The holistic approach ultrasound concept and the role of the critical care ultrasound laboratory

Overview

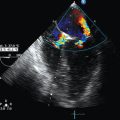

The approaches to examination of patients by clinical providers has evolved with the growth of medical knowledge and expectations of quality care. Though still primarily relying on their senses, physicians have been adding basic equipment (e.g., scale, stethoscope) and more complex devices (e.g., scopes, sphygmomanometer) to patient evaluation standards. In the intensive care unit (ICU), the diagnostic process is rather complex and continuous, and physical examination is deprived of several basic elements, such as pain assessment and general patient cooperation. Therefore, intensivists tend to rely on adjunctive diagnostic tools. The addition of critical care ultrasound (CCU) to the patient examination arsenal has been a major development during the last decade. The method fits naturally in the logic of the initial assessment process and, because of its repeatability, also in the continuous monitoring of these highly variable patients. As a generous source of real-time information, CCU shares a pedestal only with the physical examination itself.1,2

One overarching and powerful measure capable of tipping the balance toward accelerated maturation and phasing in of CCU is the development and promotion of a high-level, conceptually strong, and realistic approach. This chapter does that by further analyzing the holistic approach (HOLA) concept of CCU imaging that was introduced in Chapter 1. The HOLA concept defines CCU as part of the patient examination by a clinician to visualize all or any parts of the body, tissues, organs, and systems in their live, anatomically and functionally interconnected state and in the context of the whole patient’s clinical circumstances. The term “holistic” in the HOLA acronym is used in its original meaning in ancient Greek: to emphasize the importance of the whole and the interdependence of its parts. The term and the acronym must not be confused with “holistic medicine,” which has a different patient population, scope, and methodology. The authors of this chapter define the following overarching principles that should drive implementation of a HOLA-based CCU model in the ICU:

1. CCU is applicable in a “head-to-toe” fashion to follow and augment the process of physical examination and has an instantaneous effect on patient management.

2. Although specific CCU techniques deal with particular anatomic or pathologic entities, any tissue in any location in the body is subject to generic scanning.

3. A basic battery (profile) of CCU techniques can be adopted as a standard component of the bedside evaluation of every ICU patient.

4. Specialized batteries of CCU techniques can be implemented to best address the needs in specific clinical situations or patient categories.

5. Either CCU techniques or generic scanning should be categorized into basic and consultant levels. Basic techniques are performed by ICU team members. Consultant-level examinations that require radiology, cardiology, or other specialized expertise are supported by other teams external to the ICU but constitute a part of the overall imaging strategy in the ICU.

6. System- and facility-level acceptance is necessary for an appropriately planned and executed implementation process to gradually upgrade the conventional ICU to a “HOLA-capable” and, ultimately, an operational “HOLA-certified” status.

7. The ultimate stage of HOLA implementation is a full-fledged CCU laboratory with advanced equipment; clinical procedure support; archival, training, and broad quality assurance functions; and established interfaces with other hospital services and personnel.

Scope of critical care ultrasound

The scope of CCU is not to replace comprehensive sonography. CCU does not substitute for “radiologic” sonography, very much like Foley catheter placement does not make the urology service irrelevant; CCU replaces only studies that are largely futile in their solely retrospective significance. CCU performed by intensivists or other members of the ICU team augments the physical examination and has an instant effect on patient management. Moreover, it aids in dynamic monitoring of the constantly changing clinical status of ICU patients because of its bedside availability and repeatability. This dynamic monitoring capability is a distinct CCU feature that radiology routines can never adopt (e.g., recognize interstitial pulmonary edema and assess the effect of diuresis every 10 minutes). Most CCU techniques promise better outcomes only if used within the clinically driven time frame. Typically, still image–based, technician-performed studies are associated with delayed radiologist interpretation and serve different purposes.

The HOLA concept of critical care ultrasound imaging

The HOLA concept of CCU imaging was introduced in Chapter 1. This textbook in its entirety is, in essence, a detailed description of HOLA. In all fairness, adoption of HOLA is a major, understandably difficult conversion of a physician’s mindset and attitude toward changing the established routine of clinical practice. It takes effort to reconsider the notion that scanning is a prerogative of equipment-savvy technicians and image interpretation is a separate “darkroom magic” by radiologists. Such conversion requires realization and acceptance of the unity and synchrony of scanning and interpretation when performed by a clinician to see or rule out pathologies in real-time by using somewhat unconventional techniques and implementing complex monitoring protocols.3

From the facility perspective, acceptance of HOLA means that all known specialized diagnostic, monitoring, and procedure support CCU techniques are either operationally available or awaiting implementation, and moreover, every part of the human body is a potential target of generic scanning. In a short diversion, let us parse the generic scanning principle. Besides the special techniques that are usually based on published evidence, HOLA includes generic scanning based on recognition of tissues and organs by the physician. After specific training and initial practice, the real-time gray-scale image on the screen is correctly perceived as a live cross section underneath the transducer. Once physicians start recognizing the live anatomy on the screen, their medical knowledge becomes a strong quality assurance mechanism. The HOLA concept perceives generic anatomic assessment by CCU as another visual source of structural information from deeper tissues underneath the skin that are hidden from human vision and other senses. Surely, excellent knowledge of normal and pathologic anatomy is an essential prerequisite for successful interpretation of such information. Diagnostic dilemmas occur daily in the ICU, and expert consultation is necessary on many occasions. For example, echocardiography requires expert input to correctly assess anomalies that an intensivist cannot adequately clarify. The recent implementation of advanced echocardiographic techniques such as tissue Doppler and three-dimensional imaging into routine practice further underlines the importance of such input. Other techniques (e.g., abdominal or vascular ultrasound) may require additional review or a second opinion when the initial assessment is inconclusive. The introduction of invasive techniques such as intravascular and endobronchial ultrasound suggests the creation of on-site suites technically capable of supporting these applications. Moreover, new methods such as ultrasound molecular imaging and image-guided interventional procedures will continue their growth. Experimental studies targeting pathologic processes with contrast-enhanced ultrasound, such as angiogenesis, inflammation, thrombi, and plaque formation, have shown promising results and require special expertise and conditions.4–8 Notably, therapeutic agents can be attached to the particles of contrast agents to enhance drug delivery and effect (e.g., continuous transcranial Doppler was suggested to augment tissue plasminogen activator–induced arterial recanalization in stroke).8,9 Future studies are needed to validate the safety profiles, as well as the diagnostic and therapeutic indications, of the aforementioned and other highly specialized techniques. Assimilation of all established and realistically anticipated ultrasound techniques into the HOLA implementation goals appears to be an essential step-up for ICU services that will remain competitive for a reasonable number of years.

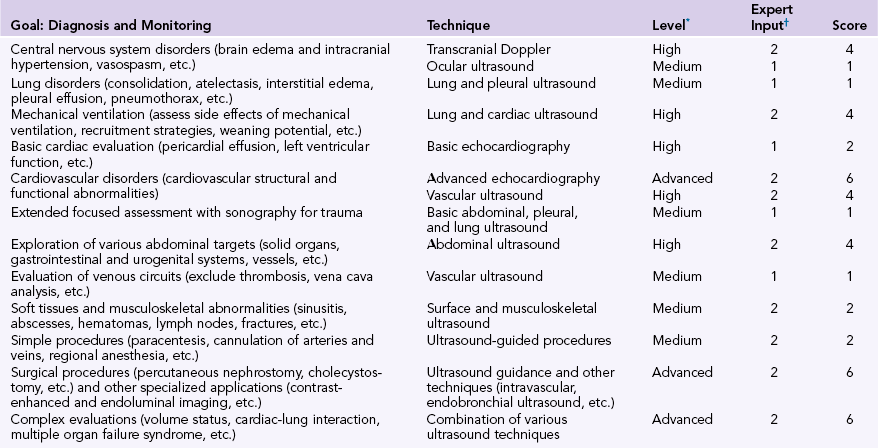

The HOLA concept and the set of overarching principles for its implementation outlined in the beginning of this chapter foresee basic and specific batteries of CCU techniques and generic scanning areas. Even though these batteries will probably differ between facilities and evolve in time, we suggest a number of illustrative examples (Table 57-1). Analyzing all goal-directed HOLA examination profiles is beyond our scope. Mastery of all techniques by the ICU team requires considerable education, training, and experience. Limitations do exist regarding the applicability of several CCU techniques, as analyzed in detail throughout this edition.

TABLE 57-1

Goal-Directed HOLA Critical Care Ultrasound Examination Profiles

*Level of expertise required to perform the examination (on a semiquantitative scale: basic = 0, medium = 1, high = 2, advanced = 3).

†Concomitant evaluation with other imaging, clinical, and laboratory data is necessary with all applied ultrasound techniques. The need for expert input to interpret the results of examinations is designated as 1 for unnecessary and 2 for necessary (or technique performed mainly by experts). The score (score = level of expertise × expert input) reflects the applicability of methods, with scores higher than 4 requiring extensive training and being more technically difficult; the opposite is true for methods with scores lower than 4. Scales were subjectively adjusted to comply with clinical notions and practices in Europe and the United States, as well as with the published literature.1,2

Physician education, training, and competence

In 2001 the American College of Emergency Physicians issued guidelines that defined the use of emergency ultrasound. Indications recommended for emergency ultrasound were trauma, pregnancy, emergency echocardiography, abdominal aorta imaging, and biliary, renal, and procedural ultrasound. The guideline was updated in 2008 to include new core applications such as ultrasound for deep venous thrombosis, soft tissue and musculoskeletal imaging, and thoracic and ocular imaging.10,11 Recently, the American College of Chest Physicians and La Société de Réanimation de Langue Française published their recommendations after a consensus meeting to define the use of ultrasound in the ICU. This consensus suggested that all intensivists should achieve competency in basic CCU techniques such as pleural, lung, abdominal, diagnostic, and procedural vascular ultrasound and basic critical care echocardiography.12 Notwithstanding the existence of recommendations as a basis for the future training of intensivists in ultrasound techniques, there is still a significant gap in ultrasound education, training, and accreditation. We wish to underline, however, that a tactical approach to CCU implementation based on a solid HOLA concept is a high-level demand that should no longer be overlooked by health authorities at all levels.

With adoption of the HOLA concept of ultrasound imaging by an ICU facility, ultrasound machines are placed in each unit (one machine for every two beds at the bedside) for use by all intensivists and for all patients. In such a setting, implementation of all known CCU techniques is significantly enabled. However, the array of special CCU techniques available depends on the combined CCU knowledge and experience of the intensivists present on a given shift. Moreover, thorough review of ambiguous results may require an expert such as a cardiologist or a radiologist (see Table 57-1). As in other ultrasound settings, CCU remains highly operator dependent, and the level of competency varies among operators and depends on training programs, background, and experience. In most European countries and in the United States, educational programs are gradually being introduced with specific requirements for various levels of competency in ultrasound applications.1,2 However, additional programs are clearly required to meet the growing demand for CCU education and training in most countries around the globe.

The critical care ultrasound laboratory

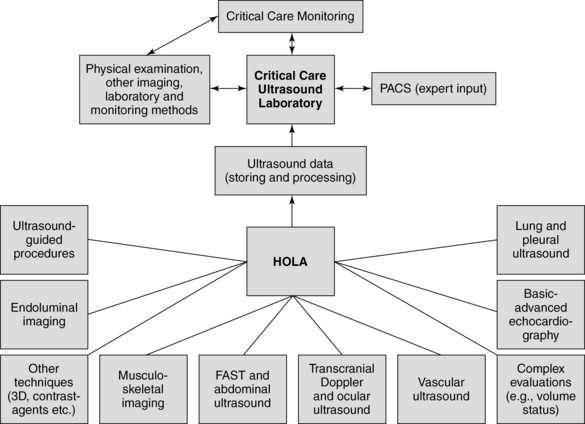

These considerations have led to a search for mechanisms to integrate CCU data and optimize the application of both diagnostic and procedural ultrasound. Hence, the idea of a CCU laboratory (CCUL) was formulated as a rational consequence of the suggested ultrasound model using a HOLA concept (Figure 57-1). A CCUL is, first of all, a data capture and archival capability unit within the ICU that uses in-hospital servers and can therefore be integrated into the well-established picture archiving and communication system (PACS). Application of a PACS minimizes consultation responding time and facilitates image interpretation and quality control (Chapter 56). Moreover, the growing availability of telemedicine options further enhances the expert consultation potential. Notably, in facilities with existing electronic medical record systems, the CCU imaging data could be integrated with other clinical, imaging, and laboratory data in the same platform or on the distributed network. Advocates of simple and stand-alone use of ultrasound may consider this centralized archival concept complicated and redundant. As the HOLA ultrasound concept is adopted and implemented, use of CCU and its effects on patient outcomes grow dramatically, and thus it becomes necessary to keep the imaging data well organized and functional as part of an overall approach to patient management. Another important feature of a CCUL is an actual physical suite within the unit that includes a central station with optimal features for specialized procedures such as relatively invasive diagnostics and ultrasound-guided interventions on a cart-based full-featured machine.

Figure 57-1 Diagram illustrating the capture of ultrasound data and archival capability of a full-fledged critical care ultrasound laboratory (CCUL) being integrated into intensive care unit (ICU) diagnostic and management logistics.

The operational cost of a CCUL should be properly evaluated, but no studies are available at this time to offer reference estimates. In view of the availability of portable ultrasound devices, along with the rapidly spreading integration of PACSs into hospital practice, we speculate that this cost may in fact be reasonable. Intensivists could enrich their knowledge and experience by continuous interaction with experts, and the training capabilities and benefits for residents, medical students, and operators are endless. Research activities could be strengthened and interactive clinical practice would flourish.

In the second half of the 20th century there was a general public notion that everything is achievable through technology. This notion remains very strong in modern hospital settings. However, technology should serve and not guide and usurp medical practice, which should be driven by opportunities to improve the standard of care. In that sense, advances in critical care patient management and ICU organization are steps in the right direction, and ultrasound technology has a great potential to support such developments. The primary anticipated benefits of adopting the HOLA concept of CCU imaging are improvement in patient care and outcomes and ICU bed efficiency. Secondary benefits are also numerous and spread beyond the hospital setting since many CCU solutions could be applicable to emergency fields and environments with limited resources. We highlighted in Chapter 50 the perspective of a very unique medical field, space medicine, as a user of yet another “flavor” of ultrasound diagnostics that combines many features of HOLA ultrasound imaging with telemedicine as it seeks new options to optimize safeguarding of the health of crew members during long-duration space missions.13

Pearls and highlights

• HOLA is a concept that relies on the universality and hands-on nature of ultrasound imaging and expects ultrasound to become a part of the nominal evaluation of every ICU patient, along with other physical examination components; it has an instant effect on patient management.

• A full-fledged CCUL may optimize the implementation and application of HOLA CCU and facilitate regular input by experts, maintain the equipment park, and ensure staff training and quality control.

• Cost-efficiency, credentialing, accreditation, requirements, and regulation issues should be addressed to ensure safe and effective function of a CCUL.

References

1. Price, S, Via, G, Sloth, E, et al, Echocardiography practice, training and accreditation in the intensive care: document for the World Interactive Network Focused on Critical Ultrasound (WINFOCUS). Cardiovasc Ultrasoun. 2008; 6:49.

2. Mayo, PH, Beaulieu, Y, Doelken, P, et al. American College of Chest Physicians/La Société de Réanimation de Langue Françoise statement on competence in critical care ultrasonography. Chest. 2009; 135:1050–1060.

3. Lichtenstein, D, Karakitsos, D. Integrating lung ultrasound in the hemodynamic evaluation of acute circulatory failure (the fluid administration limited by lung sonography protocol). J Crit Care. 2012; 27(5):e11–e29.

4. Voigt, JU. Ultrasound molecular imaging,. Methods. 2009; 48:92–97.

5. Lindner, JR. Contrast ultrasound molecular imaging of inflammation in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2009; 84:182–189.

6. Lerman, A, Zeiher, AM, Endothelial function: cardiac events. Circulatio. 2005; 111:363–366.

7. Alonso, A, Della Martina, A, Stroick, M, et al. Molecular imaging of human thrombus with novel abciximab immunobubbles and ultrasound. Stroke. 2007; 38:1508–1514.

8. Hernot, S, Klibanov, AL. Microbubbles in ultrasound-triggered drug and gene delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008; 60:1153–1166.

9. Alexandrov, AV, Molina, CA, Grotta, JC, et al. Ultrasound-enhanced systemic thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2004; 351(21):2170–2178.

10. American College of Emergency Physicians, Policy statement: ultrasound use for emergency patients, June 1991. Updated in 1997, 2001, and 2008. as Emergency Ultrasound Guidelines Available at www.acep.org, June 5, 2013 [Accessed on].

11. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Ultrasound Position Statement, 1991. Accessed www.saem.org, June 5, 2013. [Available at].

12. Cholley, BP, Mayo, PH, Poelaert, J, et al, for the Expert Round Table on Ultrasound in ICU: International expert statement on training standards for critical care ultrasonography. Intensive Care Me. 2011; 37:1077–1083.

13. Advanced diagnostic ultrasound in microgravity (ADUM). Available at www.Nasa.gov, October 10, 2013. [Accessed].