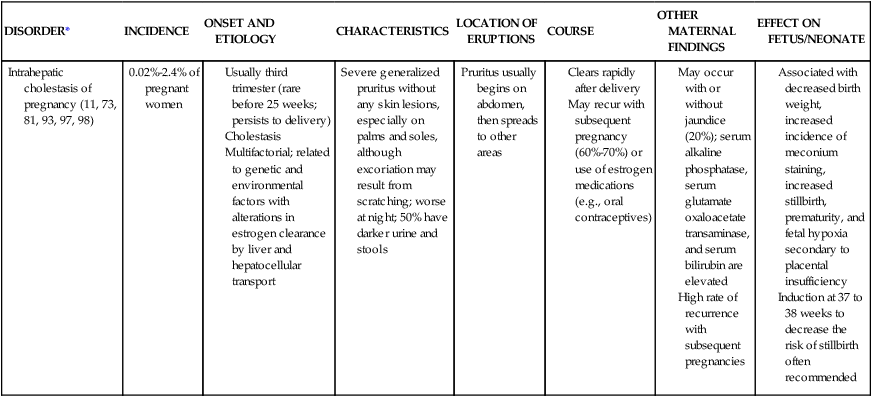

Development of the integumentary system in the fetus

Anatomic development

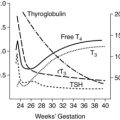

The basic structure of the skin develops during the first 60 days of gestation. Around the time of transition from embryo to fetus, the skin undergoes a series of rapid morphologic changes, including keratinization of the epidermal appendages (around 15 weeks) and interfollicular epithelium (around 22 to 24 weeks).19 By the third trimester, the structure of the skin is similar to that of the adult. However, its barrier properties are still immature, especially in the infant born before term.19 Further maturation of the skin occurs within the first weeks after birth and during infancy.9,82,106,114

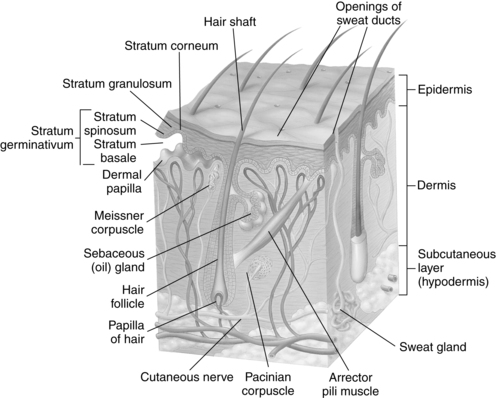

The skin consists of the epidermis and dermis with an underlying subcutaneous layer (Figure 14-1). The epidermis consists of an outer stratum corneum, stratum granulosum, and the stratum germinativum, which consists of the stratum spinosum, and stratum basale (adjacent to the epidermal-dermal junction). The basal layer contaikns melanocytes (pigment-producing cells) and keratinocytes. Keratinocytes, the major cell of the epidermis, develop from stem cells in the basal layer and migrate outward to cornify the outer layer.35 The stratum corneum is the barrier layer and consists of keratinocytes linked by lipids. Underneath the epidermis lies the dermis, formed from fibrous protein, collagen, and elastin fibers woven together. The dermis contains the nerves and blood vessels that nourish the skin cells and carry sensations from the skin to the brain (see Figure 14-1). Mechanical properties of the dermis include tensile strength, compressibility, resilience, and elasticity.19 The subcutaneous layer is composed of fatty connective tissue that provides insulation and caloric storage.71 The epidermis and dermis, along with their vascular and neural networks, develop concurrently.

Epidermis

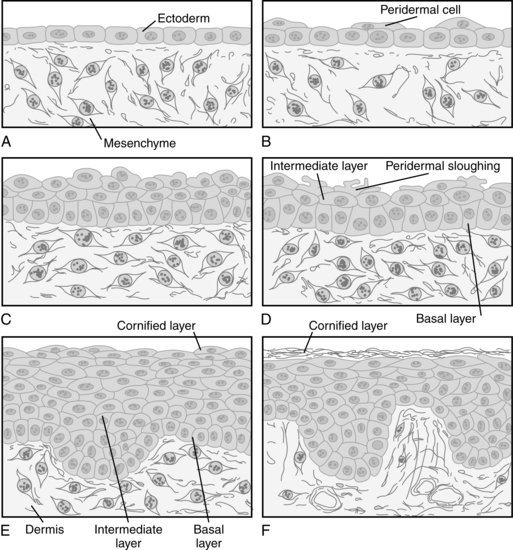

Development of the epidermis “is characterized by coordinated establishment of increasing numbers of cell layers concomitant with expansion of skin surface area and cellular (keratinocyte) differentiation.”19 The epidermis develops from undifferentiated ectoderm at 5 to 8 weeks.49 It initially consists of a single layer of cuboidal cells that develop from the outer germinal stratum (surface ectoderm) and can be identified during the third week of gestation (Figure 14-2, A). By 30 to 40 days, two layers are seen: the inner basal layer and the outer periderm (see Figure 14-2, B).35,66 The definitive epidermis develops from the basal layer.

The periderm is a transient embryonic layer that disappears in the second half of gestation.19,66 The periderm serves as the protective barrier for the embryo and fetus until the end of the second trimester and forms part of the vernix caseosa.49,66 Until the underlying layers develop, active transport occurs across the periderm between the amniotic fluid and the embryo; thus the periderm acts as a nutrient interface with amniotic fluid.49,66 The outer border of the periderm rapidly proliferates between 11 and 14 weeks with formation of blebs and microvillus projections, which are coated with very fine filaments.35,49 Development of the epidermis is under the influence of epidermal growth factor (EGF); matrix adhesion is thought to be mediated by actin-associated α6B4 integrin.49,66 Cell surface receptors for EGF are found on both the basal layer and periderm.19

By 60 days, the epidermis has three layers (see Figure 14-2, D): the basal layer, an intermediate layer, and the superficial periderm. The intermediate layer becomes more complex by the end of the fourth month, when the epidermis has stratified. The epidermal strata are the stratum basale; the stratum spinosum, which is made up of large polyhedral cells connected by tonofibrils; the stratum granulosum, which contains small keratohyalin granules; and the stratum corneum, which is made up of dead cells packed full of keratin.101 Peridermal cells are replaced continuously until regression begins around 18 weeks. Shedding of peridermal cells begins in the scalp, plantar surfaces, and face, areas where keratinization first begins.16 The periderm gradually undergoes regression and apoptosis as the stratum corneum and vernix caseosa develop (see Figure 14-2, F ). The epidermis is keratinized in skin appendages at 11 to 15 weeks and in the interfollicular area at 22 to 24 weeks.19 As stem cells in the stratum germinativum proliferate, they develop down growths (epidermal ridges) that extend into the dermis.

Protoplasmic fibers and cellular bridges begin to form. These make up the stratum spinosum, eventually protecting the neonate from dehydration and reducing permeability to noxious substances. From 11 to 18 weeks, this layer has an abundance of glycogen to provide energy for growth.14 Glycogen reserves decrease around 18 weeks.49 Keratogenic structures become evident, leading to regional differences in epidermal thickness. By 24 weeks, the skin has largely concluded its period of histogenesis and moves into a period of structural and functional maturation.19

Ridge patterns (future fingerprints) are genetically determined, although modified by the intrauterine fluid environment, and can be seen on the surface of the hands and soles of the feet.76 These ridges are seen between 11 and 17 weeks in the hands and between 12 and 18 weeks in the feet.14 Chromosomal abnormalities such as Down syndrome modify the ridge pattern.

Keratins are produced in the stratum germinativum by 2 months and increase rapidly as the epidermis stratifies.21 Keratinocytes are arranged in columnar fashion adjacent to the dermis.19 Keratinocyte maturation is stimulated by several different growth factors, including EGF, transforming growth factors, insulin-like growth factors, and fibroblast growth factor.14 The first signs of keratinization are seen by 22 to 24 weeks.16,19

As replacement keratinocytes mature, they rise and move through the stratum granulosum and acquire keratohyalin granules. As they continue to travel upward, the keratinocytes lose 85% of their water content and their organelles, which are replaced by keratin.14,19,100 As the keratinocytes dehydrate and flatten, they adhere to each other to form a tough, resilient, and relatively impermeable membrane—the stratum corneum.90 Transit time for a keratinocyte from the basal layer to the uppermost stratum takes approximately 28 days.76 By 5 months, the periderm is completely shed, mixing with secretions from the sebaceous glands to form the vernix caseosa.101

The stratum corneum becomes thicker and more organized with increasing gestation, but it is not well defined until 23 to 24 weeks’ gestation.16,50 The stratum corneum is more fully developed by 34 weeks, but still immature compared to older children and adults.9,32,82,106,114 Formation of the stratum corneum may be facilitated by vernix caseosa.50 At 28 weeks, the stratum corneum consists of two to three cell layers, increasing to 15 or more layers (similar to the adult) after 32 weeks.21

During embryonic development, primitive Langerhans cells and melanocytes migrate into the epidermis.49 Early in the second trimester, the epidermis is invaded by cells from the neural crest called melanoblasts or dendritic melanocytes because of their long processes much like dendrites. These cells come to lie adjacent to keratinocytes at the dermal-epidermal junction. By midgestation the melanoblasts have been converted to melanocytes, with formation of characteristic organelles or melanosomes and pigmentary granules, and gradually increase to adult numbers of cells.19 Melanocytes transport melanin along their dendrites, from which it is taken up by the basal cells.14,49

Melanin production and transfer into surrounding keratinocytes occur by 4 to 5 months.21 Production of melanin remains low in newborns, who have less pigmentation than older children.66 Melanin is responsible for skin color; variations are due to the amount and color of the melanin. Prenatal pigmentation is seen in the nipples, axillae, and genitalia and around the anus. Racial variations are seen not in the number of melanocytes, but rather in the size, shape and activity of these cells and in the number of pigmentary granules per cell.14,49 Melanin protects deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) from ultraviolet radiation damage. Langerhans cells migrate into the epidermis by week 8, begin to develop CD1 antigens by 60 days, and increase markedly during the third trimester. Although their function is not entirely understood, these cells have phagocytic activity and are involved in skin host defense mechanisms.14,19,21,49,66

Alterations in development of the epidermis include palmoplantar keratodermas and the ichthyoses, including collodian babies (infants are covered by a shiny cellophane-like membrane) and infants with harlequin ichthyosis (characterized by thick, armor-like scales with fissures).19,49,95 These disorders are characterized by a defective epidermal barrier with abnormalities in formation of the keratinocytes and a defective desquamation process. Many forms of these disorders have a genetic basis.95,104

Dermis

Lying below the epidermis is the metabolically active dermis, which exerts a symbiotic and controlling influence on the epidermis. The dermis is composed of connective tissue, amorphous ground substance, free cells, nerves, blood vessels, and lymphatic vessels (see Figure 14-1). The connective tissue consists of collagen (90%) and elastic and reticular fibers embedded in proteoglycans (ground substance) consisting of a protein with glycosaminoglycans such as hyaluronic acid and dermatan sulfate (chondroitin sulfate B).49 The fibroblasts are the most numerous cells, producing collagen and glycosaminoglycans. Mast cells, histiocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils are all present in the dermis.

The dermis originates from the somatopleuric mesenchyme and the somites.35,76 Initially the dermis is a loose aggregate of interconnected mesodermal cells that secrete a liquid intercellular matrix rich in glycogen and hyaluronic acid.26 Hyaluronic acid promotes cell migration.19 With increasing age, dermatan becomes more prominent and dermal water content decreases.49 The dermis in the eighth-week embryo has undifferentiated cells, appears myxedema-like (as seen in the umbilical cord), and contains no fibrils.35 Eventually three layers form: superficial (adjacent to the epidermal basement membrane), papillary, and reticular.49 The latter two layers are present by 4 months’ gestation. Between 8 and 12 weeks, the fibroblasts form, leading to differentiation of connective tissue. During this time, fibrillae appear between dermal cells, which continue to grow, developing a network of collagenous and elastic fibers.76,101 The fetal dermis contains all of the different types of collagens seen in the adult, although type III collagen is found in greater proportions in the fetus.19 Elastin fibers are first seen around 20 weeks.49

With further maturation the dermal layer moves from an organ abundant in water, sugars, and hyaluronidase to one enriched with collagen and sulfated polysaccharides.19,35 Immature skin may be edematous, a sign of the excess water and sodium contained within it and the continued immaturity of this system. Development of this fibrous matrix continues after birth, becoming thicker and denser.7

Capillaries and lymph vessels form simultaneously with the skin. Initially the blood vessels are simple endothelium-lined structures from which new capillaries grow. Two vascular networks are seen in skin by 60 to 70 days, a superficial (subpapillary plexus of adult) and a deeper layer (adult reticular network).49 The subcapillary vascular network is disorganized at birth and matures in the first year.19,32,84

The dermal-epidermal junction is critical for skin integrity. The junction begins to develop in the first trimester as the basal lamina, hemidesmosomes, anchoring fibrils, and anchoring filaments develop.19 This junction is still immature in very low–birth weight infants and is not fully developed until about 6 months postbirth.21 During the third and fourth months, the corium proliferates to form papillary projections that extend into the epidermis. These irregular structures are called the dermal papillae. Some contain capillary loops that nourish the epidermis, and others have sensory nerve endings.

Disorders of the dermal-epidermal junction include various forms of epidermolysis bullosa (EB) that result in friction-induced cutaneous blistering, mucosal erosions, and wounds that do not heal.19,49,95 EB is a group of inherited disorders classified according to the cleavage plane of the blisters. Major types are EB simplex, junctional EB, and dystrophic EB, each having multiple subtypes.19,104

Adipose tissue

The hypodermis or subcutaneous tissue is a passive tissue that forms from mesenchymal cells. Subcutaneous tissue, which has a lobar structure surrounded by connective tissue, has its own blood supply. The first cells can be seen around 14 weeks; initially they are cytoplasmic and contain no fat droplets. With maturation, single or multiple fat granules develop.76 Most adipose tissue is deposited in the third trimester.

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) differentiates from the hypodermal primitive cells between 26 and 30 weeks.24,80 BAT accumulates in the neck; underneath the scapulae; and in the axillae, mediastinum, and perirenal tissues. BAT is critical for nonshivering thermogenesis, the major method of neonatal heat production (see Chapter 20).

Cutaneous innervation

In the third month of gestation, free nerve endings connect with the papillary ridges of the finger and toe pads. By term these nerve endings are exceptionally well developed in the perioral area around the lips and sucking pads. Specialized nerve endings are less well developed and continue their maturation throughout infancy.14,76

Epidermal appendages

The structures that result from invaginations of epidermal germinative into the dermis or from the epidermis itself are the epidermal appendages.49,66 These include the eccrine sweat, sebaceous, and apocrine sweat glands; lanugo and hair; and the nails.

Hair and nails.

The hair is an epidermal derivative that develops under mesodermal induction. Development of the hair follicle begins in the head area and then spreads caudally and ventrically.66 All hair follicles develop prior to birth.39 Follicular placodes can be seen by 75 to 80 days.66 Hairs are first seen at 10 to 12 weeks.14 Initially the hairs develop from solid epidermal proliferations, cylindrical downward growths of the stratum germinativum into the dermis, where dermal cells condense into dermal papillae (inducer cells). The base of these growths becomes the club-shaped hair bulb. The epithelial cells of the hair bulb form the follicular germinal matrix, which later gives rise to the hair itself. The lower part (dermal papilla) of the hair bulb becomes rapidly invaginated by the mesoderm, in which vessels and nerve endings develop. This forms the pilary complex.14,18,21,76,101

The central cells of each down growth (germinal matrix) form the hair shaft. As the epithelial cells continue to proliferate, the hair shaft is pushed upward toward the epidermal surface. The peripheral cells (epithelial hair sheath) become cuboidal and form the wall of the hair follicle.18,101 By the end of the third month, extensive fine hairs (lanugo) have begun to develop. Hair on the eyebrows, upper lip, and chin regions appears around 16 weeks and is plentiful by 17 to 20 weeks.14,53 Lanugo is shed before or after delivery and replaced by shorter, coarser hairs (vellus hairs) from new follicles.

Fetal scalp hair is visible by 19 to 21 weeks and the first complete hair cycles (anagen growth to catagen degeneration to telogen resting phases) are seen by 24 to 28 weeks with initiation of short catagen/telogen phases.19,39,66 The onset of the hair cycle/anagen is mediated by papillary-derived insulin-like growth factor-1, fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2, FGF-7, substance P, corticotropin, and capsaicin.39 Hair growth is also influenced by other substances such as growth hormones, thyroid hormones, androgens, glucocorticoids, retinoids, and prolactin.39 With subsequent hair cycles, the diameter of the hair shaft increases.

Melanoblasts migrate into the hair bulb and differentiate into melanocytes between 6 and 7 weeks.39 During the second half of gestation, melanogenesis is active in the fetal hair follicle. Hair patterning and growth are influenced by central nervous system (CNS) development. Infants with neurologic abnormalities may have abnormal hair whorls or alterations in the direction of hair growth or amount of hair.36 These differences may be related to tension on the epidermis during the period of hair follicle formation.14

Nails appear at 8 to 10 weeks and are the first tissue to keratinize, beginning around 11 weeks, and are completely formed by 5 months. During the remainder of gestation, nails continue to elongate.19,49,66

Sebaceous glands.

The sebaceous glands form within the epithelial wall of the hair follicle, usually as a small out-pouching of ectodermal cells that penetrate the surrounding mesoderm at the hair follicle neck at 13 to 16 weeks.66 These outgrowths branch to form the primordia of the glandular alveoli and ducts. The center cells degenerate to form a fatlike substance (sebum), which is secreted into the hair follicle or directly onto the skin. The sebum mixes with the desquamated peridermal cells to help form the vernix caseosa (see section on Vernix Caseosa).49,53,101 Sebum is thought to be responsible for neonatal “acne.”66

Most of the sebaceous glands differentiate at 13 to 15 weeks’ gestation, immediately producing sebum in all hairy areas.49 Each gland usually consists of several lobules filled with disintegrated cells that are extruded into an excretory duct. The rapid growth during gestation and immediately after birth is due to circulating maternal androgens and, possibly, endogenous steroid production by the fetus.53

Arrector pili muscle.

Some of the surrounding mesenchymal cells differentiate to form the arrector pili muscle, which is made up of smooth muscle fibers that attach to the connective tissue sheath of the hair follicle and dermal papillary layer. These muscles are located a short distance from the follicular wall in a region where the ground substance is metachromatic. The connection of the muscle root sheath is a secondary event, with innervation occurring later.101

Eccrine and apocrine glands.

The sweat glands are also appendages of the epidermal layer. There are three types of sweat glands. Only two are discussed here; less is known about the third type (apoeccrine), which develops in adolescence and is found only in adult axillae. The eccrine glands develop first and are distributed throughout the cutaneous barrier. The apocrine glands develop later and are more specialized. Both are down-growths of solid cylindrical epidermal tissue that invade the dermal layer and are innervated by sympathetic cholinergic nerves. No additional glands form after birth.49

The eccrine glands appear in the sixth week of embryogenesis and are innervated by the sympathetic nervous system. The epidermal tissue for this gland is more compact than that of the hair primordia, and it does not develop mesenchymal papillae. Once the bud reaches the dermis, it elongates and coils, developing a lumen at around 16 weeks.19,76 Eccrine glands retain two layers of cells once the lumen is formed. The inner layer is made up of the lining and gland cells; the outer layer is specialized ectodermal smooth muscle cells that aid in the expulsion of secretions. Eccrine glands are seen on the volar surface of the hand at 3.5 months and in the axillae by 5 months.18 All eccrine glands are present by 24 to 28 weeks, but do not function until after birth.18,19

The apocrine glands are large organs that develop after the eccrine glands. They are confined to the axillae, pubic area, and areolae of the mammary glands. Apocrine glands originate from and empty into the hair follicles, just above the sebaceous glands. By 7 to 8 months’ gestation, they become transiently functional and produce a milky white fluid containing water, lipids, protein, reducing sugars, ferric iron, and ammonia.49,76 Decomposition of this fluid by skin bacteria produces a characteristic odor.

Vernix caseosa

“At birth the human infant is covered with a complex material [vernix caseosa] possessing endogenous anti-infective, antioxidative, moisturizing and cleansing capabilities.”49 Vernix caseosa forms as a superficial fatty film after 17 to 20 weeks. It is made up of sebaceous gland secretions and desquamated cells of the periderm or stratum corneum cells and is rich in triglycerides, fatty acids, cholesterol, ceramides (lipid-signaling molecules, which have a role in water regulation and barrier function), and unsaponified fats.48,100 Vernix is composed of 80.5% water, 10.3% lipids, and 9.1% proteins.52 After 36 weeks, the vernix thins and begins to disappear. Pulmonary surfactants in amniotic fluid mediate detachment of the vernix from the skin.49 Both preterm and postterm infants have less vernix at birth than term infants. At term, the heaviest layers are found on the ears, shoulders, sacral region, and inguinal folds. The vernix has a tendency to accumulate at sites of dense lanugo growth.

The vernix is a biofilm that covers the fetus until birth and provides insulation of the skin during gestation, acts as an emollient to provide protection from amniotic fluid maceration, and minimizes friction at delivery. Vernix also prevents the loss of water and electrolytes from the skin to the amniotic fluid and contains antioxidants such as alpha-tocopheral.94,108,115 Vernix has antimicrobial properties such as antifungal activity, opsonization capacity, inactivation of parasites, and protease inhibition that may protect the fetus from chorioamnionitis and contains substances such as lysozyme, lactoferrin, and defensins.94,108,112,115 Vernix also optimizes stratum corneum hydration and may play a role in fetal wound healing.32,50 Fetal wound healing differs from that of the adult (Table 14-4) and often the fetus heals without scarring.21

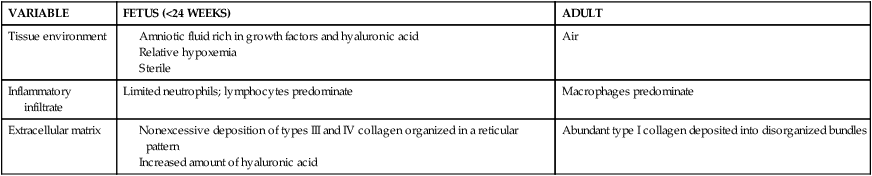

Table 14-4

Comparison of Fetal and Adult Wound Repair

| VARIABLE | FETUS (<24 WEEKS) | ADULT |

| Tissue environment |

From Cohen, B.A. & Siegfried, E.C. (2012). Newborn skin: Development and basic concepts. In C.A. Gleason, & S. Devaskar (Eds.). Avery’s Diseases of the newborn (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders, p. 1364.

Functional development

Intrauterine physiologic functioning of the skin is dependent upon the growth, development, and maturation of the fetus. The fluid environment of the uterus also has an impact on cutaneous functioning. The amniotic fluid ensures an even distribution of temperature and protection from trauma and injury, allowing for symmetric development of the fetus and providing a medium in which the fetus can move. Amniotic fluid composition and exchange are discussed in Chapter 3.

Neonatal physiology

The physiology of the integumentary system in the neonate includes the barrier properties of the skin, permeability, transepidermal water loss, heat exchange between the environment and the infant, collagen instability, and the protective mechanisms of the skin. Along with these functions, the skin is the most sophisticated sensory organ system in the neonate. It accounts for about 13% of body weight in preterm infants, decreasing to 3% by adulthood.47 The neonate obtains the vast majority of its information about the environment through the skin. Tactile development is discussed in Chapter 15.

Transitional events

In the first hours following delivery, the infant develops an intense red color, which is characteristic of the newborn. This may remain for several hours; however, exposure to the cooler environment usually leads to a bluish mottling, which dissipates quickly upon warming. Newborn skin is relatively transparent and smooth looking and is soft and velvety to touch. This appearance is due to the lack of large skin folds and skin texture. The epidermis and stratum corneum of infant skin are thinner than in adults with smaller corneocytes and keratinocytes, more densely packed glyphics (island-like structures within the stratum corneum), and a denser microrelief network.107 Localized edema may be seen, especially over the pubis and the dorsa of the hands and the feet. This edema decreases within the first few days of life, after which the skin lies loosely over the entire body.

Newborns have less pigmentation than older children due to decreased melanin production (melanin acts as an ultraviolet light filter). The increased pigment in the ear tips, scrotum, linea alba, and areolae are due to maternal and placental hormones.49 Because of their lack of pigmentation, young infants are more susceptible to damage from ultraviolet light.107

Lanugo hair is shed after birth and replaced with vellus hair.18 The newborn has 10 times as many hair structures per unit of skin surface as adults.106 At term hair follicles on the scalp are in different stages of the hair cycle depending on their location. Frontal and parietal hairs are moving to telogen; occipital are in anagen and move to catagen/telogen by 8 to 12 weeks post birth.13 At birth the synchrony of hair growth (anagen) and hair loss (telogen) is transiently altered so hair may become thick and coarse or be lost (temporary alopecia).49 The postnatal hair cycle lasts 2 to 6 months; length of an individual hair is determined by the length of the anagen phase.39 Hair on the scalp at birth reflects metabolic activity from week 28 on and therefore may be useful for assessment of prenatal toxin exposures.39

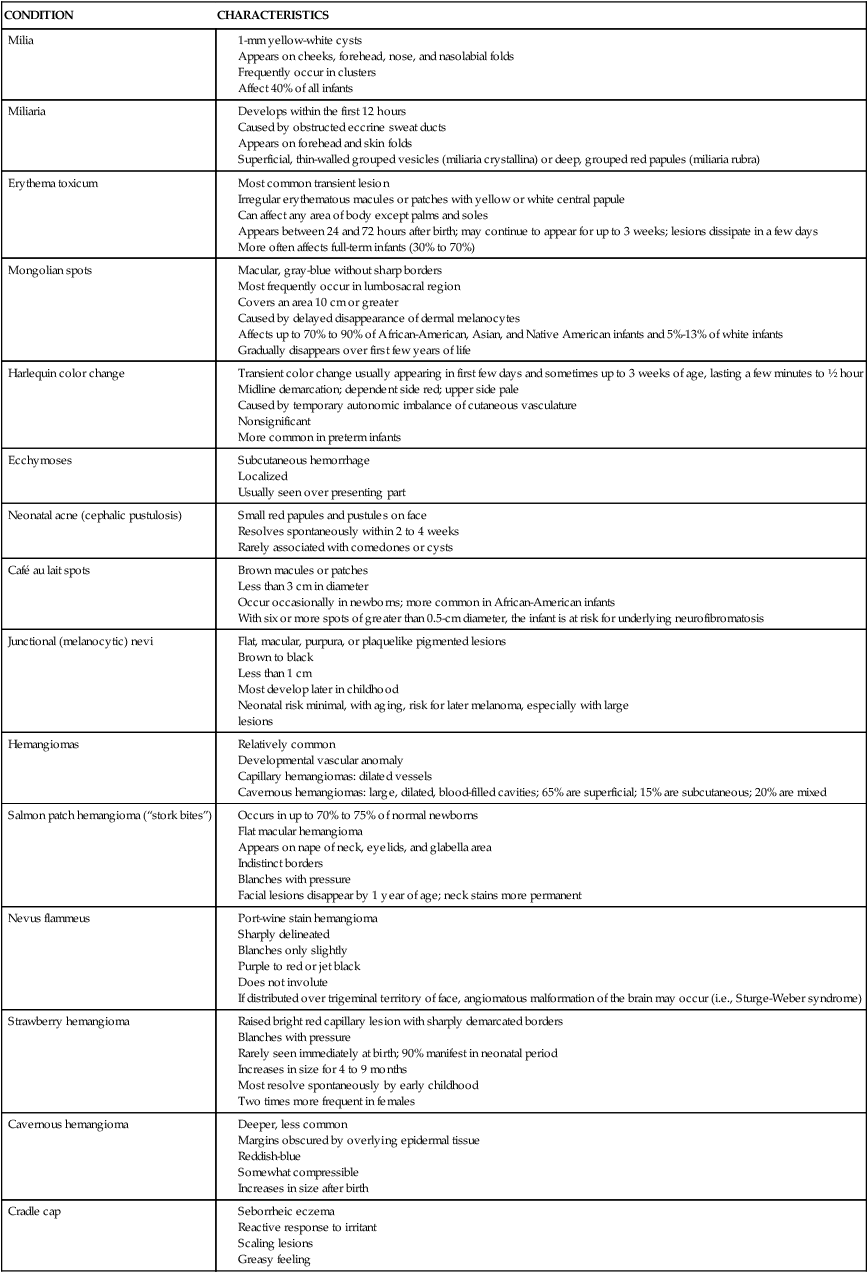

Initially the skin is covered with the yellow-white vernix caseosa. This insulating layer is lost with the bathing that occurs in the nursery. Removal results in exposure of the stratum corneum to the much drier postnatal environment, with desquamation of the upper layers of the stratum corneum. After the first week, visible desquamation gives way to normal proliferation and flaking, signaling adaptation. This drying out of the skin is part of the natural maturational process. Any interference in this keratinization (e.g., use of lotions or creams) only delays the development of an effective barrier and prolongs the difficulties associated with an immature cutaneous surface, such as increased water loss and thermal instability. Common neonatal skin variations are summarized in Table 14-5.

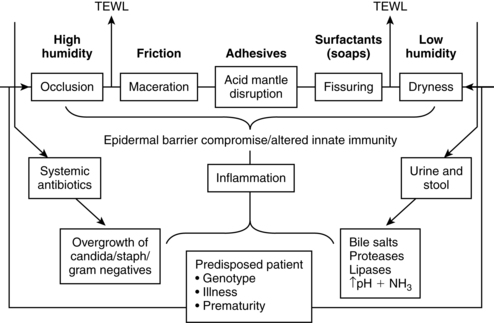

Once these initial stages are complete the skin takes on the adult protective functions by providing the needed environmental barrier. This development includes the discharge of water and electrolytes, an acid mantle, resorptive capacities, generalized pigmentation, and regulation of blood circulation and nerve supply. Factors affecting infant skin condition are summarized in Figure 14-3.

Barrier properties

The skin acts as a barrier to limit transepidermal water loss (TEWL), prevent absorption of drugs and other chemicals, and protect from invasion by pathogens.16,18 The barrier properties of the skin are located almost entirely in the stratum corneum. The stratum corneum is thinner in the infant than the adult and in the preterm compared to the term infant, and it increases with increasing gestational and postnatal age.18,51 Barrier maturation after birth is mediated by nuclear hormone receptors and their ligands (signal triggering and binding molecules).32

Components of barrier maturation include the thickness and organization of the epidermal layer. Organization of the epidermis has been compared to a brick wall with the corneocytes being the bricks and the lipid matrix the mortar.47,50 In the mature stratum corneum, the corneocytes are arranged in an organized pattern (like bricks) with a lamellar lipid matrix (the mortar). The corneocytes are interconnected by dermatomes to form a stable barrier. The lipid matrix acts as a barrier to transepidermal water loss. In the immature infant, the matrix is less well developed, with increased transepidermal water loss; the corneocytes are arranged in a more disorganized fashion and there are fewer intercellular connections between corneocytes.47,50

Epidermal thickness and functional maturation increase rapidly until about 24 weeks’ gestation.18 From that point until term, there is progressive thickening, which is seen in dermoepidermal undulations.100 In the term neonate the epidermis has marked regional variations in thickness, color, permeability, and surface chemical composition. As skin matures, the thickness of the stratum corneum increases. In the term infant this is a relatively well-developed barrier that may be 10 to 20 layers thick, as in the adult. However, in the preterm infant (especially those younger than 30 weeks’ gestation), the barrier is immature and may be only two to three layers thick. In infants younger than 24 gestational weeks, the stratum corneum is minimal.32,107,116

Skin hydration decreases immediately after birth, then increases as the stratum corneum adapts to the extrauterine environment.116 Stratum corneum hydration is lower in infants of less than 30 weeks’ gestation, related in part to incomplete development of the vernix caseosa (see Vernix Caseosa).32,116 Stratum corneum hydration is higher in vernix covered areas. Extremely low–birth weight infants may exhibit an abnormal pattern of skin desquamation after several weeks of extrauterine life due to hyperproliferation of the stratum corneum.114

For both the term and preterm infant, consequences of barrier immaturity include increased permeability and increased TEWL. Each of these properties is a function of gestational and postnatal age. The thinness of the barrier layer leaves the preterm neonate with an increased transepidermal loss, an increased skin permeability to chemical substances and microbes, and a decreased ability to withstand mechanical forces of friction.100 Rapid barrier maturation occurs over the first 10 to 14 days after birth in the term infant and 2 to 4 weeks in the preterm infant. Initial barrier maturation may take up to 8 weeks in the infant born at 25 to 27 weeks’ gestational age, or until the infant reaches a postmenstrual age of 30 to 32 weeks.56 Initial barrier maturation is mediated by exposure to the extrauterine environment. For example, an infant of 32 weeks’ gestational age who is 2 weeks old has had significant epidermal development in the first 2 weeks of postnatal life. This infant may be better able to cope with the extrauterine environment in terms of integumentary system function than a newly delivered term infant.43,76,100 However in all infants barrier maturation is not completed during the neonatal period, but is an ongoing process throughout infancy.9,82,106,114

Permeability

Skin permeability correlates with gestational age in the first few weeks of life. With decreasing gestational age, there is increasing permeability. Other factors increasing permeability are skin disease and injury.16,100 Thus even though the newborn’s skin may appear structurally similar to adult skin, it is more permeable to substances applied to the skin (e.g., drugs, chemicals) and more vulnerable to water fluxes. For example, antiseptics such as povidone-iodine, hexachlorophene, and isopropyl alcohol applied to an infant’s skin are absorbed to a much greater extent than in adults.16,100

Protective mechanisms

Although there are many immaturities in the cutaneous system, the accelerated maturation with birth (along with the pH of the infant’s skin) results in a protective barrier to the environment as long as the skin stays intact. Natural moisturizing factors (NMFs) in the stratum corneum act as skin lubricants and humectants to help the skin retain moisture.82 NMFs contain amino acids and their derivatives, organic acids, sugars, and ions. NMFs are lower in infants and altered with skin disorders and environmental factors.82,107

An acid skin surface with a pH lower than 5.0 enhances bacteriologic, chemical, and mechanical resistance and is needed for barrier maturation, repair, integrity, cohesion, and growth.32,67,114 The acid mantle is formed from the uppermost layer of the epidermis, sweat, superficial fat, sebum, metabolic by-products of keratinization, and external substances (e.g., amniotic fluid, microorganisms). The acid mantle can be disrupted by bathing and by the use of soaps and other topical agents.67

Skin pH increases immediately after birth, from the fetal pH of 5.5 to 6, and then decreases over the first week to a pH of 5.0 to 5.5.18,32,51 Skin pH reaches adult values by 3 to 4 weeks, although in some infants this may occur earlier or later.18 The mechanism for this change remains unclear but may be due to changes in the composition of the surface lipids and the activity of the eccrine glands.29 Vernix-covered areas have a more acidic pH than other areas in term infants.32 The acid mantle forms more slowly in preterm infants, especially those weighing less than 1000 g.33 Fox and colleagues reported that the skin pH in preterm infants (24 to 34 weeks’ gestational age) increased to a mean of 6 on the first day after birth and then fell to 5.4 by 1 week and to 5 by 1 month.33

Immediately following delivery, microbial colonization also begins. These bacteria grow in a state of equilibrium, providing protection against invading pathogenic organisms. Surface biomarkers of epidermal innate immunity include structural proteins, albumin, both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and antigen processing cells.79 Skin colonization after birth is discussed in Chapter 13.

Transepidermal water loss

Newborn skin has both greater water content and higher TEWL compared to adult skin.106 TEWL decreases rapidly after birth in term infants but more slowly in preterm infants and is inversely related to gestational age. Due to the thinner stratum corneum, higher water content, and increased permeability of the skin in preterm infants, TEWL is greatly increased, especially in the first 2 to 3 weeks after birth, and remains higher than term infants for up to a month or more.16,79 In infants less than 28 weeks’ gestational age, there is a 10- to 15-fold increase in TEWL.105 TEWL in infants less than 30 weeks’ gestational age may exceed resting heat loss production.99 As a result, fluid losses equivalent to 30% of their total body weight can occur. Even by 4 weeks post birth, TEWL in immature infants is still twice that of term infants.105 TEWL in infants older than 34 weeks’ gestational age approaches that of term infants. Other factors that increase TEWL in very low–birth weight (VLBW) infants are their larger surface area in relation to body weight and increased blood supply that is closer to the skin surface.

These water losses can have a significant effect on fluid balance and the management and treatment of both preterm and term neonates (see Chapter 11). This may be compounded by environmental (e.g., radiant warmers) and therapeutic (e.g., phototherapy) modalities (see Chapters 18 and 20). An increase in caloric needs due to the excessive TEWL may account for up to 20% of energy expenditure of infants younger than 30 weeks’ gestational age. Excess TEWL increases the risk of dehydration, intraventricular hemorrhage, hyperosmolar hypernatremia, and thermal instability due to evaporative heat loss.

The degree of TEWL is dependent upon the hydration of the stratum corneum, the skin surface temperature, ambient relative humidity, and the neural capability for control of sweating. Factors that may contribute to these losses include basal metabolic rate, body temperature, activity, use of radiant warmers, and conventional phototherapy.32,41,45 Term infants show little regional differences in TEWL, except for increased losses from the palms and soles secondary to sweating. TEWL in preterm infants is lowest on the forehead, cheeks, palms, and soles—areas where keratinization occurs early. These infants also do not sweat. TEWL is 50% higher in the abdomen of these infants and higher with warm (versus cool) skin, increased ambient temperature, radiant heating, or skin damage.16 Reduction of TEWL losses can be achieved through the use of thermal or plastic blankets or polyethylene skin wraps (see Chapter 20).103

Thermal environment

Heat exchange between infant skin and the environment is dependent on the thermal gradient between the body surface and environment. Studies have found minimal oxygen consumption when the body surface and environmental temperature gradient does not exceed 1.5° C (2.5° F). Use of incubators, radiant warmers, and phototherapy modifies the environment, either reducing or accelerating oxygen consumption. The rate of thermal exchange between infant and environment is dependent upon relative humidity, wind velocity, radiant surfaces, and ambient air temperatures. In neonates, 50% to 75% of heat loss occurs through radiation and is therefore dependent upon both ambient (incubator) and environmental (room) temperature (see Chapter 20). Higher humidity underneath diapers may down-regulate barrier competence in that area, increasing the risk of diaper dermatitis.32

Phototherapy (see Chapter 18) is an added radiant heat source. Infants receiving phototherapy have increased insensible water loss (IWL), respiratory rate, peripheral blood flow, and heel skin temperature. Absorption of infrared light waves increases kinetic energy, producing a degradation of the radiant energy to heat and leading to these clinical changes. The increased IWL is a compensatory mechanism to dissipate heat through hyperpnea and peripheral vasodilation. Careful temperature control can reduce some of these effects.

TEWL and heat loss via the skin are intimately linked (increased environmental temperature increases TEWL). Sweating is an important mechanism for heat regulation when thermal stress occurs and is a source of IWL.35 However, the ability to sweat in response to thermal or emotional stressors is dependent upon gestational and postnatal age.43

Infants of 36 weeks’ gestational age or older are able to generate sweat with a thermal stimulus, but generally require a greater stimulus than an adult.21 Term infants demonstrate emotional (palmar or plantar) sweating with an abrupt increase in palmoplantar sweating with exposure to a painful stimulus by the third day.43,49,50,100 The onset of sweating is delayed in preterm infants more than 28 weeks’ gestation; sweating is minimal or nonexistent in infants less than 28 weeks’ gestation, due to inadequate sweat gland development.100 Infants of 28 weeks’ gestation will sweat in response to a thermal challenge by 2 weeks post birth.100 These infants will have mild background palmar sweating with arousal but do not have the abrupt increase seen in term infants.100 Emotional sweating is weak or absent in preterm infants and develops from 36 weeks postmenstrual age.32

Sweating appears first on the forehead, and that may be the only place where it does occur, and then on the chest and upper arms.32 Gestational age and the number of sites where sweating is found during the first week of life are correlated.43,50 After that period, this correlation disappears. The amount of water loss varies with the state of arousal, the site of sweating, and the ambient and body temperatures, with the highest loss occurring from the forehead and then from the chest and the upper arms.43,50

Although the density of sweat glands is greatest at birth, many glands are inactive; adult function is not achieved until 2 to 3 years of age.19,50 The ability to respond to thermal stress matures between 21 and 33 days in more mature preterm infants and by 5 days in term infants. The actual water loss due to perspiration in the term infant is low, and although the preterm infant has greater losses, most are due not to perspiration but to TEWL.

Maturation of the sweat response may be a function of gland development (anatomic and functional) or maturation of the nervous system. In the fetus at 28 weeks the full complement of sweat glands is in place, many having formed lumina. The cholinergic fibers of the sympathetic nervous system are also in place. Chemical maturation, however, has not occurred, contributing to the absence of the sweat response in these infants.43

Cohesion between epidermis and dermis

Increased fluid losses may occur due to stripping of the stratum corneum through the repeated removal of tape. This problem is due to decreased cohesion between the epidermis and dermis. The epidermis firmly adheres to the underlying dermis in the adult at the dermoepidermal junction. The basal layer is anchored to the basement membrane by hemidesmosomes, anchoring filaments, and fibers that protrude from the undersurface of the basal cells. The undulations encountered in its structure enhance resistance to shearing stress at the junction.105

The skin of the preterm infant has decreased anchoring structures, higher water content, and widely spaced collagen fiber bundles in the dermis. This structural liability makes their skin integrity fragile and more susceptible to trauma from shearing and frictional or adhesive forces.19,67 For the preterm infant, cutaneous injury may occur with very little manipulation. The bond between the epidermis and the adhesive may be stronger than the bond between the infant’s epidermis and dermis.71 Denuded and damaged skin increases TEWL and may be a site of entry for bacterial infection until healing occurs. Extreme care when applying and removing tape or monitoring devices is therefore warranted, especially in the VLBW infant.

Collagen and elastin instability

Lack of connective tissue can result in increased trauma to the cutaneous layers in the VLBW infant. In addition, decreased collagen and elastic fibers may contribute to edema formation in the dermal layer, with concomitant increases in fluid loss due to increased fluid availability. This tendency toward water fixation decreases with increasing gestational age as collagen stability increases. Heat loss may be enhanced and thermal stability jeopardized due to the decreased insulative capabilities of the fibrous elements of the dermal layer.71

Cutaneous blood flow

The skin microcirculation is important in temperature maintenance, fluid balance regulation, tissue nutrition, and oxygen supply.32 The skin microvascular architecture is poorly developed and disorganized at birth with a horizontal dense plexus.19,32 Capillary loops are seen only in nailbeds, palms, and soles until after the first 2 weeks and not seen in all areas until 14 to 17 weeks after birth.32 Decreased skin capillary density is reported in some studies.84 Significant changes in blood vessel diameter are not noted until after the first month.60 During the first year the adult structure forms and vasomotor tone control is refined. Vasomotor tone is achieved through a complex series of nervous and chemical control mechanisms. These involve the sympathetic nervous system, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, and histamine. Other possible chemical influences include serotonin, vasoactive polypeptides, corticosteroids, and prostaglandins. VLBW preterm infants have immature vasomotor control even with low temperatures (see Chapter 20).32,58

Clinical implications for neonatal care

Clinical implications for the neonate due to the limitations of the integumentary system include skin care, absorption of substances through the skin, the use of adhesives, and thermal stability. Thermal stability and evaporative water loss are discussed in Chapter 20. The Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses/National Association of Neonatal Nurses Skin Care Guidelines are based on research evidence and expert opinion and provide guidance for skin assessment, bathing, cord care, reducing transepidermal water loss (TEWL), use of adhesives and emollients, and care of skin breakdown, intravenous line infiltration, and diaper dermatitis.3,68,70

Bathing

There is little consensus about the frequency of bathing. The timing of the first bath is delayed until the infant’s temperature and condition are stabilized and is influenced by cultural and family preferences.9 Standard precautions should be used before and during the first bath to avoid heat loss. Investigators have reported that it takes an average of an hour for the infant to return to prebath temperature.75 Others have found that the timing of the first bath did not significantly affect temperature.6 Term infants do not need daily bathing. Bathing, versus cloth or sponge washing, has been reported to be less stressful with less TEWL heat loss and better maintenance of stratum corneum hydration, with no differences in infection or bacterial colonization rates.9,38

Frequent baths are not needed for VLBW infants. Less frequent bathing has not been associated with an increase in infection or other adverse effects.34,92 Bathing can be a stressful experience for VLBW infants, with alterations in blood pH, hypoxemia, respiratory distress, increased oxygen consumption, crying, and behavioral stress cues.64,88,109,121 Bathing may also alter skin barrier properties.

Soaps are not generally needed in infants because of the low output of their sebaceous glands. Washing infants with alkaline soap destroys the acid mantle by neutralizing the pH. For the term infant, it takes 1 hour for the pH to return to baseline; for preterm infants it takes even longer. Due to concerns about increased skin permeability to other solutions, warm water only is recommended for preterm infants younger than 32 weeks’ gestation.71

Mild neutral pH soaps should only be used if needed for highly soiled areas. Because of concerns about human immunodeficiency virus and other pathogens, some institutions use a dilute antiseptic solution for the initial bath for term infants. The efficacy of this procedure is not clear.71 The solution should be thoroughly rinsed off the infant’s skin. Both antiseptic soaps and plain water decrease skin colonization of the infant, but only for about 4 hours, by which time the skin has re-colonized.71 No differences in skin bacterial colonization have been found after bathing with warm water versus mild soap and water.25

Creams, emollients, and lotions are not recommended for routine use, although there is a lack of evidence to support this recommendation.117 Not only do these substances affect the acid mantle; they may also be absorbed percutaneously. The optimal skin condition for the neonate is dry and flaking, without cracks and fissures. If cracking does occur, a thin application of nonperfumed, preservative-free emollient can be used.

Umbilical cord care

Cord care practices are often embedded in institutional tradition. Practices range from no care to cleansing with triple dye (brilliant green, gentian violet, and proflavine hemisulfate), povidone-iodine, chlorhexidine, isopropyl alcohol, or antimicrobial ointments. There are few data on the most effective method.55,71,105

Aseptic cord care decreases cord bacterial colonization but not necessarily the risk of infection, and delays cord separation.4,30,55,78 The current trend in both developed and developing countries is toward dry cord care. The World Health Organization recommends dry cord care in developing countries with soap and water cleaning of visibly soiled cords.119 Developing countries have a high cord infection rate; however, few studies demonstrate that antiseptic cord care reduces this rate.78 A Cochrane review by Zupan and colleagues of 21 studies (with 8959 subjects primarily from developed countries) found no difference in infection rates between dry cord care, placebo, and antiseptic use and also found that the use of antiseptics prolonged the time to cord separation.122 Similar findings have been reported in preterm infants.30 Aseptic care has been associated with decreased maternal concerns about the cord.122 However, Zupan and colleagues also concluded that “there appears to be no good reason to stop use of antiseptics in situations where bacterial infection remains high.”122

Use of adhesives

The epidermis is pulled off when adhesives are removed and can strip up to 70% to 90% of the stratum corneum in immature infants. In adults it takes 10 adhesive removals to disrupt the skin barrier versus only one removal of plastic tape, pectin barrier, or adhesive tape to do so in the preterm infant.69 Lund and colleagues compared plastic tape, pectin barrier, and hydrophilic gel use in the first week after birth in infants born at 24 to 40 weeks’ gestation.69 They found that pectin barriers and plastic tape had the highest colorimeter and vaporimeter scores, suggesting greater epidermal injury with these products than with hydrophilic gels. Skin barrier function returned to baseline by 24 hours. Although gel adhesives seemed preferable, they did not adhere as well to the skin as other products and thus required more frequent replacement.69

Denuded areas are a potential source of infection; they are also uncomfortable and are areas of increased fluid loss. Use of transparent semipermeable occlusive dressings, water-activated gel electrodes, and minimal tape to secure monitoring equipment and intravenous lines may reduce injury. Transparent dressings are impermeable to water and bacteria while also providing protection to abrasions and skin irritation. These dressings can also be used to cover line insertion sites or incision sites from invasive procedures. The advantages of this type of dressing include providing an optimal moist environment for healing, allowing serous exudate to form over the wound, facilitating migration of new cells across the wound area, and preventing cellular dehydration.46