CHAPTER 5 The history and evolution of cataract surgery

The origins of cataract surgery

The father of Indian surgery Sushruta practiced during the 5th century BC, and dedicated a whole volume of work to ophthalmic disease, including treatment of cataract. He made what is taken to be the first description of extracapsular cataract surgery1, and described instruments specifically for this.

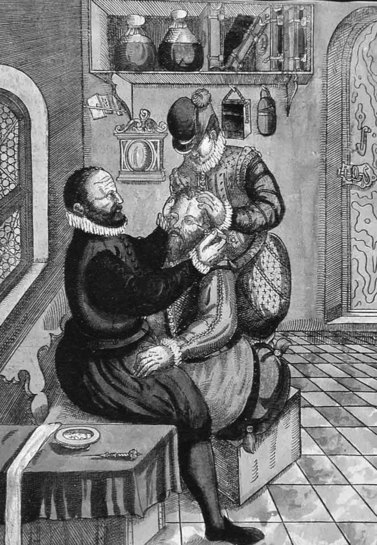

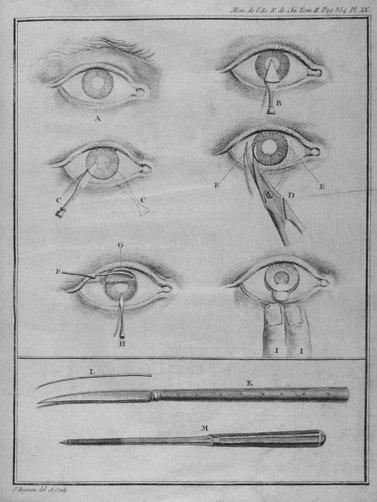

Couching continued throughout the Middle Ages in the Western world, with no apparent significant advance in understanding or development of technique. The famous surgeon Georg Bartisch (1535–1606) published his beautiful book Ophthalmodouleia in 15832, which was illustrated with woodcut prints, and described couching in some detail therein, mentioning not only the technique and instrumentation, but also some of the complications which might be expected (Fig. 5.1). In 1752 cataract surgery took a major step forward when the French ophthalmologist Jacques Daviel presented his paper ‘A new method of curing cataract by removing the lens’ to the French Royal Academy of surgery. His approach was via the inferior limbus, extending the wound symmetrically circumferentially on each side to somewhat greater than 180°. Intriguingly he had had very fine left and right cutting scissors constructed to accomplish this, as well as a curette and spatula, even at this early stage of development of his new approach (Fig. 5.2). His address is considered by many to be the defining moment in the history of modern cataract surgery.

The development of modern surgery

There can be little doubt, however, that the struggle which Harold Ridley (Fig. 5.3) fought to introduce lens implants to the world is as salutary as it is inspirational. Having recognized that splinters of Perspex from aeroplane cockpit canopies that had lodged in the eyes of fighter pilots did not extrude or inflame the eye, he developed the concept of implanting a lens made of high quality PMMA. His first operation took place in 1950 and was a triumph not only of his own vision and persistence, but of an early symbiosis between surgeon and manufacturers, which is now an assumed and integral part of surgical progress. Rayner Ltd. manufactured the lenses for Ridley from PMMA CQ (the suffix CQ standing for Clinical Quality), which was developed specifically for the purpose by ICI. Sadly his relationship with some of his colleagues was not as comfortable, and he was vilified by many who described his innovation as a potential ‘time bomb’. As his pupil Peter Choyce wrote in celebration of the 50th anniversary of Ridley’s pioneering procedure3 ‘I think even he was unprepared for the vicious nature of the onslaught to which he and his ideas were subjected’. Thanks to his conviction and drive however, and that of his supporters, Choyce amongst them, sense did eventually prevail, and allowed the rapid evolution of his concept into the sophisticated, but still developing technology that we recognize today.

Intracapsular and extracapsular surgery

It is perhaps testament to the prescience of Ridley that his original lens implantation was into the capsular bag as is the default in current practice, yet following his initial report there was a period of intraocular lens development when lenses were placed everywhere but in their natural position. In fairness, these deviations were for good reason, since the Ridley lens was prone to decentration and dislocation, and intracapsular surgery was widespread. In 1957 Barraquer described the use of alpha-chymotrypsin to facilitate intracapsular cataract surgery by causing zonular lysis, and in 1961 the Polish ophthalmologist Krawicz developed the technique of cryoextraction of the crystalline lens. Lens design was therefore concentrated on anterior chamber designs, Choyce and Ridley both being leading innovators in the field4. Lenses were ingeniously modified and refined to overcome the inherent problems of endothelial loss and resulting corneal failure associated with anterior chamber placement, and iris-supported lenses were promoted by some leading innovators. Binkhorst in particular pioneered a variety of lenses supported in this way, which, though less threatening to the corneal endothelium, had their own problems associated with dislocation or chafing of uveal tissue5. It is important to recall that ophthalmic viscoelastic devices (OVDs), formerly known as viscoelastics, were not in use at this time, and not until the 1980s did they become part of the armamentarium of the cataract surgeon6.

Phacoemulsification

Meanwhile, as the evolution of extracapsular surgery and posterior chamber lenses proceeded, Charles Kelman had been developing the use of ultrasonic phacoemulsification as a completely novel method of lens removal. The charming tale of Kelman’s epiphany moment, whilst his dentist worked on his teeth with an ultrasonic probe and he realized that this was the future of cataract surgery, is now legendary7, although he had already tried many other approaches by this stage. The development, as with most innovations, was much harder, and it took some years to refine the technology to a level that could be embraced by surgeons worldwide. Initially phacoemulsification was undertaken within the anterior chamber, with the obvious problems of collateral endothelial damage, but rapidly innovative surgeons took on Kelman’s new machine. Although he had first introduced it as early as 1967, it was not until the 1980s that the technique became widespread. Gimbel’s description of his ‘divide and conquer’ strategy for nuclear removal8 provided a platform for aspirant phaco surgeons to work from, and a basis for many subsequent eponymous techniques. The introduction of continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis9 opened the technique more widely still, by providing a much safer operating environment, and the security of lens centration which could subsequently lead to realistic attempts at multifocal lens design. A decade of exciting development in surgical technique saw the introduction of numerous innovations, including new wound constructions and placements, cortical cleaving hydrodissection, and many other nuclear strategies, such as ‘phaco-chop’.

Progress rarely occurs without new challenges appearing along the way, and the relatively sudden transition to phacoemulsification cataract surgery has certainly not been without difficulties. Quite apart from the generation of cataract surgeons who had to navigate such a paradigm shift in their surgical practice, modern surgery continues to demand the development of exacting and precise skills in those learning the technique. The high expectations of patients and pressures of the sheer numbers of trainees who need to learn cataract surgery in what is often a limited and inflexible time limit have generated ever greater requirements for teaching in a challenging environment. The ubiquity of local anesthesia has created a very different learning environment to that of the past, when surgery was much more commonly undertaken under either general anesthesia or deep sedation. The responses to such pressures, however, have in themselves been almost as innovative and revolutionary as the surgery they require to teach. In particular, the development of artificial environments for teaching, such as skills laboratories (Fig. 5.4) with either animal or prosthetic eyes, and more recently of computer based surgical simulators to train surgeons, have allowed great progress in surgical training, enhancing trainees’ learning experience, and patient safety10.

1 Kansupasa KB, Sassani JW. Sushruta the father of Indian surgery and ophthalmology. Doc Ophthalmol. 1997;93:159-167.

2 Blanchard D. Ophthalmodouleia: that is the service of the eye (Translation). Ostend, Belgium: J.P. Wayenborgh Press; 1996.

3 Choyce DP. 50th Anniversary of Ridley’s pioneering procedure. Lancet. 1999;354:53-69.

4 Apple DJ, Ram J, Foster A, et al. Cataract surgery with rigid and foldable posterior chamber IOLs, ECCE and phacoemulsification. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;Suppl. 1:S70-S99.

5 Binkhorst CD. Iris-clip and irido-capsular lens implants (pseudophakoi): personal techiniques of pseudophakia. Br J Ophthalmol. 1967;51:767-771.

6 Scholtz S. History of ophthalmic viscosurgical devices. Cataract Refract Surg Today Europe. 2007:27-29.

7 Kelman CD. Through my eyes: The story of a surgeon who dared to take on the medical world. New York: Crown Publishing; 1985.

8 Gimbel HV. Divide and conquer nucleofractis phacoemulsification: development and variations. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1991;17:281-291.

9 Neuhann T. Theorie und operationstechnik der kapsulorhexis. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1987;190:542-545.

10 Khalifa YM, Bogorad D, Gibson V, et al. Virtual reality in ophthalmology training. Surv Ophthalmol. 2006;51:259-273.